Kazan Gateway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Programme

FINAL PROGRAMME Friday, 12 June 2015 8.00-9.00 Registration 9.00-9.30 Welcome Address/Opening ceremony Chairs: S. Cicėnas (Vilnius, Lithuania) Minister of health of the Republic of Lithuania (Vilnius, Lithuania) Rector of Vilnius University (Vilnius, Lithuania) Dean of the Faculty of Medicine Vilnius University (Vilnius, Lithuania) Director of the Nacional Cancer Institute (Vilnius, Lithuania) 9.30 – 11.00 SESSION I Chairs: J. Niklinski (Bialystok, Poland), K. Sužiedėlis (Vilnius, Lithuania) 9.30-11.00 Bialystok Medical Academy – Research Group (Bialystok, Poland) Chairs: Prof. Jacek Niklinski, Prof. Lech Chyczewski Immune system and lung cancer: friends or foes? M. Moniuszko Science fiction or science reality - microRNA replacement therapy Anna Rusek The role of transcription factor Sox2 in cancer biology A. Eljaszewicz Recent guidelines for the diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer- diagnostic challenges and problems J. Reszec Metabolomic profiling of non-small cell lung cancer J. Kisluk 11.00 - 11.30 Lung cancer in women and never smokers S. Novello (Turin, Italy) 11.30 - 12.00 Coffee break 12.00 –13.00 AstraZeneca Satellite Symposium Chair: S. Cicėnas (Vilnius, Lithuania) 13.00-14.00 Lunch 14.00 – 16.40 Scientific session II Chairs: R. Pirker (Vienna, Austria), E. Danila (Vilnius, Lithuania). 14.00-14.40 Bevacizumab in treatment of NSCLC: preferred chemo partners F. De Marinis (Milan, Italy) 14.40-15.00 Lung Cancer Screening – Radiological Opportunities and Challenges S. Sudarski (Mannheim, Germany) 15.00-15.20 Tobacco control strategies M. Neuberger (Vienna, Austria) 15.20-15.40 Lung cancer screening by spiral CT M. Silva (Milano, Italy) 15.40-16.00 Biomarkers for chemotherapy in NSCLC J.B. -

RZD Logistics JSC RZD LOGISTICS at a GLANCE

RZD Logistics JSC RZD LOGISTICS AT A GLANCE >30 branch offices and separate RUSSIA’S LARGEST subdivisions logistics company Representatives of RZD Logistics Nuremberg Milan Subsidiaries in China and Europe Prague Warsaw Riga 160 170 Ust-Luga Vienna departure destination St. Petersburg cities cities Moscow Yaroslavl Sosnogorsk Kirov N. Novgorod Perm N. Tagil Nikolskoe Pyt’-Yakh Voronezh Krasny Sulin Yelabuga ≈ Balakovo Yekaterinburg >680 1000 Samara Tomsk Krasnoyarsk partners employees Saratov Khabarovsk Rostov-on-Don Novosibirsk Zabaikalsk Irkutsk Vladivostok Novokuznenetsk Vostochny Biysk Manzhouli Changchun Yingkou 50 ≈ 600 Beijing mln tons standardized of processed routes cargo per year Suzhou Shanghai THE LARGEST 36 TAXPAYER bln rubles revenue in 2019 Chongqing 2 CONTAINER SHIPPING OUR ADVANTAGES All services on the basis One-stop shopping service of one application Special rates for direct High speed delivery Transit railway services at the optimal price Export/import Delivery across Multimodal shipments Optimal price-quality ratio Russia, CIS Scheduled trains Just-in-time delivery "First/last" mile "Door-to-door" delivery Prompt informing Transparency on cargo dislocation of delivery process Insurance Cargo safety Procedures "export", "import", Customs clearance "temporary import" Document support Correct transport and shipping documentation Shipping of cargo weighing more than 20 kg LCL shipping 4 OUR CONTAINER ROUTES Gent Antwerp Rotterdam Wilhelmshaven Lübeck Duisburg Hamburg Helsinki Milan Gdynia Warsaw St. Petersburg Lodz Małaszewicze -

The Dynamic Gravity Dataset: Technical Documentation

The Dynamic Gravity Dataset: Technical Documentation Lead Authors:∗ Tamara Gurevich and Peter Herman Contributing Authors: Nabil Abbyad, Meryem Demirkaya, Austin Drenski, Jeffrey Horowitz, and Grace Kenneally Version 1.00 Abstract This document provides technical documentation for the Dynamic Gravity dataset. The Dynamic Gravity dataset provides extensive country and country pair information for a total of 285 countries and territories, annually, between the years 1948 to 2016. This documentation extensively describes the methodology used for the creation of each variable and the information sources they are based on. Additionally, it provides a large collection of summary statistics to aid in the understanding of the resulting Dynamic Gravity dataset. This documentation is the result of ongoing professional research of USITC Staff and is solely meant to represent the opinions and professional research of individual authors. It is not meant to represent in any way the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission or any of its individual Commissioners. It is circulated to promote the active exchange of ideas between USITC Staff and recognized experts outside the USITC, professional devel- opment of Office Staff and increase data transparency by encouraging outside professional critique of staff research. Please address all correspondence to [email protected] or [email protected]. ∗We thank Renato Barreda, Fernando Gracia, Nuhami Mandefro, and Richard Nugent for research assistance in completion of this project. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Nomenclature . .3 1.2 Variables Included in the Dataset . .3 1.3 Contents of the Documentation . .6 2 Country or Territory and Year Identifiers 6 2.1 Record Identifiers . -

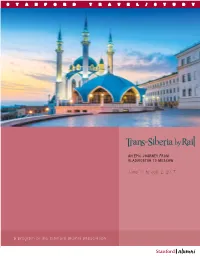

June 16 to July 2, 2017 a Program of the Stanford Alumni Association

STANFORD TRAVEL/STUDY STANFORD TRAVEL/STUDY AN EPIC JOURNEY FROM VLADIVOSTOK TO MOSCOW June 16 to July 2, 2017 a program of the stanford alumni association STANFORD TRAVEL/STUDY Get ready for the ride of your life on this epic, 6,000-mile-long journey aboard the luxurious, modern Golden Eagle Trans-Siberian Express train, traversing the world’s largest country—from her deepwater Pacific seaport of Vladivostok to her cosmopolitan capital, Moscow. We’ll travel through endless miles of Siberian taiga (subarctic evergreen forest); dip down onto the vast Mongolian steppe; view Lake Baikal, the world’s largest body of fresh water; visit the majestic kremlin in the exotic city of Kazan; and end our incredible journey marveling at the iconic façade of St. Basil’s Cathedral on Red Square in Moscow. Along the way, we’ll delve into Russia’s long history, fascinating cultures, politics and economy, and meet her modern-day peoples. All aboard for a fabulous adventure! BREtt S. THompson, ’83, DirEctor, Stanford TravEL/StudY ST. BASIL’S CATHEDRAL, Moscow Highlights LISTEN to the UNESCO- EXPLORE the kremlin of ENJOY a private concert RIDE in modern comfort recognized 17th-century Kazan, capital of Tatarstan, and champagne reception on the tracks of the czarist- songs of Russia’s Old with its mix of Orthodox in Irkutsk at the Decembrist era Old Railway line along Believers in a village near churches and Muslim House-Museum, home the shore of Lake Baikal, Ulan Ude. mosques. of a once-imprisoned the world’s deepest and Decembrist activist. oldest freshwater lake. -

The Rev. Dr. Robert M. Roegner

RLCMussiaS WORLD MISSIONandTOUR the Baltics May 22 - June 4, 2007 Hosted by The Rev. Dr. Robert & Kristi Roegner The Rev. Dr. William & Carol Diekelman The Rev. Brent & Jennie Smith 3 o c s o M , n i l m e r K e h t n a e r a u - S e R Dear Friends o. LCMS World Mission, One never knoIs Ihere and Ihen od Iill open a door for the ood NeIs of Jesus. /ith the fall of the Iron Curtain, od opened a door of huge opportunity in Russia and Eastern Europe. ,he collapse of European Communism also brought us in touch--and in partnership--Iith felloI Lutherans Iho by od's grace had remained steadfast in the faith through decades of persecuMOSCOWtion. ,oday, LCMS /orld Mission and its partners are AblaLe! as Ie seek to share the ospel Iith 100 million unreached or uncommitted people IorldIide by 2017, the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. I invite you to join me and my Iife, $risti, and LCMS First .ice President Bill Diekelman and his Iife, Carol, on a very special AblaLe! tour of Russia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Joining and guiding us Iill be LCMS /orld Mission's Eurasia regional director, Rev. Brent Smith, and his STIife, Jennie. PETERSBURG Not only Iill Ie visit some of the Iorld's most famous, historic, and grand sites, but you Iill have the rare opportunity to meet Iith LCMS missionaries and felloI Lutherans from our partner churches for a first-hand look at hoI od is using them to proclaim the ospel in a region once closed to us. -

Boat Accident

DREF operation final report Russian Federation: Boat Accident DREF operation n° MDRRU012 GLIDE n° AC-2011-000086-RUS 12th April 2012 The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross Red Crescent response to emergencies. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of National Societies to respond to disasters. Summary: The cruise ship “Bulgaria” was caught in a storm on the Volga river in Tatarstan on Sunday, 10th July 2011, at about 14.00 and sank within minutes at one of the widest points of the river claiming the lives of 130 people. The Russian Red Cross provided psychosocial support to the affected families of the deceased and to the survivors in order to minimize the psychological effects in the aftermath of the boat accident. Most of the victims are Survivors of "Bulgaria" resqued by "Arabella" cruiser ship are brought ashore residents of Tatarstan. This Photo: Reuters operation was implemented over six months and was completed by the 15th January 2012. CHF 25,358 was allocated from the International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the Russian Red Cross in delivering immediate psychosocial assistance to some 200 families. Following the implementation of the operation, there is a balance of CHF 911 that needs to be returned to the DREF funds. The -

Turkological and Ottomanic Legacy of Ay Krymsky and Oriental Studies in Russia

COMPETITIVE STRATEGY MODEL AND ITS IMPACT ON MICRO BUSINESS UNIT OF LOCAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS IN JAWA PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020) TURKOLOGICAL AND OTTOMANIC LEGACY OF A.Y. KRYMSKY AND ORIENTAL STUDIES IN RUSSIA (1896 – 1941) Ramil M. Valeev1, Roza Z. Valeeva2, Dinar R. Khayrutdinov3,Oksana D. Vasylyuk4 1Department of Altaic and Chinese Studies, Institute of International Relations, Kazan (Volga Region) Federal University – Kazan, Russia 2Department of International Languages and Translation Studies, V. G. Timiryasov Kazan Innovative University – Kazan, Russia 3Department of International Languages and Translation Studies, V. G. Timiryasov Kazan Innovative University – Kazan, Russia 4A. Krymsky Institute of Oriental Studies, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine – Kiev, Ukraine [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Klemi Subiyantoro,Ina Primiana Sagir,Aldrin Herwany,Rie Febrian. Competitive Strategy Model And Its Impact On Micro Business Unit Of Local Development Banks In Jawa-- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(4), 470-484. ISSN 1567-214x Keywords:Russia, Ukraine, the East, Turkic peoples, A.Y. Krymsky, Turkology, Ottoman studies, Turkic and Ottoman literature, history, language. ABSTRACT: Research of the Turkic (including Asia Minor), social-political, cultural and ethnolinguistic space of Eurasia is a significant and long-standing tradition of practical and academic research centers of Russia and Europe, including Ukraine. The Turkic (including Ottoman) political and cultural -

THE NATURAL RADIOACTIVITY of the BIOSPHERE (Prirodnaya Radioaktivnost' Iosfery)

XA04N2887 INIS-XA-N--259 L.A. Pertsov TRANSLATED FROM RUSSIAN Published for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and the National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. by the Israel Program for Scientific Translations L. A. PERTSOV THE NATURAL RADIOACTIVITY OF THE BIOSPHERE (Prirodnaya Radioaktivnost' iosfery) Atomizdat NMoskva 1964 Translated from Russian Israel Program for Scientific Translations Jerusalem 1967 18 02 AEC-tr- 6714 Published Pursuant to an Agreement with THE U. S. ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION and THE NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION, WASHINGTON, D. C. Copyright (D 1967 Israel Program for scientific Translations Ltd. IPST Cat. No. 1802 Translated and Edited by IPST Staff Printed in Jerusalem by S. Monison Available from the U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Clearinghouse for Federal Scientific and Technical Information Springfield, Va. 22151 VI/ Table of Contents Introduction .1..................... Bibliography ...................................... 5 Chapter 1. GENESIS OF THE NATURAL RADIOACTIVITY OF THE BIOSPHERE ......................... 6 § Some historical problems...................... 6 § 2. Formation of natural radioactive isotopes of the earth ..... 7 §3. Radioactive isotope creation by cosmic radiation. ....... 11 §4. Distribution of radioactive isotopes in the earth ........ 12 § 5. The spread of radioactive isotopes over the earth's surface. ................................. 16 § 6. The cycle of natural radioactive isotopes in the biosphere. ................................ 18 Bibliography ................ .................. 22 Chapter 2. PHYSICAL AND BIOCHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF NATURAL RADIOACTIVE ISOTOPES. ........... 24 § 1. The contribution of individual radioactive isotopes to the total radioactivity of the biosphere. ............... 24 § 2. Properties of radioactive isotopes not belonging to radio- active families . ............ I............ 27 § 3. Properties of radioactive isotopes of the radioactive families. ................................ 38 § 4. Properties of radioactive isotopes of rare-earth elements . -

Kazan Kremlin (Russian Federation) No

Category of property Kazan Kremlin (Russian Federation) In terms of the categories of cultural property set out in Article 1 of the 1972 World Heritage Convention, this is a group of buildings. No 980 History and Description History The first human occupation in the Kazan area goes back to Identification the 7th and 8th millennia BCE; there are traces of the Bronze Age (2nd to 1st millennia, late Kazan area settlement), early Nomination Historical and Architectural Complex of Iron Age (8th to 6th centuries BCE, Ananin culture), and the Kazan Kremlin early medieval period (4th–5th centuries CE, Azelin culture). From the 10th to 13th centuries Kazan was a pre-Mongol Location Republic of Tatarstan, City of Kazan Bulgar town. Today’s Kremlin hill consisted then of a fortified trading settlement surrounded by moats, State Party Russian Federation embankments, and a stockade. A stone fortress was built in the 12th century and the town developed as an outpost on the Date 29 June 1999 northern border of Volga Bulgaria. The so-called Old Town extended eastward, on the site of the former Kazan Monastery of Our Lady. The fortress was demolished on the instructions of the Mongols in the 13th century. A citadel was then built as the seat of the Prince of Kazan, including the town’s administrative and religious institutions. By the Justification by State Party first half of the 15th century, the town had become the capital The Kazan Kremlin is a unique and complex monument of of the Muslim Principality of Bulgaria, with administrative, archaeology, history, urban development, and architecture. -

Key Facts 2019 Messe Düsseldorf Group

07/2020 EN KEY FACTS 2019 MESSE DÜSSELDORF GROUP www.messe-duesseldorf.com umd2002_00149.indd 3 27.07.20 13:38 CONTENTS 2015–2019 - An overview 04 Business trends 06 Events in Düsseldorf in 2019 08 Areas of expertise 10 International flair 12 Messe Düsseldorf Group 14 Foreign markets 16 Markets & locations 18 Global product portfolios 20 Bodies 24 Düsseldorf as a trade fair location 26 Site plan 28 Keeping in touch & news 30 02 03 umd2002_00149.indd 4 umd2002_00149.indd27.07.20 13:38 5 27.07.20 13:38 2015-2019 – AN OVERVIEW BUSINESS TRENDS 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Total capacity * m2 304,800 304,800 291,580 291,580 305,727 ° Hall space available m2 261,800 261,800 248,580 248,580 262,727 ° Open-air space available m2 43,000 43,000 43,000 43,000 43,000 Space utilized * m2 (gross) 1,624,789 2,247,486 1,858,831 1,618,357 1,701,618 Space rented out * m2 (net) 891,438 1,308,304 1,162,415 948,782 1,014,145 Fairs and exhibitions * Total 29 31 31 26 29 Self-organized events * 18 19 18 15 18 Partner/guest events * 11 12 13 11 11 Total consolidated sales € million 302.0 442.8 366.9 294.0 378.5 Consolidated sales (Germany) € million 202.1 369.7 302.1 222.6 308.4 Consolidated sales (foreign) € million 99.9 73.1 64.8 71.4 70.1 Consolidated annual profit € million 10.3 58.8 55.0 24.3 56.6 Group workforce 1,207 932 831 831 860 Exhibitors * Total 25,819 32,383 29,210 26,827 29,222 Exhibitors (German-based) 9,189 10,796 9,579 8,462 8,940 Exhibitors (foreign-based) 16,630 21,587 19,631 18,401 20,282 Visitors * Total 1,084,121 1,591,424 1,344,548 1,125,187 1,373,780 Visitors from Germany 802,291 899,322 857,739 782,119 869,458 Visitors from abroad 281,830 692,102 486,809 342,878 504,322 Düsseldorf Congress GmbH Event days 314 308 303 277 240 Events 3,463 3,695 3,461 2,197 1,277 ** Participants 2,355,149 2,269,494 2,508,083 1,632,448 373,490 ** * Düsseldorf exhibition site – due to differences in the numbers of events, the annual figures are only partly comparable. -

Án Zimonyi, Medieval Nomads in Eastern Europe

As promised, after the appearance of Crusaders, in Slavic or Balkan languages, or Russian authors Missionaries and Eurasian Nomads in the 13th who confine themselves to bibliography in their 14th Centuries: A Century of Interaction, Hautala own mother tongue,” Hautala’s linguistic capabili did indeed publish an anthology of annotated ties enabled him to become conversant with the Russian translations of the Latin texts.10 In his in entire field of Mongol studies (14), for which all troduction, Spinei observes that “unlike WestEu specialists in the Mongols, and indeed all me ropean authors who often ignore works published dievalists, should be grateful. 10 Ot “Davida, tsaria Indii” do “nenavistnogo plebsa satany”: Charles J. Halperin antologiia rannikh latinskikh svedenii o tataromongolakh (Kazan’: Mardzhani institut AN RT, 2018). ——— István Zimonyi. Medieval Nomads in Eastern Part I, “Volga Bulgars,” the subject of Zimonyi’s Europe: Collected Studies. Ed. Victor Spinei. Englishlanguage monograph,1 contains eight arti Bucureşti: Editoru Academiei Romăne, Brăila: cles. In “The First Mongol Raids against the Volga Editura Istros a Muzueului Brăilei, 2014. 298 Bulgars” (1523), Zimonyi confirms the report of pp. Abbreviations. ibnAthir that the Mongols, after defeating the his anthology by the distinguished Hungarian Kipchaks and the Rus’ in 1223, were themselves de Tscholar of the University of Szeged István Zi feated by the Volga Bolgars, whose triumph lasted monyi contains twentyeight articles, twentyseven only until 1236, when the Mongols crushed Volga of them previously published between 1985 and Bolgar resistance. 2013. Seventeen are in English, six in Russian, four In “Volga Bulgars between Wind and Water (1220 in German, and one in French, demonstrating his 1236)” (2533), Zimonyi explores the preconquest adherence to his own maxim that without transla period of BulgarMongol relations further. -

Black Sea-Caspian Steppe: Natural Conditions 20 1.1 the Great Steppe

The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editors Florin Curta and Dušan Zupka volume 74 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ecee The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe By Aleksander Paroń Translated by Thomas Anessi LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Publication of the presented monograph has been subsidized by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education within the National Programme for the Development of Humanities, Modul Universalia 2.1. Research grant no. 0046/NPRH/H21/84/2017. National Programme for the Development of Humanities Cover illustration: Pechenegs slaughter prince Sviatoslav Igorevich and his “Scythians”. The Madrid manuscript of the Synopsis of Histories by John Skylitzes. Miniature 445, 175r, top. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Proofreading by Philip E. Steele The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://catalog.loc.gov/2021015848 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”.