Pippin 1 Geoffrey Pippin Easter 2014 Asian Studies Senior Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confronting Racism and Sexism

TheWomen's Movement in the United States: Confronting Racism and Sexism Leslie R.Wolfe At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that thc true revolution ary is guided by great feelings of love che Guevara Preface: A Personal Note This chapter presents some verbal snapshots of the U.S. women's movement in the context of gender and race relations. This has been central to my work and life since 1972-when I flrst went to work at the National Welfare Rights Organization and then to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights; and today it is in full flower in the work of the Center for Women Policy Studies. In all of these years, I have shared with many other feminists the mission to speak out about racism-plus-sexism as having a unique quality of oppression for women of color. We have talked about the importance of "doing our homework" about other sisters' origins, cul- tures, and histories. We have encouraged white feminists to be outspo- ken against racism and not to leave that task solely to women of color. We have insisted on our responsibility to root out the vestiges of racism in ourselves, in our organizations, and in our feminist theory and policy priorities. And we have talked to women of color as well about multiethnic visions of feminism and the importance of doing the hard work to break down racial. ethnic, and cultural barriers both to sisterhood and to the institutional change that will foreshadow an egal- itarian future. 231 232 Counvy Pottroits fheWomen's Movement in the United Stotes 255 Setting the Stager Defining premises Our Central sex. -

Game Play Mechanics in Old Monster Yarns Sugoroku

LEAPING MONSTERS AND REALMS OF PLAY: GAME PLAY MECHANICS IN OLD MONSTER YARNS SUGOROKU by FAITH KATHERINE KRESKEY A THESIS Presented to the Department of the History of Art and Architecture and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2012 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Faith Katherine Kreskey Title: Leaping Monsters and Realms of Play: Game Play Mechanics in Old Monster Yarns Sugoroku This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture by: Professor Akiko Walley Chairperson Professor Glynne Walley Member Professor Charles Lachman Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2012 ii © 2012 Faith Katherine Kreskey iii THESIS ABSTRACT Faith Katherine Kreskey Master of Arts Department of the History of Art and Architecture December 2012 Title: Leaping Monsters and Realms of Play: Game Play Mechanics in Old Monster Yarns Sugoroku Taking Utagawa Yoshikazu’s woodblock printed game board Monster Yarns as my case study, I will analyze how existing imagery and game play work together to create an interesting and engaging game. I will analyze the visual aspect of this work in great detail, discussing how the work is created from complex and disparate parts. I will then present a mechanical analysis of game play and player interaction with the print to fully address how this work functions as a game. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Kamigawa by Gaunlet AKA Waddle Proofread By

Kamigawa By Gaunlet AKA Waddle Proofread By The world of Kamigawa, positioned far from any other world known to the Walkers, is governed by the interplay between the mortals and the kami, minor gods or spirits of the world. However, when a child of the supreme kami, O-Kagachi, was stolen away, the physical and spiritual worlds gird for war against each other. The Kakuriyo, sometimes called the Reikai, is the spirit world where the kami dwell; its other half is that of the Utsushiyo where mortals live. Together they form a great sphere that makes the whole of the world. You have come at a troubling time, dear Jumper. The war with the spirit realm has begun. In a world of mysticism and honor, the war is brewing. Spirits launch attacks against humans as, in the shadows, a terror lurks just beyond sight. This world is filled with mysteries and it’s depths have yet to be properly understood. So many things are coming to light and old grudges are being settled wholesale and into this world you have entered. Take this 1000 CP to aid in your journey in this place. Age and Gender matter little here. Age: 1d8+20 Free Choice on Gender. Location Roll 1d8 or pay 100 CP for a free choice of location. 1. Towabara — A massive plain, the name means "eternal field". Within the Towabara is the Araba, the "ruined land", a blasted place filled with craters from kami attacks. Eiganjo Castle is in the center of the Araba. It is the fortification of daimyo Takeshi Konda and his samurai. -

Oriental Adventures James Wyatt

620_T12015 OrientalAdvCh1b.qxd 8/9/01 10:44 AM Page 2 ® ORIENTAL ADVENTURES JAMES WYATT EDITORS: GWENDOLYN F. M. KESTREL PLAYTESTERS: BILL E. ANDERSON, FRANK ARMENANTE, RICHARD BAKER, EIRIK BULL-HANSEN, ERIC CAGLE, BRAIN MICHELE CARTER CAMPBELL, JASON CARL, MICHELE CARTER, MAC CHAMBERS, TOM KRISTENSEN JENNIFER CLARKE WILKES, MONTE COOK , DANIEL COOPER, BRUCE R. CORDELL, LILY A. DOUGLAS, CHRISTIAN DUUS, TROY ADDITIONAL EDITING: DUANE MAXWELL D. ELLIS, ROBERT N. EMERSON, ANDREW FINCH , LEWIS A. FLEAK, HELGE FURUSETH, ROB HEINSOO, CORY J. HERNDON, MANAGING EDITOR: KIM MOHAN WILLIAM H. HEZELTINE, ROBERT HOBART, STEVE HORVATH, OLAV B. HOVET, TYLER T. HURST, RHONDA L. HUTCHESON, CREATIVE DIRECTOR: RICHARD BAKER JEFFREY IBACH, BRIAN JENKINS, GWENDOLYN F.M. KESTREL, TOM KRISTENSEN, CATIE A. MARTOLIN, DUANE MAXWELL, ART DIRECTOR: DAWN MURIN ANGEL LEIGH MCCOY, DANEEN MCDERMOTT, BRANDON H. MCKEE, ROBERT MOORE, DAVID NOONAN, SHERRY L. O’NEAL- GRAPHIC DESIGNER: CYNTHIA FLIEGE HANCOCK, TAMMY R. OVERSTREET, JOHN D. RATELIFF, RICH REDMAN, THOMAS REFSDAL, THOMAS M. REID, SEAN K COVER ARTIST: RAVEN MIMURA REYNOLDS, TIM RHOADES, MIKE SELINKER, JAMES B. SHARKEY, JR., STAN!, ED STARK, CHRISTIAN STENERUD, OWEN K.C. INTERIOR ARTISTS: MATT CAVOTTA STEPHENS, SCOTT B. THOMAS, CHERYL A. VANMATER-MINER, LARRY DIXON PHILIPS R. VANMATER-MINER, ALLEN WILKINS, PENNY WILLIAMS, SKIP WILLIAMS CRIS DORNAUS PRONUNCIATION HELP: DAVID MARTIN RON FOSTER, MOE MURAYAMA, CHRIS PASCUAL, STAN! RAVEN MIMURA ADDITIONAL THANKS: WAYNE REYNOLDS ED BOLME, ANDY HECKT, LUKE PETERSCHMIDT, REE SOESBEE, PAUL TIMM DARRELL RICHE RICHARD SARDINHA Dedication: To the people who have taught me about the cultures of Asia—Knight Biggerstaff, Paula Richman, and my father, RIAN NODDY B S David K. -

Samurai Champloo: Transnational Viewing Jiwon Ahn

Samurai Champloo: Transnational Viewing Jiwon Ahn From the original edition of How to Watch Television published in 2013 by New York University Press Edited by Ethan Thompson and Jason Mittell Accessed at nyupress.org/9781479898817 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND). 39 Samurai Champloo Transnational Viewing Jiwon Ahn Abstract: Television criticism usually addresses “what” TV is watched, and ofen “who” watches, but “where” TV is watched is less commonly considered vital to understanding it. In this look at the anime program Samurai Champloo, Jiwon Ahn argues for the importance of “where” to the meanings and pleasures of texts which—like anime—circulate in television’s global fows. Watching an imported or translated text on television is an increasingly ordinary experience in the current state of globalization. But what unique critical questions should we consider in order to make sense of such viewings? To understand our de- sire for and pleasure in viewing imported television texts, we need to consider how texts produced for overseas distribution are designed diferently for international audiences, and how this design may infect (or not) our viewing of them. Anime ofers a productive example in that the format’s long history of international circula- tion inevitably involved the development of textual strategies suited to transnational consumption, including, notably, an efort to balance exoticism with familiarity in terms of appeal. While the popularity of shows such as Dragon Ball Z (Cartoon Net- work, 1998–2005), Ranma ½ (Fuji Television, 1989–1992), and InuYasha (Cartoon Network, 2000–2004) on U.S. -

Chapter One Introduction

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1.Background of Study Japan has so many traditions of folklore that had inherited for generation whether in story form or in tradition form. With some creativity and existing technology that they had, some Japanese filmmaker has succeeded by making some Japanese folklore into more interesting form and well known by people whether inside Japan or outside Japan. According to Kitayama “Folklore is a stories shared by folk people from the past and these stories are similar to myths, except that they are related more to human matters than to supernatural beings” (Kitayama 2005: 85) By this quotation the writer argue that folklore is cultural product which is produced by people in the past and it is contained of myth and usually, the society will connect the folklore to supernatural even more to human matters. As emphasized by Lindahl, Although many people regard a “folktale” as a fictional form, I use the term here to apply to any traditional tale, whether its tellers consider it true, or false, or both. Thus, the scope of the tale extends far beyond fiction to encompass belief tales, personal experience stories, and accounts of major historical events (Lindahl, 2004: 200). Based on the quotation above, the writer argues that folklore acknowledges the practice of labeling narratives based on the element of belief, he also realizes the inherent story within each and the tendency of storytellers to use a little fiction and a little nonfiction in crafting their stories. Lindahl uses this terminology to put the focus on the storytellers themselves and help the reader to recognize the relationship between tale and teller. -

Friday Sept. 13 Saturday Sept. 14 Sunday Sept. 15

FRIDAY SEPT. 13 Main Panels: Panels: Panels: eGaming: Birch Table Top: Walnut Table Top: Walnut Screening 1 Screening 2 Vendors / Programming Chestnut Elm Cedar Artist Alley 12:00 PM Open Open Gaming Open Gaming Bodacious Space Pirates Tsubasa: Reservoir Closed 12:00 PM 12:30 PM (Episodes 1-4) Chronicles (Episodes 1-4) 12:30 PM 1:00 PM Cosplay Advanced (Wig Wig) Puyo Puyo Tetris Open 1:00 PM 1:30 PM 1:30 PM 2:00 PM Love Live (Episodes 1-4) Persona 4: The Animation 2:00 PM 2:30 PM The Villains of Paul St. Peter T-Doll Training: An Intro Horror as Social **Splendor Tutorial** (Episodes 1-4) 2:30 PM 3:00 PM to Girls Frontline Commentary Splendor Tournament 3:00 PM 3:30 PM 3:30 PM 4:00 PM Ludo Light Sabre Academy Autograph Session Guess that Pokemon! Intro to AnimeFargo: Dragonball FighterZ Azumanga Daioh Pretear (Episodes 1-4) 4:00 PM 4:30 PM Volunteering or Staffing (Episodes 1-4) 4:30 PM 5:00 PM 5:00 PM 5:30 PM Opening 5:30 PM 6:00 PM Open Gaming Relic Knights Carp Captor Sakura: xxxHolic (Episodes 1-4) 6:00 PM 6:30 PM Consent Culture in Anime Wonderful Wigs (Wig Clear Card (Episodes 1-4) 6:30 PM 7:00 PM Cosplay chess Multiplayer Oreo: Choose and Manga Wig) Super Smash Bros 7:00 PM 7:30 PM Your Group Adventure Ultimate 4-Player 7:30 PM 8:00 PM InuYasha Season 1 Anime Court Kiddy Grade (Episodes 1- Save Me! Lolipop Closed 8:00 PM 8:30 PM Cyber-Dance 8:15 - 9:15 4) (Episodes 1-4) 8:30 PM 9:00 PM Karaoke Open Gaming (After Dark) Open Gaming (After Dark) 9:00 PM 9:30 PM Shino and friends (DSP) MaximumWeeaboo: 80s- 9:30 PM 10:00 PM HD Remastered Open Digital Breakdown Hetalia: Axis Powers Cowboy Bebop (Episodes 10:00 PM 10:30 PM (Paranoia Game) (Episodes 1-26) 1-4) 10:30 PM 11:00 PM Red Dragon Inn (18+) - How I Remember It (18+) BDSM 101 safety (18+) 11:00 PM 11:30 PM (Snowmen) 11:30 PM 12:00 AM Closed Closed 12:00 AM 12:30 AM Werewolf Spiral into horror 2: 12:30 AM 1:00 AM The Panel That Doesn't Exist Uzumaki Boogaloo (18+) Closed 1:00 AM 1:30 AM (18+) 1:30 AM SATURDAY SEPT. -

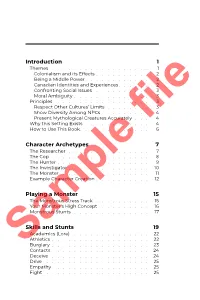

Introduction 1 Character Archetypes 7 Playing a Monster 15 Skills

Introduction 1 Themes..................1 Colonialism and its Effects..........2 Being a Middle Power............2 Canadian Identities and Experiences......2 Confronting Social Issues..........3 Moral Ambiguity..............3 Principles.................3 Respect Other Cultures’ Limits........3 Show Diversity Among NPCs.........4 Present Mythological Creatures Accurately...4 Why this Setting Exists............4 How to Use This Book.............6 Character Archetypes 7 The Researcher...............7 The Cop..................8 The Hunter.................9 The Investigator............... 10 The Monster................ 11 Example Character Creation.......... 12 Playing a Monster 15 The Monstrous Stress Track.......... 15 Your Monster’s High Concept......... 16 Monstrous Stunts.............. 17 Skills and Stunts 19 Academics (Lore).............. 22 Athletics.................. 22 SampleBurglary.................. 23 file Contacts.................. 24 Deceive.................. 24 Drive................... 25 Empathy.................. 25 Fight................... 25 Investigate................. 26 Notice................... 26 Physique.................. 27 Provoke.................. 27 Rapport.................. 28 Resources................. 28 Shoot................... 28 Stealth................... 30 Tech (Crafts)................ 30 Will.................... 31 Earth’s Secret History 33 Veilfall................... 33 Supernatural Immigration........... 35 The Cerulean Amendment.......... 36 Lifting the Veil................ 36 Organizations and NPCs 39 -

Tải Truyện Tiếng Hát Nơi Biển Cả

Trang đọc truyện online truyenhayhoan.com Tiếng hát nơi biển cả Chương 74 : Chương 74 Chương 73 Có vẻ như không cần nói gì nhiều thì ai cũng biết tình hình chiến trận đang diễn biến ra sao. Với thanh Katana ngang nhiên, can đảm pha lẫn chút liều mình khi dám chĩa thẳng mũi nhọn về vị thần của đại dương và bão tố… À không. Đó không hẳn chỉ là vị thần của thiên nhiên, mà còn chính là vị thần tượng trưng cho sự phẫn nộ, đau đớn, hối hận về những tội lỗi mà Tsubaki đã trải qua trong ba năm dài dằng dặc. Đối mặt với thần, đồng nghĩa với việc Tsubaki phải đối mặt với chính mình của quá khứ… Đối măt với sự thật rằng mình không có quyền được nhận sự tha thứ, nhưng mình vẫn phải dành lấy chiến thắng, dành lấy niềm tin lẫn sự hy vọng. _ Tsubaki Minamiya… cận vệ của cháu gái ta đấy sao? Lâu rồi không gặp nhỉ, nhãi ranh! _ Đúng là một cuộc gặp gỡ chẳng ra làm sao, xin lỗi vì đã bỏ trốn trong khoảng thời gian lâu như thế. Ba năm trôi qua ngươi cũng biết cách trang điểm quá chứ nhỉ. Biến hình thành bộ dạng của ta chắc thú vị lắm ha! Susanoo… Tố Trản Ô Tôn Susanoo no Mikoto, hiện diện trước Tsubaki bằng chính bộ dạng, gương mặt của hắn. Nói một cách chính xác thì ngài sử dụng dung mạo Tsubaki của ba năm trước… thời kỳ hoàng kim của một Đệ Nhất Kiếm Vũ Sư khi còn khoác trên người chiếc áo độc nhất, minh chứng cho người đủ thực lực trở thành hộ vệ cho cháu gái thần biển. -

Inuyasha Series OC Bio

InuYasha Series OC Bio: Characteristics: Name: Nihongo: Meaning: First: Middle: Last: Alias: N/A Race: Human/Daiyokai/Yokai/Hanyo/Specter/Kugutsu/ Extra to Race: Full/ ¾ /Half/ ¼ Type: Kappa/Kitsune/Nekomata/Omukade/Bakeitachi/Bird/Flea/Inu/Wolf/Spider/Mantis/Moth/Turtle/Rat/Tiger/Tree/ Oni/Thunder/Wind/Dragon/Panther/Oyster/Bat/Humanoid/Cat/Hair/Horse/Root/Cow/Shikigami/Tanuki/Crow/ Mirror/Badger/Flower/Toad/Bone/Lizard/Salamander/Ninja/Otter/Snake/Coyote/Monkey/Ape/Lynx/Catfish/Sc orpion/Bull/Sheep/Ram/ Gender: Male/Female/Male (Transgender)/Female (Transgender)/Intersex Sexual Orientation: Heterosexual/Homosexual/Bisexual/Pansexual/Asexual Age: Birthday: Time of Birth: Blood Type: A+/A-/B+/B-/AB+/AB-/O+/O-/Unknown Personality: Horoscope: Aries/Taurus/Gemini/Cancer/Leo/Virgo/Libra/Scorpio/Sagittarius/Capricon/Aquarius/Pisces Appearance: Hair: Color: Length: Style: Eye Color: Skin Color: Body: Weight: Child: Pre-Teen: Teenager: Adult: Senior: Height: Child: Pre-Teen: Teenager: Adult: Senior: Outfit(s): Child: Pre-Teen: Teenager: Adult: Senior: Images: Child: Pre-Teen: Teenager: Adult: Senior: Professional Status: Affiliation: Precious Affiliations: Abilities: Weapons: Loyalty: Enemies: Personal Status: Status: Relatives: Best Friend(s): Friends: Pet(s): Hobbies: Likes: Dislikes: Former Love Interest: Love Interest: Portrayal: Voice Actors: Child: Pre-Teen: Teenager: Adult: Senior: Face Claims: Child: Pre-Teen: Teenager: Adult: Senior: Curiosities: Favorite Food: Favorite Color: Favorite Movie: (OC that are in Modern Time) Favorite -

Salvation of the Snake, the Snake of Salvation : Buddhist-Shinto Conflict and Resolution

Salvation of the Snake, The Snake of Salvation : Buddhist-Shinto Conflict and Resolution W. Michael K e lse y INTRODUCTION Buddhism and ohinto have had a remarkably harmonious coex istence over the past fourteen centuries. This is most probably due to two factors: on the one hand, Shinto lacked a formal struc ture from which to organize resistance, and on the other, Buddhism had always assimilated the traditions native to the countries it entered. Even so, it is not realistic to maintain that the first period of contact between these two religions was completely free of strife. Indeed, one senses a sometimes violent conflict lurking beneath the surface of certain Japanese Buddhist stories. This conflict which accompanied Buddhism’s entry to the gates of the Japanese spirit also provided the basis for the Buddhist- Shinto syncretization that was to prove so remarkable in later years; what was first a minus was later to become a plus. This essay will examine Buddhist-Shinto relationships as seen in a single cluster of stories, namely, those having to do with snakes. In brief, my thesis is that we can find in these stories first conflict between Buddhism and Shinto, and then, as the relationships be tween the two settle down, a creative Buddhist use of those ancient Shinto aeities that appeared as reptiles. The malevolent reptilian deity existed in Japan before the in troduction of Buddhism, and it is initially regarded by the Bud dhists, as well as by other Japanese, as being an evil creature. As Buddhism took a deeper hold on the Japanese consciousness, how ever, the image of the violent snake—which never completely died out—came to be supplemented by that of a snake of salvation.