Cargo Truck Ban: Bad Timing, Faulty Analysis, Policy Failure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macrofouler Community Succession in South Harbor, Manila Bay, Luzon Island, Philippines During the Northeast Monsoon Season of 2017–2018

Philippine Journal of Science 148 (3): 441-456, September 2019 ISSN 0031 - 7683 Date Received: 26 Mar 2019 Macrofouler Community Succession in South Harbor, Manila Bay, Luzon Island, Philippines during the Northeast Monsoon Season of 2017–2018 Claire B. Trinidad1, Rafael Lorenzo G. Valenzuela1, Melody Anne B. Ocampo1, and Benjamin M. Vallejo, Jr.2,3* 1Department of Biology, College of Arts and Sciences, University of the Philippines Manila, Padre Faura Street, Ermita, Manila 1000 Philippines 2Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology, College of Science, University of the Philippines Diliman, Diliman, Quezon City 1101 Philippines 3Science and Society Program, College of Science, University of the Philippines Diliman, Diliman, Quezon City 1101 Philippines Manila Bay is one of the most important bodies of water in the Philippines. Within it is the Port of Manila South Harbor, which receives international vessels that could carry non-indigenous macrofouling species. This study describes the species composition of the macrofouling community in South Harbor, Manila Bay during the northeast monsoon season. Nine fouler collectors designed by the North Pacific Marine Sciences Organization (PICES) were submerged in each of five sampling points in Manila Bay on 06 Oct 2017. Three collection plates from each of the five sites were retrieved every four weeks until 06 Feb 2018. Identification was done via morphological and CO1 gene analysis. A total of 18,830 organisms were classified into 17 families. For the first two months, Amphibalanus amphitrite was the most abundant taxon; in succeeding months, polychaetes became the most abundant. This shift in abundance was attributed to intraspecific competition within barnacles and the recruitment of polychaetes. -

Part Ii Metro Manila and Its 200Km Radius Sphere

PART II METRO MANILA AND ITS 200KM RADIUS SPHERE CHAPTER 7 GENERAL PROFILE OF THE STUDY AREA CHAPTER 7 GENERAL PROFILE OF THE STUDY AREA 7.1 PHYSICAL PROFILE The area defined by a sphere of 200 km radius from Metro Manila is bordered on the northern part by portions of Region I and II, and for its greater part, by Region III. Region III, also known as the reconfigured Central Luzon Region due to the inclusion of the province of Aurora, has the largest contiguous lowland area in the country. Its total land area of 1.8 million hectares is 6.1 percent of the total land area in the country. Of all the regions in the country, it is closest to Metro Manila. The southern part of the sphere is bound by the provinces of Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal, and Quezon, all of which comprise Region IV-A, also known as CALABARZON. 7.1.1 Geomorphological Units The prevailing landforms in Central Luzon can be described as a large basin surrounded by mountain ranges on three sides. On its northern boundary, the Caraballo and Sierra Madre mountain ranges separate it from the provinces of Pangasinan and Nueva Vizcaya. In the eastern section, the Sierra Madre mountain range traverses the length of Aurora, Nueva Ecija and Bulacan. The Zambales mountains separates the central plains from the urban areas of Zambales at the western side. The region’s major drainage networks discharge to Lingayen Gulf in the northwest, Manila Bay in the south, the Pacific Ocean in the east, and the China Sea in the west. -

Additional Modified Routes Allowed for the Operation of Traditional

Republic of the Philippircs Department of Transportation LAND TRANSPORTATION FRANCHISING & REGULATORY BOARI) East Avenue, Quezon City MEMORANDUM CIRCULAR NO.2020 - 013 SUBJECT ADDITIONAL MODIFIED ROUTES ALLOWED FOR THE OPERATION OF TR,{DITIONAL PUJ VEHICLES DURING THE PERIOD OF GCQ IN METRO MANILA WHEREAS, pursuant to the guidelines of the Department of Transportation (DOTr) for a calibrated and gradual opening of public transportation in Metro Manila and those in nearby provinces, the Board has since then made the necessary monitoring on the daily operations of thl initial routes allowed to operate; WHEREAS, under Item II.b. of MC 2020-O26,the Board may issue additional routes to resume operations based on passenger demand; WHEREAS, based on the monitoring and coordination with local government urits in Metro Manila, there is a continuous need to open additional routes for kaditional PUJs to sorye passenger demand; NOW TIIEREF0RE, for and in consideration of the foregoing the Board" hereby allows the additional routes (attached as ANNEX "A") for traditional PUJs to operate within Metro Manila and entering Metro Manila starting NOVEMBER 18, 2020 or u. *uy be allowed by the Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (rATF-EIF) This Circular shall cover grantees of valid and existing Certificate of Public Convenience (CpC) for Public Utility Jeepneys (PUJ) or that Application for Extension of Validity of CpC has been filed for expired CPCs operating in the National Capital Region. Operators with expired CpC covered by the provisions of Board Resolution No. 062 Series of 202A dated 29 Aprii 2A20 and, Board Resolution No. 100 dated 09 May 2a20 arc tikswise coversd. -

JEEP Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

JEEP bus time schedule & line map JEEP Lagro Panay welcome View In Website Mode The JEEP bus line Lagro Panay welcome has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bristol Street / Bronson Street Intersection, Quezon City →Quezon Avenue / D Tuazon Intersection West Bound, Quezon City: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest JEEP bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next JEEP bus arriving. Direction: Bristol Street / Bronson Street JEEP bus Time Schedule Intersection, Quezon City →Quezon Avenue / D Bristol Street / Bronson Street Intersection, Quezon Tuazon Intersection West Bound, Quezon City City →Quezon Avenue / D Tuazon Intersection West 67 stops Bound, Quezon City Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Bristol Street / Bronson Street Intersection, Quezon City Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Bristol Street, Quezon City Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Bristol, Philippines Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Regalado Highway, Quezon City Friday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Regalado Highway, Quezon City Saturday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Regalado Highway, Quezon City Regalado Highway, Quezon City JEEP bus Info Regalado Highway / Burbank Intersection Direction: Bristol Street / Bronson Street Quezon City Intersection, Quezon City →Quezon Avenue / D Tuazon Intersection West Bound, Quezon City Stops: 67 Regalado Highway, Quezon City Trip Duration: 99 min Line Summary: Bristol Street / Bronson Street Regalado Highway / Commonwealth Avenue Intersection, Quezon City, Bristol -

JEEP Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

JEEP bus time schedule & line map JEEP General Avenue / Gsisea Street Intersection, View In Website Mode Quezon City →Quezon Blvd, Manila The JEEP bus line (General Avenue / Gsisea Street Intersection, Quezon City →Quezon Blvd, Manila) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) General Avenue / Gsisea Street Intersection, Quezon City →Quezon Blvd, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM (2) Quezon Blvd, Manila →General Avenue / Gsisea Street Intersection, Quezon City: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest JEEP bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next JEEP bus arriving. Direction: General Avenue / Gsisea Street JEEP bus Time Schedule Intersection, Quezon City →Quezon Blvd, Manila General Avenue / Gsisea Street Intersection, Quezon 59 stops City →Quezon Blvd, Manila Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM General Avenue / Gsisea Street Intersection, Quezon City Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Soriano, Philippines Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM General Avenue / Molave Intersection, Quezon City Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM General Avenue, Philippines Friday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM General Avenue / Assistant Branchesntersection, Saturday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Quezon City Auditing, Philippines Engineering / Legal Intersection, Quezon City Legal, Philippines JEEP bus Info Direction: General Avenue / Gsisea Street St Mary / Benƒts, Quezon City Intersection, Quezon City →Quezon Blvd, Manila Stops: 59 Beneƒts / Gsis Avenue, Quezon City Trip Duration: 63 min Line Summary: -

ICTSI Opens Its PNG Terminals CGSA Strengthens Market Position PM O’Neill Special Guest at Motukea Rites Gets Gov’T Approval to Handle Mega Vessels

Vol. 28, Issue N.º 07 July 2018 The Official Publication of International Container Terminal Services, Inc. .com ictsi www. ICTSI opens its PNG terminals CGSA strengthens market position PM O’Neill special guest at Motukea rites gets gov’t approval to handle mega vessels International Container Terminal Services, Inc. (ICTSI) has International Container Terminal Services, Inc.’s (ICTSI) largest opened its terminals in Papua New Guinea–Motukea International port concession in the Americas, Contecon Guayaquil SA (CGSA), further strengthened its market position as the main trading gateway Terminal (MIT) in the capital Port Moresby and Lae Tidal Basin in the entire Ecuador after recently getting the government’s nod to in Morobe Province–bringing ICTSI’s portfolio to 30 ports. service larger vessels. GLOBAL OPERATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 04 ICTSI opens its PNG terminals 09 YICTL names new officers 06 CGSA strengthens market position PICT holds seminar on management principles CGSA is the first eco-efficient port in Ecuador MICTSI celebrates 10th year 07 Latin American navy training ships arrive in Guayaquil 10 Thousands join 3rd Carrera Contecon BGT earning confidence of oil, gas sectors 11 Run enables CMSA to donate eyeglasses to school children 08 BGT celebrates Chairman’s Cup nod CMSA football club reaches league finals in maiden season Shaping BGT’s work culture for exceptional customer experience ICTSI Foundation donates classrooms in Manamoc Island, Saranggani, Misamis Oriental GLOBAL OPERATIONS is published by the Public Relations Office of International Container Terminal Services, Inc. for the employees, shareholders, clients and friends of the ICTSI Group. Narlene A. Soriano Jupiter L. -

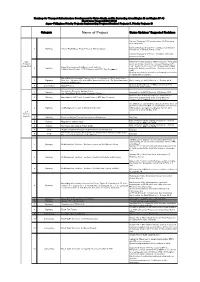

Name of Project Status Updates/ Suggested Revisions

Roadmap for Transport Infrustructure Development for Metro Manila and Its Surrunding Areas(Region III and Region IV-A) Short-term Program(2014-2016) Japan-Philippines Priority Projects: Implementing Progress(Comitted Projects 5, Priority Projects 8) Category Name of Project Status Updates/ Suggested Revisions Contract Packages I & II covering about 14.65 km have been completed. Contract Package III (2.22 km + 2 bridges): Construction 1 Highways Arterial Road Bypass Project Phase II, Plaridel Bypass Progress as of 25 April 2015 is 13.02%. Contract Package IV (7.74 km + 2 bridges): Still under procurement stage. ODA Notice to Proceed Issued to CMX Consortium. The project Projects is not specifically cited in the Transport Roadmap. LRT (Committed) Line 1 South Ext and Line 2 East Ext were cited instead, Capacity Enhancement of Mass Transit Systems 2 Railways separately. Updates on LRT Line 1 South Extension and in Metro Manila Project (LRT1 Extension and LRT 2 East Extentsion) O&M: Ongoing pre-operation activities; and ongoing procurement of independent consultant. Metro Manila Interchanges Construction VI - 2 packages d. EDSA/ North Ave. - 3 Highways West Ave.- Mindanao Ave. and EDSA/ Roosevelt Ave. and f. C5: Green Meadows/ Confirmed by the NEDA Board on 17 October 2014 Acropolis/CalleIndustria Ongoing. Detailed Design is 100% accomplished. Final 4 Expressways CLLEX Phase I design plans under review. North South Commuter Railway Project 1 Railways Approved by the NEDA Board on 16 February 2015 (ex- Mega Manila North-South Commuter Railway) New Item, Line 2 West Extension not included in the 2 Railways Metro Manila CBD Transit System Project (LRT2 West Extension) short-term program (until 2016). -

FY 2009 (Annual)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY METROPOLITAN MANILA DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY CY 2009 ANNUAL ACCOMPLISHMENT REPORT Metro Gwapo, MMDA’s flagship program, has come a long way since its inception a couple of years ago. Given the glaring blight in many areas of the Metropolis, it is a pleasant surprise to see that a substantial physical change for the better has come upon Metro Manila. Inch by painful inch, Metro Manila is slowly turning into a livable and healthy city as envisioned by the leaders of this prime metropolis, both past and present. Though much remains to be done, we have taken the baby steps. With the expert use of the principle utilizing outer change to bring about inner change, MMDA has embarked on the process of social engineering. Undeniably the opposite process of starting from within to realize outer change is faster but, owing to the psychological immaturity of most of our countrymen, the principle of the outer to the inner is deemed more suitable. Here, the use of visuals help impart the lessons to a largely unthinking public. Among the more important projects for CY 2009 are the following: SOCIAL SERVICES PGMA Workers’ Inn (aka) Gwapotel Meant to ease the difficulties of the workers whose homes are far from the Metropolis, the Gwapotel or Workers Inn serves as a temporary sleeping and bathing quarters for a variety of clients (i.e. government employees, laborers, security guards, vendors, seamen and seminar / convention participants, among others. As of 2009, the MMDA operated two such inns, one in Port Area and another in Abad Santos Tondo, Manila. -

Preparatory Survey on Promotion of TOD for Urban Railway in the Republic of the Philippines Final Report Final Report

the Republic of Philippines Preparatory Survey on Promotion of TOD for Urban Railway in Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC) Philippine National Railways (PNR) Preparatory Survey on Promotion of TOD for Urban Railway in the Republic of the Philippines Final Report Final Report March 2015 March 2015 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) ALMEC Corporation Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. 1R CR(3) 15-011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MAIN TEXT 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background and Rationale of the Study ....................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Objectives, Study Area and Counterpart Agencies ...................................................... 1-3 1.3 Study Implementation ................................................................................................... 1-4 2 CONCEPT OF TOD AND INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT ......................................... 2-1 2.1 Consept and Objectives of TOD ................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Approach to Implementation of TOD for NSCR ............................................................ 2-2 2.3 Good Practices of TOD ................................................................................................. 2-7 2.4 Regional Characteristics and Issues of the Project Area ............................................. 2-13 2.5 Corridor Characteristics and -

Battling Congestion in Manila: the Edsa Problem

Transport and Communications Bulletin for Asia and the Pacific No. 82, 2013 BATTLING CONGESTION IN MANILA: THE EDSA PROBLEM Yves Boquet ABSTRACT The urban density of Manila, the capital of the Philippines, is one the highest of the world and the rate of motorization far exceeds the street capacity to handle traffic. The setting of the city between Manila Bay to the West and Laguna de Bay to the South limits the opportunities to spread traffic from the south on many axes of circulation. Built in the 1940’s, the circumferential highway EDSA, named after historian Epifanio de los Santos, seems permanently clogged by traffic, even if the newer C-5 beltway tries to provide some relief. Among the causes of EDSA perennial difficulties, one of the major factors is the concentration of major shopping malls and business districts alongside its course. A second major problem is the high number of bus terminals, particularly in the Cubao area, which provide interregional service from the capital area but add to the volume of traffic. While authorities have banned jeepneys and trisikel from using most of EDSA, this has meant that there is a concentration of these vehicles on side streets, blocking the smooth exit of cars. The current paper explores some of the policy options which may be considered to tackle congestion on EDSA . INTRODUCTION Manila1 is one of the Asian megacities suffering from the many ills of excessive street traffic. In the last three decades, these cities have experienced an extraordinary increase in the number of vehicles plying their streets, while at the same time they have sprawled into adjacent areas forming vast megalopolises, with their skyline pushed upwards with the construction of many high-rises. -

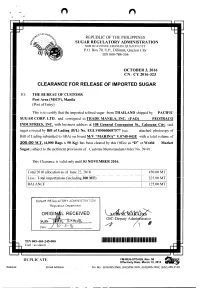

ORIGI L RECEIVED WNW .F,401Ts CLEARANCE for RELEASE OF

, , O-F A G '0 041 ,4 .,.‘4'_ & REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES a.gr - c- a1.0 .... SUGAR REGULATORY ADMINISTRATION NORTH AVENUE. DILIMAN, QUEZON CITY P.O. Box 70. U.P., Diliman, Quezon City TIN 000-784-336 OCTOBER 3, 2016 CN : CY 2016-323 CLEARANCE FOR RELEASE OF IMPORTED SUGAR THE BUREAU OF CUSTOMS Port Area (MICP), Manila (Port of Entry) This is to certify that the imported refined sugar from THAILAND shipped by PACIFIC SUGAR CORP. LTD. and consigned to TRADE MANILA, INC. (FAO) PEOTRACO INDUSTRIES, INC. with business address at 108 General Concepcion St., Caloocan City, said sugar covered by Bill of Lading (B/L) No. EGLV050600687577 (see attached photocopy of Bill of Lading submitted to SRA) on board MN "MARINA" V.0740-043E with a total volume of 200.00 M.T. (4,000 Bags x 50 Kg) has been cleared by this Office as "D" or World Market Sugar, subject to the pertinent provisions of Customs Memorandum Order No. 39-91. This Clearance is valid only until 03 NOVEMBER 2016. Total 2016 allocation as of June 22, 2016 450.00 MT Less : Total importations (including 200 MT) 325.00 MT BALANCE 125.00 MT SUGAR REGULATORY ADMINISTRATION Regulation Department ORIGI L RECEIVED 01C-Deputy Admi strator WNW .F,401ts Date - 3 - TIN 005-469-245-000 111111111 41111111111111111111111111111111111 Encl : as stated DL-PLICATE FM-REG-STD-026, Rev. 00 Effectivity Date: March 12, 2015 Website: • , Email Address: Tel. No.: (632)455-2566, (632)455-3376, (632)455-7402, (632) 455-2135 • foN REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES SUGAR REGULATORY ADMINISTRATION NORTH AVENUE, DILIMAN. -

PORT of MANILA - Bls with No Entries As of June 4, 2021 Actual Cargo Arrival Date of June 3, 2021

PORT OF MANILA - BLs with No Entries as of June 4, 2021 Actual Cargo Arrival Date of June 3, 2021 ACTUAL DATE ACTUAL DATE OF No. CONSIGNEE/NOTIFY PARTY CONSIGNEE ADDRESS REGNUM BL DESCRIPTION OF ARRIVAL DISCHARGED 220 H ESQUERRA ST. BALATONG INDUSTRIAL AND BALATONG B. PULILAN AGRICULTURAL ENGINES HS:840790 AG 1 6/3/2021 6/3/2021 MSK0020-21 293177772 MFG CORP BULACAN 3005 JUN RICULTURAL WATER PUMPS HS:841370 NATIVIDAD 09175203958 NINO VILLA DE LIPA 2 BOLIMA TRADING BLK1 LOT7 SABANG LIPA CITY 2 6/3/2021 6/3/2021 MSK0020-21 292907947 SOLAR PANEL HS CODE 8541.40 AND 8 STO BATANGAS PHILIPPINES. MANILA SOUTH PORT LIBYA ST. GREEN HEIGHTS C E V CONSUMER GOODS 3 SUBD NANGKA MARIKINA 6/3/2021 6/3/2021 MSK0020-21 293177818 VINYL PLANK HS CODE:391810 TRADING 25 1808 PHILIPPINES 1202 DASMA CORPORATE CENTER 321 DASMARINAS PARTS OF FREEZER HS CODE: 8418.99 CAMEL APPLIANCES MFG 4 ST. BINONDO MANILA 6/3/2021 6/3/2021 MSK0020-21 293403710 COMPRESSOR HS CODE: 8418.30 FA X: 86- CORP RM PHILIPPINES FAX 22-88261806 006322410718 1202 DASMA CORPORATE CENTER 321 DASMARINAS CAMEL APPLIANCES MFG PARTS OF FAN HS CODE:8414.90 FAX : 86- 5 ST. BINONDO MANILA 6/3/2021 6/3/2021 MSK0020-21 293403672 CORP RM 22-88261806 PHILIPPINES FAX 006322410718 R404A AKASHIFRON REFRIGERANT PAC CUPANG MUNTINLUPA KING: N.W.:10.9KG/CYL TOTAL NET W DELSA INC KM 24 EAST 6 CITY 1771 PHILLIPINES TEL 6/3/2021 6/3/2021 MSK0020-21 293177743 EIGHT:9156KGS TOTAL GROSS WEIGHT:1 SERVICE RD BO 850 2964 2096KGS DISPOSABLE CANS CLASS:2.2 ;UN NO.:3337 H.S.