Representing British Working Class at the Turn of the New Millennium: a Study of the Royle Family

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kelsale-Cum-Carlton Parish Council 31 Kings Road, Leiston, Suffolk, IP16 4DA Tel: 07733 355657, E-Mail: [email protected]

Kelsale-cum-Carlton Parish Council 31 Kings Road, Leiston, Suffolk, IP16 4DA Tel: 07733 355657, E-mail: [email protected] www.kelsalecarltonpc.org.uk MINUTES OF THE ANNUAL PARISH MEETING HELD ON WEDNESDAY 17th April 2019 IN KELSALE VILLAGE HALL AT 7:00PM __________________________________________________________________________ Present: Cllr Alan Revell (Chairman) & Elizabeth Flight – Parish Clerk. Cllr Alan Revell (Chairman) welcomed members of the public and representatives and formally opened the meeting. Public Forum 1. To receive Apologies for Absence. Apologies were accepted from – Cllr Burslem (away), Cllr Martin Lumb, Jenni Aird, Auriol and Michael Marson 2. Approval of the draft minutes of the Annual Parish Meeting held on 18th April 2018. The Chairman made a note that last year’s minutes had been available recently on the website and village noticeboards to read before approval. The minutes were taken as read and proposed by Cllr Galloway for approval by seconded by Cllr Buttle. A vote was taken where they were agreed, and they were duly signed by the Chairman as a true record of the meeting. 3. Matters Arising from the Annual Parish Meeting held on 18th April 2018. There were none. The Chairman thanked Cllr Roberts for organising tonight’s presentation. Cllr Roberts announced that a film called Town Settlement would be shown. Cllr Roberts who had source the film gave a brief introduction and explanation of the film before it was shown. Cllr Roberts also announced that there is a competition – if anyone can recognise 10 things in the film to let them know after the meeting. INTERVAL (15 Minutes) – Very enjoyable light refreshments were served – thank you to all those who assisted in organising these. -

The Meaning of Katrina Amy Jenkins on This Life Now Judi Dench

Poor Prince Charles, he’s such a 12.09.05 Section:GDN TW PaGe:1 Edition Date:050912 Edition:01 Zone: Sent at 11/9/2005 17:09 troubled man. This time it’s the Back page modern world. It’s all so frenetic. Sam Wollaston on TV. Page 32 John Crace’s digested read Quick Crossword no 11,030 Title Stories We Could Tell triumphal night of Terry’s life, but 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Author Tony Parsons instead he was being humiliated as Dag and Misty made up to each other. 8 Publisher HarperCollins “I’m going off to the hotel with 9 10 Price £17.99 Dag,” squeaked Misty. “How can you do this to me?” Terry It was 1977 and Terry squealed. couldn’t stop pinching “I am a woman in my own right,” 11 12 himself. His dad used to she squeaked again. do seven jobs at once to Ray tramped through the London keep the family out of night in a daze of existential 13 14 15 council housing, and here navel-gazing. What did it mean that he was working on The Elvis had died that night? What was 16 17 Paper. He knew he had only been wrong with peace and love? He wound brought in because he was part of the up at The Speakeasy where he met 18 19 20 21 new music scene, but he didn’t care; the wife of a well-known band’s tour his piece on Dag Wood, who uncannily manager. “Come back to my place,” resembled Iggy Pop, was on the cover she said, “and I’ll help you find John 22 23 and Misty was by his side. -

The British Academy Television Awards Sponsored by Pioneer

The British Academy Television Awards sponsored by Pioneer NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED 11 APRIL 2007 ACTOR Programme Channel Jim Broadbent Longford Channel 4 Andy Serkis Longford Channel 4 Michael Sheen Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! BBC4 John Simm Life On Mars BBC1 ACTRESS Programme Channel Anne-Marie Duff The Virgin Queen BBC1 Samantha Morton Longford Channel 4 Ruth Wilson Jane Eyre BBC1 Victoria Wood Housewife 49 ITV1 ENTERTAINMENT PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Ant & Dec Saturday Night Takeaway ITV1 Stephen Fry QI BBC2 Paul Merton Have I Got News For You BBC1 Jonathan Ross Friday Night With Jonathan Ross BBC1 COMEDY PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Dawn French The Vicar of Dibley BBC1 Ricky Gervais Extra’s BBC2 Stephen Merchant Extra’s BBC2 Liz Smith The Royle Family: Queen of Sheba BBC1 SINGLE DRAMA Housewife 49 Victoria Wood, Piers Wenger, Gavin Millar, David Threlfall ITV1/ITV Productions/10.12.06 Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! Andy de Emmony, Ben Evans, Martyn Hesford BBC4/BBC Drama/13.03.06 Longford Peter Morgan, Tom Hooper, Helen Flint, Andy Harries C4/A Granada Production for C4 in assoc. with HBO/26.10.06 Road To Guantanamo Michael Winterbottom, Mat Whitecross C4/Revolution Films/09.03.06 DRAMA SERIES Life on Mars Production Team BBC1/Kudos Film & Television/09.01.06 Shameless Production Team C4/Company Pictures/01.01.06 Sugar Rush Production Team C4/Shine Productions/06.07.06 The Street Jimmy McGovern, Sita Williams, David Blair, Ken Horn BBC1/Granada Television Ltd/13.04.06 DRAMA SERIAL Low Winter Sun Greg Brenman, Adrian Shergold, -

Encounters with the Neighbour in 1970S' British Multicultural Comedy

Postcolonial Interventions, Vol. IV, Issue 1 Encounters with the Neighbour in 1970s’ British Multicultural Comedy Sarah Ilott “If you don’t shut up, I’ll come and move in next door to you!” Such was the frequent response to audience heckles made by Britain’s first well-known black come- dian, Charlie Williams (Leigh 2006). Williams’s response appropriated racist rhetoric of the time, in which the black neighbour was frequently mobilised as an object of fear, threatening the imagined homogeneity of for- merly white communities. Having frequently been on the receiving end of racist taunts such as “Get back to Af- rica” as a professional footballer for Doncaster Rovers in the 1940s and ’50s, Williams was able to claim some 14 Postcolonial Interventions, Vol. IV, Issue 1 of the power of the Teller of the joke through such put-downs, rather than solely occupying the position of the Butt of racist jokes and slurs. However, the fact was that Williams was forced to rely on self-deprecation and the reiteration of racial stereotype gestures to his need to find favour with the predominantly white audiences of the northern working men’s clubs that he toured and the mainstream audiences of ITV’s prime time hit, The Comedians (ITV, 1971-93), on which he was showcased alongside notable racists such as Bernard Manning. De- spite lamenting the “very stupid and very immature” tone of Williams’s self-mocking jokes, comedian Lenny Henry – who lived with the unfortunate legacy of what was expected of black comedians, particularly in the North – acknowledged that Williams did “what you’ve got to do if it’s a predominantly white audience – you’ve got to put yourself, and other people, down” (qtd. -

SMA 1991.Pdf

C 614 5. ,(-7-1.4" SOUTH MIDLANDS ARCHAEOLOGY The Newsletter of the Council for British Archaeology, South Midlands Group (Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire) NUMBER 21, 1991 CONTENTS Page Spring Conference 1991 1 Bedfordshire Buckinghamshire 39 Northamptonshire 58 Ox-fordshire 79 Index 124 EDITOR: Andrew Pike CHAIRMAN: Dr Richard Ivens Bucks County Museum Milton Keynes Archaeology Unit Technical Centre, Tring Road, 16 Erica Road Halton, Aylesbury, HP22 5PJ Stacey Bushes Milton Keynes MX12 6PA HON SEC: Stephen Coleman TREASURER: Barry Home County Planning Dept, 'Beaumont', Bedfordshire County Council Church End, County Hall, Edlesborough, Bedford. Dunstable, Beds. MX42 9AP LU6 2EP Typeset by Barry Home Printed by Central Printing Section, Bucks County Council ISSN 0960-7552 CBA South Midlands The two major events of CBA IX's year were the AGM and Spring Conference, both of which were very successful. CHAIRMAN'S LETTER Last year's A.G.M. hosted the Beatrice de Cardi lecture and the speaker, Derek Riley, gave a lucid account of his Turning back through past issues of our journal I find a pioneering work in the field of aerial archaeology. CBA's recurrent editorial theme is the parlous financial state of President, Professor Rosemary Cramp, and Director, Henry CBA IX and the likelihood that SMA would have to cease Cleere also attended. As many of you will know Henry publication. Previous corrunittees battled on and continued Cleere retires this year so I would like to take this to produce this valuable series. It is therefore gratifying to opportunity of wishing him well for the future and to thank note that SMA has been singled out as a model example in him for his many years of service. -

Don Warrington W1D 6LD

www.cam.co.uk Email [email protected] Address Don 55-59 Shaftesbury Avenue London Warrington W1D 6LD Telephone +44 (0) 20 7292 0600 Television Title Role Director Production THE WORLD ACCORDING TO GRANDPA Grandpa Alexander James Jacob Milkshake! DEATH IN PARADISE- All series produced Selwyn Patterson Various BBC THE FIVE Ray Kenwood Mark Tonderai Sky THE ARK Paul Red Productions BBC CHASING SHADOWS CS Drayton Jim O'Hanlon ITV LAW AND ORDER Callaghan Andy Goddard ITV LEWIS Prof Woolf David O'Neill ITV THIS IS JINSY Chief Thinker Matt Lipsey BBC WAKING THE DEAD Adam Barclay Tim Fywell BBC GOING POSTAL Priest Jon Jones SKY CASUALTY Trevor- Semi Regular Various BBC LAW & ORDER Chief Commissioner Andy Goddard ITV COMET Futureshock Keith Boak Channel 5/ Darlow Smithson NEW STREET LAW Judge Ken Winyard Various BBC/Red Productions DIAMOND GEEZER Hector Paul Harrision YTV ALL STAR COMEDY SHOW - David Evans ITV THE CROUCHES Bailey Nick Wood BBC TO PLAY THE KING Graham Gaunt Paul Seed BBC ARABIAN KNIGHTS Hari Ben Karim Steve Barron Hallmark Productions CATS EYES Nigel Beaumont Various TVS MAN CHILD Patrick Various BBC THE ARMAND IANNUCCI Ivy Diner Channel 4 Talkback TRAIL & TRIBUTION Willard Pembroke Various ITV RISING DAMP Philip Smith Various ITV Theatre Title Role Director Production DEATH OF A SALESMAN Willy Loman Sarah Frankcom Royal Exchange GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS George Aaronow Sam Yates Playhouse Theatre KING LEAR King Lear Michael Buffong Talawa Theatre Company ALL MY SONS Joe Keller Michael Buffong Manchester Royal Exchange DRIVING MISS -

Disabling Comedy: “Only When We Laugh!”

Disabling Comedy: “Only When We Laugh!” Dr. Laurence Clark, North West Disability Arts Forum (Paper presented at the ‘Finding the Spotlight’ Conference, Liverpool Institute for the Performing Arts, 30th May 2003) Abstract Traditionally comedy involving disabled people has extracted humour from people’s impairments – i.e. a “functional limitation”. Examples range from Shakespeare’s ‘fool’ character and Elizabethan joke books to characters in modern TV sitcoms. Common arguments for the use of such disempowering portrayals are that “nothing is meant by them” and that “people should be able to laugh at themselves”. This paper looks at the effects of such ‘disabling comedy’. These include the damage done to the general public’s perceptions of disabled people, the contribution to the erosion of a disabled people’s ‘identity’ and how accepting disablist comedy as the ‘norm’ has served to exclude disabled writers / comedians / performers from the profession. 1. Introduction Society has been deriving humour from disabled people for centuries. Elizabethan joke books were full of jokes about disabled people with a variety of impairments. During the 17th and 18th centuries, keeping 'idiots' as objects of humour was common among those who had the money to do so, and visits to Bedlam and other 'mental' institutions were a typical form of entertainment (Barnes, 1992, page 14). Bilken and Bogdana (1977) identified “the disabled person as an object of ridicule” as one of the ten media stereotypes of disabled people. Apart from ridicule, disabled people have been largely excluded from the world of comedy in the past. For example, in the eighties American stand-up comedian George Carlin was arrested whilst doing his act for swearing in front of young disabled people. -

1 © 2013 Yougov Ltd. All Rights Reserved Yougov.Co.Uk Liberal

Liberal Democrat rank Have I Got News for You 1 Mock the Week 2 QI 3 Black Books 4 The IT Crowd 5 Brass Eye 6 Doctor Who 7 Red Dwarf 8 Futurama 9 Newswipe with Charlie Brooker 10 Family Guy 11 Russell Howard's Good News 12 Pride and Prejudice 13 Sherlock 14 The Thick of It 15 Being Human 16 Wallace and Gromit 17 Grand Designs 18 Elementary 19 Bremner, Bird and Fortune 20 8 Out of 10 Cats 21 Just a Minute 22 Blackadder 23 The Big Bang Theory 24 Fry's Planet Word 25 Jeeves and Wooster 26 Spaced 27 Dexter 28 Castle 29 The Armando Iannucci Shows 30 House of Cards 31 Green Wing 32 Firefly 33 That Mitchell And Webb Look 34 Buffy the Vampire Slayer 35 Parks and Recreation 36 Brainiac 37 Whose Line Is It Anyway? 38 Time Team 39 Tomorrow's World 40 Scrubs 41 Peep Show 42 Knowing Me, Knowing You... with Alan Partridge 43 BBC News 44 Campus 45 The Golden Age of Canals 46 That Was The Week That Was 47 Charlie Brooker's Screenwipe 48 1 © 2013 YouGov Ltd. All Rights Reserved yougov.co.uk Liberal Democrat rank Look Around You 49 Stand Up for the Week 50 Arrested Development 51 Dirk Gently 52 Stingray 53 The Sunday Night Project 54 Would I Lie To You? 55 Psychoville 56 The Big Fat Quiz of the Year 57 Wonders of the Universe 58 South Park 59 Vicious 60 Watson & Oliver 61 Dead Ringers 62 Absolutely Fabulous 63 Extreme Makeover 64 True Blood 65 Jack Dee Live at the Apollo 66 Nigella Bites 67 Planet Earth 68 Hancock's Half Hour 69 Friends 70 Putin, Russia and the West 71 How the Earth Was Made 72 Kath & Kim 73 Changing Rooms 74 My So-Called Life 75 Click 76 Ask Rhod Gilbert 77 Vic Reeves Big Night Out 78 Batman 79 How Clean is Your House? 80 Goodness Gracious Me 81 Supernatural 82 Walking with Dinosaurs 83 American Dad! 84 The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy 85 The Day Today 86 Not the Nine O'Clock News 87 Argumental 88 Is It Bill Bailey? 89 Russell Howard Live 90 Acorn Antiques 91 The Impressions Show with Culshaw and Stephenson 92 My Hero 93 The Office 94 House 95 New Girl 96 The Returned 97 Big Train 98 Due South 99 Destination Titan 100 2 © 2013 YouGov Ltd. -

BBC ONE AUTUMN 2006 Designed by Jamie Currey Bbc One Autumn 2006.Qxd 17/7/06 13:05 Page 3

bbc_one_autumn_2006.qxd 17/7/06 13:03 Page 1 BBC ONE AUTUMN 2006 Designed by Jamie Currey bbc_one_autumn_2006.qxd 17/7/06 13:05 Page 3 BBC ONE CONTENTS AUTUMN P.01 DRAMA P. 19 FACTUAL 2006 P.31 COMEDY P.45 ENTERTAINMENT bbc_one_autumn_2006.qxd 17/7/06 13:06 Page 5 DRAMA AUTUMN 2006 1 2 bbc_one_autumn_2006.qxd 17/7/06 13:06 Page 7 JANE EYRE Ruth Wilson, as Jane Eyre, and Toby Stephens, as Edward Rochester, lead a stellar cast in a compelling new adaptation of Charlotte Brontë’s much-loved novel Jane Eyre. Orphaned at a young age, Jane is placed in the care of her wealthy aunt Mrs Reed, who neglects her in favour of her own three spoiled children. Jane is branded a liar, and Mrs Reed sends her to the grim and joyless Lowood School where she stays until she is 19. Determined to make the best of her life, Jane takes a position as a governess at Thornfield Hall, the home of the alluring and unpredictable Edward Rochester. It is here that Jane’s journey into the world, and as a woman, begins. Writer Sandy Welch (North And South, Magnificent Seven), producer Diederick Santer (Shakespeare Retold – Much Ado About Nothing) and director Susanna White (Bleak House) join forces to bring this ever-popular tale of passion, colour, madness and gothic horror to BBC One. Producer Diederick Santer says: “Sandy’s brand-new adaptation brings to life Jane’s inner world with beauty, humour and, at times, great sadness. We hope that her original take on the story will be enjoyed as much by long- term fans of the book as by those who have never read it.” The serial also stars Francesca Annis as Lady Ingram, Christina Cole as Blanche Ingram, Lorraine Ashbourne as Mrs Fairfax, Pam Ferris as Grace Poole and Tara Fitzgerald as Mrs Reed. -

Off Campus Students Question Safety October Is Alcohol Awareness Month

•-" --NEWS- -SPORTS^ Sorfiestudents^questioh • The Red Foxes were. whether the food quality blanked for the second has gone up in the hew- game in a! row on Satur lcx>kMaristdininghall, day, falling 31-0 to Pg-3 Duquesne, pg. 16 THE CIRCLE the student newspaper of N|arist College VOLUME #53 ISSUE #2 HTTP://WWW.ACADEMIC.MARIST.EDV/C1RCLE SEPTEMBER 23, 1999 Off campus students question safety byJAIMETOMEO thorities must be published for who were mugged walking back Asst. News Editor the past three calendar years. to Marist at night: It is enough Mother always said to go ev During the 1998 school year to make students ask the ques erywhere with a buddy and look there were three reported bur tion, "Am 1 really safe off-cam both ways before crossing the glaries reported and one weap pus?" street to be safe. ons possession. This is a de It is a question all students Under the federal law entitled cline from the two proceeding should take into consideration "Student Right to Know and school years. • before walking past the new Campus Security Act", statis Yet students still hear repeated black metal fence. Unfortunately tics regarding certain crimes re stories of the student who was for many, becoming a statistic of ported to campus security au dragged by a cab and of people ...please see CRIME, pg. 4 Circle photo/Megan Williams Multiple crimes have occured near the Palace Diner recently. Parents to take jawexthe cahipus . arpund;-carnpus,~and .various r byKATEREILLY sporting events, there is also the '"; ' Staff Writer opportunity for parents and The sight of students clean students to take a boat cruise ing^ their rooms.for the past on the Hudson River. -

Re-Vue Chicago

January 2006 Re-Vue Chicago Happy New Year!! Pre-Vues: Guitar geek festival Ponderosa Stomp Re-Vues: DVD — Nightcourt USA CDs— Spo-Dee-O-Dee "The Many Sides Of…" The Round Up Boys “Good Lookin' Daddy" Saying Goodbye Closings: Passings: Berghoff Candy Barr Tiny Lounge James Austin Marshall Fields Trader vics City news James Dean Gallery As always News, reviews, Event Notices, Calendar And morE Inside this issue Re-Vue Another new year! The Re-Vue staff were primed and ready at the end of 2005 to start the fourth year for Re-Vue… then the Holidays struck and some of us did a little too much celebrating! So, the Re-Vue gang are EASING our way into 2006 with a no-frills issue. This month our most dedicated writers went forth into the farthest reaches of the city to bring you a look at what will be missing in Chicago this year. So many great places shuttered their doors in December and we wanted to do a little something to mourn their passing. Time-honored favorites like Marshall Fields, the fabulous Berghoff Restaurant (the oldest restaurant in the city will close its doors in February!!), and Trader Vics. We also felt that the time was right to take a woeful look back over all the celebrities that we lost in the last year. Col. Dan Sorenson started his own version of (pardon the expression) “death watch 2005” early last year. He complied a very comprehensive list of celebrities, has-beens, and the almost never-weres that passed on to the great beyond. -

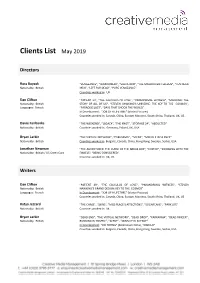

Clients List May 2019

Clients List May 2019 Directors Ross Boyask “VENGEANCE”, “WARRIORESS”, “SALVATION”, “THE MAGNIFICENT ELEVEN”, “TEN DEAD Nationality: British MEN”, “LEFT FOR DEAD”, “PURE VENGEANCE”. Countries worked in: UK Dan Clifton "PATIENT 39", "THE CALCULUS OF LOVE", "PARANORMAL WITNESS", "MANKIND: THE Nationality: British STORY OF ALL OF US", "STEVEN HAWKING'S UNIVERSE: THE KEY TO THE COSMOS", Languages: French “PARADISE LOST”, “DAYS THAT SHOOK THE WORLD”. In Development: “JOB OF A LIFETIME” (Vortex Pictures) Countries worked in: Canada, China, Europe, Morocco, South Africa, Thailand, UK, US.. Davie Fairbanks "THE WEEKEND", “LEGACY”, “THE KNOT”, “STORAGE 24”, “ABDUCTED” Nationality: British Countries worked in: Germany, Poland, UK, USA. Bryan Larkin “THE VIRTUAL NETWORK”, “PARKARMA”, “SCENE”, “MIRACLE IN SILENCE”. Nationality: British Countries worked in: Bulgaria, Canada, China, Hong Kong, Sweden, Serbia, USA Jonathan Newman "THE ADVENTURER: THE CURSE OF THE MIDAS BOX", "FOSTER", "SWINGING WITH THE Nationality: British / US Green Card FINKELS", "BEING CONSIDERED". Countries worked in: UK, US. Writers Dan Clifton "PATIENT 39", "THE CALCULUS OF LOVE", "PARANORMAL WITNESS", "STEVEN Nationality: British HAWKING'S GRAND DESIGN: KEY TO THE COSMOS". Languages: French In Development: “JOB OF A LIFETIME” (Vortex Pictures) Countries worked in: Canada, China, Europe, Morocco, South Africa, Thailand, UK, US.. Katya Jezzard "THE CHASE", "SKINS", "MISS PLACE'S AFFECTIONS", "SUGARCANE", "PARK LIFE". Nationality: British Countries worked in: UK. Bryan Larkin “DEAD