Banti Stages Artemisia Gentileschi: Intersections of Painting and Performance on the Modern Italian Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baroque and Rococo Art and Architecture 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BAROQUE AND ROCOCO ART AND ARCHITECTURE 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert Neuman | 9780205951208 | | | | | Baroque and Rococo Art and Architecture 1st edition PDF Book Millon Published by George Braziller, Inc. He completed two chapters and a table of con- tents for a projected five-volume treatise on painting, Discorso intorno alle immagini sacre e profane, published in part in , which, although directed at a Bolognese audience, had a great impact on artistic practice throughout the Italian peninsula. As Rubenists they painted in a similar manner; indeed contempo- raries called both "the Van Dyck of France" because they borrowed so considerably from Flemish Baroque pictorial tradition. United Kingdom. Francis ca. Both authors portray the sim- artists to study its sensuous and emot1onal ly stimulating effects. Create a Want BookSleuth Can't remember the title or the author of a book? Photographs by Wim Swaan. Henry A. Championing the that he took liberties with generally accepted ideas concept of art as the Bible of the illiterate, and pressing for regarding the Day of Judgment. Dust Jacket Condition: None. The university also prompted a strong antiquarian tradition among collectors, who sought out ancient sculpture and encouraged historical subjects in painting. Published by George Braziller To browse Academia. Thus Louis XIV, worshiping from the balcony, ruler or noble and focused on status rather than personal- appeared as successor to the great rulers of the past, spe- ity. Millon, Vincent Scully Jr. Gently used, light corner wear; crease to the spine. Sean B. The author, former Director of the Courtauld Institute of Art, is known internationally for his many works on French and Italian architecture and painting. -

The Symbolism of Blood in Two Masterpieces of the Early Italian Baroque Art

The Symbolism of blood in two masterpieces of the early Italian Baroque art Angelo Lo Conte Throughout history, blood has been associated with countless meanings, encompassing life and death, power and pride, love and hate, fear and sacrifice. In the early Baroque, thanks to the realistic mi of Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi, blood was transformed into a new medium, whose powerful symbolism demolished the conformed traditions of Mannerism, leading art into a new expressive era. Bearer of macabre premonitions, blood is the exclamation mark in two of the most outstanding masterpieces of the early Italian Seicento: Caravaggio's Beheading a/the Baptist (1608)' (fig. 1) and Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith beheading Halo/ernes (1611-12)2 (fig. 2), in which two emblematic events of the Christian tradition are interpreted as a representation of personal memories and fears, generating a powerful spiral of emotions which constantly swirls between fiction and reality. Through this paper I propose that both Caravaggio and Aliemisia adopted blood as a symbolic representation of their own life-stories, understanding it as a vehicle to express intense emotions of fear and revenge. Seen under this perspective, the red fluid results as a powerful and dramatic weapon used to shock the viewer and, at the same time, express an intimate and anguished condition of pain. This so-called Caravaggio, The Beheading of the Baptist, 1608, Co-Cathedral of Saint John, Oratory of Saint John, Valletta, Malta. 2 Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith beheading Halafernes, 1612-13, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples. llO Angelo La Conte 'terrible naturalism'3 symbolically demarks the transition from late Mannerism to early Baroque, introducing art to a new era in which emotions and illusion prevail on rigid and controlled representation. -

Womeninscience.Pdf

Prepared by WITEC March 2015 This document has been prepared and published with the financial support of the European Commission, in the framework of the PROGRESS project “She Decides, You Succeed” JUST/2013/PROG/AG/4889/GE DISCLAIMER This publication has been produced with the financial support of the PROGRESS Programme of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of WITEC (The European Association for Women in Science, Engineering and Technology) and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission. Partners 2 Index 1. CONTENTS 2. FOREWORD5 ...........................................................................................................................................................6 3. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................7 4. PART 1 – THE CASE OF ITALY .......................................................................................................13 4.1 STATE OF PLAY .............................................................................................................................14 4.2 LEGAL FRAMEWORK ...................................................................................................................18 4.3 BARRIERS AND ENABLERS .........................................................................................................19 4.4 BEST PRACTICES .........................................................................................................................20 -

Unemployment Rates in Italy Have Not Recovered from Earlier Economic

The 2017 OECD report The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle explores how gender inequalities persist in social and economic life around the world. Young women in OECD countries have more years of schooling than young men, on average, but women are less still likely to engage in paid work. Gaps widen with age, as motherhood typically has negative effects on women's pay and career advancement. Women are also less likely to be entrepreneurs, and are under-represented in private and public leadership. In the face of these challenges, this report assesses whether (and how) countries are closing gender gaps in education, employment, entrepreneurship, and public life. The report presents a range of statistics on gender gaps, reviews public policies targeting gender inequality, and offers key policy recommendations. Italy has much room to improve in gender equality Unemployment rates in Italy have not recovered from The government has made efforts to support families with earlier economic crises, and Italian women still have one childcare through a voucher system, but regional disparities of the lowest labour force participation rates in the OECD. persist. Improving access to childcare should help more The small number of women in the workforce contributes women enter work, given that Italian women do more than to Italy having one of the lowest gender pay gaps in the three-quarters of all unpaid work (e.g. care for dependents) OECD: those women who do engage in paid work are in the home. Less-educated Italian women with children likely to be better-educated and have a higher earnings face especially high barriers to paid work. -

Italy Women's Rights

October 2019 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE UPR OF ITALY WOMEN’S RIGHTS CONTENTS Context .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Gender stereotypes and discrimination ..................................................................................................... 4 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 5 Violence against women, femicide and firearms ....................................................................................... 4 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 6 VAW: prevention, protection and the need for integrated policies at the national and regional levels . 7 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 7 Violence against women: access to justice ................................................................................................ 8 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 9 Sexual and reproductive health and rights ............................................................................................. 10 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................... -

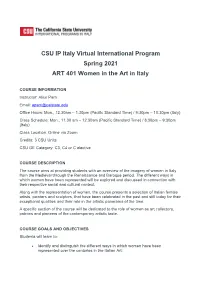

CSU IP Italy Virtual International Program Spring 2021 ART 401

CSU IP Italy Virtual International Program Spring 2021 ART 401 Women in the Art in Italy COURSE INFORMATION Instructor: Alice Parri Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Mon., 12.30am – 1.30pm (Pacific Standard Time) / 9:30pm – 10:30pm (Italy) Class Schedule: Mon., 11.30 am – 12.30am (Pacific Standard Time) / 8:30pm – 9:30pm (Italy) Class Location: Online via Zoom Credits: 3 CSU Units CSU GE Category: C3, C4 or C elective COURSE DESCRIPTION The course aims at providing students with an overview of the imagery of women in Italy from the Medieval through the Renaissance and Baroque period. The different ways in which women have been represented will be explored and discussed in connection with their respective social and cultural context. Along with the representation of women, the course presents a selection of Italian female artists, painters and sculptors, that have been celebrated in the past and still today for their exceptional qualities and their role in the artistic panorama of the time. A specific section of the course will be dedicated to the role of women as art collectors, patrons and pioneers of the contemporary artistic taste. COURSE GOALS AND OBJECTIVES Students will learn to: • Identify and distinguish the different ways in which women have been represented over the centuries in the Italian Art; • Outline the imagery of women in Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque period in connection with specific interpretations, meanings and functions attributed in their respective cultural context; • Recognize and discuss upon the Italian women artists; • Examine and discuss upon the role of Italian women as art collector and patrons. -

Why Are Fertility and Women's Employment Rates So Low in Italy?

IZA DP No. 1274 Why Are Fertility and Women’s Employment Rates So Low in Italy? Lessons from France and the U.K. Daniela Del Boca Silvia Pasqua Chiara Pronzato DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES DISCUSSION PAPER August 2004 Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Why Are Fertility and Women’s Employment Rates So Low in Italy? Lessons from France and the U.K. Daniela Del Boca University of Turin, CHILD and IZA Bonn Silvia Pasqua University of Turin and CHILD Chiara Pronzato University of Turin and CHILD Discussion Paper No. 1274 August 2004 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 Email: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of the institute. Research disseminated by IZA may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit company supported by Deutsche Post World Net. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its research networks, research support, and visitors and doctoral programs. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. -

Annual Report 2000

2000 ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART 2000 ylMMwa/ Copyright © 2001 Board of Trustees, Cover: Rotunda of the West Building. Photograph Details illustrated at section openings: by Robert Shelley National Gallery of Art, Washington. p. 5: Attributed to Jacques Androet Ducerceau I, All rights reserved. The 'Palais Tutelle' near Bordeaux, unknown date, pen Title Page: Charles Sheeler, Classic Landscape, 1931, and brown ink with brown wash, Ailsa Mellon oil on canvas, 63.5 x 81.9 cm, Collection of Mr. and Bruce Fund, 1971.46.1 This publication was produced by the Mrs. Barney A. Ebsworth, 2000.39.2 p. 7: Thomas Cole, Temple of Juno, Argrigentum, 1842, Editors Office, National Gallery of Art Photographic credits: Works in the collection of the graphite and white chalk on gray paper, John Davis Editor-in-Chief, Judy Metro National Gallery of Art have been photographed by Hatch Collection, Avalon Fund, 1981.4.3 Production Manager, Chris Vogel the department of photography and digital imaging. p. 9: Giovanni Paolo Panini, Interior of Saint Peter's Managing Editor, Tarn Curry Bryfogle Other photographs are by Robert Shelley (pages 12, Rome, c. 1754, oil on canvas, Ailsa Mellon Bruce 18, 22-23, 26, 70, 86, and 96). Fund, 1968.13.2 Editorial Assistant, Mariah Shay p. 13: Thomas Malton, Milsom Street in Bath, 1784, pen and gray and black ink with gray wash and Designed by Susan Lehmann, watercolor over graphite, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Washington, DC 1992.96.1 Printed by Schneidereith and Sons, p. 17: Christoffel Jegher after Sir Peter Paul Rubens, Baltimore, Maryland The Garden of Love, c. -

OECD EMPLOYMENT OUTLOOK – ISBN 92-64-19778-8 – ©2002 62 – Women at Work: Who Are They and How Are They Faring?

Chapter 2 Women at work: who are they and how are they faring? This chapter analyses the diverse labour market experiences of women in OECD countries using comparable and detailed data on the structure of employment and earnings by gender. It begins by documenting the evolution of the gender gap in employment rates, taking account of differences in working time and how women’s participation in paid employment varies with age, education and family situation. Gender differences in occupation and sector of employment, as well as in pay, are then analysed for wage and salary workers. Despite the sometimes strong employment gains of women in recent decades, a substantial employment gap remains in many OECD countries. Occupational and sectoral segmentation also remains strong and appears to result in an under-utilisation of women’s cognitive and leadership skills. Women continue to earn less than men, even after controlling for characteristics thought to influence productivity. The gender gap in employment is smaller in countries where less educated women are more integrated into the labour market, but occupational segmentation tends to be greater and the aggregate pay gap larger. Less educated women and mothers of two or more children are considerably less likely to be in employment than are women with a tertiary qualification or without children. Once in employment, these women are more concentrated in a few, female-dominated occupations. In most countries, there is no evidence of a wage penalty attached to motherhood, but their total earnings are considerably lower than those of childless women, because mothers more often work part time. -

The Female Condition During Mussolini's and Salazar's Regimes

The Female Condition During Mussolini’s and Salazar’s Regimes: How Official Political Discourses Defined Gender Politics and How the Writers Alba de Céspedes and Maria Archer Intersected, Mirrored and Contested Women’s Role in Italian and Portuguese Society Mariya Ivanova Chokova Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Prerequisite for Honors In Italian Studies April 2013 Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………4 Chapter I: The Italian Case – a historical overview of Mussolini’s gender politics and its ideological ramifications…………………………………………………………………………..6 I. 1. History of Ideology or Ideology of History……………………………………………7 1.1. Mussolini’s personal charisma and the “rape of the masses”…………………………….7 1.2. Patriarchal residues in the psychology of Italians: misogyny as a trait deeply embedded, over the centuries, in the (sub)conscience of European cultures……………………………...8 1.3. Fascism’s role in the development and perpetuation of a social model in which women were necessarily ascribed to a subaltern position……………………………………………10 1.4. A pressing need for a misogynistic gender politics? The post-war demographic crisis and the Role of the Catholic Church……………………………………………………………..12 1.5. The Duce comes in with an iron fist…………………………………………………….15 1.6. Fascist gender ideology and the inconsistencies and controversies within its logic…….22 Chapter II: The Portuguese Case – Salazar’s vision of woman’s role in Portuguese society………………………………………………………………………………………..28 II. 2.1. Gender ideology in Salazar’s Portugal.......................................................................29 2.2. The 1933 Constitution and the social place it ascribed to Portuguese women………….30 2.3. The role of the Catholic Church in the construction and justification of the New State’s gender ideology: the Vatican and Lisbon at a crossroads……………………………………31 2 2.4. -

Profiling Women in Sixteenth-Century Italian

BEAUTY, POWER, PROPAGANDA, AND CELEBRATION: PROFILING WOMEN IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY ITALIAN COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS by CHRISTINE CHIORIAN WOLKEN Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Edward Olszewski Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERISTY August, 2012 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Christine Chiorian Wolken _______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy Candidate for the __________________________________________ degree*. Edward J. Olszewski (signed) _________________________________________________________ (Chair of the Committee) Catherine Scallen __________________________________________________________________ Jon Seydl __________________________________________________________________ Holly Witchey __________________________________________________________________ April 2, 2012 (date)_______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 1 To my children, Sofia, Juliet, and Edward 2 Table of Contents List of Images ……………………………………………………………………..….4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………...…..12 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………...15 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 1: Situating Sixteenth-Century Medals of Women: the history, production techniques and stylistic developments in the medal………...44 Chapter 2: Expressing the Link between Beauty and -

Are Foreign Women Competitive in the Marriage Market? Evidence from a New Immigration Country

Are Foreign Women Competitive in the Marriage Market? Evidence from a New Immigration Country Daniele Vignoli1,2 – Alessandra Venturini2,3 – Elena Pirani1 1University of Florence 2 Migration Policy Centre – European University Institute 3University of Torino Short paper prepared for the 2015 PAA Annual Meeting, San Diego, California, April 30 – May 2. This is only an initial draft – Please do not quote or circulate ABSTRACT Whereas empirical studies concentrating on individual-level determinants of marital disruption have a long tradition, the impact of contextual-level determinants is much less studied. In this paper we advance the hypothesis that the size (and the composition) of the presence of foreign women in a certain area affect the dissolution risk of established marriages. Using data from the 2009 survey Family and Social Subjects, we estimate a set of multilevel discrete-time event history models to study the de facto separation of Italian marriages. Aggregate-level indicators, referring to the level and composition of migration, are our main explanatory variables. We find that while foreign women are complementary to Italian women within the labor market, the increasing presence of first mover’s foreign women (especially coming from Latin America and some countries of Eastern Europe) is associated with elevated separation risks. These results proved to be robust to migration data stemming from different sources. 1 1. Motivation Europe has witnessed a substantial increase in the incidence of marital disruption in recent decades. This process is most advanced in Nordic countries, where more than half of marriages ends in divorce, followed by Western, and Central and Eastern European countries (Sobotka and Toulemon 2008; Prskawetz et al.