Vol. 51, No. 4 (December 2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CC News DEC 14 IL

December 2014 When the time came for the purification rites required by the Law of Moses, Joseph and Mary took him to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord (as it is written in the Law of the Lord, “Every firstborn male is to be consecrated to the Lord”), and to offer a sacrifice in keeping with what is said in the Law of the Lord: “a pair of doves or two young pigeons.” (Luke 2:22–24) At this time of year, the religious Christian community celebrates the birth of Jesus, the Messiah. My family and I have always participated in these celebrations, though as Jewish believers in Jesus, we’ve adopted a more restrained level of holiday cultural activity (decorating, shopping, party-attending) than many around us. We’ve also always observed Chanukah, which begins this year on the evening of Tuesday, December 16, and concludes eight days later at sundown on December 24. Though Chanukah, also known as the Feast of Dedication or Festival of Lights, is a minor feast in the yearly Jewish ritual cycle, our family always lit the candles in our menorah. As we did, we revisited the exciting account of the Maccabean victory over Antiochus IV Epiphanes in 164 BC, and thanked God for the story of the cleansed, rededicated temple and the sacred oil lamp that burned for eight miraculous days when it only had enough oil for a single day. In the spiritual darkness of those days, seeing the light burn once again in the holy place after years of darkness and idol worship must have been pure joy for the Maccabees. -

Ref. # Lang. Section Title Author Date Loaned Keywords 6437 Cg Kristen Liv En Bro Til Alle Folk Dahl, Øyvind 1981

Lang. Section Title Author Date Loaned Keywords Ref. # 6437 cg Kristen liv En bro til alle folk Dahl, Øyvind 1981 ><'14/11/19 D Dansk Mens England sov Churchill, Winston S. 1939 Arms and the 3725 Covenant D Dansk Gourmet fra hummer a la carte til æg med Lademann, Rigor Bagger 1978 om god vin og 4475 kaviar (oversat og bearbejdet af) festlig mad 7059 E Art Swedish Silver Andrén, Erik 1950 5221 E Art Norwegian Painting: A Survey Askeland, Jan 1971 ><'06/10/21 E Art Utvald att leva Asker, Randi 1976 7289 11211 E Art Rose-painting in Norway Asker, Randi 1965 9033 E Art Fragments The Art of LLoyd Herfindahl Aurora University 1994 E Art Carl Michael Bellman, The life and songs of Austin, Britten 1967 9318 6698 E Art Stave Church Paintings Blindheim, Martin 1965 7749 E Art Folk dances of Scand Duggan, Anne Schley et al 1948 9293 E Art Art in Sweden Engblom, Sören 1999 contemporary E Art Treasures of early Sweden Gidlunds Statens historiska klenoder ur 9281 museum äldre svensk historia 5964 E Art Another light Granath, Olle 1982 9468 E Art Joe Hills Sånger Kokk, Enn (redaktør) 1980 7290 E Art Carl Larsson's Home Larsson, Carl 1978 >'04/09/24 E Art Norwegian Rosemaling Miller, Margaret M. and 1974 >'07/12/18 7363 Sigmund Aarseth E Art Ancient Norwegian Design Museum of National 1961 ><'14/04/19 10658 Antiquities, Oslo E Art Norwegian folk art Nelson, Marion, Editor 1995 the migration of 9822 a tradition E Art Döderhultarn Qvist, Sif 1981? ><'15/07/15 9317 10181 E Art The Norwegian crown regalia risåsen, Geir Thomas 2006 9823 E Art Edvard Munck - Landscapes of the mind Sohlberg, Harald 1995 7060 E Art Swedish Glass Steenberg, Elisa 1950 E Art Folk Arts of Norway Stewart, Janice S. -

From Tel Aviv to Nazareth: Why Jews Become Messianic Jews

JETS 48/4 (December 2005) 771-800 FROM TEL AVIV TO NAZARETH: WHY JEWS BECOME MESSIANIC JEWS SCOT MCKNIGHT WITH R. BOAZ JOHNSON* I. INTRODUCTION Plotting conversion stories is my sacred hobby. Lauren Winner's best-selling memoir of her conversion from Reform Judaism to Orthodox Judaism and then on to evangelical Christianity is one of the best reads of the last decade, and her story illustrates one type of conversion by Jews to the Christian faith. Her aesthetically-prompted and liturgically-shaped conversion story is as difficult to plot as it is joyous to read—she tells us about things that do not matter to conversion theory while she does not tell us about things that do matter. In her defense, she did not write her story so the theoretically-inclined could analyze her con- version. Here is a defining moment in her conversion story:1 My favorite spot at The Cloisters was a room downstairs called the Treasury. In glass cases were small fragile reliquaries and icons and prayer books. In one case was a tiny psalter and Book of Hours. It lay open to a picture of Christ's arrest. I could barely read the Latin. Sometimes I would stand in front of that psalter for an hour. I wanted to hold it in my hand. My boyfriend in college was Dov, an Orthodox Jew from Westchester County whom I had met through Rabbi M. Dov thought all this [her studying American Christianity and interest in things Christian] was weird. He watched me watch the Book of Hours, and he watched me write endless papers about religious re- vivals in the South. -

Charles Porterfield Krauth: the American Chemnitz

The 37th Annual Reformation Lectures Reformation Legacy on American Soil Bethany Lutheran College S. C. Ylvisaker Fine Arts Center Mankato, Minnesota October 28-29, 2004 Lecture Number Three: Charles Porterfield Krauth: The American Chemnitz The Rev. Prof. David Jay Webber Ternopil’, Ukraine Introduction C. F. W. Walther, the great nineteenth-century German-American churchman, has some- times been dubbed by his admirers “the American Luther.”1 While all comparisons of this nature have their limitations, there is a lot of truth in this appellation. Walther’s temperament, his lead- ership qualities, and especially his theological convictions would lend legitimacy to such a de- scription. Similarly, we would like to suggest that Charles Porterfield Krauth, in light of the unique gifts and abilities with which he was endowed, and in light of the thoroughness and balance of his mature theological work, can fittingly be styled “the American Chemnitz.” Krauth was in fact an avid student of the writings of the Second Martin, and he absorbed much from him in both form and substance. It is also quite apparent that the mature Krauth always attempted to follow a noticeably Chemnitzian, “Concordistic” approach in the fulfillment of his calling as a teacher of the church in nineteenth-century America. We will return to these thoughts in a little while. Be- fore that, though, we should spend some time in examining Krauth’s familial and ecclesiastical origins, and the historical context of his development as a confessor of God’s timeless truth. Krauth’s Origins In the words of Walther, Krauth was, without a doubt, the most eminent man in the English Lutheran Church of this country, a man of rare learning, at home no less in the old than in modern theology, and, what is of greatest import, whole-heartedly devoted to the pure doctrine of our Church, as he had learned to understand it, a noble man and without guile.2 But Krauth’s pathway to this kind of informed Confessionalism was not an easy one. -

Studia Patristica Vol

STUDIA PATRISTICA VOL. LXIII Papers presented at the Sixteenth International Conference on Patristic Studies held in Oxford 2011 Edited by MARKUS VINZENT Volume 11: Biblica Philosophica, Theologica, Ethica PEETERS LEUVEN – PARIS – WALPOLE, MA 2013 Table of Contents BIBLICA Mark W. ELLIOTT, St Andrews, UK Wisdom of Solomon, Canon and Authority ........................................ 3 Joseph VERHEYDEN, Leuven, Belgium A Puzzling Chapter in the Reception History of the Gospels: Victor of Antioch and his So-called ‘Commentary on Mark’ ...................... 17 Christopher A. BEELEY, New Haven, Conn., USA ‘Let This Cup Pass from Me’ (Matth. 26.39): The Soul of Christ in Origen, Gregory Nazianzen, and Maximus Confessor ...................... 29 Paul M. BLOWERS, Emmanuel Christian Seminary, Johnson City, Ten- nessee, USA The Groaning and Longing of Creation: Variant Patterns of Patristic Interpretation of Romans 8:19-23 ....................................................... 45 Riemer ROUKEMA, Zwolle, The Netherlands The Foolishness of the Message about the Cross (1Cor. 1:18-25): Embarrassment and Consent ............................................................... 55 Jennifer R. STRAWBRIDGE, Oxford, UK A Community of Interpretation: The Use of 1Corinthians 2:6-16 by Early Christians ................................................................................... 69 Pascale FARAGO-BERMON, Paris, France Surviving the Disaster: The Use of Psyche in 1Peter 3:20 ............... 81 Everett FERGUSON, Abilene, USA Some Patristic Interpretations -

On This Rock

On This Rock Twenty-Five Sermons & Addresses By Herman Amberg Preus Born in Kristiansand in southern Norway in 1825 Preus immigrated to America in 1851 upon acceptance of a Call to the Spring Prairie parish in southern Columbia County, Wisconsin. His entire ministry centered around the parish a short distance north of Madison, and, the Norwegian Synod. After the publication of Truth Unchanged, Unchanging by the Evangelical Lutheran Synod in 1979, which offered a sampling of the work of Ulrik Vilhelm Koren in English, work which I had headed up by invitation of former Bethany Lutheran College president B.W. Teigen, I began to work on material from the ministry of The Reverend President Herman Amberg Preus. He was first elected president at the 1862 Convention, succeeding Adolph Carl (A.C.) Preus [a cousin]. He had been president of the Norwegian Evangelical Lutheran Church in America from 1862 until his death in 1894, 32 years, one-half the life time of that church body. From the materials available to me the following has resulted. Because he was primarily a pastor, a preacher, I put these examples of his preaching first. To the best of my knowledge these are all the sermons and addresses of his that have ever been in my library, gathered from the Synod’s Maanedstidende (monthly) and Kirketidende (weekly periodical), from the Postil (book of sermons) it published, and from a booklet published in the parish in 1901 on the occasion of its 50th anniversary. The sermons are arranged here chronologically, beginning with Preus’ first sermon at Spring Prairie when he was a 26-year-old beginning his Ministry, to his last sermon before his death in 1894, when he was 69. -

December 1987

FOREWORD In this issue of the Quarterly the sermon by Pastor David Haeuser emphasizes that the proclamation of sin and grace must never be relegated to the back- ground, but must always be in the forefront of all of our church work. Rev. Haeuser is pastor of Christ Lutheran Church, Belle Gardens, California and also director of Project Christo Rey, a Hispanic mission in that area. The article by Pastor Herbert Larson on THE CENTEN- NIAL OF WALTHER'S DEATH is both interesting and timely. Pastor Larson shows from the history of the Norwegian Synod that there existed a warm and cordial relation- ship between Dr. Walther and the leaders of the Synod, and that we as a Synod are truly indebted to this man of God. Rev. Larson is pastor of Faith Lutheran Church, San Antonio, Texas. As the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) officially comes into existence on January 1, 1988, our readers will appreciate David Jay ~ebber'sresearch into the writings of some of the theologians of this new merger wherein he clearly shows that these teach- ings are un-Lutheran. David Webber was raised in the LCA and is presently a senior seminarian at Concordia Seminary, Fort Wayne, Indiana. An exegetical treatment of Romans 7: 14-25 by Professor Daniel Metzger explains the nature of the paradox in this section of Holy Scripture. Professor Metzger teaches religion and English at Bethany Lutheran College. He is currently on a sabbatical working on his doctorate. We also take this opportunity to wish our readers a blessed Epiphany and a truly happy and healthy New Year in the Name of the Christ-Child in whom alone we have lasting peace and joy. -

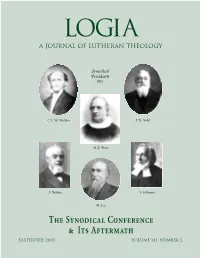

Logia 4/03 Text W/O

Logia a journal of lutheran theology Synodical Presidents C. F. W. Walther J. H. Sieker H. A. Preus J. Bading F. Erdmann M. Loy T S C I A eastertide 2003 volume xii, number 2 ei[ ti" lalei', wJ" lovgia Qeou' logia is a journal of Lutheran theology. As such it publishes articles on exegetical, historical, systematic, and liturgical theolo- T C A this issue shows the presidents of gy that promote the orthodox theology of the Evangelical the synods that formed the Evangelical Lutheran Lutheran Church. We cling to God’s divinely instituted marks of Synodical Conference (formed July at the church: the gospel, preached purely in all its articles, and the Milwaukee, Wisconsin). They include the sacraments, administered according to Christ’s institution. This Revs. C. F. W. Walther (Missouri), H. A. Preus name expresses what this journal wants to be. In Greek, LOGIA (Norwegian), J. H. Sieker (Minnesota), J. Bading functions either as an adjective meaning “eloquent,”“learned,” or (Wisconsin), M. Loy (Ohio), F. Erdmann (Illinois). “cultured,” or as a plural noun meaning “divine revelations,” “words,”or “messages.”The word is found in Peter :, Acts :, Pictures are from the collection of Concordia oJmologiva and Romans :. Its compound forms include (confes- Historical Institute, Rev. Mark A. Loest, assistant ajpologiva ajvnalogiva sion), (defense), and (right relationship). director. Each of these concepts and all of them together express the pur- pose and method of this journal. LOGIA considers itself a free con- ference in print and is committed to providing an independent L is indexed in the ATLA Religion Database, published by the theological forum normed by the prophetic and apostolic American Theological Library Association, Scriptures and the Lutheran Confessions. -

The Word-Of-God Conflict in the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod in the 20Th Century

Luther Seminary Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary Master of Theology Theses Student Theses Spring 2018 The Word-of-God Conflict in the utherL an Church Missouri Synod in the 20th Century Donn Wilson Luther Seminary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/mth_theses Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, Donn, "The Word-of-God Conflict in the utherL an Church Missouri Synod in the 20th Century" (2018). Master of Theology Theses. 10. https://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/mth_theses/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Theology Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE WORD-OF-GOD CONFLICT IN THE LUTHERAN CHURCH MISSOURI SYNOD IN THE 20TH CENTURY by DONN WILSON A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Luther Seminary In Partial Fulfillment, of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY THESIS ADVISER: DR. MARY JANE HAEMIG ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dr. Mary Jane Haemig has been very helpful in providing input on the writing of my thesis and posing critical questions. Several years ago, she guided my independent study of “Lutheran Orthodoxy 1580-1675,” which was my first introduction to this material. The two trips to Wittenberg over the January terms (2014 and 2016) and course on “Luther as Pastor” were very good introductions to Luther on-site. -

Lutheran Synod Quarterly

LUTHERAN SYNOD QUARTERLY VOLUME 52 • NUMBERS 2-3 JUNE–SEPTEMBER 2012 The theological journal of Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary LUTHERAN SYNOD QUARTERLY EDITOR-IN-CHIEF........................................................... Gaylin R. Schmeling BOOK REVIEW EDITOR ......................................................... Michael K. Smith LAYOUT EDITOR ................................................................. Daniel J. Hartwig PRINTER ......................................................... Books of the Way of the Lord FACULTY............. Adolph L. Harstad, Thomas A. Kuster, Dennis W. Marzolf, Gaylin R. Schmeling, Michael K. Smith, Erling T. Teigen The Lutheran Synod Quarterly (ISSN: 0360-9685) is edited by the faculty of Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary 6 Browns Court Mankato, Minnesota 56001 The Lutheran Synod Quarterly is a continuation of the Clergy Bulletin (1941–1960). The purpose of the Lutheran Synod Quarterly, as was the purpose of the Clergy Bulletin, is to provide a testimony of the theological position of the Evangelical Contents Lutheran Synod and also to promote the academic growth of her clergy roster by providing scholarly articles, rooted in the inerrancy of the Holy Scriptures and the LSQ Vol. 52, Nos. 2–3 (June–September 2012) Confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. ARTICLES AND SERMONS The Lutheran Synod Quarterly is published in March and December with a “God Has Gone Up With a Shout” - An Exegetical Study of combined June and September issue. Subscription rates are $25.00 U.S. per year -

A Cumulative Index to the Presbyterian Guardian, 1935-1979

A CUMULATIVE INDEX TO THE PRESBYTERIAN GUARDIAN, 1935-1979 Compiled by James T. Dennison, Jr. Copyright c 1985 Escondido, California TO MY BROTHER REV. CHARLES GILMORE DENNISON, B.D., M.A. BELOVED FELLOW SERVANT OF THE ESCHATOLOGICAL SERVANT HUSBAND, FATHER, PASTOR HISTORIAN OF THE ORTHODOX PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, 1982- FOND DISCIPLE OF J. GRESHAM MACHEN "...YOUR LIFE IS HID WITH CHRIST IN GOD"-- COL. 3:3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. PREFACE.................................................i 2. OUTLINE OF PUBLICATION DATA.............................ii 3. HOW TO USE THIS INDEX...................................v 4. AUTHOR/TITLE/SUBJECT, ETC. .............................1 5. BOOK REVIEWS............................................350 6. SCRIPTURE PASSAGES......................................364 7. PHOTOGRAPHS.............................................381 PREFACE The Presbyterian Guardian was established by Dr. J. Gresham Machen to serve as the voice of Presbyterian orthodoxy. Conceived in controversy, the first copy issued from the presses on October 7, 1935. Machen spearheaded the publication of the Guardian with the assistance of a group of ministers and laymen in the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA). The proximate cause of the Guardian was the disagreement between Machen and Dr. Samuel G. Craig, editor of Christianity Today (1930-1949). The nether cause was Machen's escalating struggle with modernism in the PCUSA. Machen had led in the formation of the Presbyterian Constitutional Covenant Union which was organized June 27, 1935 in Philadelphia. This group was committed to: (1) reform of the PCUSA; or (2) "failing that, to continue the true spiritual succession of that church in a body distinct from the existing organization." Dr. Craig had editorially questioned the wisdom of such a Union in the September 1935 issue of Christianity Today. -

Folk I Nord Møtte Prester Fra Sør Kirke- Og Skolehistorie, Minoritets- Og

KÅRE SVEBAK Folk i Nord møtte prester fra sør Kirke- og skolehistorie, minoritets- og språkpolitikk En kildesamling: 65 LIVHISTORIER c. 1850-1970 KSv side 2 INNHOLDSREGISTER: FORORD ......................................................................................................................................... 10 FORKORTELSER .............................................................................................................................. 11 SKOLELOVER OG INSTRUKSER........................................................................................................ 12 RAMMEPLAN FOR DÅPSOPPLÆRING I DEN NORSKE KIRKE ........................................................... 16 INNLEDNING .................................................................................................................................. 17 1. BERGE, OLE OLSEN: ................................................................................... 26 KVÆFJORD, BUKSNES, STRINDA ....................................................................................................... 26 BUKSNES 1878-88 .......................................................................................................................... 26 2. ARCTANDER, OVE GULDBERG: ................................................................... 30 RISØR, BUKSNES, SORTLAND, SOGNDAL, SIGDAL, MANDAL .................................................................. 30 RISØR 1879-81 ..............................................................................................................................