Why Is There No Church Unity Among Norwegian Lutherans in America?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Bergen Congregation Compiled for Golden Jubilee (51St Anniversary) July 12-13, 1936 by R

History of Bergen Congregation Compiled for Golden Jubilee (51st Anniversary) July 12-13, 1936 by R. S. Sigdestad The Bergen congregation in Day County, South Dakota, was organized in the home of Nels Williamson Sr., by Lynn Lake, in the autumn of 1885, by Rev. K. 0. Storli of Wilmot, S. Dak., on one of his mission journeys. It consisted of the following 17 voting members: Iver E. Skaare, Rasmus K. Mork, Ole Simonson, Ole E. Bakken, John J. Grove, Sakarias J. Sigdestad, Kolben T. Mork, John S. Sigdestad, Jacob K. Mork, Erik Winson, Ole Aas, Ole Monson, Nels Williamson Sr., Ole Svang, Martin Davidson, Hans Anderson and Martin Anderson. In 1886, together with Webster, Grenville and Fron churches, a call was extended to candidate in theology, .C M. Nordtvedt to become their pastor. He served until the fall of 1889 when he moved to Wisconsin. Two acres of land was donated to the congregation by Anton Norby for a cemetery in 1887. It was consecrated by Rev. Nordtvedt in 1888, and the first one t& be buried there was Anfin Sand, March 13 of that year. The first infant to be baptized of families who later became Bergen Church was Serine Skaare (Mrs. Lars Mydland) in the home of John Tofley, Dec. 5,1984. And the first child of Bergen to be baptized was Selma Grove (Mrs. Rasmus Egge) in the Nels Williamson home in October, 1885. Both were baptized by Rev. Storli. The first confirmation was held by Rev. Nordtvedt June 10, 1887, when the following were confirmed: Kolben K. -

The Doctrine of the Church and Its Ministry According to the Evangelical Lutheran Synod of the Usa

THE DOCTRINE OF THE CHURCH AND ITS MINISTRY ACCORDING TO THE EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN SYNOD OF THE USA by KARL EDWIN KUENZEL Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY In the subject SYSTEMATIC THEOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: PROFESSOR ERASMUS VAN NIEKERK November 2006 ii Summary Nothing has influenced and affected the Lutheran Church in the U.S.A. in the past century more than the doctrine of the Church and its Ministry. When the first Norwegian immigrants entered the U.S. in the middle of the 19th century, there were not enough Lutheran pastors to minister to the spiritual needs of the people. Some of these immigrants resorted to a practice that had been used in Norway, that of using lay-preachers. This created problems because of a lack of proper theological training. The result was the teaching of false doctrine. Some thought more highly of the lay-preachers than they did of the ordained clergy. Consequently clergy were often viewed with a discerning eye and even despised. This was one of the earliest struggles within the Norwegian Synod. Further controversies involved whether the local congregation is the only form in which the church exists. Another facet of the controversy involves whether or not the ministry includes only the pastoral office; whether or not only ordained clergy do the ministry; whether teachers in the Lutheran schools are involved in the ministry; and whether or not any Christian can participate in the public ministry. Is a missionary, who serves on behalf of the entire church body, a pastor? If only the local congregation can call a pastor, then a missionary cannot be a pastor because he serves the entire church body in establishing new congregations. -

Hans Nielsen Hauge: a Catalyst of Literacy in Norway

NB! This is the final manuscript. In the published version there are changes in litterature and notes. HANS NIELSEN HAUGE: A CATALYST OF LITERACY IN NORWAY Linda Haukland, University of Nordland In this article, I examine the role Hans Nielsen Hauge (1771–1824) played in encouraging literacy in the Norwegian peasant society in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, an aspect of his ministry never before discussed. This poorly educated son of a peasant broke the unwritten rule of never publishing texts for a large readership without the necessary educational skills. Thus he opened up a new literate space where the common person could express him- or herself on paper. Hauge printed around 40 different texts, 14 of them books, in a language the peasants could understand. This inspired his followers not only to read, but also to write, mainly letters to Hauge and to Haugeans in other parts of Norway. Some even became authors. Women played a central role in this wave of literacy spreading throughout the country. Based on Hauge’s original texts, I present some crucial aspects of his mentality and show how his ministry served as a catalyst to the growth of literacy among peasants during the period. NB! This is the final manuscript. In the published version there are changes in litterature and notes. References Archival sources Kvamen, Ingolf, Haugianerbrev Bind 1: 1760 - 1804, Norsk Historisk Kjeldeskrift- Institutt, upublisert Universitetsbiblioteket i Trondheim (UBIT), A 0161 Per Øverland, F Haugianerne i Norge Published sources Aftenbladet December 02, 1859. In Fet, Jostein, ‘Berte Canutte Aarflot’. Store Norske leksikon. -

Ole Rynning's True Account of America

% 1 Sifhfcfartiig Ocrrtning 'i> ° i-m 21. merits j • til ©plttsriiitg OJJ llijttf for Omiiic oj itlcmrrmanti. A-orfattrt af i t>» ifyrfF, foi» torn Scrowcr i Jtini SHnnncS) 1S37. - • • 0 - "~~«»5|^g|£$g8S»™~- C Ij r't f t i it it i a. 1888. -r i . r —..',"-",, OLE RYNNING'S TRUE ACCOUNT OF AMERICA1 INTRODUCTION An intensive study of the separate immigrant groups which have streamed into America is of deep significance for an adequate understanding of our national life no less from the sociological than from the historical point of view. In tracing the expansion of population through the Mississippi Valley to the American West, the student must give careful considera tion to the part played by immigrants from the Scandinavian countries. Interest in the history of the immigration of this group and in its contributions to American life has taken various forms. The most important of these are efforts in the direction of intensive research and the collection and publica tion of the materials essential to such research. Source material abounds; yet, owing to the fact that men whose lives have spanned almost the entire period of the main movement of Norwegian immigration are still living, no clear-cut line can be traced between primary and secondary materials. Further more, the comparatively recent date of Scandinavian immigra tion to the United States has resulted in delaying the work of collecting materials relating to the movement. Recently, how ever, through the work of Flora, Babcock, Evjen, Anderson, Nelson, Norelius, Holand, and others, considerable progress has been made.2 Editors of newspapers and magazines have proved assiduous in collecting and publishing accounts of pioneers; 1 Translated and edited, with introduction and notes, by Theodore C. -

Guide to South Dakota Norwegian-American Collections

GUIDE TO COLLECTIONS RELATING TO SOUTH DAKOTA NORWEGIAN-AMERICANS Compiled by Harry F. Thompson, Ph.D. Director of Research Collections and Publications The Center for Western Studies With the assistance of Arthur R. Huseboe, Ph.D. and Paul B. Olson Additional assistance by Carol Riswold, D. Joy Harris, and Laura Plowman Originally published in 1991 by The Center for Western Studies, Augustana College, Sioux Falls, SD 57197 and updated in 2007. Original publication was made possible by a grant from the South Dakota Committee on the Humanities and by a gift from Harold L. Torness of Sisseton, South Dakota. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Albright College 2 Augustana College, The Center for Western Studies 3 Augustana College, Mikkelsen Library 4 Augustana College (IL), Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center 5 Black Hills State University 6 Brookings Public Library 7 Canton Public Library 8 Centerville Public Library 9 Codington County Historical Society 10 Cornell University Libraries 11 Dakota State University 12 Dakota Wesleyan University 13 Dewey County Library 14 Elk Point Community Library 15 Grant County Public Library 16 Phoebe Apperson Hearst Library 17 J. Roland Hove 18 Luther College 19 Minnehaha County Historical Society 20 Minnehaha County Rural Public Library 21 Minnesota Historical Society, Research Center 2 22 Mitchell Area Genealogical Society 23 Mobridge Public Library 24 National Archives--Central Plains Region 25 North Dakota State University, North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies 26 Norwegian American Historical Association 27 James B. Olson 28 Rapid City Public Library 29 Rapid City Sons of Norway Borgund Lodge I-532 30 Regional Center for Mission--Region III, ELCA 31 St. -

The Two Folk Churches in Finland

The Two Folk Churches in Finland The 12th Finnish Lutheran-Orthodox Theological Discussions 2014 Publications of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland 29 The Church and Action The Two Folk Churches in Finland The 12th Finnish Lutheran-Orthodox Theological Discussions 2014 Publications of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland 29 The Church and Action National Church Council Department for International Relations Helsinki 2015 The Two Folk Churches in Finland The 12th Finnish Lutheran-Orthodox Theological Discussions 2014 © National Church Council Department for International Relations Publications of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland 29 The Church and Action Documents exchanged between the churches (consultations and reports) Tasknumber: 2015-00362 Editor: Tomi Karttunen Translator: Rupert Moreton Book design: Unigrafia/ Hanna Sario Layout: Emma Martikainen Photos: Kirkon kuvapankki/Arto Takala, Heikki Jääskeläinen, Emma Martikainen ISBN 978-951-789-506-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-789-507-1 (PDF) ISSN 2341-9393 (Print) ISSN 2341-9407 (Online) Unigrafia Helsinki 2015 CONTENTS Foreword ..................................................................................................... 5 THE TWELFTH THEOLOGICAL DISCUSSIONS BETWEEN THE EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN CHURCH OF FINLAND AND THE ORTHODOX CHURCH OF FINLAND, 2014 Communiqué. ............................................................................................. 9 A Theological and Practical Overview of the Folk Church, opening speech Bishop Arseni ............................................................................................ -

Sverdrup Newsletter19.Pub

March 2013 The Georg Volume 10, Issue 1 Sverdrup Society NEWSLETTER 2012 GSS Annual Meeting Honors Dr. James S. Hamre The Ninth Annual Meeting of member at AFLC Schools, led In This Issue: the Georg Sverdrup Society the “Sverdrup Songfest,” in- was held October 13, 2012, at cluding “Jeg har en ven” (“I the Radisson Hotel in Fargo, Have a Friend”) and “Den 2012 GSS Annual 1 North Dakota, the site of the Himmelske Lovsang” (“The Meeting Honors Hamre Georg Sverdrup Society’s Heavenly Hymn”). The latter “Sven Oftedal” Study 1 organization in December came to Madagascar with Choice for 2013 2003. The first annual meet- Norwegian missionaries and ing was also held there in is still sung by Malagasy car- “Sverdrup and 3 Controversy October 2004. olers each Easter Sunday Discussion Forum This year’s program was morning at sunrise. After the organized as a tribute to Dr. audience had sung a verse in Photos 4 James S. Hamre, an inspira- Norwegian, Pastor Lee asked Dr. James S. Hamre (left) tion and guide to the society Mrs. Karen Knudsvig, who receives a plaque from GSS “It Is Finished” 4 for the past decade. Rev. served on the mission field in Pres. Loiell Dyrud, “For a Life- Translation Terry Olson of Grand Forks, Madagascar, to sing a verse in time Devoted to Preserving the Legacy of Georg Sverdrup” at North Dakota, gave the Invo- Malagasy. It was a reminder cation. to everyone of Sverdrup’s the Annual Meeting in Fargo. Rev. Robert Lee, faculty (continued on page 2) “Sven Oftedal” Choice for Study in 2013 Georg Sverdrup Georg Sverdrup and Sven Prof. -

The Large Catechism by Martin Luter

The Large Catechism By Dr. Martin Luther Translated by F. Bente and W. H. T. Dau Essay on Martin Luther and Protestantism Published in: Triglot Concordia: The Symbolical Books of the Ev. Lutheran Church. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1921), pp. 565-773 Preface A Christian, Profitable, and Necessary Preface and Faithful, Earnest Exhortation of Dr. Martin Luther to All Christians, but Especially to All Pastors and Preachers, that They Should Daily Exercise Themselves in the Catechism, which is a Short Summary and Epitome of the Entire Holy Scriptures, and that they May Always Teach the Same. We have no slight reasons for treating the Catechism so constantly [in Sermons] and for both desiring and beseeching others to teach it, since we see to our sorrow that many pastors and preachers are very negligent in this, and slight both their office and this teaching; some from great and high art [giving their mind, as they imagine, to much higher matters], but others from sheer laziness and care for their paunches, assuming no other relation to this business than if they were pastors and preachers for their bellies’ sake, and had nothing to do but to [spend and] consume their emoluments as long as they live, as they have been accustomed to do under the Papacy. And although they have now everything that they are to preach and teach placed before them so abundantly, clearly, and easily, in so many [excellent and] helpful books, and the true Sermones per se loquentes, Dormi secure, Paratos et Thesauros, as they were called in former times; yet they are not so godly and honest as to buy these books, or even when they have them, to look at them or read them. -

Logia 4/03 Text W/O

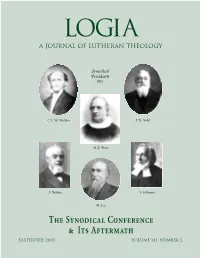

Logia a journal of lutheran theology Synodical Presidents C. F. W. Walther J. H. Sieker H. A. Preus J. Bading F. Erdmann M. Loy T S C I A eastertide 2003 volume xii, number 2 ei[ ti" lalei', wJ" lovgia Qeou' logia is a journal of Lutheran theology. As such it publishes articles on exegetical, historical, systematic, and liturgical theolo- T C A this issue shows the presidents of gy that promote the orthodox theology of the Evangelical the synods that formed the Evangelical Lutheran Lutheran Church. We cling to God’s divinely instituted marks of Synodical Conference (formed July at the church: the gospel, preached purely in all its articles, and the Milwaukee, Wisconsin). They include the sacraments, administered according to Christ’s institution. This Revs. C. F. W. Walther (Missouri), H. A. Preus name expresses what this journal wants to be. In Greek, LOGIA (Norwegian), J. H. Sieker (Minnesota), J. Bading functions either as an adjective meaning “eloquent,”“learned,” or (Wisconsin), M. Loy (Ohio), F. Erdmann (Illinois). “cultured,” or as a plural noun meaning “divine revelations,” “words,”or “messages.”The word is found in Peter :, Acts :, Pictures are from the collection of Concordia oJmologiva and Romans :. Its compound forms include (confes- Historical Institute, Rev. Mark A. Loest, assistant ajpologiva ajvnalogiva sion), (defense), and (right relationship). director. Each of these concepts and all of them together express the pur- pose and method of this journal. LOGIA considers itself a free con- ference in print and is committed to providing an independent L is indexed in the ATLA Religion Database, published by the theological forum normed by the prophetic and apostolic American Theological Library Association, Scriptures and the Lutheran Confessions. -

Lutheran Synod Quarterly

LUTHERAN SYNOD QUARTERLY VOLUME 52 • NUMBERS 2-3 JUNE–SEPTEMBER 2012 The theological journal of Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary LUTHERAN SYNOD QUARTERLY EDITOR-IN-CHIEF........................................................... Gaylin R. Schmeling BOOK REVIEW EDITOR ......................................................... Michael K. Smith LAYOUT EDITOR ................................................................. Daniel J. Hartwig PRINTER ......................................................... Books of the Way of the Lord FACULTY............. Adolph L. Harstad, Thomas A. Kuster, Dennis W. Marzolf, Gaylin R. Schmeling, Michael K. Smith, Erling T. Teigen The Lutheran Synod Quarterly (ISSN: 0360-9685) is edited by the faculty of Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary 6 Browns Court Mankato, Minnesota 56001 The Lutheran Synod Quarterly is a continuation of the Clergy Bulletin (1941–1960). The purpose of the Lutheran Synod Quarterly, as was the purpose of the Clergy Bulletin, is to provide a testimony of the theological position of the Evangelical Contents Lutheran Synod and also to promote the academic growth of her clergy roster by providing scholarly articles, rooted in the inerrancy of the Holy Scriptures and the LSQ Vol. 52, Nos. 2–3 (June–September 2012) Confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. ARTICLES AND SERMONS The Lutheran Synod Quarterly is published in March and December with a “God Has Gone Up With a Shout” - An Exegetical Study of combined June and September issue. Subscription rates are $25.00 U.S. per year -

This Is a Self-Archived Version of an Original Article. This Version May Differ from the Original in Pagination and Typographic Details

This is a self-archived version of an original article. This version may differ from the original in pagination and typographic details. Author(s): Mangeloja, Esa Title: Religious Revival Movements and the Development of the Twentieth-century Welfare- state in Finland Year: 2019 Version: Published version Copyright: © 2019 the Authors Rights: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Rights url: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Please cite the original version: Mangeloja, E. (2019). Religious Revival Movements and the Development of the Twentieth- century Welfare-state in Finland. In K. Sinnemäki, A. Portman, J. Tilli, & R. Nelson (Eds.), On the Legacy of Lutheranism in Finland : Societal Perspectives (pp. 220-236). Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Studia Fennica Historica, 25. https://oa.finlit.fi/site/books/10.21435/sfh.25/ On the Legacy of Lutheranism in Finland Societal Perspectives Edited by Kaius Sinnemäki, Anneli Portman, Jouni Tilli and Robert H. Nelson Finnish Literature Society Ü SKS Ü Helsinki Ü 2019 studia fennica historica 25 The publication has undergone a peer review. © 2019 Kaius Sinnemäki, Anneli Portman, Jouni Tilli, Robert H. Nelson and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB: Tero Salmén ISBN 978-951-858-135-5 (Print) ISBN 978-951-858-150-8 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-858-149-2 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica. Print) ISSN 2669-9605 (Studia Fennica. Online) ISSN 1458-526X (Studia Fennica Historica. Print) ISSN 2669-9591 (Studia Fennica Historica. Online) DOI: https://doi.org/10.21435/sfh.25 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License. -

Folk I Nord Møtte Prester Fra Sør Kirke- Og Skolehistorie, Minoritets- Og

KÅRE SVEBAK Folk i Nord møtte prester fra sør Kirke- og skolehistorie, minoritets- og språkpolitikk En kildesamling: 65 LIVHISTORIER c. 1850-1970 KSv side 2 INNHOLDSREGISTER: FORORD ......................................................................................................................................... 10 FORKORTELSER .............................................................................................................................. 11 SKOLELOVER OG INSTRUKSER........................................................................................................ 12 RAMMEPLAN FOR DÅPSOPPLÆRING I DEN NORSKE KIRKE ........................................................... 16 INNLEDNING .................................................................................................................................. 17 1. BERGE, OLE OLSEN: ................................................................................... 26 KVÆFJORD, BUKSNES, STRINDA ....................................................................................................... 26 BUKSNES 1878-88 .......................................................................................................................... 26 2. ARCTANDER, OVE GULDBERG: ................................................................... 30 RISØR, BUKSNES, SORTLAND, SOGNDAL, SIGDAL, MANDAL .................................................................. 30 RISØR 1879-81 ..............................................................................................................................