Download Policy Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Thesis Or Dissertation As A

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature: _____________________________ ________________ Ryan Tans Date Decentralization and the Politics of Local Taxation in Southeast Asia By Ryan Tans Doctor of Philosophy Political Science _________________________________________ Richard F. Doner Advisor _________________________________________ Jennifer Gandhi Committee Member _________________________________________ Douglas Kammen Committee Member _________________________________________ Eric R. Reinhardt Committee Member Accepted: _________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies ___________________ Date Decentralization and the Politics of Local Taxation in Southeast Asia By Ryan Tans M.A., Emory University, 2015 M.A., National University of Singapore, 2011 B.A., Calvin College, 2004 Advisor: -

Macrofouler Community Succession in South Harbor, Manila Bay, Luzon Island, Philippines During the Northeast Monsoon Season of 2017–2018

Philippine Journal of Science 148 (3): 441-456, September 2019 ISSN 0031 - 7683 Date Received: 26 Mar 2019 Macrofouler Community Succession in South Harbor, Manila Bay, Luzon Island, Philippines during the Northeast Monsoon Season of 2017–2018 Claire B. Trinidad1, Rafael Lorenzo G. Valenzuela1, Melody Anne B. Ocampo1, and Benjamin M. Vallejo, Jr.2,3* 1Department of Biology, College of Arts and Sciences, University of the Philippines Manila, Padre Faura Street, Ermita, Manila 1000 Philippines 2Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology, College of Science, University of the Philippines Diliman, Diliman, Quezon City 1101 Philippines 3Science and Society Program, College of Science, University of the Philippines Diliman, Diliman, Quezon City 1101 Philippines Manila Bay is one of the most important bodies of water in the Philippines. Within it is the Port of Manila South Harbor, which receives international vessels that could carry non-indigenous macrofouling species. This study describes the species composition of the macrofouling community in South Harbor, Manila Bay during the northeast monsoon season. Nine fouler collectors designed by the North Pacific Marine Sciences Organization (PICES) were submerged in each of five sampling points in Manila Bay on 06 Oct 2017. Three collection plates from each of the five sites were retrieved every four weeks until 06 Feb 2018. Identification was done via morphological and CO1 gene analysis. A total of 18,830 organisms were classified into 17 families. For the first two months, Amphibalanus amphitrite was the most abundant taxon; in succeeding months, polychaetes became the most abundant. This shift in abundance was attributed to intraspecific competition within barnacles and the recruitment of polychaetes. -

Part Ii Metro Manila and Its 200Km Radius Sphere

PART II METRO MANILA AND ITS 200KM RADIUS SPHERE CHAPTER 7 GENERAL PROFILE OF THE STUDY AREA CHAPTER 7 GENERAL PROFILE OF THE STUDY AREA 7.1 PHYSICAL PROFILE The area defined by a sphere of 200 km radius from Metro Manila is bordered on the northern part by portions of Region I and II, and for its greater part, by Region III. Region III, also known as the reconfigured Central Luzon Region due to the inclusion of the province of Aurora, has the largest contiguous lowland area in the country. Its total land area of 1.8 million hectares is 6.1 percent of the total land area in the country. Of all the regions in the country, it is closest to Metro Manila. The southern part of the sphere is bound by the provinces of Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal, and Quezon, all of which comprise Region IV-A, also known as CALABARZON. 7.1.1 Geomorphological Units The prevailing landforms in Central Luzon can be described as a large basin surrounded by mountain ranges on three sides. On its northern boundary, the Caraballo and Sierra Madre mountain ranges separate it from the provinces of Pangasinan and Nueva Vizcaya. In the eastern section, the Sierra Madre mountain range traverses the length of Aurora, Nueva Ecija and Bulacan. The Zambales mountains separates the central plains from the urban areas of Zambales at the western side. The region’s major drainage networks discharge to Lingayen Gulf in the northwest, Manila Bay in the south, the Pacific Ocean in the east, and the China Sea in the west. -

Accomplishment Report 1St Quarter 2017

ACCOMPLISHMENT REPORT ST 1 QUARTER 2017 PROGRAM / ACTIVITY / PROJECT STATUS OBJECTIVES Present Status of Program/Follow-ups: Title of Program/Activity/Project; Inclusive Dates; Venue; Nature of Activity (if not indicated Objectives of the Program/Activity/Project Completed/Ongoing/Cancelled/Rescheduled in the title); Short Description (please provide reason for non-implementation) I. BROCHURE SUPPORT OF DOT OSAKA FOR OSAKA, NAGOYA AND FUKUOKA TRAVEL AGENCIES Inclusive Dates: 01 October 2016 to 30 March 2017 Brochure support Venue: Osaka, Nagoya, Fukuoka (Japan) Nature of Activity: Joint Promotion Short Description: DOT Osaka has reiterated the importance of brochure support based on the Japan Travel Bureau (JTB) Report 2016: All About Japanese Overseas Travelers (red book) as follows: #1 Reason for choosing a travel destination is based on reading a Completed pamphlet/brochure #2 Reason is recommended by family members and friends #3 Reason is recommendation from a travel firm Further, the #3 reason on the importance of brochure support is also a manifestation of the goodwill maintained with the trade partners in West Japan. The brochures will be distributed from October 2016 until March 2017. II. BID PRESENTATION OF FIABCI PHILS IN ITS BID TO HOST THE 2020 FIABCI WORLD CONGRESS 1 ACCOMPLISHMENT REPORT ST 1 QUARTER 2017 PROGRAM / ACTIVITY / PROJECT STATUS OBJECTIVES Present Status of Program/Follow-ups: Title of Program/Activity/Project; Inclusive Dates; Venue; Nature of Activity (if not indicated Objectives of the Program/Activity/Project Completed/Ongoing/Cancelled/Rescheduled in the title); Short Description (please provide reason for non-implementation) Inclusive Dates: 23 December 2016 to 06 January 2017 Venue: N/A Nature of Activity: Logo / Photo / Video Support Completed Short Description: Video of Philippine Destinations to be included in the presentation to the FIABCI Officers in connection with the Philippines Bid to host the 2020 International Real Estate Federation World Congress. -

Iloilo Provincial Profile 2012

PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile TIUY Research and Statistics Section i Provincial Planning and Development Office PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile P R E F A C E The Annual Iloilo Provincial Profile is one of the endeavors of the Provincial Planning and Development Office. This publication provides a description of the geography, the population, and economy of the province and is designed to principally provide basic reference material as a backdrop for assessing future developments and is specifically intended to guide and provide data/information to development planners, policy makers, researchers, private individuals as well as potential investors. This publication is a compendium of secondary socio-economic indicators yearly collected and gathered from various National Government Agencies, Iloilo Provincial Government Offices and other private institutions. Emphasis is also given on providing data from a standard set of indicators which has been publish on past profiles. This is to ensure compatibility in the comparison and analysis of information found therewith. The data references contained herewith are in the form of tables, charts, graphs and maps based on the latest data gathered from different agencies. For more information, please contact the Research and Statistics Section, Provincial Planning & Development Office of the Province of Iloilo at 3rd Floor, Iloilo Provincial Capitol, and Iloilo City with telephone nos. (033) 335-1884 to 85, (033) 509-5091, (Fax) 335-8008 or e-mail us at [email protected] or [email protected]. You can also visit our website at www.iloilo.gov.ph. Research and Statistics Section ii Provincial Planning and Development Office PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile Republic of the Philippines Province of Iloilo Message of the Governor am proud to say that reform and change has become a reality in the Iloilo Provincial Government. -

ICTSI Opens Its PNG Terminals CGSA Strengthens Market Position PM O’Neill Special Guest at Motukea Rites Gets Gov’T Approval to Handle Mega Vessels

Vol. 28, Issue N.º 07 July 2018 The Official Publication of International Container Terminal Services, Inc. .com ictsi www. ICTSI opens its PNG terminals CGSA strengthens market position PM O’Neill special guest at Motukea rites gets gov’t approval to handle mega vessels International Container Terminal Services, Inc. (ICTSI) has International Container Terminal Services, Inc.’s (ICTSI) largest opened its terminals in Papua New Guinea–Motukea International port concession in the Americas, Contecon Guayaquil SA (CGSA), further strengthened its market position as the main trading gateway Terminal (MIT) in the capital Port Moresby and Lae Tidal Basin in the entire Ecuador after recently getting the government’s nod to in Morobe Province–bringing ICTSI’s portfolio to 30 ports. service larger vessels. GLOBAL OPERATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 04 ICTSI opens its PNG terminals 09 YICTL names new officers 06 CGSA strengthens market position PICT holds seminar on management principles CGSA is the first eco-efficient port in Ecuador MICTSI celebrates 10th year 07 Latin American navy training ships arrive in Guayaquil 10 Thousands join 3rd Carrera Contecon BGT earning confidence of oil, gas sectors 11 Run enables CMSA to donate eyeglasses to school children 08 BGT celebrates Chairman’s Cup nod CMSA football club reaches league finals in maiden season Shaping BGT’s work culture for exceptional customer experience ICTSI Foundation donates classrooms in Manamoc Island, Saranggani, Misamis Oriental GLOBAL OPERATIONS is published by the Public Relations Office of International Container Terminal Services, Inc. for the employees, shareholders, clients and friends of the ICTSI Group. Narlene A. Soriano Jupiter L. -

Port Development and Productivity Improvement

Chapter 2. Status and Challenges on Sustainable Port Development and Productivity Improvement 2.1 Port Development and Productivity: current situation Current chapter offers “as is” analysis of the port development and productivity in selected UNESCAP member States. For each included country, it offers a) a general overview, b) national port development policies, c) examples of national good practices and d) challenges for further port development and productivity enhancement. 2.1.1 Bangladesh 1) Overview Bangladesh is the 42nd largest market-based economy in nominal term in the world and 31st largest by purchasing power parity. It is classified among the next eleven emerging market middle income economies and is considered to be a frontier market. Over the past few years, Bangladeshi economy has been growing rapidly and it continues to grow at an impressive rate. According to the IMF, Bangladesh remained the second fastest growing major economy from 2016 to 2018, with a rate of 7.0 percent. Figure 2.1.1.a. Bangladesh GDP per capita, PPP, current international $ price, 1980-2024 (Projected) 8,000 70,000 GDPper capita,PPP(current international $ 7,000 60,000 6,000 50,000 5,000 40,000 4,000 30,000 prices) 3,000 20,000 prices) 2,000 1,000 10,000 0 0 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2012 2015 2019 2020 2024 Asia and Pacific GDPper capita,PPP(current international $ Advanced economies Emerging market and developing economies Bangladesh Source: IMF Data Mapper, accessed on April 2019. Footnote: GDP per capita, PPP, current international $: in this report, we adopted GDP per capita, PPP, current international dollar as an economic measurement from IMF to make 3 comparative balance among the 11 selected countries, in order to measure purchasing power parity (PPP) rate of GDP per capita, which based on international dollar. -

Preparatory Survey on Promotion of TOD for Urban Railway in the Republic of the Philippines Final Report Final Report

the Republic of Philippines Preparatory Survey on Promotion of TOD for Urban Railway in Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC) Philippine National Railways (PNR) Preparatory Survey on Promotion of TOD for Urban Railway in the Republic of the Philippines Final Report Final Report March 2015 March 2015 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) ALMEC Corporation Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. 1R CR(3) 15-011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MAIN TEXT 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background and Rationale of the Study ....................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Objectives, Study Area and Counterpart Agencies ...................................................... 1-3 1.3 Study Implementation ................................................................................................... 1-4 2 CONCEPT OF TOD AND INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT ......................................... 2-1 2.1 Consept and Objectives of TOD ................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Approach to Implementation of TOD for NSCR ............................................................ 2-2 2.3 Good Practices of TOD ................................................................................................. 2-7 2.4 Regional Characteristics and Issues of the Project Area ............................................. 2-13 2.5 Corridor Characteristics and -

(Microsoft Powerpoint

Workshop 2010 of the Asian Network for Prevention of Illegal Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Waste Border Control Activities and Challenges for Tackling Illegal Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes January 27 – 29, 2010 Yokohama, Japan Outline of the Presentation 1. Bureau of Customs a. Five-Year Strategic Plan (2008-2012) b. Vision and Mission c. Strategic Goals d. Territorial Jurisdiction Collection Districts e. Electronic to Mobile Import Assessment (E2M IAS) 2. Environmental Protection Unit (EPU) Enforcement and Security Service (ESS) a. Creation b. Duties and Functions c. Personnel Complement d. Coverage e. Authority Outline of the Presentation 3. Enhancement Programs with Partner Agencies a. Megaports Initiative Project b. X-ray Inspection Project c. Philippine Customs Intelligence System (PCIS) d. Coast Watch South (CWS) e. Inter-Agency Technical Working Group on Border Crossing f. Philippine Border Management Project (PBMP) g. Nationwide Port Operations and Law Enforcement Organizational Network for a Strong Republic (The Network) h. Strategic Partnership on Immigration, Customs, Quarantine Enforcement (SPICQE) BUREAU OF CUSTOMS FIVE - YEAR STRATEGIC PLAN 2008 -2012 ISO 9001:2008 (Quality Management System) ISO 27001:2005 (Information Security Management System ““A customs administration which is among the world’s best that every Filipino can be proud of. ““ To enhance revenue collection; To provide quality service to stakeholders with professionalism and integrity; To facilitate trade in a secured manner; To effectively curb smuggling; To be compliant to international best practices and standards. Strategic Goals 1) ENHANCED REVENUE COLLECTION -Continuing top priority 2) DEVELOPED PERSONNEL COMPETENCE AND WELFARE -Organization is only as good as the people who comprise it. -

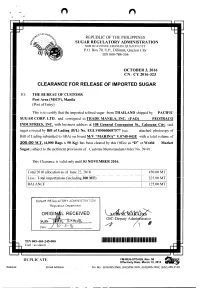

ORIGI L RECEIVED WNW .F,401Ts CLEARANCE for RELEASE OF

, , O-F A G '0 041 ,4 .,.‘4'_ & REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES a.gr - c- a1.0 .... SUGAR REGULATORY ADMINISTRATION NORTH AVENUE. DILIMAN, QUEZON CITY P.O. Box 70. U.P., Diliman, Quezon City TIN 000-784-336 OCTOBER 3, 2016 CN : CY 2016-323 CLEARANCE FOR RELEASE OF IMPORTED SUGAR THE BUREAU OF CUSTOMS Port Area (MICP), Manila (Port of Entry) This is to certify that the imported refined sugar from THAILAND shipped by PACIFIC SUGAR CORP. LTD. and consigned to TRADE MANILA, INC. (FAO) PEOTRACO INDUSTRIES, INC. with business address at 108 General Concepcion St., Caloocan City, said sugar covered by Bill of Lading (B/L) No. EGLV050600687577 (see attached photocopy of Bill of Lading submitted to SRA) on board MN "MARINA" V.0740-043E with a total volume of 200.00 M.T. (4,000 Bags x 50 Kg) has been cleared by this Office as "D" or World Market Sugar, subject to the pertinent provisions of Customs Memorandum Order No. 39-91. This Clearance is valid only until 03 NOVEMBER 2016. Total 2016 allocation as of June 22, 2016 450.00 MT Less : Total importations (including 200 MT) 325.00 MT BALANCE 125.00 MT SUGAR REGULATORY ADMINISTRATION Regulation Department ORIGI L RECEIVED 01C-Deputy Admi strator WNW .F,401ts Date - 3 - TIN 005-469-245-000 111111111 41111111111111111111111111111111111 Encl : as stated DL-PLICATE FM-REG-STD-026, Rev. 00 Effectivity Date: March 12, 2015 Website: • , Email Address: Tel. No.: (632)455-2566, (632)455-3376, (632)455-7402, (632) 455-2135 • foN REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES SUGAR REGULATORY ADMINISTRATION NORTH AVENUE, DILIMAN. -

12120648 01.Pdf

The Master Plan and Feasibility Study on the Establishment of an ASEAN RO-RO Shipping Network and Short Sea Shipping FINAL REPORT: Volume 1 Exchange rates used in the report US$ 1.00 = JPY 81.48 EURO 1.00 = JPY 106.9 = US$ 1.3120 BN$ 1.00 = JPY 64.05 = US$ 0.7861 IDR 1.00 = JPY 0.008889 = US$ 0.0001091 MR 1.00 = JPY 26.55 = US$ 0.3258 PhP 1.00 = JPY 1.910 = US$ 0.02344 THB 1.00 = JPY 2.630 = US$ 0.03228 (as of 20 April, 2012) The Master Plan and Feasibility Study on the Establishment of an ASEAN RO-RO Shipping Network and Short Sea Shipping FINAL REPORT: Volume 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 – Literature Review and Field Surveys Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................... vii List of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... xii Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................................ xvii 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.1 Scope of the Study ................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 Overall -

PORT of MANILA - Bls with No Entries As of June 4, 2021 Actual Cargo Arrival Date of June 3, 2021

PORT OF MANILA - BLs with No Entries as of June 4, 2021 Actual Cargo Arrival Date of June 3, 2021 ACTUAL DATE ACTUAL DATE OF No. CONSIGNEE/NOTIFY PARTY CONSIGNEE ADDRESS REGNUM BL DESCRIPTION OF ARRIVAL DISCHARGED 220 H ESQUERRA ST. BALATONG INDUSTRIAL AND BALATONG B. PULILAN AGRICULTURAL ENGINES HS:840790 AG 1 6/3/2021 6/3/2021 MSK0020-21 293177772 MFG CORP BULACAN 3005 JUN RICULTURAL WATER PUMPS HS:841370 NATIVIDAD 09175203958 NINO VILLA DE LIPA 2 BOLIMA TRADING BLK1 LOT7 SABANG LIPA CITY 2 6/3/2021 6/3/2021 MSK0020-21 292907947 SOLAR PANEL HS CODE 8541.40 AND 8 STO BATANGAS PHILIPPINES. MANILA SOUTH PORT LIBYA ST. GREEN HEIGHTS C E V CONSUMER GOODS 3 SUBD NANGKA MARIKINA 6/3/2021 6/3/2021 MSK0020-21 293177818 VINYL PLANK HS CODE:391810 TRADING 25 1808 PHILIPPINES 1202 DASMA CORPORATE CENTER 321 DASMARINAS PARTS OF FREEZER HS CODE: 8418.99 CAMEL APPLIANCES MFG 4 ST. BINONDO MANILA 6/3/2021 6/3/2021 MSK0020-21 293403710 COMPRESSOR HS CODE: 8418.30 FA X: 86- CORP RM PHILIPPINES FAX 22-88261806 006322410718 1202 DASMA CORPORATE CENTER 321 DASMARINAS CAMEL APPLIANCES MFG PARTS OF FAN HS CODE:8414.90 FAX : 86- 5 ST. BINONDO MANILA 6/3/2021 6/3/2021 MSK0020-21 293403672 CORP RM 22-88261806 PHILIPPINES FAX 006322410718 R404A AKASHIFRON REFRIGERANT PAC CUPANG MUNTINLUPA KING: N.W.:10.9KG/CYL TOTAL NET W DELSA INC KM 24 EAST 6 CITY 1771 PHILLIPINES TEL 6/3/2021 6/3/2021 MSK0020-21 293177743 EIGHT:9156KGS TOTAL GROSS WEIGHT:1 SERVICE RD BO 850 2964 2096KGS DISPOSABLE CANS CLASS:2.2 ;UN NO.:3337 H.S.