Desperate Times, Desperate Measures Desperate Times, Alexander B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The US Army Air Forces in WWII

DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES AIR FORCE Air Force Historical Studies Office 28 June 2011 Errata Sheet for the Air Force History and Museum Program publication: With Courage: the United States Army Air Forces in WWII, 1994, by Bernard C. Nalty, John F. Shiner, and George M. Watson. Page 215 Correct: Second Lieutenant Lloyd D. Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 218 Correct Lieutenant Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 357 Correct Hughes, Lloyd D., 215, 218 To: Hughes, Lloyd H., 215, 218 Foreword In the last decade of the twentieth century, the United States Air Force commemorates two significant benchmarks in its heritage. The first is the occasion for the publication of this book, a tribute to the men and women who served in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War 11. The four years between 1991 and 1995 mark the fiftieth anniversary cycle of events in which the nation raised and trained an air armada and com- mitted it to operations on a scale unknown to that time. With Courage: U.S.Army Air Forces in World War ZZ retells the story of sacrifice, valor, and achievements in air campaigns against tough, determined adversaries. It describes the development of a uniquely American doctrine for the application of air power against an opponent's key industries and centers of national life, a doctrine whose legacy today is the Global Reach - Global Power strategic planning framework of the modern U.S. Air Force. The narrative integrates aspects of strategic intelligence, logistics, technology, and leadership to offer a full yet concise account of the contributions of American air power to victory in that war. -

Civil Defense and Chemical Warfare in Great Britain, 1915-1945 Jordan I

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-7-2018 Britain Can Take It: Civil Defense and Chemical Warfare in Great Britain, 1915-1945 Jordan I. Malfoy [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC006585 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Military History Commons, Political History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Malfoy, Jordan I., "Britain Can Take It: Civil Defense and Chemical Warfare in Great Britain, 1915-1945" (2018). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3639. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3639 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida BRITAIN CAN TAKE IT: CHEMICAL WARFARE AND THE ORIGINS OF CIVIL DEFENSE IN GREAT BRITAIN, 1915 - 1945 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by Jordan Malfoy 2018 To: Dean John F. Stack, Jr. choose the name of dean of your college/school Green School of International and Public Affairs choose the name of your college/school This disserta tion, writte n by Jordan Malfoy, and entitled Britain Can Take It: Chemical Warfare and the Ori gins of Civil D efense i n Great Britain, 1915-1945, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. -

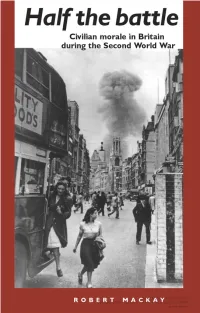

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM Via Free Access HALF the BATTLE

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access HALF THE BATTLE Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 1 16/09/02, 09:21 Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 2 16/09/02, 09:21 HALF THE BATTLE Civilian morale in Britain during the Second World War ROBERT MACKAY Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 3 16/09/02, 09:21 Copyright © Robert Mackay 2002 The right of Robert Mackay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 5893 7 hardback 0 7190 5894 5 paperback First published 2002 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset by Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs. -

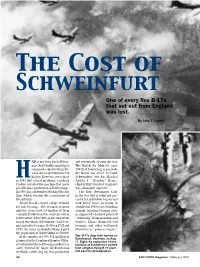

The Cost of H

The Cost of Schweinfurt One of every five B-17s that set out from England was lost. By John T. Correll ad it not been for ball bear- and potentially shorten the war. ings, Schweinfurt might have The British Air Ministry since remained a small town in Ba- 1943 had been trying to persuade varia and escaped the notice of the Royal Air Force to bomb history. However, it was there Schwein furt, but Air Marshal in 1883 that a local mechanic, Friedrich Arthur T. “Bomber” Harris, HFischer, invented the machine that made chief of RAF Bomber Command, possible mass production of ball bearings. was adamantly opposed. In 1906, his son founded the Kugelfischer The RAF determined early firm, which became the cornerstone of in the war that it could not pre- the industry. cisely hit individual targets and World War II created a huge demand took heavy losses in trying. It for ball bearings. The German aviation switched in 1942 to area bombing industry alone used 2.4 million of them at night, targeting German cities a month. Production was concentrated in in support of a national policy of Schweinfurt, where five plants turned out “dehousing” German citizens and nearly two-thirds of Germany’s ball bear- workers. Harris dismissed ball ings and roller bearings. Between 1922 and bearings and other bottleneck 1943, the surge in manufacturing tripled objectives as “panacea targets.” the population of Schweinfurt to 50,000. In the summer of 1943, US and British Top: B-17s drop their bombs on Schweinfurt, Germany, on Aug. planners for the Combined Bomber Offen- 17. -

Strategic Bombing, the Nuclear Revolution, and City Busting

STRATEGIC BOMBING, THE NUCLEAR REVOLUTION, AND CITY BUSTING A presentation by Henry Sokolski Executive Director Nonproliferation Policy Education Center www.npolicy.org The Institute of World Politics June 11, 2013 1 QUESTIONS TO BE ANSWERED I. How was city busting viewed and done before and during WWII? II. The nuclear weapons revolution: How militarily significant was it? III. Why, initially, did developing ever larger nuclear weapons seem logical? IV. Precision Guidance: How did its advent constitute a counter revolution and how has it affected nuclear weapons deployments? V. City busting: Why might its morality still be an issue today? 6/11/2013 2 UNTIL MODERNITY, TARGETING CITIES WAS FROWNED UPON Sun Tzu, The Art of War, 500 BC “To subdue the enemy without fighting is the supreme excellence. Thus, what is of supreme importance in war is to attack the enemy’s strategy. Next best is to disrupt his alliances by diplomacy. The next best is to attack his army. And the worst policy is to attack cities.” 3 SHERMAN’S MARCH TO THE SEA: PRECURSOR TO CITY BUSTING 4 Atlanta, Georgia AMERICAN CIVIL WAR Field Artillery and Fire A six-month campaign Few if any civilians killed Residences, churches, and hospitals spared 5 FRENCH SUBMARINE WARFARE THEORY: FIRST MODERN MUSINGS ON STRATEGIC WEAPONRY 6 FRENCH HOPED SUBMARINES MIGHT HELP NEUTRALIZE UK & ITS FLEET BY BLOCKADE Gymnote class Narval 7 Gustave Zede class Sirene class EVEN UNRESTRICTED SUB WARFARE IN WWI, THOUGH, HAD MIXED RESULTS 8 WORLD WAR I TRENCH WARFARE: ITS HORRORS REKINDLED INTEREST -

So, 391--G2, 394; in First World War 378; Anti-Submarine Weapons 378

Index 1053 So, 391--g2, 394; in First World War 378; Baker fitted to Lancaster x 758; Rose anti-submarine weapons 378--g, 393-4; U 685, 752-3; Village Inn/AGLT and radar boat losses 378-9, 394-5, 396, 399, 405, assisted gun-laying 752-3, 823; need to 414, 416; Allied shipping losses 379, 405, counter Schrage Musik fitted to German 414; U-boat tactics 381 , 391 , 396, 404- 5, night-fighters 687-8, 734, 763-4, 830, 854 409, 412; Mooring patrols 383, 402-4, Army Co-operation Command, see 410-1 l; Leigh Light 393- 4, 395; Biscay commands offensive 393-8; ASV radar and counter Army Photo Interpretation Section: and measures, 393- 4, 395; Musketry patrols procedures for photographic 397-8, 446; Percussion operations 398; in reconnaissance 296-7 Operation Overlord 406-ro; inshore Arnhem 326, 347-8, 875-6, 881 - 3, 890 patrols 410-16; Sir Arthur Harris believes Arnold, Gen. H.H. 832 bomber offensive is more important 598, Arnold-Portal-Towers agreement: and supply 638; Portal agrees 620; Bomber Command of bomber aircraft 599 ordered to attack U-boat bases in France Arras 775, 808 638--g, 677; other refs 95, 270, 375 Article xv, see Canadianization Anti-U-boat Warfare Committee 391 , 394 Ash, P/O W.F. 207 Antwerp 327, 337, 835, 845, 855 Ashford, F/L Herbert 648 Anzio 287-8 Ashman, W/C R.A. 400 Aqualagna 308 Assam 876, 905 Arakan 901, 903, 906 Associated Press 71 Archer, w/c J.C. 398, 400 ASV , see radar, air-to-surface vessel (ASV) Archer, F/L P.L.I. -

The Evolution of Strategy

This page intentionally left blank The Evolution of Strategy Is there a ‘Western way of war’ which pursues battles of annihilation and single-minded military victory? Is warfare on a path to ever greater destructive force? This magisterial new account answers these questions by tracing the history of Western thinking about strategy – the employ- ment of military force as a political instrument – from antiquity to the present day. Assessing sources from Vegetius to contemporary America, and with a particular focus on strategy since the Napoleonic Wars, Beatrice Heuser explores the evolution of strategic thought, the social institutions, norms and patterns of behaviour within which it operates, the policies that guide it and the culture that influences it. Ranging across technology and warfare, total warfare and small wars as well as land, sea, air and nuclear warfare, she demonstrates that warfare and strategic thinking have fluctuated wildly in their aims, intensity, limitations and excesses over the past two millennia. beatrice heuser holds the Chair of International History at the School of Politics and International Relations, University of Reading. Her publications include Reading Clausewitz (2002); Nuclear Mentalities? (1998) and Nuclear Strategies and Forces for Europe, 1949-2000 (1997), both on nuclear issues in NATO as a whole, and Britain, France, and Germany in particular. The Evolution of Strategy Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present Beatrice Heuser cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521155243 © Beatrice Heuser 2010 This publication is in copyright. -

British Strategic Bombing Benjamin Joyner Benjamin Joyner, From

142 Joyner British Strategic Bombing Ironically, Britain would soon pass through the crucible of modern strategic bombing herself. Benjamin Joyner British experience in the Blitz Benjamin Joyner, from Equality, Illinois, earned his BA in History in 2010 with a The German strategic bombing campaign against the British was the first minor in Political Science. The former homeschooler is entering graduate school in massive application of Douhet’s ideas in a modern war involving western fall 2010 to pursue a MA in History. This paper was written as a sophomore in nations. The “Battle of Britain” lasted from July 10th 1940 through fall 2008 for HIS 3420 (World War II) for Dr. Anita Shelton. December 31st of the same year. The first part of this massive bombardment focused on destroying the RAF, but on September 9th the focus shifted to _____________________________________________________________ major cities and urban centers. The goal of the Germans was to remove the British from the war by breaking the civilian will to fight. This change in targets and objectives came to be known as the Blitz. During this time The British strategic bombing campaigns against Germany during the English cities such as Belfast, Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Clydebank, Second World War have been a topic of much discussion and debate over Coventry, Greenock, Sheffield, Swansea, Liverpool, Hull, Manchester, the years. Initially seen as a way to minimize the loss of Allied lives while Portsmouth, Plymouth, Nottingham and Southampton were all targeted by putting great pressure on the Germans, some historians see the British the Luftwaffe and suffered heavy casualties. -

None but the Brave

None but the Brave None but the Brave provides a fresh look at the Allied bombing but campaign against the European Axis powers during the Second None the Brave World War. This bombing of the Third Reich and its allies was THE ESSENTIAL CONTRIBUTIONS OF RAF BOMBER COMMAND part of Britain’s overall war strategy to take the offensive to TO ALLIED VICTORY DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR the enemy. In doing so, it created a ‘second front’ that bled off resources from the enemy’s campaign against the Soviets, and it required massive amounts of manpower and materiel to be diverted from the primary war efforts to both confront the threat and to address the damage sustained. It dealt telling blows to the Axis economic and industrial infrastructure, forcing the decentralization of its war industries. Finally, it helped pave the way, through destruction of enemy air defence assets, oil resources, and transportation networks, for a successful invasion of Germany through northwest Europe. The book is also a celebration of the aircrew experience and the essential resolve and fortitude that was demonstrated by these campaigners throughout the conflict, in the face of frequently daunting perils and odds against survival. Bashow David L. Bashow but None the Brave but None the Brave THE ESSENTIAL CONTRIBUTIONS OF RAF BOMBER COMMAND TO ALLIED VICTORY DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR BY DAVID L. BASHOW Copyright © 2009 Her Majesty the Queen, in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of National Defence. Canadian Defence Academy Press PO Box 17000 Stn Forces Kingston, Ontario K7K 7B4 Produced for the Canadian Defence Academy Press by 17 Wing Winnipeg Publishing Office. -

Weir, Paul.Pdf

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details BRITISH ATTITUDES TO THE AERIAL BOMBARDMENT OF GERMAN CITIES DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR PAUL WEIR PHD UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX SEPTEMBER 2014 2 Statement I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. However, the thesis incorporates to the extent indicated below, material already submitted as part of required coursework and/or for the degree of Master of Arts in Modern European History which was awarded by the University of Sussex. Signature: Chapter Four, entitled: “‘A city of the dead’: Dresden and the end of the war”, is a reworked version of my Master of Arts dissertation, completed in 2008. The version included here incorporates original research carried out during my current period of registration at the University of Sussex. The argument has been substantially developed to situate this part of my research within the broader scope of my thesis. -

Daylight Precision Bombing, a Bomb Into a Pickle Barrel from High Ing Altitude of 15,000 Feet Instead of Developed in the 1930S at the Air Corps Altitude

A basic belief of the Army Air Forces was severely tested in the skies over Germany and Japan. Daylight Precision Bombing By John T. Correll n the aviation enthusiasm of the age score for an Air Corps bombardier The pickle barrel story, often told and 1930s, it was popular to claim that was a circular error of 400 feet, and widely believed, served to reinforce the I Air Corps bombardiers could drop that was from the relatively forgiv- theory of daylight precision bombing, a bomb into a pickle barrel from high ing altitude of 15,000 feet instead of developed in the 1930s at the Air Corps altitude. In 1940, Theodore H. Barth, 30,000. Tactical School at Maxwell Field, Ala. president of Carl L. Norden Inc., said that Nobody knows for sure where the The theory rejected the previously “we do not regard a 15-foot square ... as “pickle barrel” imagery began. The prevailing strategy of bombing broad being a very difficult target to hit from term may have been coined by Norden’s areas, more or less indiscriminately, and an altitude of 30,000 feet,” provided the Barth, who was among its most energetic focused on specific targets of military bombardier was using that company’s popularizers. Norden was not alone in significance. As a side benefit, precision new M-4 bombsight connected to an spreading the legend. Some Air Force bombing would avoid civilian casualties autopilot. bombardiers spoke proudly of tossing and limit collateral damage. That was stretching it considerably. bombs into a 100-foot circle from four The Army Air Forces was the lone In everyday practice in 1940, the aver- miles up. -

The Air Campaign: John Warden and the Classical Airpower Theorists By

The Air Campaign John Warden and the Classical Airpower Theorists DAVID R. METS Revised Edition Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 1999 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mets, David R. The air campaign : John Warden and the classical airpower theorists / David R. Mets. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Air power. 2. Air warfare. 3. Military planning. 4. Warden, John A., 1943– . I. Title UG630.M37797 1998 358.4—dc21 98-33838 CIP Revised April 1999 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii FOREWORD . v ABOUT THE AUTHOR . vii PREFACE . ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . xi 1 THE CONTEXT: A DIFFERENT MIND-SET . 1 The Mind-Set in World War I . 1 Post-World War I Posture . 4 Notes . 8 2 GIULIO DOUHET . 11 A Continental Theorist . 11 Organization for War . 14 Impact . 15 Notes . 18 3 HUGH TRENCHARD . 21 British Empire Theorist . 21 Organization for War . 23 Notes . 29 4 WILLIAM MITCHELL . 31 New World Theorist . 31 Organization for War . 37 Notes . 50 5 JOHN WARDEN . 55 Theorist or Throwback? . 55 Organization for War . 62 Notes . 69 iii Chapter Page 6 CONCLUSIONS . 73 Notes . 79 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 81 INDEX . 85 Photographs Gen Billy Mitchell and Gen Mason M. Patrick . 32 Gen James Doolittle . 35 USS Saratoga . 41 Gen Oscar Westover . 45 Gen Frank Andrews .