Call for Papers the Issues Raised by the Scottish Referendum and Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manifesto 2011 SOLIDARITY with the SSP!

Holyrood Election Manifesto 2011 SOLIDARITY WITH THE SSP! “I am very pleased to support the elderly, a good education independent campaign of the SSP in the coming of private interests, a fully funded election. health service, decent housing - these All across Europe people are finding are not unreasonable demands. But their jobs threatened, wages and now they are revolutionary. The benefits cu t and the quality of life system cannot allow them. Which reduced. The great public institutions other party, to take but one example, that have been built by past now calls for full employment? generations are now to be Scotland has a long history of dismembered, sold off, privatised. radical struggle, like the great cities Blaming the bankers is not an of England. We should show solidarity adequate response. Socialists know with those around the world who fight that it is not individual greed but the for justice, peace and the rule of law. very system itself that generates these Socialism is the heart of that. A disasters. Private corporations and strong vote for the SSP would be the banks will always put profit before best news for ordinary people people, otherwise they would not keep wherever they live. And it would be up with their competitors. brilliant for Scotland - you might find Only a party that starts from the some of us were coming to work here independent interests of working even more than we do now!” people can begin to redress the balance. A secure job, care for the - Ken Loach 2 HOLYROOD ELECTION MANIFESTO 2011 CONTENTS Pages 4&5 -

Scottish Parliament Elections: 1 May 2003 14.05.03

RESEARCH PAPER 03/46 Scottish Parliament 14 MAY 2003 Elections: 1 May 2003 This paper provides summary and detailed results of the second elections to the Scottish Parliament which took place on 1 May 2003. The paper provides data on voting trends and electoral turnout for constituencies, electoral regions and for Scotland as a whole. This paper is a companion volume to Library Research Papers 03/45 Welsh Assembly Elections and 03/44 Local Elections 2003. Matthew Leeke & Richard Cracknell SOCIAL & GENERAL STATISTICS SECTION HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers 03/32 Parliamentary Questions, Debate Contributions and Participation in 31.03.03 Commons Divisions 03/33 Economic Indicators [includes article: Changes to National Insurance 01.04.03 Contributions, April 2003] 03/34 The Anti-Social Behaviour Bill [Bill 83 of 2002-03] 04.04.03 03/35 Direct taxes: rates and allowances 2003-04-11 10.04.03 03/36 Unemployment by Constituency, March 2003 17.04.03 03/37 Economic Indicators [includes article: The current WTO trade round] 01.05.03 03/38 NHS Foundation Trusts in the Health and Social Care 01.05.03 (Community Health and Standards) Bill [Bill 70 of 2002-03] 03/39 Social Care Aspects of the Health and Social Care (Community Health 02.05.03 and Standards Bill) [Bill 70 of 2002-03] 03/40 Social Indicators 06.05.03 03/41 The Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) 06.05.03 Bill: Health aspects other than NHS Foundation Trusts [Bill 70 of 2002-03] 03/42 The Fire Services Bill [Bill 81 of 2002-03] 07.05.03 03/43 -

Lessons on Voting Reform from Britian's First Pr Elections

WHAT WE ALREADY KNOW: LESSONS ON VOTING REFORM FROM BRITIAN'S FIRST PR ELECTIONS by Philip Cowley, University of Hull John Curtice, Strathclyde UniversityICREST Stephen Lochore, University of Hull Ben Seyd, The Constitution Unit April 2001 WHAT WE ALREADY KNOW: LESSONS ON VOTING REFORM FROM BRITIAN'S FIRST PR ELECTIONS Published by The Constitution Unit School of Public Policy UCL (University College London) 29/30 Tavistock Square London WClH 9QU Tel: 020 7679 4977 Fax: 020 7679 4978 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit/ 0 The Constitution Unit. UCL 200 1 This report is sold subject ot the condition that is shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. First published April 2001 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ..................................................................................4 Voters' attitudes to the new electoral systems ...........................................................4 Voters' behaviour under new electoral systems ......................................................... 4 Once elected .... The effect of PR on the Scottish Parliament in Practice ..................5 Voter Attitudes to the New Electoral Systems ............................................6 -

Statement of Accounts of the Scottish Socialist Party at 31 December 2019

Statement of Accounts of the Scottish Socialist Party at 31st December 2019 Treasurer’s Statement SSP Accounts 2019 2019 will be remembered as the year that saw a general election victory for the Tories which saw them go from a position of a hung parliament to a parliamentary majority of 80 with the Tories winning seats in traditional working class areas that previously would never have considered voting Tory, confirming Johnstone as the Tory PM with the largest majority in living memory. A Tory government which has become the norm in politics in Scotland. No matter how the working class majority in Scotland vote, there will always be a Unionist majority in Westminster. The Scottish Socialist Party have continued to campaign on our central policy of an independent socialist Scotland being our cornerstone policy which highlights that the only path for real democratic change is an independent Scotland that can challenge Scotland’s democratic deficit. Scottish independence will be democratically won by the Scottish people campaigning in our local communities, on issues that affect the daily life of working class Scotland. The SSP continues to fight austerity and campaigns for workers rights, the end of zero hour contracts and ‘£10 per hour now minimum wage’ as part of our continuing campaign for an independent socialist Scotland. James McVicar SSP National Treasurer. Income and Expenditure Account Year ended 31st December 2019 Income Membership and Subscriptions 32727 Donations 1284 Fundraising 1562 Merchandising and Sundries 291 Total income -

Survey Report

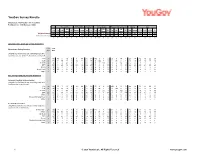

YouGov Survey Results Sample Size: 1089 Adults (16+) in Scotland Fieldwork: 6th - 10th November 2020 Vote in 2019 EU Ref 2016 Indy Ref Voting intention Holyrood Voting intention Gender Age Lib Lib Lib Total Con Lab SNP Remain Leave Yes No Con Lab SNP Con Lab SNP Male Female 16-24 25-49 50-64 65+ Dem Dem Dem Weighted sample 1089 203 150 77 363 551 296 411 509 145 138 33 425 156 119 50 463 524 565 142 430 271 246 Unweighted Sample 1089 238 155 69 392 577 304 398 489 168 141 32 432 182 122 51 469 472 617 123 402 268 296 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % WESTMINSTER HEADLINE VOTING INTENTION 6-10 6-10 Westminster Voting Intention Aug Nov [Weighted by likelihood to vote, excluding those who would not vote, are under 18, don't know, or refused] Con 20 19 75 6 15 0 8 44 5 31 100 0 0 0 90 5 14 1 23 14 12 10 22 31 Lab 16 17 11 60 24 4 20 11 5 27 0 100 0 0 4 89 9 4 15 19 18 15 17 20 Lib Dem 5 4 1 4 46 0 7 1 0 9 0 0 100 0 1 2 69 0 5 4 3 6 1 7 SNP 54 53 3 25 10 94 60 36 84 27 0 0 0 100 1 2 5 93 46 60 50 61 55 40 Green 2 3 0 4 5 1 3 0 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 2 3 2 3 3 7 3 3 0 Brexit Party 2 3 10 1 0 0 1 5 1 5 0 0 0 0 4 0 0 0 4 1 9 2 1 2 Other 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 2 0 0 2 1 0 HOLYROOD HEADLINE VOTING INTENTION Holyrood Headline Voting Intention [Weighted by likelihood to vote, excluding those who would not vote or don't know] Con 20 19 75 7 13 0 10 44 5 33 87 4 2 0 100 0 0 0 24 14 13 11 20 33 Lab 14 15 11 53 19 3 17 9 5 22 4 80 8 1 0 100 0 0 13 16 17 13 14 18 Lib Dem 6 6 4 6 47 1 8 4 1 11 4 3 90 1 0 0 100 0 7 6 4 6 4 10 SNP 57 56 5 -

CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach Agus an Rùnaire No A' Bhan- Ritnaire Aige, a Dhol Limcheall Air an Roinn I R ^ » Eòrpa Air Sgath Nan Cànain Bheaga

No. 105 Spring 1999 £2.00 • Gaelic in the Scottish Parliament • Diwan Pressing on • The Challenge of the Assembly for Wales • League Secretary General in South Armagh • Matearn? Drew Manmn Hedna? • Building Inter-Celtic Links - An Opportunity through Sport for Mannin ALBA: C O M U N N B r e i z h CEILTEACH • BREIZH: KEVRE KELTIEK • CYMRU: UNDEB CELTAIDD • EIRE: CONRADH CEILTEACH • KERNOW: KESUNYANS KELTEK • MANNIN: CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach agus an rùnaire no a' bhan- ritnaire aige, a dhol limcheall air an Roinn i r ^ » Eòrpa air sgath nan cànain bheaga... Chunnaic sibh iomadh uair agus bha sibh scachd sgith dhen Phàrlamaid agus cr 1 3 a sliopadh sibh a-mach gu aighcaraeh air lorg obair sna cuirtean-lagha. Chan eil neach i____ ____ ii nas freagarraiche na sibh p-fhèin feadh Dainmheag uile gu leir! “Ach an aontaich luchd na Pàrlamaid?” “Aontaichidh iad, gun teagamh... nach Hans Skaggemk, do chord iad an òraid agaibh mu cor na cànain againn ann an Schleswig-Holstein! Abair gun robh Hans lan de Ball Vàidaojaid dh’aoibhneas. Dhèanadh a dhicheall air sgath nan cànain beaga san Roinn Eòrpa direach mar a rinn e airson na Daineis ann atha airchoireiginn, fhuair Rinn Skagerrak a dhicheall a an Schieswig-I lolstein! Skaggerak ]¡l¡r ori dio-uglm ami an mhinicheadh nach robh e ach na neo-ncach “Ach tha an obair seo ro chunnartach," LSchlesvvig-Molstein. De thuirt e sa Phàrlamaid. Ach cha do thuig a cho- arsa bodach na Pàrlamaid gu trom- innte ach:- ogha idir. chridheach. “Posda?” arsa esan. -

From Social Democracy Back to No Ideology? - the Scottish National Party and Ideological Change in a Multi-Level Electoral Setting

From Social Democracy back to No Ideology? - The Scottish National Party and Ideological Change in a Multi-level Electoral Setting Peter Lynch Accepted for publication in Regional & Federal Studies published by Taylor and Francis Introduction Nationalist and regionalist parties have often been characterised as ideologically heterogeneous (Hix and Lord, 1997; De Winter and Türsan, 1998). This situation makes regionalist parties difficult to classify in conventional left-right terms though viewing these parties as an ideological family is to misunderstand their role and significance. Ideological profile can be understood as a secondary characteristic of regionalist parties, as opposed to their primary characteristic of support for self- government – the core business of autonomy (De Winter, 1998, 208-9): which in itself contains a variety of constitutional options to reorganise the territorial distribution of power within a state (Rokkan and Urwin, 1983). However, though ideological positioning may be a secondary characteristic, most regionalist parties have adopted an ideology – in the SNP’s case social democracy. As will be explained below, the reasons for adopting an ideology in itself, in addition to a particular ideology, are complex. For the SNP, the ideological position of elites, the policy preferences of the party’s membership and the adoption of an electoral strategy to challenge a dominant political party in the region (Labour) were all influential. The adoption of an ideological position was not always uncontroversial but became easier due to party system change (the electoral decline of the Conservatives in Scotland from the 1960s), as the SNP came to focus much of its attention on Labour as its primary competitor. -

THE DEVOLVED PARTY SYSTEMS of the UNITED KINGDOM Sub-National Variations from the National Model

PARTY POLITICS VOL 11. No.6 pp. 654–673 Copyright © 2005 SAGE Publications London Thousand Oaks New Delhi www.sagepublications.com THE DEVOLVED PARTY SYSTEMS OF THE UNITED KINGDOM Sub-national Variations from the National Model Robert E. Bohrer II and Glen S. Krutz ABSTRACT In this article we examine the emerging party systems of the devolved environments, with an eye toward shedding light on the factors that influence the number of parties in a system where parties are already mobilized but the institutional context is new. Our findings demonstrate that electoral rules have an independent effect on the number of parties. More specifically, the use of proportional representation has increased the number of parties. In addition, two social cleavage structure factors appear to affect the design of the party system: class and center– periphery. All of these forces lead to a more complex governing arrange- ment in the devolved settings than that of the United Kingdom. KEY WORDS Ⅲ cleavages Ⅲ devolution Ⅲ mixed-member proportional representa- tion Ⅲ plurality Introduction The end of the twentieth century marked a shift in the political structure of the United Kingdom (UK). In the summer of 1999, the Scottish Parliament convened for the first time in nearly 300 years, while similar institutions opened in Wales and Northern Ireland. While emanating from Westminster, the devolved institutions varied a great deal from both the British model of parliament as well as from one another, though all three continued to remain subject, to varying extents, to the functioning of the British system. The advent of sub-national government in the UK offers numerous oppor- tunities for studying the effects of varying types of institutions, the expan- sion of issue agendas and the dynamics of multi-level governance. -

WELSH ASSEMBLY ELECTION STUDY, 1999 NOTE to USERS (19 July 2000)

CREST CENTRE FOR RESEARCH INTO ELECTIONS AND SOCIAL TRENDS An ESRC Research Centre 35 Northampton Square at London EC1V 0AX The National Centre for Social Research & Department of Sociology, University of Oxford Telephone: 020-7250 1866 WELSH ASSEMBLY ELECTION STUDY, 1999 NOTE TO USERS (19 July 2000) This note provides information in brief about the Welsh Assembly Election Study 1999 (WAES). It accompanies the final version of the file (waes99.por). For further details of the study, see Thomson, K. et al (forthcoming), Welsh Assembly Election Study 1999: Technical Report, London: National Centre for Social Research. About the survey The WAES was conducted jointly by the Institute for Welsh Politics, University of Wales, Aberystwyth and the Centre for Research into Elections and Social Trends (CREST). CREST is an Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) funded Research Centre based jointly at the National Centre for Social Research (formerly SCPR) and the Department of Sociology, University of Oxford. The study was funded by an ESRC grant (R000238070). The module on the new electoral systems was developed jointly by the Constitution Unit, University College London and CREST and was funded by a separate ESRC grant (L327253017). The WAES was developed in close co-ordination with the 1999 Scottish Social Attitudes Survey (SSA), which served as a Scottish Parliamentary Election Study (SPES). Large parts of the questionnaire are identical or functional equivalent in order to make comparisons between Scotland and Wales possible. The SSA/SPES data file will be deposited with the Data Archive at a later time. The WAES incorporated a methodological experiment to assess the feasibility of conducting election studies on the telephone (see Nicolaas, G. -

Download Our Media Guide in PDF Format

1 EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT INFORMATION OFFICE IN THE UK MEDIA GUIDE 2014 - 2019 This guide provides journalists with information on: • The European Parliament and its activities • The 2009 and 2014 European elections • A Who’s Who in the European Parliament • Press contacts • What the UK Office does Björn Kjellström Olga Dziewulska Head of UK Office Press Attachée Tel: 020 7227 4325 Tel: 020 7227 4335 Disclaimer: All information in this guide was true and correct at the time of publication. Updated information can be found on our website. www.europarl.org.uk @EPinUK 2 3 Introduction by Björn Kjellström, Head of the European Parliament Information Office in the UK Every 5 years over 500 million people in the EU have the power to choose who will represent them in the European Parliament, the world's most open and only directly elected international parliament. Our mission is to raise awareness of its role and powers, of how political differences within it are played out and of how decisions taken by its Members affect the UK. These decisions have a huge impact on everyday life and it makes a big difference who decides on our behalf. Since journalists and the media in the UK play a key role in informing citizens about how the work of the European Parliament affects them, we hope that you will find this guide useful. 4 The European Parliament Information Office in the UK Our Role: We do our best to reach as broad a spectrum of society as we can – both face to face, online and in print. -

Chapter 2 Policy-Making Capacity of Political Parties in Wales

Chapter 2 Policy-making Capacity of Political Parties in Wales Anwen Elias 2 Policy-making Capacity of Political Parties in Wales Anwen Elias Introduction Political parties are central to any democratic political system. They are a key linkage between citizens and government. By contesting elections, political parties aim to mobilise popular support for a particular vision of how society should be organised. Translating this vision into concrete policies presents parties with major challenges. It tests their ability to respond to and reflect the needs and aspirations of their supporters, and to come up with appropriate solutions that can improve society. This paper considers the extent to which political parties in post-devolution Wales have been able to meet these challenges. The empirical evidence presented here draws on interviews undertaken during July and August 2012 with representatives of the main Welsh political parties - Welsh Labour, Welsh Conservatives, Welsh Liberal Democrats and Plaid Cymru. A full list of interviews is provided in Appendix 1. The paper is divided into two parts. The first outlines the current capacity and procedures for making policy within the Welsh parties. The aim is to identify changes in policy- making capacity in the run-up to, and since, the creation of the National Assembly. Drawing on this empirical evidence, the second section identifies areas of policy under-capacity and makes recommendations for addressing these weaknesses. Particular attention is paid to resources for policy development within government, and the public funding for policy development within political parties more generally. Dynamics of policy-making in Wales’ political parties This section outlines the process by which policy is generally made in each of Wales’s political parties, and the ways in which this has evolved in the post-devolution period. -

Devolution of Power in England, Scotland and Wales

Devolution of Power in England, Scotland and Wales Executive Council Statement to the 2003 Annual Delegate Meeting ContentsContents Introduction Page 2 Background Page 3 Voting for Devolution Page 4 The Scottish and Welsh General Elections Page 7 Usdaw’s General Election Campaign Page 10 Labour’s Policies for Scotland Page 12 Labour’s Policies for Wales Page 13 Campaigning after the Scottish and Welsh General Elections Page 14 English Regional Devolution Page 19 Your Region, Your Choice: The Regional Assemblies (Preparations) Bill Page 20 Conclusion Page 23 Appendices Page 24 G Usdaw’s Political Co-ordinators Page 24 G Application Form to Join the Labour Party Page 25 G Application for Constituency Labour Party Affiliation Fees Page 26 1 Devolution of Power in England, Scotland and Wales IntroductionIntroduction When the Labour Party promised the offer of devolved government to Scotland and Wales in the 1997 manifesto, no one would have guessed that within six months referenda would have been won in both countries and the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly set up and elected 18 months later. But devolution to Scotland and Wales has been delivered and the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly are already making a difference to our members’ lives. The elections in Scotland and Wales on 1 May 2003 will mark another milestone when the Parliament and Assembly are elected for another term in office. But those elections will be very important ones. The people of Scotland and Wales have the power to decide whether they want the Parliament and Assembly to continue to concentrate on improving public services and the way of life, or do they want them to focus on fighting for more power to be devolved? This paper sets out the choices for our members: the powers of the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly, the difference that they can make for our members and the ways we can use these powerful devolved institutions to fight for the issues that matter to us.