Reappraising the Renaissance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Call Them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960S Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK

Why Call them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960s Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK Preface In response to the recent increased prominence of studies of "cult movies" in academic circles, this essay aims to question the critical usefulness of that term, indeed the very notion of "cult" as a way of talking about cultural practice in general. My intention is to inject a note of caution into that current discourse in Film Studies which valorizes and celebrates "cult movies" in particular, and "cult" in general, by arguing that "cult" is a negative symptom of, rather than a positive response to, the social, cultural, and cinematic conditions in which we live today. The essay consists of two parts: firstly, a general critique of recent "cult movies" criticism; and, secondly, a specific critique of the term "cult movies" as it is sometimes applied to 1960s American independent biker movies -- particularly films by Roger Corman such as The Wild Angels (1966) and The Trip (1967), by Richard Rush such as Hell's Angels on Wheels (1967), The Savage Seven, and Psych-Out (both 1968), and, most famously, Easy Rider (1969) directed by Dennis Hopper. Of course, no-one would want to suggest that it is not acceptable to be a "fan" of movies which have attracted the label "cult". But this essay begins from a position which assumes that the business of Film Studies should be to view films of all types as profoundly and positively "political", in the sense in which Fredric Jameson uses that adjective in his argument that all culture and every cultural object is most fruitfully and meaningfully understood as an articulation of the "political unconscious" of the social and historical context in which it originates, an understanding achieved through "the unmasking of cultural artifacts as socially symbolic acts" (Jameson, 1989: 20). -

Jessica Lange Regis Dialogue Formatted

Jessica Lange Regis Dialogue with Molly Haskell, 1997 Bruce Jenkins: Let me say that these dialogues have for the better part of this decade focused on that part of cinema devoted to narrative or dramatic filmmaking, and we've had evenings with actors, directors, cinematographers, and I would say really especially with those performers that we identify with the cutting edge of narrative filmmaking. In describing tonight's guest, Molly Haskell spoke of a creative artist who not only did a sizeable number of important projects but more importantly, did the projects that she herself wanted to see made. The same I think can be said about Molly Haskell. She began in the 1960s working in New York for the French Film Office at that point where the French New Wave needed a promoter and a writer and a translator. She eventually wrote the landmark book From Reverence to Rape on women in cinema from 1973 and republished in 1987, and did sizable stints as the film reviewer for Vogue magazine, The Village Voice, New York magazine, New York Observer, and more recently, for On the Issues. Her most recent book, Holding My Own in No Man's Land, contains her last two decades' worth of writing. I'm please to say it's in the Walker bookstore, as well. Our other guest tonight needs no introduction here in the Twin Cities nor in Cloquet, Minnesota, nor would I say anyplace in the world that motion pictures are watched and cherished. She's an internationally recognized star, but she's really a unique star. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Painting En Abyme: Tracing the Uses of Painting in New Hollywood Cinema

PAINTING EN ABYME: TRACING THE USES OF PAINTING IN NEW HOLLYWOOD CINEMA By MICHELLE LYNN RINARD Bachelor of Arts in Art History Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois 2010 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2015 PAINTING EN ABYME: TRACING THE USES OF PAINTING IN NEW HOLLYWOOD CINEMA Thesis Approved: Dr. Louise Siddons Thesis Adviser Dr. Jeff Menne Dr. Rebecca Brienen ii Name: MICHELLE L. RINARD Date of Degree: MAY 2015 Title of Study: PAINTING EN ABYME: TRACING THE USES OF PAINTING IN NEW HOLLYWOOD CINEMA Major Field: ART HISTORY Abstract: In the period of the New Hollywood in cinema, four directors created films that incorporated paintings and artworks within their scenes: Mike Nichols’ The Graduate (1967); John Frankenheimer’s Seconds (1966); Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971); and Paul Mazursky’s An Unmarried Woman (1978). In four close readings, I demonstrate that these filmmakers incorporated painting to contribute to the emotions and narrative, to reflect the institutional power or ideological positions of characters and organizations, and as cultural or anti-cultural capital. The incorporation of painting in film creates a mise en abyme, doubling the forms and meanings of art within the film medium. The use of painting in cinema in the period between 1966 and 1978 is characteristic of an artistic trend in New Hollywood filmmaking. Earlier uses of art in film were overwhelmingly narrative and diegetic, while in New Hollywood film it becomes a mode of editorializing and extra diegetic commentary. -

(XXXIX:9) Mel Brooks: BLAZING SADDLES (1974, 93M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

October 22, 2019 (XXXIX:9) Mel Brooks: BLAZING SADDLES (1974, 93m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Mel Brooks WRITING Mel Brooks, Norman Steinberg, Richard Pryor, and Alan Uger contributed to writing the screenplay from a story by Andrew Bergman, who also contributed to the screenplay. PRODUCER Michael Hertzberg MUSIC John Morris CINEMATOGRAPHY Joseph F. Biroc EDITING Danford B. Greene and John C. Howard The film was nominated for three Oscars, including Best Actress in a Supporting Role for Madeline Kahn, Best Film Editing for John C. Howard and Danford B. Greene, and for Best Music, Original Song, for John Morris and Mel Brooks, for the song "Blazing Saddles." In 2006, the National Film Preservation Board, USA, selected it for the National Film Registry. CAST Cleavon Little...Bart Gene Wilder...Jim Slim Pickens...Taggart Harvey Korman...Hedley Lamarr Madeline Kahn...Lili Von Shtupp Mel Brooks...Governor Lepetomane / Indian Chief Burton Gilliam...Lyle Alex Karras...Mongo David Huddleston...Olson Johnson Liam Dunn...Rev. Johnson Shows. With Buck Henry, he wrote the hit television comedy John Hillerman...Howard Johnson series Get Smart, which ran from 1965 to 1970. Brooks became George Furth...Van Johnson one of the most successful film directors of the 1970s, with Jack Starrett...Gabby Johnson (as Claude Ennis Starrett Jr.) many of his films being among the top 10 moneymakers of the Carol Arthur...Harriett Johnson year they were released. -

The Rice Thresher Volume 59, Number 14 Thursday

4> s New coach Conover speaks out on academics, athletics by GARY RACHLIN things that I'd like to get done and how getting a "1" for the program . breakfast entirely. As far as lunch, I'm Last Saturday, President Hackerman will they affect Rice University. So I'm Thresher: Do you have any desire for going to leave it up to the football announced that Rice's new head coach going to be very cautious about what I an athletic dorm at Rice? team. During the season and spring- is A1 Conover and the new athletic di- do. Conover: An athletic dormitory? At practice we will have training table for rector is "Red" Bale. Monday I had an Thresher: What sort of things do you Rice? Not at Rice University. I wouldn't lunch, but for the rest oft the time, the interview with Conover. Excerpts follow: need for a successful football program even consider that. That's absurd. decision will be left to the team. at Rice? Thresher: Would you suggest any Thresher: The evening meal will be at Thresher: Coach Peterson had some di- Conover: One of the things that I have changes in the training table? the colleges for those periods other than fficulties concerning the relationship in, mind concerns people who are coming Conover: First thing I'm going to do the season or spring training. between academic and athletics at Rice. into Rice University, not only football away with is breakfast—all year long. Conover: Yes—just like it's been. How do you see football fitting into Thresher: How will you sell Rice Uni- the scheme of things at Rice Univer- versity to recruits? sity? Conover: Well there are a number of Conover: When I came to Rice Uni- things we are concentrating on when we versity last year with Coach Peterson I talk to recruits. -

Ruidoso, Nm 88345

... .f . .. .. ·Wal-Mart Man walks·to L opening Tuesday :raise funds i. .. 'Seep~ge6A Seepage 3A NO. 86 IN OUR 40TH YEAR 35e PER COpy . MONDA~MA~CH3,1986 . RUIDOSO, NM 88345 . Council, commission Patch",,"ork . , . adopt~mbulance progress policy· The Grindstone dam pro ject now (left) and one year ago (below) shows be to by FRANKIE JARRELL &mders presented four points of routed the scene. the significant amount of News Staff Writer a "basic" agreement he and Diane Sanders said point four states that in .cases where a call goes progress that has been Fisher, atto.rney for Southwest made in the canyon. An Lincoln County and Village of Community Health Services directly to any ambulance service uthat service shall respond to the . access road leading to Ruidoso offic~ Fri.day agreed to (parent organizationforRHVH)" the dam site was just be· adopt policy guidelines to coor had drafted. ., call if it has an' ambulance That agreement states in item available." .' ing started last year, and dinate all emergency medical care now is finished and providers in Lincoln County. one thatambuIance servicesinthis Discussions centered on how the A joint meeting called for 2 p.m. county are normally dispatched by dispatcher can determine the handling traffic. The ac at RuidoSo Village Han got off to a the Sheriffs Office or the Ruidoso closest ambulance service, and the tual dam location (left, late start after commissioners, Police. sugges.tion was made that upper left) now is a busy Ruidoso's. mayorandlegaladvisers Item two continues: u a dispat HresponSe time" should replace site of activity-last year for both governments and the cher ••• shall in all instances direct wording that suggests physical only thick forest stood Ruidoso-Hondo Valley Hospital the call to the. -

From Real Time to Reel Time: the Films of John Schlesinger

From Real Time to Reel Time: The Films of John Schlesinger A study of the change from objective realism to subjective reality in British cinema in the 1960s By Desmond Michael Fleming Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 School of Culture and Communication Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Produced on Archival Quality Paper Declaration This is to certify that: (i) the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD, (ii) due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, (iii) the thesis is fewer than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. Abstract The 1960s was a period of change for the British cinema, as it was for so much else. The six feature films directed by John Schlesinger in that decade stand as an exemplar of what those changes were. They also demonstrate a fundamental change in the narrative form used by mainstream cinema. Through a close analysis of these films, A Kind of Loving, Billy Liar, Darling, Far From the Madding Crowd, Midnight Cowboy and Sunday Bloody Sunday, this thesis examines the changes as they took hold in mainstream cinema. In effect, the thesis establishes that the principal mode of narrative moved from one based on objective realism in the tradition of the documentary movement to one which took a subjective mode of narrative wherein the image on the screen, and the sounds attached, were not necessarily a record of the external world. The world of memory, the subjective world of the mind, became an integral part of the narrative. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

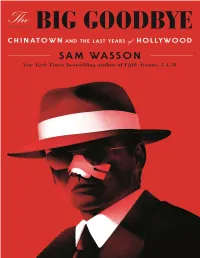

The Big Goodbye

Robert Towne, Edward Taylor, Jack Nicholson. Los Angeles, mid- 1950s. Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Flatiron Books ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For Lynne Littman and Brandon Millan We still have dreams, but we know now that most of them will come to nothing. And we also most fortunately know that it really doesn’t matter. —Raymond Chandler, letter to Charles Morton, October 9, 1950 Introduction: First Goodbyes Jack Nicholson, a boy, could never forget sitting at the bar with John J. Nicholson, Jack’s namesake and maybe even his father, a soft little dapper Irishman in glasses. He kept neatly combed what was left of his red hair and had long ago separated from Jack’s mother, their high school romance gone the way of any available drink. They told Jack that John had once been a great ballplayer and that he decorated store windows, all five Steinbachs in Asbury Park, though the only place Jack ever saw this man was in the bar, day-drinking apricot brandy and Hennessy, shot after shot, quietly waiting for the mercy to kick in.