British TV Comedies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

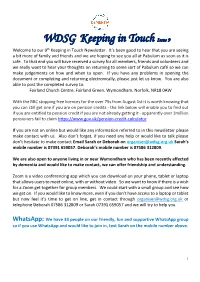

WDSG Keeping in Touch Newsletter, Issue 9

WDSG Keeping in Touch Issue 9 Welcome to our 9th Keeping in Touch Newsletter. It’s been good to hear that you are seeing a bit more of family and friends and we are hoping to see you all at Pabulum as soon as it is safe. To that end you will have received a survey for all members, friends and volunteers and we really want to hear your thoughts on returning to some sort of Pabulum café so we can make judgements on how and when to open. If you have any problems in opening the document or completing and returning electronically, please just let us know. You are also able to post the completed survey to: Fairland Church Centre, Fairland Green, Wymondham, Norfolk, NR18 0AW With the BBC stopping free licences for the over 75s from August 1st it is worth knowing that you can still get one if you are on pension credits - the link below will enable you to find out if you are entitled to pension credit if you are not already getting it - apparently over 1million pensioners fail to claim https://www.gov.uk/pension-credit-calculator If you are not on online but would like any information referred to in this newsletter please make contact with us. Also don’t forget, if you need any help or would like to talk please don’t hesitate to make contact Email Sarah or Deborah on [email protected] Sarah’s mobile number is 07391 659057. Deborah’s mobile number is 07586 312809. We are also open to anyone living in or near Wymondham who has been recently affected by dementia and would like to make contact, we can offer friendship and understanding. -

Quiz 1 Answers (.Pdf)

FMNH QUIZ 1 ANSWERS ANSWER GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 1 In 2013, Belgium issued stamps with which flavour Chocolate glue? 2 In which sport would you perform Randolphs and Trampolining Rudolphs? 3 For what is the UK tourist attraction Wookey Hole Caves famous? 4 Which fictional detective has museums devoted to him Sherlock in the Swiss towns of Lucens and Meiringen? Holmes 5 Which term is used for manufacturing or business Cottage carried out in people’s homes? Industry 6 In Norse mythology, what is the name of the rainbow Bifrost bridge connecting the gods’ world Asgard with man’s world Midgard? 7 The Duke of Edinburgh was born a prince of both Denmark Greece and which other country? 8 As what is hydrated magnesium sulphate better known? Epsom Salts 9 Which US space shuttle was the first to gain orbit in Columbia space? (1981) 10 In which country did the fandango originate? Spain LIVING WORLD ANSWER 1 What sort of creature is a fluke? Worm 2 What name is given to an organism that is both male Hermaphrodite and female? 3 What is a puffball? Fungus 4 How many pairs of ribs does a human have? 12 5 A pilchard is a member of which fish family? Herring 6 As what is a male honey bee known? Drone 7 What name is given to a body on which a parasite Host feeds? 8 What is the olfactory sense? Smell 9 What is the smallest living unit called? Cell 10 What do polled cattle not have? Horns ISLE OF MAN ANSWER 1 In 1079 King Godred Crovan defeated the Manx army Sky at where? 2 According to ‘The Gazetteer of the Isle of Man’, the Black Stream name Douglas is derived -

RUSSELL GASCOIGNE Current

RUSSELL GASCOIGNE Current: THE PASSENGER - delivered treatment and opening episode of three-part crime drama. THE GRIM CREEPERS – writing YA novel with series potential and A LONG WALK SIDEWAYS. AS THICK AS THIEVES – working on original feature screenplay with co-writer Philip Hughes (Thunderpants, I Want Candy) CROW’S WOOD – written outline for crime drama series set in 18th Century. ________________________________________________ TV A TOUCH OF FROST - wrote Private Lives commissioned by Excelsior/YTV. Top-rating drama with 16.85 million viewers starring David Jason, Peter Egan, Philip Jackson and Paloma Baeza. A TOUCH OF FROST – wrote Standards of Living commissioned by Excelsior/YTV. McCALLUM – wrote episode Beyond Good and Evil starring Nathaniel Parker, Eva Pope. Scottish Television. BODY STORY – dramatisations for 6-part science-drama-factual series combining drama with cutting-edge computer technology to show what happens inside the human body during a medical crisis or at different stages of life. Wall-to-Wall Television for Channel 4/Discovery Channel. Director Leanne Klein. Winner of a BMA Awards silver medal for Television Film. IRONMAN – single film outline about Victorian engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel commissioned by Ray Winstone’s company, Size 9 Productions (Steve Matthews) RHAG POB BRAD – wrote screenplay commissioned by BBC Wales/S4C starring Rhys Ifans. (Ruth Caleb) NIGHTSHIFT – wrote 3 x 30’ police drama series based on US series The Street for Portman Entertainment/BBC starring Rhys Ifans. FAMILY AFFAIRS – wrote two episodes of Channel 5 soap commissioned by TalkbackThames. THE BILL – episode commissioned by TalkbackThames. MONSIEUR REYNARD – wrote outline for series episode starring John Thaw as a priest in occupied France during WWII commissioned by Carlton Television. -

Guardian and Observer Editorial

Monday 01.01.07 Monday The year that changed our lives Swinging with Tony and Cherie Are you a malingerer? Television and radio 12A Shortcuts G2 01.01.07 The world may be coming to an end, but it’s not all bad news . The question First Person Are you really special he news just before Army has opened prospects of a too sick to work? The events that made Christmas that the settlement of a war that has 2006 unforgettable for . end of the world is caused more than 2 million people nigh was not, on the in the north of the country to fl ee. Or — and try to be honest here 4 Carl Carter, who met a surface, an edify- — have you just got “party fl u”? ing way to conclude the year. • Exploitative forms of labour are According to the Institute of Pay- wonderful woman, just Admittedly, we’ve got 5bn years under attack: former camel jockeys roll Professionals, whose mem- before she flew to the before the sun fi rst explodes in the United Arab Emirates are to bers have to calculate employees’ Are the Gibbs watching? . other side of the world and then implodes, sucking the be compensated to the tune of sick pay, December 27 — the fi rst a new year’s kiss for Cherie earth into oblivion, but new year $9m, and Calcutta has banned day back at work after Christmas 7 Karina Kelly, 5,000,002,007 promises to be rickshaw pullers. That just leaves — and January 2 are the top days 16 and pregnant bleak. -

Fawlty Towers - Episode Guide

Performances October 6, 7, 8, 13, 14, 15 Three episodes of the classic TV series are brought to life on stage. Written by John Cleese & Connie Booth. Music by Dennis Wilson By Special Arrangement With Samuel French and Origin Theatrical Auditions Saturday June 18, Sunday June 19 Thurgoona Community Centre 10 Kosciuszko Road, Thurgoona NSW 2640 Director: Alex 0410 933 582 FAWLTY TOWERS - EPISODE GUIDE ACT ONE – THE GERMANS Sybil is in hospital for her ingrowing toenail. “Perhaps they'll have it mounted for me,” mutters Basil as he tries to cope during her absence. The fire-drill ends in chaos with Basil knocked out by the moose’s head in the lobby. The deranged host then encounters the Germans and tells them the “truth” about their Fatherland… ACT TWO – COMMUNICATION PROBLEMS It’s not a wise man who entrusts his furtive winnings on the horses to an absent-minded geriatric Major, but Basil was never known for that quality. Parting with those ill-gotten gains was Basil’s first mistake; his second was to tangle with the intermittently deaf Mrs Richards. ACT THREE – WALDORF SALAD Mine host's penny-pinching catches up with him as an American guest demands the quality of service not normally associated with the “Torquay Riviera”, as Basil calls his neck of the woods. A Waldorf Salad is not part of Fawlty Towers' standard culinary repertoire, nor is a Screwdriver to be found on the hotel's drinks list… FAWLTY TOWERS – THE REGULARS BASIL FAWLTY (John Cleese) The hotel manager from hell, Basil seems convinced that Fawlty Towers would be a top-rate establishment, if only he didn't have to bother with the guests. -

How Does Context Shape Comedy As a Successful Social Criticism As Demonstrated by Eddie Murphy’S SNL Sketch “White Like Me?”

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2012 How Does Context Shape Comedy as a Successful Social Criticism as Demonstrated by Eddie Murphy’s SNL Sketch “White Like Me?” Abigail Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Abigail, "How Does Context Shape Comedy as a Successful Social Criticism as Demonstrated by Eddie Murphy’s SNL Sketch “White Like Me?”" (2012). Honors College. 58. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/58 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW DOES CONTEXT SHAPE COMEDY AS A SUCCESSFUL SOCIAL CRITICISM AS DEMONSTRATED BY EDDIE MURPHY’S SNL SKETCH “WHITE LIKE ME?” by Abigail Jones A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Communications) The Honors College University of Maine May 2012 Advisory Committee: Nathan E. Stormer, Professor of Communication, Advisor Kristin M. Langellier, Professor of Communication Sandra Hardy, Associate Professor of Theater Mimi Killinger, Honors College Rezendes Preceptor for the Arts Adam Kuykendall, Marketing Manager for the School of Performing Arts Abstract This thesis explores the theory of comedy as social criticism through an interpretive investigation. For comedy to be a potent criticism it is important for the audience to understand the context surrounding the sketch. Without understanding the context the sketch still has the ability to be humorous, but the critique is harder to acknowledge. -

+14 Days of Tv Listings Free

CINEMA VOD SPORTS TECH + 14 DAYS OF TV LISTINGS 1 JUNE 2015 ISSUE 2 TVGUIDE.CO.UK TVDAILY.COM Jurassic World Orange is the New Black Formula 1 Addictive Apps FREE 1 JUNE 2015 Issue 2 Contents TVGUIDE.CO.UK TVDAILY.COM EDITOR’S LETTER 4 Latest TV News 17 Food We are living in a The biggest news from the world of television. Your television dinners sorted with revolutionary age for inspiration from our favourite dramas. television. Not only is the way we watch television being challenged by the emergence of video on 18 Travel demand, but what we watch on television is Journey to the dizzying desert of Dorne or becoming increasingly take a trip to see the stunning setting of diverse and, thankfully, starting to catch up with Downton Abbey. real world demographics. With Orange Is The New Black back for another run on Netflix this month, we 19 Fashion decided to celebrate the 6 Top 100 WTF Steal some shadespiration from the arduous journey it’s taken to get to where we are in coolest sunglass-wearing dudes on TV. 2015 (p14). We still have a Moments (Part 2) long way to go, but we’re The final countdown of the most unbelievable getting there. Sports Susan Brett, Editor scenes ever to grace the small screen, 20 including the electrifying number one. All you need to know about the upcoming TVGuide.co.uk Formula 1 and MotoGP races. 104-08 Oxford Street, London, W1D 1LP [email protected] 8 Cinema CONTENT 22 Addictive Apps Editor: Susan Brett Everything you need to know about what’s Deputy Editor: Ally Russell A handy guide to all the best apps for Artistic Director: Francisco on at the Box Office right now. -

COM FT 316 Syllabus SP13

Boston University Study Abroad London British Film and TV Since 1960 COM FT 316 (Core Course) Spring 2013 Instructor Information A. Name Dr Christine Fanthome and Dr Nick Haeffner Course Description This course aims to provide students with an overview of media in Britain within a social context. Special emphasis is placed on the relationship between media, citizenship and democracy in the context of post-War British society. Consideration will also be given to the relationship between British and US media culture. Methodology Each teaching session will involve a lecture, illustrative material and a class discussion based on the set reading. Students should absorb as much film and television as they can out of class in order to participate fully in seminar discussions. **Please note: no laptops to be used in class. Course Objectives By the end of the course students will able to: • Understand the cultural context of British film and TV since the 1960s. • Show awareness of the international economic underpinnings of these industries • Consider the role of politics in media production, distribution and consumption • Show awareness of historical controversies surrounding British film and TV’s relationship to the US • Conduct their own research in the field Textbooks/Supplies You can read selected chapters online at https://lms.bu.edu (you must be logged in using your Kerberos username/password to view materials). Assessment Essay 50% graded (by Dr Christine Fanthome) Exam 50% graded (by Dr Nick Haeffner) Report: This should consist of a 2,000-word essay on a topic covered in class (details to follow from Dr Fanthome). -

American Comedy in Three Centuries the Contras4 Fashion, Calzforniα Suile

American Comedy in Three CenturieS The Contras4 Fashion, Calzforniα Suile James R. Bowers Abstract This paper is a survey of the development of American comedy since the United States became an independent nation. A representative play was selected from the 18th century(Royall Tyler’s The Contrast), the 19th century(Anna Cora Mowatt’s Fashion)and the 20th century(Neil Simon’s Califoグnia Suite). Asummary of each play is丘rst presented and then fo110wed by an analysis to determine in what ways it meets or deviates from W. D, Howarth’s minimal de且nition of comedy. Each work was found to conform to the definition and to possess features su岱ciently distinct for it to be classified as a masterpiece of its time. Next, the works were analyzed to derive from them unique features of American comedy. The plays were found to possess distinctive elements of theme, form and technique which serve to distinguish them as Ameri. can comedies rather than Europeal1, Two of these elelnents, a thematic concern with identity as Americans and the technical primacy of dialog and repartee for the stimulation of laughter were found to persist into present day comedy. Other elements:characterization, subtlety of form -145一 and social relevance of theme were 6bserved to have evolved over the centuries into more complex modes. Finally, it was noted that although the dominant form of comedy iロthe 18th and 19th centuries was an American variant of the comedy of man- ners, the 20th century representative Neil Simon seems to be evolving a new form I have coined the comedy -

The Good Guys Tweed Heads South Celebrate Australia

.HHSLQJLWLQWKH THE TWEED )DPLO\ Volume 3 #20 Thursday, January 27, 2011 Advertising and news enquiries: Phone: (02) 6672 2280 [email protected] [email protected] The family behind the business www.tweedecho.com.au LOCAL & INDEPENDENT Page 8 Rose, Biosphere status Young urged for Tweed Achiever Murray Simpson the McPherson and Border ranges and possibly even the marine reserve A grand plan to have the Tweed Val- off Byron Bay. ley declared a ‘biosphere reserve’ has It will spill from Tweed shire to By- using her been launched by the Caldera Envi- ron, Lismore, Kyogle and Northern ronment Centre. Rivers shire councils and will link But it has nothing to do with Dis- with Queensland’s scenic rim scheme brains neyland-type glass bubbles, says co- which runs down to the border. ordinator Edward ‘Hop. e’ Hopkins. ‘It all centres on the biodiversity ‘We want to become part of a global hot-spot we have where the McPher- network of biospheres promoted by son and Border ranges meet roughly UNESCO,’ he said. at the head of the Limpinwood Valley,’ ‘There are 546 biospheres world- he said. wide in 109 countries and 15 in Aus- Rarest of the rare tralia. ‘We’re looking at biosphere status ‘We’ve got species there that exist Murray Simpson received a Year 12 Rotary prize for cit- Mr McDonald received recogni- for the Border Ranges and Noosa to nowhere else.’ izenship and the Defence Force Long tion for his services to the cattle in- provide a green belt, or lungs, at either The roots of the biosphere reserve The strange world of teenagers’ brains Tan leadership and teamwork award. -

Individual Dog Records at Group Level

GROUP JUDGING: 1988-2007 DATA: SHO-YR = CKC SHOW NUMBER #B =NUMBER OF DOGS AT BREED LEVEL #GR=NUMBER OF DOGS AT GROUP LEVEL #SHO=NUMBER OF DOGS IN SHOW P = GROUP PLACEMENT (1-4; 0=NONE) BIS=BEST IN SHOW (1=BIS; 0=NONE) NDD=NUMBER OF DOGS DEFEATED DOG: Kailasa Full Moon SHO- YR #B #GR #SHO P BIS NDD JUDGE 1- 88 1 16 187 0 0 0 Mrs.C.Debruyne (Rockland,ON) 2- 88 1 15 184 4 0 10 Mrs.D.Marsh (Victoria,BC) 80- 88 9 24 224 3 0 21 Mrs.J.Brazier (Vancouver,BC) 3 TIMES JUDGING WITH 2 PLACEMENTS = 66.7% DOG: Ch. Shente's Christian Dior SHO- YR #B #GR #SHO P BIS NDD JUDGE 3- 88 9 51 383 1 1 382 Mr.Q.LaHam (Daly City,CA) 4- 88 9 58 457 1 1 456 Mr.L.T.Haverstock (Lamont,AB) 5- 88 7 50 416 1 0 49 Ms.M.Billings (Ft.Lauderdale,FL) 14- 88 11 74 561 1 0 73 Mr.A.Warnock (London,ON) 15- 88 11 77 704 2 0 67 Mrs.K.Guimond (Mississauga,ON) 21- 88 10 20 280 1 1 279 Mrs.B.McHugh (Oshawa,ON) 22- 88 10 28 343 1 0 27 Mrs.S.Loftus (Vancouver,BC) 23- 88 9 27 333 1 0 26 Ms.H.Logan (Campbellville,ON) 30- 88 7 74 489 1 0 73 Mr.E.Croad (Auckland,NZ) 31- 88 8 71 480 1 0 70 Mrs.D.Kodner (Highland Park,IL) 35- 88 13 65 602 1 0 64 Mr.J.Connolly (Gibralter,MI) 36- 88 19 69 729 1 0 68 Mrs.J.Moulton (Surrey,BC) 37- 88 14 67 614 1 1 613 Mr.N.Aubrey-Jones (Montreal,PQ) 42- 88 8 68 507 1 0 67 Mr.E.R.Dixon (Toronto,ON) 43- 88 8 87 708 1 1 707 Ms.M.Billings (Ft.Lauderdale,FL) 44- 88 8 75 651 1 0 74 Mr.G.Payton (Vancouver,BC) 74- 88 13 86 691 1 0 85 Mr.G.Edwards (Acton,ON) 75- 88 17 94 657 1 0 93 Mrs.J.Nattrass (Pickering,ON) 91- 88 6 49 349 1 1 348 Mr.Q.LaHam (Daly City,CA) 92- 88 -

BBC Oral History Collection, Transcript, Robin Scott

ORAL HISTORY OF THE BBC: ROBIN SC INTERVIEWED BY FRANK GILLARD. SECOND SESSION RECORDED IN BROADCASTING HOUSE, LONDON, 14th January 1981. GILLARD: Let's move on now to the period you spent, quite a brief period really but a very important one, in Radio in the second half of the sixties, when you became Controller Radio 1 8 2. Tell us first of all how the job came to you and forget that I'm here. SCOTT: I had after some three years, three and a half years or so, back with Television Outside Broadcasts, I'd become, not discontented with the job I was doing, but really felt that if I was to realise what I believed to be my potential I should look for an executive position somewhere in the BBC. And thought well why not go back to my first love which was after all Radio, and so I applied for the job of assistant head of Gramophone Department in Broadcasting House. Working therefore to Anna Instone who was Head of the Department for many years, a great many. And I duly applied for this job although it was not at a grade above my own, in fact I don't think it certainly didn't produce any more money, but I wanted in fact to get onto the rung of a different ladder, possibly. I also wanted to get into domestic radio broadcasting which I'd really only contributed programmes to but never enjoyed any kind of executive position, or producer position, having always in radio worked at Bush House.