The Decline of European Sea Power Europe's Navies in a Time of Austerity and Brinkmanship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Future Technology and International Cooperation a UK Perspective

MAY Future Technology and International Cooperation A UK perspective In 2011, NATO’s Integrated Air Defence (NATINAD) and the supporting NATO Integrated Air Defence System (NATINADS) marked 50 years of safeguarding NATO’s skies. In order to successfully reach future milestones NATO must continue (and in many cases improve) its air defence interoperability across the strategic, operational and tactical domains. In order for this to become reality a combination of exploiting synergies and acknowledging that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts1 is required at all levels. Recent improvements and a greater focus on future capability within the UK’s Joint Ground Based Air Defence (Jt GBAD) will enable the Formation to deploy its units and sub-units in order to operate the latest air defence weapon systems, within a multinational environment, against a near-peer adversary or asymmetric threat, and win. Major Charles W.I. May RA – 14 (Cole’s Kop) Battery Royal Artillery* the strategic direction of the British Armed ‘If I didn‘t have air supremacy, I wouldn‘t be here.’ Forces, and subsequently the operational level (SACEUR, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, June 1944) construct. As the new direction is towards Joint Force 2025 (JF2025) it is pragmatic for this paper to focus on the next 10 years. The his article will highlight the UK military’s purpose is to identify and highlight the Tstrategic situation, perception and under- pertinent capability enhancements and future standing of the air threat before explaining the vision of the UK’s Ground Based Air Defence new military structure to which the Formation Formation and its developing role within the is adapting. -

Mt-2018-2-3.Pdf

2–3/2018 Kr 48,- TIDSAM 1098-02 NORWEGIAN DEFENCE And ECURITY ndUSTRIES ssOCIATION 9 770806 615906 02 S I A RETURUKEReturuke 39 v 12 STYRETS ÅRSBERETNING 2017 GiraffeFlexible protection for mobile forces1X Saab Technologies Norway AS saab.no CONTENTS CONTENTS: MINE CLEARANCE Editor-in-Chief: 2 The future is unmanned M.Sc. Bjørn Domaas Josefsen NSM 6 US Navy selects Naval Strike Missile NORDIC DEFENCE CO- OPERATION; NOT NECESSARILY DOOMED TO FAILURE NORDEFCO 8 NDIS (Nordic Defence Industry Seminar) 2018 Nordic collaboration within the defence sector has for many years been riddled with good intentions, but often with meagre results to show for all the efforts. FSi The Nordic countries are often regarded as a common unit, with 11 Norwegian Defence and Security almost similar languages (except Finland), a great deal of cultural Industries Association (FSi) similarity, and a long-standing tradition for co-operation on a number of different arenas. And yet, there are significant differences between the countries, not 17 ÅRSRAPPORT 2017 least from a security political and military point of view. Two of the Nordic countries are members of NATO, while two are BULLETIN BOARD FOR DEFENCE, alliance-free. Finland has an extended land border to Russia, while INDUSTRY AND TRADE Norway has a short land border as well as a long demarcation line at sea. Neither Sweden nor Denmark have land borders to Russia. 59 Gripen Plant in Brazil Sweden and Finland have huge forest regions, where Norway has 61 Command post shelters for Kongsberg fjords, mountains and deep valleys; Denmark mainly consists of a flat 63 Training Systems for the Swedish Army culture landscape spread across some mainland and a few large islands. -

Alternative Naval Force Structure

Alternative Naval Force Structure A compendium by CIMSEC Articles By Steve Wills · Javier Gonzalez · Tom Meyer · Bob Hein · Eric Beaty Chuck Hill · Jan Musil · Wayne P. Hughes Jr. Edited By Dmitry Filipoff · David Van Dyk · John Stryker 1 Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................ 3 The Perils of Alternative Force Structure ................................................... 4 By Steve Wills UnmannedCentric Force Structure ............................................................... 8 By Javier Gonzalez Proposing A Modern High Speed Transport – The Long Range Patrol Vessel ................................................................................................... 11 By Tom Meyer No Time To Spare: Drawing on History to Inspire Capability Innovation in Today’s Navy ................................................................................. 15 By Bob Hein Enhancing Existing Force Structure by Optimizing Maritime Service Specialization .............................................................................................. 18 By Eric Beaty Augment Naval Force Structure By Upgunning The Coast Guard .......................................................................................................... 21 By Chuck Hill A Fleet Plan for 2045: The Navy the U.S. Ought to be Building ..... 25 By Jan Musil Closing Remarks on Changing Naval Force Structure ....................... 31 By Wayne P. Hughes Jr. CIMSEC 22 www.cimsec.org -

Security & Defence European

a 7.90 D European & Security ES & Defence 4/2016 International Security and Defence Journal Protected Logistic Vehicles ISSN 1617-7983 • www.euro-sd.com • Naval Propulsion South Africa‘s Defence Exports Navies and shipbuilders are shifting to hybrid The South African defence industry has a remarkable breadth of capa- and integrated electric concepts. bilities and an even more remarkable depth in certain technologies. August 2016 Jamie Shea: NATO‘s Warsaw Summit Politics · Armed Forces · Procurement · Technology The backbone of every strong troop. Mercedes-Benz Defence Vehicles. When your mission is clear. When there’s no road for miles around. And when you need to give all you’ve got, your equipment needs to be the best. At times like these, we’re right by your side. Mercedes-Benz Defence Vehicles: armoured, highly capable off-road and logistics vehicles with payloads ranging from 0.5 to 110 t. Mobilising safety and efficiency: www.mercedes-benz.com/defence-vehicles Editorial EU Put to the Test What had long been regarded as inconceiv- The second main argument of the Brexit able became a reality on the morning of 23 campaigners was less about a “democratic June 2016. The British voted to leave the sense of citizenship” than of material self- European Union. The majority that voted for interest. Despite all the exception rulings "Brexit", at just over 52 percent, was slim, granted, the United Kingdom is among and a great deal smaller than the 67 percent the net contribution payers in the EU. This who voted to stay in the then EEC in 1975, money, it was suggested, could be put to but ignoring the majority vote is impossible. -

Operation Kipion: Royal Navy Assets in the Persian by Claire Mills Gulf

BRIEFING PAPER Number 8628, 6 January 2020 Operation Kipion: Royal Navy assets in the Persian By Claire Mills Gulf 1. Historical presence: the Armilla Patrol The UK has maintained a permanent naval presence in the Gulf region since October 1980, when the Armilla Patrol was established to ensure the safety of British entitled merchant ships operating in the region during the Iran-Iraq conflict. Initially the Royal Navy’s presence was focused solely in the Gulf of Oman. However, as the conflict wore on both nations began attacking each other’s oil facilities and oil tankers bound for their respective ports, in what became known as the “tanker war” (1984-1988). Kuwaiti vessels carrying Iraqi oil were particularly susceptible to Iranian attack and foreign-flagged merchant vessels were often caught in the crossfire.1 In response to a number of incidents involving British registered vessels, in October 1986 the Royal Navy began accompanying British-registered vessels through the Straits of Hormuz and in the Persian Gulf. Later the UK’s Armilla Patrol contributed to the Multinational Interception Force (MIF), a naval contingent patrolling the Persian Gulf to enforce the UN-mandated trade embargo against Iraq, imposed after its invasion of Kuwait in August1990.2 In the aftermath of the 2003 Iraq conflict, Royal Navy vessels, deployed as part of the Armilla Patrol, were heavily committed to providing maritime security in the region, the protection of Iraq’s oil infrastructure and to assisting in the training of Iraqi sailors and marines. 1.1 Assets The Type 42 destroyer HMS Coventry was the first vessel to be deployed as part of the Armilla Patrol, followed by RFA Olwen. -

Ministry of Defence: Design and Procurement of Warships

NATIONAL AUDIT OFFICE Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General Ministry of Defence: Design and Procurement of Warships Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 5 June 1985 LONDON HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE E3.30 net 423 This report is presented to the House of Commons in accordance with Section 9 of the National Audit Act, 1983. Gordon Downey Comljtroller and Auditor General National Audit Office 4 June 1985 Contents Ministry of Defence: Design and Procurement of Warships Pages Summary and conclusions l-5 Report Part 1: Background 6 Part 2: Division of Responsibilities for Warshipbuilding 7-8 Part 3: Effectiveness of MOD’s Design and Development Arrangements 9-12 Part 4: Performance of Warshipbuilders 13-15 Part 5: Negotiation of Warship Contracts 16-17 Glossary of abbreviations 18 Appendix Mr Levene’s recommendations on warship procurement 19 Ministry of Defence: Design and Procurement of Warships Summary and conclusions 1. This Report records the results of an examination by the National Audit Office (NAO) of the Ministry of Defence (MOD)‘s arrangements for design and procurement of warships. It covers the progress made in increasing warshipbuil- ders’ involvement in and responsibility for design; the difficulties encountered in design and development of new ships; and MOD’s influence on the performance and productivity of the warshipbuilders and the effect of the latter on the achieve- ment of value for money. These matters have all been the subject of earlier Reports by the Public Accounts Committee (PAC). I intend to provide PAC with further details to supplement this Report, on a confidential basis. -

“Emphasize Versatility”

2012 Tuesday, October 23 / Mardi 23 octobre NEWSNEWS 1 NAVAL DEFENSE AND MARITIME EXHIBITION AND CONFERENCE Bilingual edition “EMPHASIZE Édition bilingue VERSATILITY” Interview with Admiral Bernard Rogel, Chief of Sta of the French Navy Admiral, what will the 2012 Euronaval SMX26 the future show mean for the French Navy? of submarine The French Marine nationale is going coastal operations through a pivotal period in its history. On the one hand, the challenges at sea are Le SMX26, le futur des having an increasingly decisive e ect on opérations sous-marines our country’s economy. I’m referring to the côtières. phenomenon of “maritimization”—the twin PAGE 14 sister of globalization. Secondly, our naval defense tools are going through a major upgrade: the gradual introduction of the FREMM multipurpose frigate, and a step- EXCLUSIVE ping up of the Barracuda programs and overseas support ships in particular. The INTERVIEW question is how we will be using these new Entretien exclusif tools in the present context. The Euronaval (© Alain Monot / Marine Nationale) 2012 event will be an excellent opportunity The issue of European industrial coopera- Admiral Sir Mark Stanhope, to discuss this subject with our industry part- tion in the naval area is a hot topic. What FIRST SEA LORD and ners and my counterparts in other navies. is your view on this? What are your expec- Royal Navy chief of tations? naval sta What will you be looking for specifically? This cooperation is essential. Today, we Which presentations will most attract your must create economies of scale, conside- PAGE 5 attention this year in particular? ring the reduction in European countries’ In Toulon we had the opportunity to visit our defense budgets and the competition of new ships: BPC, the Horizon frigate, EDA-R, export markets. -

GAO WEAPONS ACQUISITION Precision Guided Munitions In

United States General Accounting Office GAO Report to Congressional Committees June 1995 WEAPONS ACQUISITION Precision Guided Munitions in Inventory, Production, and Development GAO/NSIAD-95-95 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 National Security and International Affairs Division B-260458 June 23, 1995 Congressional Committees The military services are spending billions of dollars to acquire new and improved munitions whose technical sophistication allows guidance corrections during their flight to the target. These weapons are referred to as precision guided munitions (PGM). We reviewed Air Force, Navy, and Army munitions programs in inventory, production, and development that could be defined as using precision guidance to attack surface targets.1 Our objectives were to determine (1) the costs and quantities planned for the PGMs, (2) the services rationale for initiating PGM development programs, (3) options available to the services to attack surface targets with PGMs, and (4) the extent to which the services are jointly developing and procuring PGMs. We conducted this work under our basic legislative responsibilities and plan to use this baseline report in planning future work on Defense-wide issues affecting the acquisition and effectiveness of PGMs. We are addressing the report to you because we believe it will be of interest to your committees. PGMs employ various guidance methods to enhance the probability of Background hitting the target. These include target location information from a human designator, global positioning system (GPS) satellites, an inertial navigation system, a terminal seeker on the munition, or a combination of these sources. Since PGMs can correct errors in flight, the services expect to need fewer rounds to achieve the same or higher probabilities of kill as unguided weapons. -

Commercially Available Low Probability of Intercept Radars and Non-Cooperative ELINT Receiver Capabilities

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Reports and Technical Reports All Technical Reports Collection 2014-09 Commercially Available Low Probability of Intercept Radars and Non-Cooperative ELINT Receiver Capabilities Heinbach, Kathleen Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School, Center for Joint Services Electronic Warfare http://hdl.handle.net/10945/43575 NPS-EC-14-003 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA COMMERCIALLY AVAILABLE LOW PROBABILITY OF INTERCEPT RADARS AND NON-COOPERATIVE ELINT RECEIVER CAPABILITIES by Kathleen Heinbach, Rita Painter, Phillip E. Pace September 2014 Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From-To) 30-09-2014 Technical Report 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER Commercially Available Low Probability of Intercept Radars and Non-Cooperative ELINT Receiver Capabilities 5b. -

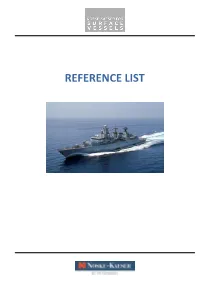

REFERENCE LIST Referencelist Surface Vessels 2017 Rev.05.Xlsx Page 2 of 10

REFERENCE LIST Referencelist Surface vessels 2017 Rev.05.xlsx Page 2 of 10 No. Country Ship type Ship name Ship class Shipyard Year HVAC System HVAC CBRN Protection WaterChilled Plant Provision Cooling Plant Firefighting 1 Frigate El Moudamir MEKO A-200 TKMS 2016/17 X X X X X Algeria 2 Frigate Erradii MEKO A-200 TKMS 2016 X X X X X Tenix Defence System 3 Frigate Perth MEKO 200 2006 X X X X Williamstown Australia Tenix Defence System 4 Frigate Toowoomba MEKO 200 2005 X X X X Williamstown Tenix Defence System 5 Frigate Ballarat MEKO 200 2004 X X X X Williamstown Tenix Defence System 6 Frigate Parramatta MEKO 200 2003 X X X X Williamstown Tenix Defence System 7 Frigate Stuart MEKO 200 2002 X X X X Williamstown Tenix Defence System 8 Frigate Warramunga MEKO 200 2001 X X X X Williamstown Transfield 9 Frigate Arunta MEKO 200 1998 X X X X Williamstown Transfield 10 Frigate Anzac MEKO 200 1996 X X X X Williamstown Daewoo 11 Frigate F25 2000 X X Okpo Bangladesh 12 Peenewerft 13 Patrol forces Gravataí 12 Grajaú Class 2000 X X X Germany Brazil Peenewerft 14 Patrol forces Guaratuba 12 Grajaú Class 1999 X X X Germany Peenewerft 15 Patrol forces Gurupi 12 Grajaú Class 1996 X X X X Germany Peenewerft 16 Patrol forces Guajará 12 Grajaú Class 1995 X X X X Germany Referencelist Surface vessels 2017 Rev.05.xlsx Page 3 of 10 No. Country Ship type Ship name Ship class Shipyard Year HVAC System HVAC CBRN Protection WaterChilled Plant Provision Cooling Plant Firefighting Peenewerft 17 Patrol forces Guaporé 12 Grajaú Class 1995 X X X X Germany Brazil Peenewerft -

PIRACY OFF the COAST of SOMALIA Table of Contents

DIIS REPORT 2017: 10 LEARNING FROM DANISH COUNTER- PIRACY OFF THE COAST OF SOMALIA Table of Contents List of acronyms 4 Abstract 5 Introduction 7 The international response to maritime piracy off the coast 13 of Somalia and drivers of Danish involvement International counter-piracy: a comprehensive but ad hoc approach 15 Drivers of Danish engagement in counter-piracy off the coast of Somalia 18 Combating piracy through law enforcement 25 Danish efforts to combat Somali piracy 27 Lessons learned from Danish participation in combatting piracy 29 Protecting the shipping industry 37 Danish efforts to protect the shipping industry 38 Lessons from Danish engagement with the shipping industry 41 This report is written by Jessica Larsen, PhD, DIIS and Christine Nissen, PhD, DIIS and published by DIIS as part of the Defence and Security Studies. Regional capacity-building 47 Danish participation in the regional capacity-building 48 DIIS · Danish Institute for International Studies of maritime security capabilities Østbanegade 117, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark Lessons from Danish capacity-building in the region around Somalia 50 Tel: +45 32 69 87 87 E-mail: [email protected] Conclusion 57 www.diis.dk Implications: future Danish maritime security engagement 59 Final remarks 64 Layout: Lone Ravnkilde & Viki Rachlitz Printed in Denmark by Eurographic Notes 66 ISBN 978-87-7605-896-8 (print) Literature 68 ISBN 978-87-7605-897-5 (pdf) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge or ordered from www.diis.dk © Copenhagen 2017, the authors and DIIS 3 LIST OF ACRONYMS ABSTRACT AU African Union Since the mid-2000s, piracy off the coast of Somalia has posed a serious threat to BIMCO Baltic and International Maritime Council international shipping and the safety of seafarers. -

![D 32 Daring [Type 45 Batch 1] - 2015 Harpoon](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6950/d-32-daring-type-45-batch-1-2015-harpoon-726950.webp)

D 32 Daring [Type 45 Batch 1] - 2015 Harpoon

D 32 Daring [Type 45 Batch 1] - 2015 Harpoon United Kingdom Type: DDG - Guided Missile Destroyer Max Speed: 28 kt Commissioned: 2015 Length: 152.4 m Beam: 21.2 m Draft: 7.4 m Crew: 190 Displacement: 7450 t Displacement Full: 8000 t Propulsion: 2x Wärtsilä 12V200 Diesels, 2x Rolls-Royce WR-21 Gas Turbines, CODOG Sensors / EW: - Type 1045 Sampson MFR - Radar, Radar, Air Search, 3D Long-Range, Max range: 398.2 km - Type 2091 [MFS 7000] - Hull Sonar, Active/Passive, Hull Sonar, Active/Passive Search & Track, Max range: 29.6 km - Type 1047 - (LPI) Radar, Radar, Surface Search & Navigation, Max range: 88.9 km - UAT-2.0 Sceptre XL - (Upgraded, Type 45) ESM, ELINT, Max range: 926 km - IRAS [CCD] - (Group, IR Alerting System) Visual, LLTV, Target Search, Slaved Tracking and Identification, Max range: 185.2 km - IRAS [IR] - (Group, IR Alerting System) Infrared, Infrared, Target Search, Slaved Tracking and Identification Camera, Max range: 185.2 km - IRAS [Laser Rangefinder] - (Group, IR Alerting System) Laser Rangefinder, Laser Rangefinder, Max range: 0 km - Type 1046 VSR/LRR [S.1850M, BMD Mod] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Radar, Radar, Air Search, 3D Long-Range, Max range: 2000.2 km - Radamec 2500 [EO] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Visual, Visual, Weapon Director & Target Search, Tracking and Identification TV Camera, Max range: 55.6 km - Radamec 2500 [IR] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Infrared, Infrared, Weapon Director & Target Search, Tracking and Identification Camera, Max range: 55.6 km - Radamec 2500 [Laser Rangefinder] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Laser Rangefinder, Laser Rangefinder for Weapon Director, Max range: 7.4 km - Type 1048 - (LPI) Radar, Radar, Surface Search w/ OTH, Max range: 185.2 km Weapons / Loadouts: - Aster 30 PAAMS [GWS.45 Sea Viper] - Guided Weapon.