Select Committee on Crime Prevention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tabled Papers-0471St

FIRST SESSION OF THE FORTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT Register of Tabled Papers – First Session – Forty–Seventh Parliament 1 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF QUEENSLAND REGISTER OF TABLED PAPERS FIRST SESSION OF THE FORTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT TUESDAY, 3 NOVEMBER 1992 1 P ROCLAMATION CONVENING PARLIAMENT: The House met at ten o'clock a.m. pursuant to the Proclamation of Her Excellency the Governor bearing the date the Fifteenth day of October 1992 2 COMMISSION TO OPEN PARLIAMENT: Her Excellency the Governor, not being able conveniently to be present in person this day, has been pleased to cause a Commission to be issued under the Public Seal of the State, appointing Commissioners in Order to the Opening and Holding of this Session of Parliament 3 M EMBERS SWORN: The Premier (Mr W.K. Goss) produced a Commission under the Public Seal of the State, empowering him and two other Members of the House therein named, or any one or more of them, to administer to all or any Members or Member of 4 the House the oath or affirmation of allegiance to Her Majesty the Queen required by law to be taken or made and subscribed by every such Member before he shall be permitted to sit or vote in the said Legislative Assembly 5 The Clerk informed the House that the Writs for the various Electoral Districts had been returned to him severally endorsed WEDNESDAY, 4 NOVEMBER 1992 6 O PENING SPEECH OF HER EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR: At 2.15 p.m., Her Excellency the Governor read the following speech THURSDAY, 5 NOVEMBER 1992 27 AUTHORITY TO ADMINISTER OATH OR AFFIRMATION OF ALLEGIANCES TO M EMBERS: Mr Speaker informed the House that Her Excellency the Governor had been pleased to issue a Commission under the Public Seal of the State empowering him to administer the oath or affirmation of allegiance to such Members as might hereafter present themselves to be sworn P ETITIONS: The following petitions, lodged with the Clerk by the Members indicated, were received - 28 Mr Veivers from 158 petitioners praying for an increase in the number of police on the Gold Coast. -

Gov Gaz Week 6 Colour.Indd

777 15 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 41 Friday, 23 February 2001 Published under authority by the Government Printing Service LEGISLATION Proclamations Community Relations Commission and Principles of Multiculturalism Act 2000 No 77—Proclamation GORDON SAMUELS, , GovernorGovernor I, the Honourable Gordon Samuels AC, CVO, Governor of the State of New South Wales, with the advice of the Executive Council, and in pursuance of section 2 of the Community Relations Commission and Principles of Multiculturalism Act 2000, do, by this my Proclamation, appoint 13 March 2001 as the day on which that Act commences. Signed andat sealed sealed Sydney, at Sydney, this this 21st day day of of February 2001. 2001. By His Excellency’s Command, L.S. BOB CARR, M.P., Premier,Premier, Minister Minister for for the the Arts Arts and and Minister Minister for for CitizenshipCitizenship GOD SAVE THE QUEEN! p01-012-p01.846 Page 1 778 LEGISLATION 23 February 2001 Crimes Legislation Further Amendment Act 2000 No 107—Proclamation GORDON SAMUELS, , GovernorGovernor I, the Honourable Gordon Samuels AC, CVO, Governor of the State of New South Wales, with the advice of the Executive Council, and in pursuance of section 2 of the Crimes Legislation Further Amendment Act 2000, do, by this my Proclamation, appoint 23 February 2001 as the day on which the uncommenced provisions of that Act commence. Signed andand sealedsealed at at Sydney, Sydney, this this 21st day day of February of February 2001. 2001. By His Excellency’s Command, L.S. BOB DEBUS, M.P., AttorneyAttorney General GOD SAVE THE QUEEN! Explanatory note The object of this proclamation is to commence the provisions of the Crimes Legislation Further Amendment Act 2000 that relate to the offence of possession of substances called precursors. -

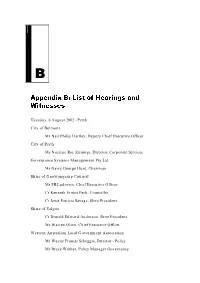

Appendix B: List of Hearings and Witnesses

B Appendix B: List of Hearings and Witnesses Tuesday, 6 August 2002 - Perth City of Belmont Mr Neil Philip Hartley, Deputy Chief Executive Officer City of Perth Ms Noelene Rae Jennings, Director, Corporate Services Governance Systems Management Pty Ltd Mr Garry George Hunt, Chairman Shire of Gnowangerup Council Mr FB Ludovico, Chief Executive Officer Cr Kenneth Ernest Pech, Councillor Cr Janet Patricia Savage, Shire President Shire of Yalgoo Cr Donald Edward Anderson, Shire President Mr Warren Olsen, Chief Executive Officer Western Australian Local Government Association Mr Wayne Francis Scheggia, Director - Policy Mr Bruce Wittber, Policy Manager Governance 166 RATES AND TAXES: A FAIR SHARE FOR RESPONSIBLE LOCAL GOVERNMENT Wednesday, 4 September 2002 - Canberra Country Public Libraries Association of New South Wales Mr Peter Conlon, Former Secretary Cr Susan Whelan, Deputy Chairperson Crookwell Shire Council Mr Brian Wilkinson, General Manager Department of Transport and Regional Services Ms Julia Evans, Acting Director, Review of Non-Road Transport Industry Programs Mr Andrew Hrast, Director, Roads to Recovery Program Mr Mike Mrdak, First Assistant Secretary, Territories and Local Government Division Ms Diane Podlich, Assistant Director, Economic Policy, Territories and Local Government Division Mr Geof Watts, Director, Economic Policy, Territories and Local Government National Farmers Federation Miss Denita Harris, Policy Manager & Industrial Relations Advocate Mr Michael Potter, Policy Manager, Economics The Commonwealth Grants Commission -

The Poultry Industry Regulations of 1946 Queensland Reprint

Warning “Queensland Statute Reprints” QUT Digital Collections This copy is not an authorised reprint within the meaning of the Reprints Act 1992 (Qld). This digitized copy of a Queensland legislation pamphlet reprint is made available for non-commercial educational and research purposes only. It may not be reproduced for commercial gain. ©State of Queensland "THE POULTRY INDUSTRY REGULATIONS OF 1946" Inserted by regulations published Gazette 3 March 1947, p. 761; and amended by regulations published Gazette 13 November 1968, p. 2686; 23 July, 1949, p. 224; 25 March 1950, p. 1166; 20 January 1951, p. 162; 9 June 1951, p. 686; 8 November 1952, p. 1136; 16 May 1953, p. 413; 2 July 1955, p. 1118; 3 March 1956, p. 633; 5 April 1958, p. 1543; 14 June 1958, p. 1488, 13 December 1958, p. 1923; 25 April 1959, p. 2357; 10 October 1959, p. 896; 12 December 1959, p. 2180; 12 March 1960, pp. 1327-30; 2 April 1960, p. 1601; 22 April1961, p. 22.53; 11 August 1962, p. 1785; 23 November 1963, p. 1011; 22 February 1964, p. 710; 7 March 1964, p. 865; 16 January 1965, p. 117; 3 July 1965, p. 1323; 12 February 1966, p. 1175; 26 February 1966, p. 1365; 16 April 1966, p. 1983; 7 May 1966, pp. 160-1; 9 July 1966, p. 1352; 27 August 1966, p. 2022. Department of Agriculture and Stock, Brisbane, 27th February, 1947. HIS Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, has, in pursuance of the provisions of "The Poultry Industry Act of 1946," been pleased to make the following Regulations:- 1. -

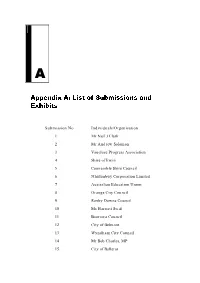

Appendix A: List of Submissions and Exhibits

A Appendix A: List of Submissions and Exhibits Submission No Individuals/Organisation 1 Mr Neil J Clark 2 Mr Andrew Solomon 3 Vaucluse Progress Association 4 Shire of Irwin 5 Coonamble Shire Council 6 Nhulunbuy Corporation Limited 7 Australian Education Union 8 Orange City Council 9 Roxby Downs Council 10 Ms Harriett Swift 11 Boorowa Council 12 City of Belmont 13 Wyndham City Council 14 Mr Bob Charles, MP 15 City of Ballarat 148 RATES AND TAXES: A FAIR SHARE FOR RESPONSIBLE LOCAL GOVERNMENT 16 Hurstville City Council 17 District Council of Ceduna 18 Mr Ian Bowie 19 Crookwell Shire Council 20 Crookwell Shire Council (Supplementary) 21 Councillor Peter Dowling, Redland Shire Council 22 Mr John Black 23 Mr Ray Hunt 24 Mosman Municipal Council 25 Councillor Murray Elliott, Redland Shire Council 26 Riddoch Ward Community Consultative Committee 27 Guyra Shire Council 28 Gundagai Shire Council 29 Ms Judith Melville 30 Narrandera Shire Council 31 Horsham Rural City Council 32 Mr E. S. Cossart 33 Shire of Gnowangerup 34 Armidale Dumaresq Council 35 Country Public Libraries Association of New South Wales 36 City of Glen Eira 37 District Council of Ceduna (Supplementary) 38 Mr Geoffrey Burke 39 Corowa Shire Council 40 Hay Shire Council 41 District Council of Tumby Bay APPENDIX A: LIST OF SUBMISSIONS AND EXHIBITS 149 42 Dalby Town Council 43 District Council of Karoonda East Murray 44 Moonee Valley City Council 45 City of Cockburn 46 Northern Rivers Regional Organisations of Councils 47 Brisbane City Council 48 City of Perth 49 Shire of Chapman Valley 50 Tiwi Islands Local Government 51 Murray Shire Council 52 The Nicol Group 53 Greater Shepparton City Council 54 Manningham City Council 55 Pittwater Council 56 The Tweed Group 57 Nambucca Shire Council 58 Shire of Gingin 59 Shire of Laverton Council 60 Berrigan Shire Council 61 Bathurst City Council 62 Richmond-Tweed Regional Library 63 Surf Coast Shire Council 64 Shire of Campaspe 65 Scarborough & Districts Progress Association Inc. -

Motioner 2001:1 T 9

G 0 o KOMMUNFULLMÄKTIGE Motioner 2001:1 T 9 2001:1 Motion av Rebwar Hassan och Christopher Öd- mann (båda mp) om krav på testat kött i skolor och på andra kommunala inrättningar m.m. När miljöpartister under årens lopp har föreslagit att endast KRAV-märkta eller motsvarande råvaror ska serveras i skolor och på andra kommunala in- rättningar, har avslagen från ansvariga politiker motiverats med att detta är inget kommunen ska lägga sig i och att statliga myndigheter i övrigt svarar för kvalitetskontrollen. I dag vet alla bättre och rädslan för nervsjukdomen BSE märks numera även på lrekrogar, där man helst använder ursprungsbetecknat kött. BSE sprids genom den bisarra idéen att utfordra vegetarianer, som kor och får är, med köttmjöl från kadaver (sjuka och självdöda djur som malts ner). I Sverige har hittills den ansvariga jordbruksministern inte velat inse allvaret i frågan vilket gör det ännu angelägnare att på kommunal nivå skydda så många invå- nare som möjligt. Oskarshamns kommun har visat vägen genom att sluta servera även svenskt kött. Låt oss i Stockholm reagera lika snabbt och kraftfullt. I detta fall om nå- got bör försiktighetsprincipen råda. Samtidigt bör Stockholms stad hos regeringen hemställa att testning av kött genomförs i hela landet. Den uppkomna debatten bör föras i ett vidare perspektiv. Frågor om djur- hållning, livsmedel, etik och hälsa bör diskuteras bl a i stadens skolor. Med- vetna konsumenter kan göra egna val kring den mat de önskar äta och välja bort produkter de anser oetiska eller ohälsosamma. Med hänvisning till ovanstående föreslår vi att kommunfullmäktige beslu- tar att Stockholms stad endast ska servera garanterat smittfritt kött, d.v.s. -

MAJOR and SPECIAL EVENTS PLANNING a Guide for Promoters

PRACTICE NOTE MAJOR AND SPECIAL EVENTS PLANNING A Guide for Promoters and Councils NSW DEPARTMENT OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN CO-OPERATION WITH NSW POLICE SERVICE NSW ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION AUTHORITY NSW DEPARTMENT OF URBAN AFFAIRS AND PLANNING CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE 4 IMPACTS OF MAJOR AND SPECIAL EVENTS 5 What is Economic Impact Assessment? 6 What is Social Impact Assessment? 7 Why do a Social Impact Assessment for a major or special event? 8 REFERENCES 10 APPENDICES 12 APPENDIX A 13 APPENDIX B 15 2 INTRODUCTION This practice note or guide has been prepared to provide councils, event promoters and the general public with information about how to successfully facilitate major and special events for their communities. These events include street parades, motor races, cycling races, jazz festivals, cultural celebrations, sporting events, open air theatres and concerts, and balls or dance parties and can often attract large numbers of people. A lot of time and effort goes into planning and promoting these events and they are often seen as a way of creating employment and providing economic benefits for the local community. Councils play a variety of roles, from event manager to consent authority, and have to weigh up the advantages and disadvantages for everyone in their community before they give approval for the event to go ahead. Events are often complex and may depend on approvals from a range of different agencies. The key to staging a successful event is good communication, as early as possible in the process, between the promoter of the event and the local council and other consent authorities such as the Police and the Environment Protection Authority. -

Valuing Ecosystem Goods and Services

Ecological Economics 50 (2004) 163–194 www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolecon METHODS Valuing ecosystem goods and services: a new approach using a surrogate market and the combination of a multiple criteria analysis and a Delphi panel to assign weights to the attributes Ian A. Curtis* School of Environmental Studies and Geography, Faculty of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, P.O. Box 6811 Cairns, Queensland 4870, Australia Received 22 February 2003; received in revised form 5 February 2004; accepted 20 February 2004 Available online 25 September 2004 Abstract A new approach to valuing ecosystem goods and services (EGS) is described which incorporates components of the economic theory of value, the theory of valuation (US f appraisal), a multi-model multiple criteria analysis (MCA) of ecosystem attributes, and a Delphi panel of experts to assign weights to the attributes. The total value of ecosystem goods and services in the various tenure categories in the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area (WTWHA) in Australia was found to be in the range AUD$188 to $211 million yearÀ 1, or AUD$210 to 236 haÀ 1 yearÀ 1 across tenures, as at 30 June 2002. Application of the weightings assigned by the Delphi panelists and assessment of the ecological integrity of the various tenure categories resulted in values being derived for individual ecosystem services in the World Heritage Area. Biodiversity and refugia were the two attributes ranked most highly at AUD$18.6 to $20.9 million yearÀ 1 and AUD$16.6 to $18.2 million yearÀ 1, respectively. D 2004 Elsevier B.V. -

Queensland Government Gazette

[591] Queensland Government Gazette PP 451207100087 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. CCCXXXVII] (337) FRIDAY, 22 OCTOBER, 2004 [No. 39 Integrated Planning Act 1997 TRANSITIONAL PLANNING SCHEME NOTICE (NO. 2) 2004 In accordance with section 6.1.11(2) of the Integrated Planning Act 1997, I hereby nominate the date specified in the following schedule as the revised day on which the transitional planning scheme, for the local government area listed in the schedule, will lapse: SCHEDULE Townsville City 31/12/04 Desley Boyle MP Minister for Environment, Local Government, Planning and Women 288735—1 592 QUEENSLAND GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, No. 39 [22 October, 2004 Adopted Amendment to the Planning Scheme: Coastal Major Road Network Infrastructure Charges Plan Section 6.1.6 of the Integrated Planning Act 1997 The provisions of the Integrated Planning and Other Legislation Act 2003 (IPOLAA 2003) commenced on 4 October 2004, and in accordance with the conditions of approval for the Coastal Major Road Network Infrastructure Charges Plan (CMRNICP) issued by the Minister for Local Government and Planning dated 18 May 2004 and 3 June 2004, Council: - Previously adopted on 10 June 2004, an amendment to the planning scheme for the Shire of Noosa by incorporating the infrastructure charges plan, the Coastal Major Road Network Infrastructure Charges Plan (CMRNICP) applying to “exempt and self-assessable” development; and - On 14 October 2004, adopted an amendment to the planning scheme for the Shire of Noosa by incorporating “the balance of” the Coastal -

November 1934, Volume 6, No. 1

From the Divisions. MetroDohtan.~. macadam over a length of 3 miles, commencing about mile from the I'rkc's Hifihway at Unanderra and Contractor L. 1. Manstield is constructing a 5-span extending towards Port Kembla. Difficulty was pre- rcinforcetl concrete In-itlge. 202 ft. long, on the Great viously expcrienced in maintaining the road in satis- Western Highway at St. Marys. The new bridge will factory order. owing to leaks from an old water main be on a greatly imp-ovetl aligiiinent and will be raised under the pavement, and hcforc proceeding with the above the level of foods which have periodically inter- reconstruction of the road, arrangements were made rupted traffic at this point in the past. On the Great Western 1Iighway. improvements to grade and alignment are being carried out hctween Yetholme and Bathurst in Turon Shire. Widening and realignment are in progress between Faulconbridge and Woodford on the Great Western Higliway in Blue Mountains Shire. Good progress is being made by the contractors, Messrs. Joncs Uroa., with the construction of two re- inforced concrete bridges over Rocks Creek al X m. ancl 11 ni. from Bathurst on the North-\\'estern Highway ill I\bercrombie Shire. 'The former will replace an old timber bridge, and the new structure at I I tn. will be located to improve the alignment and replace an old tinibcr structurc on masonry ahutments. The McLean Construction Co. is carrying out the A stone arched culvert. built in 1819 and still in good widening of Lennox bridge in Church-street (State condition. at Tamarang Creek. -

Government Gazette

7325 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 142 Friday, 3 September 2004 Published under authority by Government Advertising and Information LEGISLATION Allocation of Administration of Acts The Cabinet Offi ce, Sydney 1 September 2004 ALLOCATION OF THE ADMINISTRATION OF ACTS HER Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, has approved of the administration of the Acts listed in the attached Schedule being vested in the Ministers indicated against each respectively, subject to the administration of any such Act, to the extent that it directly amends another Act, being vested in the Minister administering the other Act or the relevant portion of it. The arrangements are in substitution for those in operation before the date of this notice. BOB CARR, Premier SCHEDULE PREMIER Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 No. 48, Part 9A (remainder, Attorney General) Anzac Memorial (Building) Act 1923 No. 27 Australia Acts (Request) Act 1985 No. 109 Competition Policy Reform (New South Wales) Act 1995 No. 8 Constitution Act 1902 No. 32 Constitution Further Amendment (Referendum) Act 1930 No. 2 Constitution (Legislative Council Reconstitution) Savings Act 1993 No. 19 Election Funding Act 1981 No. 78 Essential Services Act 1988 No. 41, Parts 1 and 2 (remainder, Minister for Industrial Relations) Freedom of Information Act 1989 No. 5 Independent Commission Against Corruption Act 1988 No. 35 Independent Commission Against Corruption (Commissioner) Act 1994 No. 61 Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal Act 1992 No. 39 Interpretation Act 1987 No. 15 Legislation Review Act 1987 No. 165 Licensing and Registration (Uniform Procedures) Act 2002 No. 28 Mutual Recognition (New South Wales) Act 1992 No. -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 50 Friday, 6 March 2009 Published Under Authority by Government Advertising

1301 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 50 Friday, 6 March 2009 Published under authority by Government Advertising LEGISLATION Announcement Online notification of the making of statutory instruments Following the commencement of the remaining provisions of the Interpretation Amendment Act 2006, the following statutory instruments are to be notified on the official NSW legislation website (www.legislation.nsw.gov.au) instead of being published in the Gazette: (a) all environmental planning instruments, on and from 26 January 2009, (b) all statutory instruments drafted by the Parliamentary Counsel’s Office and made by the Governor (mainly regulations and commencement proclamations) and court rules, on and from 2 March 2009. Instruments for notification on the website are to be sent via email to [email protected] or fax (02) 9232 4796 to the Parliamentary Counsel's Office. These instruments will be listed on the “Notification” page of the NSW legislation website and will be published as part of the permanent “As Made” collection on the website and also delivered to subscribers to the weekly email service. Principal statutory instruments also appear in the “In Force” collection where they are maintained in an up-to-date consolidated form. Notified instruments will also be listed in the Gazette for the week following notification. For further information about the new notification process contact the Parliamentary Counsel’s Office on (02) 9321 3333. 1302 LEGISLATION 6 March 2009 Online notification of the