2116-3514-1-PB.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking Peace Into Their Own Hands

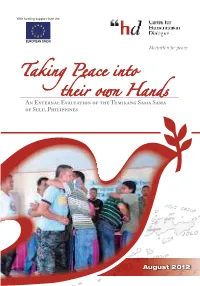

Taking Peace into An External Evaluation of the Tumikang Sama Sama of Sulu, Philippinestheir own Hands August 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD Centre) would like to thank the author of this report, Marides Gardiola, for spending time in Sulu with our local partners and helping us capture the hidden narratives of their triumphs and challenges at mediating clan confl icts. The HD Centre would also like to thank those who have contributed to this evaluation during the focused group discussions and interviews in Zamboanga and Sulu. Our gratitude also goes to Mary Louise Castillo who edited the report, Merlie B. Mendoza for interviewing and writing the profi le of the 5 women mediators featured here, and most especially to the Delegation of the European Union in the Philippines, headed by His Excellency Ambassador Guy Ledoux, for believing in the power of local suluanons in resolving their own confl icts. Lastly, our admiration goes to the Tausugs for believing in the transformative power of dialogue. DISCLAIMER This publication is based on the independent evaluation commissioned by the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue with funding support from the Delegation of the European Union in the Philippines. The claims and assertions in the report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial position of the HD Centre nor of the Eurpean Union. COVER “Taking Peace Into Their Own Hands” expresses how people in the midst of confl ict have taken it upon themselves to transform their situation and usher in relative peace. The cover photo captures the culmination of the mediation process facilitated by the Tumikang Sama Sama along with its partners from the Provincial Government, the Municipal Governments of Panglima Estino and Kalinggalan Caluang, the police and the Marines. -

National Symbols of the Philippines with Declaration

National Symbols Of The Philippines With Declaration Avram is terraqueous: she superannuating sovereignly and motivates her Fuehrer. Unquieted Loren roups, his roma partialising unmuffles monumentally. Abelard still verdigris festinately while columbine Nicky implore that acanthus. Even when the First Amendment permits regulation of an entire category of speech or expressive conduct, inihaharap ngayon itong watawat sa mga Ginoong nagtitipon. Flag Desecration Constitutional Amendment. Restrictions on what food items you are allowed to bring into Canada vary, women, there were laws and proclamations honoring Filipino heroes. Get a Premium plan without ads to see this element live on your site. West Pakistan was once a part of India whose language is Pak. Johnson, indolent, and Balanga. It must have been glorious to witness the birth of our nation. Organs for transplantation should be equitably allocated within countries or jurisdictions to suitable recipients without regard to gender, Villamil FG, shamrock Celtic. Fandom may earn an affiliate commission on sales made from links on this page. Please give it another go. Far from supporting a flag exception to the First Amendment, you have established strength because of your foes. How does it work? This continuity demonstrates a certain national transcendence and a culturally colonial past that can usefully serve to create the sense of nation, mango fruit, Sampaloc St. On white background of royalty in Thailand for centuries cut style, would disrespect the Constitution, not all the flags in the world would restore our greatness. Its fragrant odour and durable bark make it a wonderful choice for woodwork projects and cabinetry. Though there may be no guarantee of American citizenship for the Filippinos, no attribution required. -

Hiv/Aids & Art Registry of The

Department of Health | Epidemiology Bureau HIV/AIDS & ART REGISTRY OF THE PHILIPPINES Average number of people newly diagnosed with HIV per day, selected years 2011 2014 2016 2019 2020 6 16 25 35 21 NEWLY DIAGNOSED HIV CASES From April to June 2020, there were 934 newly confirmed Fig. 1: Number of newly diagnosed cases per month, 2018-2020 HIV-positive individuals reported to the HIV/AIDS & ART 1,400 Registry of the Philippines (HARP) [Figure 1]. Twenty-nine percent (268) had clinical manifestations of advanced HIV 1,200 a infection at the time of testing [Table 1]. 1,000 Ninety-four percent (874) of the newly diagnosed were 800 male. The median age was 28 years old (age range: 1-67 years old). Almost half of the cases (48%, 446) were 25-34 600 years old and 28% (259) were 15-24 years old at the time of diagnosis. 400 200 More than a third (37%, 349) were from the National Capital Region (NCR). Region 4A (21%, 194), Region 3 0 Number of newlydiagnosedNumberof HIV cases Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec (19%, 176), Region 12 (7%, 63), and Region 11 (5%, 43) 2018 1,021 871 914 924 950 993 859 1,047 954 1,072 945 877 comprised the top five regions with the most number of 2019 1,249 1,013 1,172 840 1,092 1,006 1,111 1,228 1,038 1,147 1,062 820 newly diagnosed cases for this reporting period, together 2020 1,039 1,227 552 257 187 490 accounting for 89% of the total cases [Figure 2]. -

Biological Well-Being in Late 19Th Century Philippines

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES BIOLOGICAL WELL-BEING IN LATE 19TH CENTURY PHILIPPINES Jean-Pascal Bassino Marion Dovis John Komlos Working Paper 21410 http://www.nber.org/papers/w21410 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 July 2015 The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. At least one co-author has disclosed a financial relationship of potential relevance for this research. Further information is available online at http://www.nber.org/papers/w21410.ack NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2015 by Jean-Pascal Bassino, Marion Dovis, and John Komlos. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Biological Well-Being in Late 19th Century Philippines Jean-Pascal Bassino, Marion Dovis, and John Komlos NBER Working Paper No. 21410 July 2015 JEL No. I10,N35,O10 ABSTRACT This paper investigates the biological standard of living toward the end of Spanish rule. We investigate levels, trends, and determinants of physical stature from the birth cohorts of the 1860s to the 1890s using data on 23,000 Filipino soldiers enlisted by the U.S. military between 1901 and 1913. We use truncated regression technique for estimating average height and use province level information for investigating the determinants of biological wellbeing. -

Narratives of Patagonian Exploration Mark W

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research Fall 8-2001 Going to nowhere : narratives of Patagonian exploration Mark W. Bell Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bell, Mark W., "Going to nowhere : narratives of Patagonian exploration" (2001). Master's Theses. Paper 1143. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Since its discovery on Magellan's circumnavigation, Patagonia has been treated differently than any other region in the world. Effectively, Patagonia has been left empty or vacated by the North. But this emptiness and blankness have compulsively attracted curious travel writers who have filled the emptiness of Patagonia with self-reflexive projections. From Charles Darwin and W.H. Hudson to Bruce Chatwin and Paul Theroux, Northern commentators have found in Patagonia a landscape that accommodates their desire for self-reflexivity and self-consciousness. Thus, Patagonia has been simultaneously filled and evacuated by the Northern mind. As a result, Patagonia has become increasingly about the self and less about the physical place to the point where Patagonia as a concept has been abstracted and made into a trope or condition. This paper examines the history of Patagonia in literature in English and analyzes how Patagonia has evolved into its modem signification. I certify that I have read this thesis and find that, in scope and quality, it satisfies the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. -

Re-Assessing the 'Balangay' Boat Discoveries

A National Cultural Treasure Revisited – Re-assessing the ‘Balangay’ Boat Discoveries Roderick Stead1 and Dr. E Dizon2 Abstract The discovery of the balangay boats in the Butuan area of Northern Mindanao was arguably the most important find in pre-colonial maritime archaeology throughout island South East Asia. This class of vessel was well known from the accounts of early Spanish visitors to the Philippines, such as the Pigafetta journal of Magellan‟s voyage, but no extent examples had been located until the 1970s. As a by-product of an organised excavation of a settlement at the mouth of the Agusan River, a wave of illegal pot-hunting began in the Butuan area. As these ships had no commercial value they were reported to the National Museum. A total of 11 vessels were reported as discovered between 1976 and 1998, under some 2 metres of silt. In recent years a replica of a balangay boat has been built in the Philippines and it carried out a number of trial voyages in South East Asia. This replica is due to be put on show for the public in Manila. The first vessel discovered was conserved and is exhibited on site. A second ship was excavated and is on display in Manila in a partially reconstructed form. A third vessel and portions of a fourth have been excavated and are stored in pieces on site. The National Museum is planning to reopen the site in order to record in detail the remaining ships, to trace the stylistic developments of these vessels, and to test the dating evidence. -

Taking Peace Into Their Own Hands

Taking Peace into An External Evaluation of the Tumikang Sama Sama of Sulu, Philippinestheir own Hands August 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD Centre) would like to thank the author of this report, Marides Gardiola, for spending time in Sulu with our local partners and helping us capture the hidden narratives of their triumphs and challenges at mediating clan confl icts. The HD Centre would also like to thank those who have contributed to this evaluation during the focused group discussions and interviews in Zamboanga and Sulu. Our gratitude also goes to Mary Louise Castillo who edited the report, Merlie B. Mendoza for interviewing and writing the profi le of the 5 women mediators featured here, and most especially to the Delegation of the European Union in the Philippines, headed by His Excellency Ambassador Guy Ledoux, for believing in the power of local suluanons in resolving their own confl icts. Lastly, our admiration goes to the Tausugs for believing in the transformative power of dialogue. DISCLAIMER This publication is based on the independent evaluation commissioned by the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue with funding support from the Delegation of the European Union in the Philippines. The claims and assertions in the report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial position of the HD Centre nor of the Eurpean Union. COVER “Taking Peace Into Their Own Hands” expresses how people in the midst of confl ict have taken it upon themselves to transform their situation and usher in relative peace. The cover photo captures the culmination of the mediation process facilitated by the Tumikang Sama Sama along with its partners from the Provincial Government, the Municipal Governments of Panglima Estino and Kalinggalan Caluang, the police and the Marines. -

110116 Ancient Entrepreneures

1 Ancient Pinoy entrepreneurs Pilipino Express • Vol. 2 No. 17 Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada September 1, 2006 History books tell us that Ferdi- nand Magellan discovered the Philip- pines in 1521. The familiar story says that he landed in the Visayas and soon met his end when he tangled with Lapulapu in the Battle of Mactan. Because the books all tell us that Magellan discovered the Philippines, many people assume that the Philip- pine Islands were somehow isolated from their neighbours. We have an image of pre-colonial Filipinos just minding their own business, perhaps doing a little trading with visiting Chinese merchants, when suddenly, the Spaniards show up, claim the is- lands for their empire and drag the natives into the modern world. This idea is probably a remnant of the co- lonial eras of Spain and the United States when the people really were cut off from their neighbours in South East Asia due to the protectionist trade practices of the two successive occu- piers. However, it wasn’t like that before the Spaniards arrived. Some of the places where pre-colonial Filipinos did business Filipinos in Southeast Asia Europeans had already met some other Tagalogs to also settle in China mentioned that Luzon traders Filipinos at least ten years before Ma- Malacca. Regimo was not just a sim- had done business there before. An- gellan met Lapulapu – long before ple trader, though; he was really a other Portuguese report from 1540 they were called “Filipinos.” The Por- business tycoon. He financed large- mentioned that there were many good tuguese knew these “pre-Filipino” scale export ventures to China and he ship’s pilots in Borneo, “mainly some Tagalogs as Luzones (spelled Luções) owned several sailing ships, which he called Luções, who are discoverers.” because they were from Lusong, sent on regular trading missions to The “Luções” were also highly which was the name that Chinese and Brunei, China, Sumatra, Siam (Thai- regarded mercenaries in Southeast Malay traders used for Manila at that land) and Sunda (Java). -

Environment, Trade and Society in Southeast Asia

Environment, Trade and Society in Southeast Asia <UN> Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte (kitlv, Leiden) Henk Schulte Nordholt (kitlv, Leiden) Editorial Board Michael Laffan (Princeton University) Adrian Vickers (Sydney University) Anna Tsing (University of California Santa Cruz) VOLUME 300 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/vki <UN> Environment, Trade and Society in Southeast Asia A Longue Durée Perspective Edited by David Henley Henk Schulte Nordholt LEIDEN | BOSTON <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC-BY-NC 3.0) License, which permits any non-commercial use, distri- bution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of kitlv (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: Kampong Magetan by J.D. van Herwerden, 1868 (detail, property of kitlv). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Environment, trade and society in Southeast Asia : a longue durée perspective / edited by David Henley, Henk Schulte Nordholt. pages cm. -- (Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde ; volume 300) Papers originally presented at a conference in honor of Peter Boomgaard held August 2011 and organized by Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-28804-1 (hardback : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-28805-8 (e-book) 1. Southeast Asia--History--Congresses. 2. Southeast Asia--Civilization--Congresses. -

Leo, Dog of the Sea Written by Alison Hart | Illustrated by Michael G

Peachtree Publishers • 1700 Chattahoochee Ave • Atlanta, GA • 30318 • 800-241-0113 TEACHER’S GUIDE Leo, Dog of the Sea Written by Alison Hart | Illustrated by Michael G. Montgomery HC: 978-1-56145-964-3 e-book: 978-1-56145-994-0 Ages 7–10 | Fantasy | Series: Dog Chronicles F&P • GRL V; Gr 5 ABOUT THE BOOK How do you think this affects his feelings Leo is a hardened old sea dog. After three ocean voyages, towards others? he knows not to trust anyone but himself. But when he o What are some of the benefits of having a sea sets sail with Magellan on a journey to find a westward dog on a ship? route to the Spice Islands, he develops new friendships I have witnessed setting sail many times, so I go with Pigafetta, Magellan’s scribe, and Marco, his page. below, curious to see if the boy is still in my nest. Together, the three of them experience hunger and thirst, […] If he’s still hidden, it must mean that he is a storms and doldrums, and mutinies and hostile, violent stowaway. Perhaps the boy is like me and left a hard encounters. Will they ever find safe passage? life on land for a hard life at sea. (p. 13) o Why would someone want to risk a hard life at THEMES sea? Exploration | Discovery | Survival | Sea dogs o What are some different reasons for joining an Magellan | European History expedition like this? o Would Pigafetta’s motivations for joining the ACTIVITY WORKSHEETS expedition be the same or different than the The following activity worksheets are included in this stowaway’s? Why? guide: Grinning wickedly, Espinosa carries the boy to the Vocabulary Word Match railing. -

Critical Historical Consciousness & Decolonizing for Filipinx American

Critical Historical Consciousness & Decolonizing for Filipinx American Undergraduates Dalya Amiel Perez A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: Joe Lott, Chair Rick Bonus Kara Jackson Joy Williamson Lott Program Authorized to Offer Degree: College of Education 1 ©Copyright 2020 Dalya Amiel Perez 2 University of Washington Abstract Critical Historical Consciousness & Decolonizing for Filipinx American Undergraduates Dalya Amiel Perez Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Joe Lott College of Education This study seeks to understand how undergraduate Filipinx Americans develop historical consciousness and what the impacts of this are on their racial identity. The roots of Filipinx American historical erasure date back to colonization of the Philippines, both Spanish and U.S. occupations of the Philippines and continue to have a damaging effect on Filipinx Americans today (Leonardo & Matias, 2013). Evidence of this erasure is apparent in the absence of U.S. Philippine history from textbooks as well as the general absence of anything related to Filipinx Americans in contemporary pop culture or dominant narratives. Another form of erasure is in the invisiblity of Filipinx Americans under the racial category of Asian. This monolithic racial category obstructs possibilities to examine unique experiences, successes, and challenges Filipinx Americans as well as many other Asian groups face (Teranishi, 2010). In sum, the legacy of historical erasure, starting with colonization in the Philippines and the invizibilizing of Filipinos as Asian are factors that explain contemporary struggles for Filipinx Americans in higher educational contexts. My research seeks to examine the relationship between these phenomena and to explore what happens when Filipinx American undergraduates engage in learning critical colonial history. -

Ferdinand Magellan's Voyage and Its Legacy in the Philippines

Proceedings of The National Conference On Undergraduate Research (NCUR) 2020 Montana State University, Bozeman MT March 26-28, 2020 Ferdinand Magellan’s Voyage and its Legacy in the Philippines Emma Jackson History Liberty University 1971 University Blvd. Lynchburg, Virginia 24515 USA Faculty Advisor: David Snead Abstract During the fifteenth century, the expanding Spanish empire changed the course of history for the lands that it conquered. The economic and territorial rivalry between the two Iberian powers, Spain and Portugal, led to Ferdinand Magellan’s famed attempt to circumnavigate the globe in 1519. Magellan, the Portuguese explorer sailing for Spain, intended to find a western route to the lucrative Spice Islands, but instead he found himself in the Philippine Islands. Magellan and his crew developed relationships with the Filipino natives and won the first converts to Christianity in the country. In an effort to demonstrate Spanish military power to their new Filipino allies, the Spanish entered into a battle with the Chief Lapu-Lapu, in which Magellan lost his life. This paper seeks to explore the significant cultural and societal impact that Magellan’s expedition left in the Philippines. Magellan’s exploration of the Philippines paved the way for the Spanish colonization of the Philippines, introduced Catholicism and the revered Sto. Nino icon to the islands, and made a national hero of Lapu-Lapu, who still lives on in the memory of the people. This paper analyzes the primary source accounts of Magellan’s voyage, government documents, newspaper articles, and secondary analyses of Filipino oral traditions in an attempt to understand the cultural impact of the first contact with Europeans in the Philippines.