Lessons on Voting Reform from Britian's First Pr Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of UK Electoral Systems

Patrick Dunleavy and Helen Margetts The impact of UK electoral systems Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Dunleavy, Patrick and Margetts, Helen (2005) The impact of UK electoral systems. Parliamentary affairs, 58 (4). pp. 854-870. DOI: 10.1093/pa/gsi068 © 2005 Oxford University Press This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/3083/ Available in LSE Research Online: February 2008 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript accepted version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the published version may remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Forthcoming in Parliamentary Affairs, September 2005 THE IMPACT OF THE UK’S ELECTORAL SYSTEMS* Patrick Dunleavy and Helen Margetts In the immediate aftermath of the general election the Independent ran a whole-page headline illustrated with contrasting graphics showing ‘What we voted for’ and ‘What we got’, followed up by ‘…and why it’s time for change’.1 The paper launched a petition calling for a shift to a system that is fairer and more proportional, which in rapid time attracted tens of thousands of signatories, initially at a rate of more than 500 people a day. -

Manifesto 2011 SOLIDARITY with the SSP!

Holyrood Election Manifesto 2011 SOLIDARITY WITH THE SSP! “I am very pleased to support the elderly, a good education independent campaign of the SSP in the coming of private interests, a fully funded election. health service, decent housing - these All across Europe people are finding are not unreasonable demands. But their jobs threatened, wages and now they are revolutionary. The benefits cu t and the quality of life system cannot allow them. Which reduced. The great public institutions other party, to take but one example, that have been built by past now calls for full employment? generations are now to be Scotland has a long history of dismembered, sold off, privatised. radical struggle, like the great cities Blaming the bankers is not an of England. We should show solidarity adequate response. Socialists know with those around the world who fight that it is not individual greed but the for justice, peace and the rule of law. very system itself that generates these Socialism is the heart of that. A disasters. Private corporations and strong vote for the SSP would be the banks will always put profit before best news for ordinary people people, otherwise they would not keep wherever they live. And it would be up with their competitors. brilliant for Scotland - you might find Only a party that starts from the some of us were coming to work here independent interests of working even more than we do now!” people can begin to redress the balance. A secure job, care for the - Ken Loach 2 HOLYROOD ELECTION MANIFESTO 2011 CONTENTS Pages 4&5 -

Elections REFORM September 2015

TOPIC EXPLORATION PACK GCSE Theme: Elections REFORM September 2015 GCSE (9–1) Citizenship Studies Oxford Cambridge and RSA We will inform centres about any changes to the specification. We will also publish changes on our website. The latest version of our specification will always be the one on our website (www.ocr.org.uk) and this may differ from printed versions. Copyright © 2015 OCR. All rights reserved. Copyright OCR retains the copyright on all its publications, including the specifications. However, registered centres for OCR are permitted to copy material from this specification booklet for their own internal use. Oxford Cambridge and RSA Examinations is a Company Limited by Guarantee. Registered in England. Registered company number 3484466. Registered office: 1 Hills Road Cambridge CB1 2EU OCR is an exempt charity. This resource is an exemplar of the types of materials that will be provided to assist in the teaching of the new qualifications being developed for first teaching in 2016. It can be used to teach existing qualifications but may be updated in the future to reflect changes in the new qualifications. Please check the OCR website for updates and additional resources being released. We would welcome your feedback so please get in touch. Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Activity 1 ........................................................................................................................................ -

Scottish Parliament Elections: 1 May 2003 14.05.03

RESEARCH PAPER 03/46 Scottish Parliament 14 MAY 2003 Elections: 1 May 2003 This paper provides summary and detailed results of the second elections to the Scottish Parliament which took place on 1 May 2003. The paper provides data on voting trends and electoral turnout for constituencies, electoral regions and for Scotland as a whole. This paper is a companion volume to Library Research Papers 03/45 Welsh Assembly Elections and 03/44 Local Elections 2003. Matthew Leeke & Richard Cracknell SOCIAL & GENERAL STATISTICS SECTION HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers 03/32 Parliamentary Questions, Debate Contributions and Participation in 31.03.03 Commons Divisions 03/33 Economic Indicators [includes article: Changes to National Insurance 01.04.03 Contributions, April 2003] 03/34 The Anti-Social Behaviour Bill [Bill 83 of 2002-03] 04.04.03 03/35 Direct taxes: rates and allowances 2003-04-11 10.04.03 03/36 Unemployment by Constituency, March 2003 17.04.03 03/37 Economic Indicators [includes article: The current WTO trade round] 01.05.03 03/38 NHS Foundation Trusts in the Health and Social Care 01.05.03 (Community Health and Standards) Bill [Bill 70 of 2002-03] 03/39 Social Care Aspects of the Health and Social Care (Community Health 02.05.03 and Standards Bill) [Bill 70 of 2002-03] 03/40 Social Indicators 06.05.03 03/41 The Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) 06.05.03 Bill: Health aspects other than NHS Foundation Trusts [Bill 70 of 2002-03] 03/42 The Fire Services Bill [Bill 81 of 2002-03] 07.05.03 03/43 -

Strategic Coalition Voting: Evidence from Austria Meffert, Michael F.; Gschwend, Thomas

www.ssoar.info Strategic coalition voting: evidence from Austria Meffert, Michael F.; Gschwend, Thomas Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: SSG Sozialwissenschaften, USB Köln Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Meffert, M. F., & Gschwend, T. (2010). Strategic coalition voting: evidence from Austria. Electoral Studies, 29(3), 339-349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2010.03.005 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

Statement of Accounts of the Scottish Socialist Party at 31 December 2019

Statement of Accounts of the Scottish Socialist Party at 31st December 2019 Treasurer’s Statement SSP Accounts 2019 2019 will be remembered as the year that saw a general election victory for the Tories which saw them go from a position of a hung parliament to a parliamentary majority of 80 with the Tories winning seats in traditional working class areas that previously would never have considered voting Tory, confirming Johnstone as the Tory PM with the largest majority in living memory. A Tory government which has become the norm in politics in Scotland. No matter how the working class majority in Scotland vote, there will always be a Unionist majority in Westminster. The Scottish Socialist Party have continued to campaign on our central policy of an independent socialist Scotland being our cornerstone policy which highlights that the only path for real democratic change is an independent Scotland that can challenge Scotland’s democratic deficit. Scottish independence will be democratically won by the Scottish people campaigning in our local communities, on issues that affect the daily life of working class Scotland. The SSP continues to fight austerity and campaigns for workers rights, the end of zero hour contracts and ‘£10 per hour now minimum wage’ as part of our continuing campaign for an independent socialist Scotland. James McVicar SSP National Treasurer. Income and Expenditure Account Year ended 31st December 2019 Income Membership and Subscriptions 32727 Donations 1284 Fundraising 1562 Merchandising and Sundries 291 Total income -

The Many Faces of Strategic Voting

Revised Pages The Many Faces of Strategic Voting Strategic voting is classically defined as voting for one’s second pre- ferred option to prevent one’s least preferred option from winning when one’s first preference has no chance. Voters want their votes to be effective, and casting a ballot that will have no influence on an election is undesirable. Thus, some voters cast strategic ballots when they decide that doing so is useful. This edited volume includes case studies of strategic voting behavior in Israel, Germany, Japan, Belgium, Spain, Switzerland, Canada, and the United Kingdom, providing a conceptual framework for understanding strategic voting behavior in all types of electoral systems. The classic definition explicitly considers strategic voting in a single race with at least three candidates and a single winner. This situation is more com- mon in electoral systems that have single- member districts that employ plurality or majoritarian electoral rules and have multiparty systems. Indeed, much of the literature on strategic voting to date has considered elections in Canada and the United Kingdom. This book contributes to a more general understanding of strategic voting behavior by tak- ing into account a wide variety of institutional contexts, such as single transferable vote rules, proportional representation, two- round elec- tions, and mixed electoral systems. Laura B. Stephenson is Professor of Political Science at the University of Western Ontario. John Aldrich is Pfizer- Pratt University Professor of Political Science at Duke University. André Blais is Professor of Political Science at the Université de Montréal. Revised Pages Revised Pages THE MANY FACES OF STRATEGIC VOTING Tactical Behavior in Electoral Systems Around the World Edited by Laura B. -

Survey Report

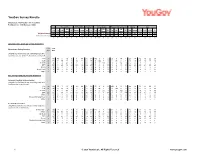

YouGov Survey Results Sample Size: 1089 Adults (16+) in Scotland Fieldwork: 6th - 10th November 2020 Vote in 2019 EU Ref 2016 Indy Ref Voting intention Holyrood Voting intention Gender Age Lib Lib Lib Total Con Lab SNP Remain Leave Yes No Con Lab SNP Con Lab SNP Male Female 16-24 25-49 50-64 65+ Dem Dem Dem Weighted sample 1089 203 150 77 363 551 296 411 509 145 138 33 425 156 119 50 463 524 565 142 430 271 246 Unweighted Sample 1089 238 155 69 392 577 304 398 489 168 141 32 432 182 122 51 469 472 617 123 402 268 296 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % WESTMINSTER HEADLINE VOTING INTENTION 6-10 6-10 Westminster Voting Intention Aug Nov [Weighted by likelihood to vote, excluding those who would not vote, are under 18, don't know, or refused] Con 20 19 75 6 15 0 8 44 5 31 100 0 0 0 90 5 14 1 23 14 12 10 22 31 Lab 16 17 11 60 24 4 20 11 5 27 0 100 0 0 4 89 9 4 15 19 18 15 17 20 Lib Dem 5 4 1 4 46 0 7 1 0 9 0 0 100 0 1 2 69 0 5 4 3 6 1 7 SNP 54 53 3 25 10 94 60 36 84 27 0 0 0 100 1 2 5 93 46 60 50 61 55 40 Green 2 3 0 4 5 1 3 0 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 2 3 2 3 3 7 3 3 0 Brexit Party 2 3 10 1 0 0 1 5 1 5 0 0 0 0 4 0 0 0 4 1 9 2 1 2 Other 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 2 0 0 2 1 0 HOLYROOD HEADLINE VOTING INTENTION Holyrood Headline Voting Intention [Weighted by likelihood to vote, excluding those who would not vote or don't know] Con 20 19 75 7 13 0 10 44 5 33 87 4 2 0 100 0 0 0 24 14 13 11 20 33 Lab 14 15 11 53 19 3 17 9 5 22 4 80 8 1 0 100 0 0 13 16 17 13 14 18 Lib Dem 6 6 4 6 47 1 8 4 1 11 4 3 90 1 0 0 100 0 7 6 4 6 4 10 SNP 57 56 5 -

CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach Agus an Rùnaire No A' Bhan- Ritnaire Aige, a Dhol Limcheall Air an Roinn I R ^ » Eòrpa Air Sgath Nan Cànain Bheaga

No. 105 Spring 1999 £2.00 • Gaelic in the Scottish Parliament • Diwan Pressing on • The Challenge of the Assembly for Wales • League Secretary General in South Armagh • Matearn? Drew Manmn Hedna? • Building Inter-Celtic Links - An Opportunity through Sport for Mannin ALBA: C O M U N N B r e i z h CEILTEACH • BREIZH: KEVRE KELTIEK • CYMRU: UNDEB CELTAIDD • EIRE: CONRADH CEILTEACH • KERNOW: KESUNYANS KELTEK • MANNIN: CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach agus an rùnaire no a' bhan- ritnaire aige, a dhol limcheall air an Roinn i r ^ » Eòrpa air sgath nan cànain bheaga... Chunnaic sibh iomadh uair agus bha sibh scachd sgith dhen Phàrlamaid agus cr 1 3 a sliopadh sibh a-mach gu aighcaraeh air lorg obair sna cuirtean-lagha. Chan eil neach i____ ____ ii nas freagarraiche na sibh p-fhèin feadh Dainmheag uile gu leir! “Ach an aontaich luchd na Pàrlamaid?” “Aontaichidh iad, gun teagamh... nach Hans Skaggemk, do chord iad an òraid agaibh mu cor na cànain againn ann an Schleswig-Holstein! Abair gun robh Hans lan de Ball Vàidaojaid dh’aoibhneas. Dhèanadh a dhicheall air sgath nan cànain beaga san Roinn Eòrpa direach mar a rinn e airson na Daineis ann atha airchoireiginn, fhuair Rinn Skagerrak a dhicheall a an Schieswig-I lolstein! Skaggerak ]¡l¡r ori dio-uglm ami an mhinicheadh nach robh e ach na neo-ncach “Ach tha an obair seo ro chunnartach," LSchlesvvig-Molstein. De thuirt e sa Phàrlamaid. Ach cha do thuig a cho- arsa bodach na Pàrlamaid gu trom- innte ach:- ogha idir. chridheach. “Posda?” arsa esan. -

From Social Democracy Back to No Ideology? - the Scottish National Party and Ideological Change in a Multi-Level Electoral Setting

From Social Democracy back to No Ideology? - The Scottish National Party and Ideological Change in a Multi-level Electoral Setting Peter Lynch Accepted for publication in Regional & Federal Studies published by Taylor and Francis Introduction Nationalist and regionalist parties have often been characterised as ideologically heterogeneous (Hix and Lord, 1997; De Winter and Türsan, 1998). This situation makes regionalist parties difficult to classify in conventional left-right terms though viewing these parties as an ideological family is to misunderstand their role and significance. Ideological profile can be understood as a secondary characteristic of regionalist parties, as opposed to their primary characteristic of support for self- government – the core business of autonomy (De Winter, 1998, 208-9): which in itself contains a variety of constitutional options to reorganise the territorial distribution of power within a state (Rokkan and Urwin, 1983). However, though ideological positioning may be a secondary characteristic, most regionalist parties have adopted an ideology – in the SNP’s case social democracy. As will be explained below, the reasons for adopting an ideology in itself, in addition to a particular ideology, are complex. For the SNP, the ideological position of elites, the policy preferences of the party’s membership and the adoption of an electoral strategy to challenge a dominant political party in the region (Labour) were all influential. The adoption of an ideological position was not always uncontroversial but became easier due to party system change (the electoral decline of the Conservatives in Scotland from the 1960s), as the SNP came to focus much of its attention on Labour as its primary competitor. -

Strengthening New Brunswick's Democracy

Strengthening New Brunswick’s Democracy Select Committee Discussion Paper on Electoral Reform July 2016 Strengthening New Brunswick’s Democracy Discussion Paper July 2016 Published by: Government of New Brunswick PO Box 6000 Fredericton, New Brunswick E3B 5H1 Canada Printed in New Brunswick ISBN 978-1- 4605-1033-9 (Print Bilingual) ISBN 978-1- 4605-1034-6 (PDF English) ISBN 978-1- 4605-1035-3 (PDF French) 10744 Table of Contents Select Committee on Electoral Reform 1 Message from the Government House Leader 2 How to use this discussion paper 3 Part 1: Introduction 4 Part 2: Making a more effective Legislature 8 Chapter 1: Eliminating barriers to entering politics for underrepresented groups 8 Chapter 2: Investigating means to improve participation in democracy 12 Internet voting 18 Part 3: Other electoral reform matters 20 Chapter 1: Election dates 20 Chapter 2: Election financing 21 Part 4: Conclusion 24 Part 5 : Appendices 25 Appendix A - Families of electoral systems 25 Appendix B - Voting systems 26 Appendix C - First-Past-the-Post 31 Appendix D - Preferential ballot voting: How does it work? 32 Appendix E- Election dates in New Brunswick 34 Appendix F - Fixed election dates: jurisdictional scan 36 Appendix G- Limits and expenses: Adjustments for inflation 37 Appendix H - Contributions: Limits and allowable sources jurisdictional scan 38 Appendix I - Mandate of the Parliamentary Special Committee on Electoral Reform 41 Appendix J - Glossary 42 Appendix K - Additional reading 45 Select Committee on Electoral Reform The Legislature’s Select Committee on Electoral Reform The committee is to table its final report at the Legislative is being established to examine democratic reform in the Assembly in January 2017. -

THE DEVOLVED PARTY SYSTEMS of the UNITED KINGDOM Sub-National Variations from the National Model

PARTY POLITICS VOL 11. No.6 pp. 654–673 Copyright © 2005 SAGE Publications London Thousand Oaks New Delhi www.sagepublications.com THE DEVOLVED PARTY SYSTEMS OF THE UNITED KINGDOM Sub-national Variations from the National Model Robert E. Bohrer II and Glen S. Krutz ABSTRACT In this article we examine the emerging party systems of the devolved environments, with an eye toward shedding light on the factors that influence the number of parties in a system where parties are already mobilized but the institutional context is new. Our findings demonstrate that electoral rules have an independent effect on the number of parties. More specifically, the use of proportional representation has increased the number of parties. In addition, two social cleavage structure factors appear to affect the design of the party system: class and center– periphery. All of these forces lead to a more complex governing arrange- ment in the devolved settings than that of the United Kingdom. KEY WORDS Ⅲ cleavages Ⅲ devolution Ⅲ mixed-member proportional representa- tion Ⅲ plurality Introduction The end of the twentieth century marked a shift in the political structure of the United Kingdom (UK). In the summer of 1999, the Scottish Parliament convened for the first time in nearly 300 years, while similar institutions opened in Wales and Northern Ireland. While emanating from Westminster, the devolved institutions varied a great deal from both the British model of parliament as well as from one another, though all three continued to remain subject, to varying extents, to the functioning of the British system. The advent of sub-national government in the UK offers numerous oppor- tunities for studying the effects of varying types of institutions, the expan- sion of issue agendas and the dynamics of multi-level governance.