Albania's 'Sworn Virgins'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albanian Language Identification in Text

5 BSHN(UT)23/2017 ALBANIAN LANGUAGE IDENTIFICATION IN TEXT DOCUMENTS *KLESTI HOXHA.1, ARTUR BAXHAKU.2 1University of Tirana, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Department of Informatics 2University of Tirana, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Department of Mathematics email: [email protected] Abstract In this work we investigate the accuracy of standard and state-of-the-art language identification methods in identifying Albanian in written text documents. A dataset consisting of news articles written in Albanian has been constructed for this purpose. We noticed a considerable decrease of accuracy when using test documents that miss the Albanian alphabet letters “Ë” and “Ç” and created a custom training corpus that solved this problem by achieving an accuracy of more than 99%. Based on our experiments, the most performing language identification methods for Albanian use a naïve Bayes classifier and n-gram based classification features. Keywords: Language identification, text classification, natural language processing, Albanian language. Përmbledhje Në këtë punim shqyrtohet saktësia e disa metodave standarde dhe bashkëkohore në identifikimin e gjuhës shqipe në dokumente tekstuale. Për këtë qëllim është ndërtuar një bashkësi të dhënash testuese e cila përmban artikuj lajmesh të shkruara në shqip. Për tekstet shqipe që nuk përmbajnë gërmat “Ë” dhe “Ç” u vu re një zbritje e konsiderueshme e saktësisë së identifikimit të gjuhës. Për këtë arsye u krijua një korpus trajnues i posaçëm që e zgjidhi këtë problem duke arritur një saktësi prej më shumë se 99%. Bazuar në eksperimentet e kryera, metodat më të sakta për identifikimin e gjuhës shqipe përdorin një klasifikues “naive Bayes” dhe veçori klasifikuese të bazuara në n-grame. -

Ecosystem Profile Madagascar and Indian

ECOSYSTEM PROFILE MADAGASCAR AND INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS FINAL VERSION DECEMBER 2014 This version of the Ecosystem Profile, based on the draft approved by the Donor Council of CEPF was finalized in December 2014 to include clearer maps and correct minor errors in Chapter 12 and Annexes Page i Prepared by: Conservation International - Madagascar Under the supervision of: Pierre Carret (CEPF) With technical support from: Moore Center for Science and Oceans - Conservation International Missouri Botanical Garden And support from the Regional Advisory Committee Léon Rajaobelina, Conservation International - Madagascar Richard Hughes, WWF – Western Indian Ocean Edmond Roger, Université d‘Antananarivo, Département de Biologie et Ecologie Végétales Christopher Holmes, WCS – Wildlife Conservation Society Steve Goodman, Vahatra Will Turner, Moore Center for Science and Oceans, Conservation International Ali Mohamed Soilihi, Point focal du FEM, Comores Xavier Luc Duval, Point focal du FEM, Maurice Maurice Loustau-Lalanne, Point focal du FEM, Seychelles Edmée Ralalaharisoa, Point focal du FEM, Madagascar Vikash Tatayah, Mauritian Wildlife Foundation Nirmal Jivan Shah, Nature Seychelles Andry Ralamboson Andriamanga, Alliance Voahary Gasy Idaroussi Hamadi, CNDD- Comores Luc Gigord - Conservatoire botanique du Mascarin, Réunion Claude-Anne Gauthier, Muséum National d‘Histoire Naturelle, Paris Jean-Paul Gaudechoux, Commission de l‘Océan Indien Drafted by the Ecosystem Profiling Team: Pierre Carret (CEPF) Harison Rabarison, Nirhy Rabibisoa, Setra Andriamanaitra, -

AP ART HISTORY--Unit 5 Study Guide (Non Western Art Or Art Beyond the European Tradition) Ms

AP ART HISTORY--Unit 5 Study Guide (Non Western Art or Art Beyond the European Tradition) Ms. Kraft BUDDHISM Important Chronology in the Study of Buddhism Gautama Sakyamuni born ca. 567 BCE Buddhism germinates in the Ganges Valley ca. 487-275 BCE Reign of King Ashoka ca. 272-232 BCE First Indian Buddha image ca. 1-200 CE First known Chinese Buddha sculpture 338 CE First known So. China Buddha image 437 CE The Four Noble Truthsi 1. Life means suffering. Life is full of suffering, full of sickness and unhappiness. Although there are passing pleasures, they vanish in time. 2. The origin of suffering is attachment. People suffer for one simple reason: they desire things. It is greed and self-centeredness that bring about suffering. Desire is never satisfied. 3. The cessation of suffering is attainable. It is possible to end suffering if one is aware of his or her own desires and puts and end to them. This awareness will open the door to lasting peace. 4. The path to the cessation of suffering. By changing one’s thinking and behavior, a new awakening can be reached by following the Eightfold Path. Holy Eightfold Pathii The principles are • Right Understanding • Right Intention • Right Speech • Right Action • Right Livelihood • Right Effort • Right Awareness • Right Concentration Following the Eightfold Path will lead to Nirvana or salvation from the cycle of rebirth. Iconography of the Buddhaiii The image of the Buddha is distinguished in various different ways. The Buddha is usually shown in a stylized pose or asana. Also important are the 32 lakshanas or special bodily features or birthmarks. -

Major Geographic Qualities of South Asia

South Asia Chapter 8, Part 1: pages 402 - 417 Teacher Notes DEFINING THE REALM I. Major geographic qualities of South Asia - Well defined physiography – bordered by mountains, deserts, oceans - Rivers – The Ganges supports most of population for over 10,000 years - World’s 2nd largest population cluster on 3% land mass - Current birth rate will make it 1st in population in a decade - Low income economies, inadequate nutrition and poor health - British imprint is strong – see borders and culture - Monsoons, this cycle sustains life, to alter it would = disaster - Strong cultural regionalism, invading armies and cultures diversified the realm - Hindu, Buddhists, Islam – strong roots in region - India is biggest power in realm, but have trouble with neighbors - Kashmir – dangerous source of friction between 2 nuclear powers II. Defining the Realm Divided along arbitrary lines drawn by England Division occurred in 1947 and many lives were lost This region includes: Pakistan (East & West), India, Bangladesh (1971), Sri Lanka, Maldives Islands Language – English is lingua franca III. Physiographic Regions of South Asia After Russia left Afghanistan Islamic revivalism entered the region Enormous range of ecologies and environment – Himalayas, desert and tropics 1) Monsoons – annual rains that are critical to life in that part of the world 1 2) Regions: A. Northern Highlands – Himalayas, Bhutan, Afghanistan B. River Lowlands – Indus Valley in Pakistan, Ganges Valley in India, Bangladesh C. Southern Plateaus – throughout much of India, a rich -

Honor Crimes of Women in Albanian Society Boundary Discourses On

HONOR CRIMES OF WOMEN IN ALBANIAN SOCIETY BOUNDARY DISCOURSES ON “VIOLENT” CULTURE AND TRADITIONS By Armela Xhaho Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies Supervisor: Professor Andrea Krizsan Second Reader: Professor Eva Fodor CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2011 Abstract In this thesis, I explore perceptions of two generations of men on the phenomenon of honor crimes of women in Albanian society, by analyzing in particular discourses on cultural and regional boundaries in terms of factors that perpetuate crimes in the name of honor. I draw on the findings from 24 in depth interviews, respectively 17 interviews with two generations of men who have migrated from remote villages of northern and southern Albania into periphery areas of Tirana and 7 interviews with representatives of key institutional authorities working in the respective communities. The conclusions reached in this study based on the perceptions of two generations of men in Albania suggest that, the ongoing regional discourses on honor crimes of women in Albanian society are still articulated by the majority of informants in terms of “violent” and “backward” cultural traditions, by exonerating the perpetrators and blaming the northern culture for perpetuating such crimes. However, I argue that the narrow construction on cultural understanding of honor crimes of women fails to acknowledge the gendered aspect of violence against women as a universal problem of women’s human rights across different cultures. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to acknowledge my supervisor Professor Andrea Krizsan for all her advices and helpful comments during the whole period of thesis writing. -

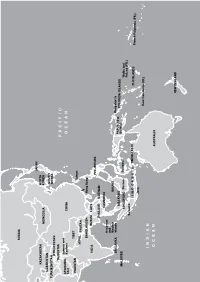

Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the Country

ARCTIC OCEAN RUSSIA JAPAN KAZAKHSTAN NORTH MONGOLIA KOREA UZBEKISTAN SOUTH TURKMENISTAN KOREA KYRGYZSTAN TAJIKISTAN PACIFIC Jammu and AFGHANIS- Kashmir CHINA TAN OCEAN PAKISTAN TIBET Taiwan NEPAL BHUTAN BANGLADESH Hong Kong INDIA BURMA LAOS PHILIPPINES THAILAND VIETNAM CAMBODIA Andaman and Nicobar BRUNEI SRI LANKA Islands Bougainville MALAYSIA PAPUA NEW SOLOMON ISLANDS MALDIVES GUINEA SINGAPORE Borneo Sulawesi Wallis and Futuna (FR.) Sumatra INDONESIA TIMOR-LESTE FIJI ISLANDS French Polynesia (FR.) Java New Caledonia (FR.) INDIAN OCEAN AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the country. However, this doctrine is opposed by nationalist groups, who interpret it as an attack on ethnic Kazakh identity, language and Central culture. Language policy is part of this debate. The Asia government has a long-term strategy to gradually increase the use of Kazakh language at the expense Matthew Naumann of Russian, the other official language, particularly in public settings. While use of Kazakh is steadily entral Asia was more peaceful in 2011, increasing in the public sector, Russian is still with no repeats of the large-scale widely used by Russians, other ethnic minorities C violence that occurred in Kyrgyzstan and many urban Kazakhs. Ninety-four per cent during the previous year. Nevertheless, minor- of the population speak Russian, while only 64 ity groups in the region continue to face various per cent speak Kazakh. In September, the Chair forms of discrimination. In Kazakhstan, new of the Kazakhstan Association of Teachers at laws have been introduced restricting the rights Russian-language Schools reportedly stated in of religious minorities. Kyrgyzstan has seen a a roundtable discussion that now 56 per cent continuation of harassment of ethnic Uzbeks in of schoolchildren study in Kazakh, 33 per cent the south of the country, and pressure over land in Russian, and the rest in smaller minority owned by minority ethnic groups. -

The Traditional Tower Houses of Kosovo and Albania - Origin, Development and Influences

University of Business and Technology in Kosovo UBT Knowledge Center UBT International Conference 2018 UBT International Conference Oct 27th, 3:15 PM - 4:45 PM The rT aditional Tower Houses of Kosovo and Albania -Origin, Development and Influences Caroline Jaeger-Klein Technische Universität Wien, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledgecenter.ubt-uni.net/conference Part of the Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Jaeger-Klein, Caroline, "The rT aditional Tower Houses of Kosovo and Albania -Origin, Development and Influences" (2018). UBT International Conference. 27. https://knowledgecenter.ubt-uni.net/conference/2018/all-events/27 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Publication and Journals at UBT Knowledge Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in UBT International Conference by an authorized administrator of UBT Knowledge Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Traditional Tower Houses of Kosovo and Albania - Origin, Development and Influences. Caroline Jaeger-Klein1 1 Vienna University of Technology, Department for History of Architecture and Building Archaeology, Karlsplatz 13/251; A-1040 Vienna, Austria [email protected] Abstract. Gheg-Albanians as well as Tosk-Albanians consider a distinct tower-house type of their traditional heritage. The closer look upon the structures in their geographical distribution from the Dukajin plains in nowadays Kosovo into the Dropull valley in Southern Albania provides a wide range of variations. Generally those structures served as impressive residential houses (banesa) for rich landlords, warlords, tax collectors and merchants performing a rural- urban lifestyle. Therefore, a sophisticated blend of the all-time defendable Albanian tower house (kulla), still existing quite intact in the western Kosovo plains, and the comfortable Turkish life- style influenced residence was developed during the long centuries of the Ottoman rule over Western Balkans. -

Albanian Migrant Women

Albanian migrant women Relation between migration and empowerment of women. The case-study of Albania A Bachelor Thesis Subject: Migration and the empowerment of women Title: Relation between migration and the empowerment of women. The case-study of Albania. Thesis supervisor: Dr. Bettina Bock Student: Liza Iessa Student ID: 870806532080 Date: 30 May 2014 City: Wageningen Institute: University of Wageningen Program: International Development Studies Abstract This is an explorative research of the determinants of migration for women who come from male dominant societies and migrate to more equal societies. The main theory used is the theory of the push and pull factor. The oppression of women in dominantly male societies is defined as a push factor. And opportunities for self-empowerment in more equal societies are defined as a pull factor. In Albania men are the ones who become the head of the household and only men are allowed to own any property. According to the Kanun any women that act in any way as a dishonourable person should be punished or even should pay with her blood. In male dominated societies, such as Albania, there a only few opportunities for women to climb the ladder in the labour market. It makes it very hard for women to provide for themselves and their families financially. Escape high levels of gender inequality is defined as an important reason for Albanian women to migrate. After the fall of the communist regime in the 90’s, the national borders opened up and migration from Albania has increased tremendously. Some women escape male dominant society by migrating to regions with relatively more equality in gender relations. -

|||GET||| Women Who Become Men Albanian Sworn Virgins 1St Edition

WOMEN WHO BECOME MEN ALBANIAN SWORN VIRGINS 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE A Young | 9781859733400 | | | | | Women Who Become Men: Albanian Sworn Virgins Tove rated it it was amazing Dec 06, Edith Durham, whose High Albania I read a while ago, goes into this in much more detail. Overall, an enjoyable read which I learnt a lot from - especially about wider Albanian society, which I wasn't necessarily expecting to from the book title. There are also establishments that they cannot enter. There is an image of the Madonna on the table and an apple core. For anyone who has even a very basic knowledge of this subject, this book is not helpful. I found especially interesting that economic concerns i. But I never wanted to marry. About Antonia Young. To a lesser extent, the practice exists, or has existed, in other parts of the western Balkans, including BosniaDalmatia CroatiaSerbia and Northern Macedonia. According to Marina Warnerthe sworn virgin's "true sex will never again, on pain Women Who Become Men Albanian Sworn Virgins 1st edition death, be alluded to either in her presence or out of it. But such rigid notions are overturned by certain women in remote regions of Albania who elect to 'become' men simply for the advantages that accrue to them as a result. Continue on UK site. I am never scared. Bibliography of works on wartime cross-dressing Rebecca Riots Women Who Become Men Albanian Sworn Virgins 1st edition Trousers as women's clothing Gender non-conformance Transgender. The reader-friendly style and the somewhat slightly sentimantal narrative leads the reader into a rather short and somewhat basic analysis of the "dress" of the sworn virgins. -

Gheg Albanians Belgium

UUPG Gheg Albanians in Belgium People Name Gheg Albanians Country Belgium Status Unengaged Unreached Population 177,000 Language Gheg Albanian Religion Islam Written Scripture Yes Oral Scripture Yes Jesus Film Yes Gospel Recordings Yes Christ Followers No Churches No "Therefore beseech the Lord of the harvest Workers Needed 3 to send out workers into His harvest." Workers Reported 0 Photo: Anonymous INTRODUCTION / HISTORY WHAT ARE THEIR BELIEFS? and represent His Kingdom on earth. (Mt The Albanians are believed to be Centuries ago, many Albanians were 6:9-10, Rom 12:2, 2 Cor 3:18) descendants of the Illyrians, who were the converted to Islam by the Ottoman Turks. original inhabitants of the western Balkan However, they practiced a type of "folk * Pray for every opposing spirit to give way Peninsula. In the sixth century, migrating Islam," which embraced occult practices to the liberating, life-giving gospel of the Slavs began to settle on Illyrian territory such as praying to the dead, seeking cures Lord Jesus Christ, the coming King. (James and pushed the Illyrians into what is for sickness, and praying for protection 4:7, 2 Cor 10:4-5, 1 Cor 15:58, Mt 18:18) present-day Albania. The Albanians are from spirits and curses. divided into two major groups, the Gheg SOURCES and the Tosk, according to which Albanian WHAT ARE THEIR NEEDS? https://goo.gl/Yav1QR dialect they speak. The two dialects differ The Albanians in Belgium need advanced https://goo.gl/sIQZIx slightly in vocabulary and pronunciation. In language skills and educational https://goo.gl/a0DBrb the 1950s it was decided that the Tosk opportunities so they can thrive in https://goo.gl/ugy3Hy dialect would be used in all Albanian Belgium’s highly advanced economy. -

Anthropology of Gender in Montenegro. an Introduction

Comp. Southeast Europ. Stud. 2021; 69(1): 5–18 In the Name of the Daughter. Anthropology of Gender in Montenegro Čarna Brković* In the Name of the Daughter – Anthropology of Gender in Montenegro. An Introduction https://doi.org/10.1515/soeu-2021-2013 Gender in Montenegro In 2012 international organizations warned that Montenegro is one of the world’s leaders in sex-selective abortion, with as a result significantly fewer births of babies recognized as girls.1 Initially, that piece of data seemed to attract little attention, but that changed after a few years. NGOs working on women’srightsorganizedcampaigns advocating against the practice of sex-selective abortion; German journalists came to Montenegro and reported on them; the Montenegrin national newspaper Pobjeda stopped publishing information on the genders of new-born children and began reporting births gender-neutrally instead. In dominant media and NGO discourses, sex- selective abortion was interpreted as the result of the patriarchal backwardness of the country, where sons were more valued and, therefore, more wanted than daughters. The collection of articles in front of you explores how to look beyond the balkanist discourse to understand abortion and other gendered practices in Montenegro.2 It articulates anthropological criticism of patriarchy, misogyny, and gender inequality in Montenegro without reiterating the common tropes about 1 United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) data reveal that Montenegro is one of the top eleven countries in the world for sex imbalance at birth; that is in the difference between the numbers of boys and girls. Cf. Christophe Z. Guilmoto, Sex Imbalances at Birth. Current Trends, Consequences and Policy Implications, UNFPA Asia and Pacific Regional Office, Bangkok 2012, 20. -

LRA2016 Hantman Essay.Pdf (117.3Kb)

Rachel Hantman June 10, 2015 Geography 431 Amy Piedalue For my creative piece, I created a “flipbook” demonstrating the transition Albanian women undergo when they become Albanian Sworn Virgins. Sworn Virgins are women who are primarily from Northern Albania and who, at a young age, take an oath of celibacy, and in doing so, societally transformed themselves into men. By taking this oath in front of twelve men, their celibacy allows them to avoid an arranged marriage (or the possibility of one), which transfers societal meaning onto them and they become men (Littlewood 45). As recognized males in their community, they are able to participate in the codified law as powerful beings with agency as opposed to powerless women lacking choices. This law that strongly influences their society is known as the Code of Lekë Dukagjini, or the Kanun, and it generates a highly patriarchal environment, “Patriarchy is assumed… marriage is ‘for the purpose of adding to the work force and increasing the number of children’… women are not involved in blood feuds… because a woman’s blood is not equal to a man’s… ‘A woman is a sack, made to endure’” (Post 53-54). With the Kanun’s lack of religious backing and affiliation, the choice to become a Sworn Virgin is then deeply rooted in Northern Albanian societal standards (Štulhofer and Sandfort 80). If a family lacks sons, if a familial male leader dies, or if a young girls wants a life of mobility, she may chose to take the oath as an act of self-empowerment and as a means to better her and/or her family’s position in society (Bilefsky).