Ferdinand Magellan's Voyage and Its Legacy in the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Straits of Magellan Were the Final Piece in in Paris

Capítulo 1 A PASSAGE TO THE WORLD The Strait of Magellan during the Age of its Discovery Mauricio ONETTO PAVEZ 2 3 Mauricio Onetto Paves graduated in 2020 will be the 500th anniversary of the expedition led by history from the Pontifical Catholic Ferdinand Magellan that traversed the sea passage that now carries his University of Chile. He obtained name. It was an adventure that became part of the first circumnavigation his Masters and PhD in History and of the world. Civilizations from the L’École des Ever since, the way we think about and see the world – and even the Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales universe – has changed. The Straits of Magellan were the final piece in in Paris. a puzzle that was yet to be completed, and whose resolution enabled a He is the director of the international series of global processes to evolve, such as the movement of people, academic network GEOPAM the establishment of commercial routes, and the modernization of (Geopolítica Americana de los siglos science, among other things. This book offers a new perspective XVI-XVII), which focuses on the for the anniversary by means of an updated review of the key event, geopolitics of the Americas between based on original scientific research into some of the consequences of the 16th and 17th centuries. His negotiating the Straits for the first time. The focus is to concentrate research is funded by Chile’s National on the geopolitical impact, taking into consideration the diverse scales Fund for Scientific and Technological involved: namely the global scale of the world, the continental scale Development (FONDECYT), and he of the Americas, and the local context of Chile. -

Cebu 1(Mun to City)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of Cebu Province i Map of Cebu City ii - iii Map of Mactan Island iv Map of Cebu v A. Overview I. Brief History................................................................... 1 - 2 II. Geography...................................................................... 3 III. Topography..................................................................... 3 IV. Climate........................................................................... 3 V. Population....................................................................... 3 VI. Dialect............................................................................. 4 VII. Political Subdivision: Cebu Province........................................................... 4 - 8 Cebu City ................................................................. 8 - 9 Bogo City.................................................................. 9 - 10 Carcar City............................................................... 10 - 11 Danao City................................................................ 11 - 12 Lapu-lapu City........................................................... 13 - 14 Mandaue City............................................................ 14 - 15 City of Naga............................................................. 15 Talisay City............................................................... 16 Toledo City................................................................. 16 - 17 B. Tourist Attractions I. Historical........................................................................ -

The Sphingidae (Lepidoptera) of the Philippines

©Entomologischer Verein Apollo e.V. Frankfurt am Main; download unter www.zobodat.at Nachr. entomol. Ver. Apollo, Suppl. 17: 17-132 (1998) 17 The Sphingidae (Lepidoptera) of the Philippines Willem H o g e n e s and Colin G. T r e a d a w a y Willem Hogenes, Zoologisch Museum Amsterdam, Afd. Entomologie, Plantage Middenlaan 64, NL-1018 DH Amsterdam, The Netherlands Colin G. T readaway, Entomologie II, Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, Senckenberganlage 25, D-60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Abstract: This publication covers all Sphingidae known from the Philippines at this time in the form of an annotated checklist. (A concise checklist of the species can be found in Table 4, page 120.) Distribution maps are included as well as 18 colour plates covering all but one species. Where no specimens of a particular spe cies from the Philippines were available to us, illustrations are given of specimens from outside the Philippines. In total we have listed 117 species (with 5 additional subspecies where more than one subspecies of a species exists in the Philippines). Four tables are provided: 1) a breakdown of the number of species and endemic species/subspecies for each subfamily, tribe and genus of Philippine Sphingidae; 2) an evaluation of the number of species as well as endemic species/subspecies per island for the nine largest islands of the Philippines plus one small island group for comparison; 3) an evaluation of the Sphingidae endemicity for each of Vane-Wright’s (1990) faunal regions. From these tables it can be readily deduced that the highest species counts can be encountered on the islands of Palawan (73 species), Luzon (72), Mindanao, Leyte and Negros (62 each). -

1TT Ilitary ISTRICT 15 APRIL 1944 ENERAL HEADQU Rtilrs SQUI WES F2SPA LCEIC AREA Mitiaryi Intcligee Sectionl Ge:;;Neral Staff

. - .l AU 1TT ILiTARY ISTRICT 15 APRIL 1944 ENERAL HEADQU RTiLRS SQUI WES F2SPA LCEIC AREA Mitiaryi IntcligeE Sectionl Ge:;;neral Staff MINDA NAO AIR CENTERS 0) 5 0 10 20 30 SCALE IN MILS - ~PROVI~CIAL BOUNDARIEtS 1ST& 2ND CGLASS ROADIS h A--- TRAILS OPERATIONAL AIRDROMES O0 AIRDROMES UNDER CONSTRUCTION 0) SEAPLANE BASES (KNO N) _ _ _ _ 2 .__. ......... SITUATION OF FRIENDLY AR1'TED ORL'S IN TIDE PHILIPPINES 19 Luzon, Mindoro, Marinduque and i asbate: a) Iuzon: Pettit, Shafer free Luzon, Atwell & Ramsey have Hq near Antipolo, Rizal, Frank Johnson (Liguan Coal Mines), Rumsel (Altaco Transport, Rapu Rapu Id), Dick Wisner (Masbate Mines), all on Ticao Id.* b) IlocoseAbra: Number Americans free this area.* c) Bulacan: 28 Feb: 40 men Baliuag under Lt Pacif ico Cabreras. 8ev guerr loaders Bulacan, largest being under Lorenzo Villa, ox-PS, 1"x/2000 well armed men in "77th Regt".., BC co-op w/guerr thruout the prov.* d) Manila: 24 Mar: FREE PHILIPPITS has excellent coverage Manila, Bataan, Corregidor, Cavite, Batangas, Pampanga, Pangasinan, Tayabas, La Union, and larger sirbases & milit installations.* e) Tayabas: 19 Mar: Gen Gaudencia Veyra & guerr hit 3 towns on Bondoc Penin: Catanuan, Macal(lon & Genpuna && occu- pied them. Many BC reported killed,* f) icol Peninsula : 30 Mar: Oupt Zabat claims to have uni-s fied all 5th MD but Sorsogon.* g) Masbate: 2 Apr Recd : Villajada unit killed off by i.Maj Tanciongco for bribe by Japs.,* CODvjTNTS: (la) These men, but Ramsey, not previously reported. Ramsey previously reported in Nueva Ecija. (lb) Probably attached to guerrilla forces under Gov, Ablan. -

DOWNLOAD Primerang Bituin

A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim Copyright 2006 Volume VI · Number 1 15 May · 2006 Special Issue: PHILIPPINE STUDIES AND THE CENTENNIAL OF THE DIASPORA Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Philippine Studies and the Centennial of the Diaspora: An Introduction Graduate Student >>......Joaquin L. Gonzalez III and Evelyn I. Rodriguez 1 Editor Patricia Moras Primerang Bituin: Philippines-Mexico Relations at the Dawn of the Pacific Rim Century >>........................................................Evelyn I. Rodriguez 4 Editorial Consultants Barbara K. Bundy Hartmut Fischer Mail-Order Brides: A Closer Look at U.S. & Philippine Relations Patrick L. Hatcher >>..................................................Marie Lorraine Mallare 13 Richard J. Kozicki Stephen Uhalley, Jr. Apathy to Activism through Filipino American Churches Xiaoxin Wu >>....Claudine del Rosario and Joaquin L. Gonzalez III 21 Editorial Board Yoko Arisaka The Quest for Power: The Military in Philippine Politics, 1965-2002 Bih-hsya Hsieh >>........................................................Erwin S. Fernandez 38 Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Mark Mir Corporate-Community Engagement in Upland Cebu City, Philippines Noriko Nagata >>........................................................Francisco A. Magno 48 Stephen Roddy Kyoko Suda Worlds in Collision Bruce Wydick >>...................................Carlos Villa and Andrew Venell 56 Poems from Diaspora >>..................................................................Rofel G. Brion -

The Filipino Ringside Community: National Identity and the Heroic

THE FILIPINO RINGSIDE COMMUNITY : NATIONAL IDENTITY AND THE HEROIC MYTH OF MANNY PACQUIAO A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication, Culture and Technology By Margaret Louise Costello, B.A. Washington, DC April 30, 2009 THE FILIPINO RINGSIDE COMMUNITY : NATIONAL IDENTITY AND THE HEROIC MYTH OF MANNY PACQUIAO Margaret Louise Costello, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Mirjana Dedaic, PhD ABSTRACT One of the main parallels between sport and national identity is that they are both maintained by ritual and symbolism. In the Philippine context, the spectator sport of boxing has grown to be a phenomenon in recent years, perhaps owing to the successive triumphs of contemporary Filipino pugilists in the international boxing scene. This thesis focuses on the case of Filipino boxer Manny Pacquiao whose matches bring together contemporary Philippine society into a “ringside community”, a collective united by its support of a single fighter bearing the brunt for the nation. I assert that Pacquiao’s stature has transcended that of the sports realm, as he is constructed as a national (i.e., not just sport) hero. As such, I study this phenomenon in two ways. The first part of my analysis focuses on how a narrative of heroism has been instilled in Philippine society through the active promotion of its past heroes. Inherent to this study’s discussion of the Filipino ringside community and heroism is the notion of the habitus. Defined by Pierre Bourdieu as a set of inculcated dispositions which generate practices and perceptions, “a present past that tends to perpetuate itself into the future by reactivation in similarly structured practices” (Bourdieu, 6), the concept of habitus can be directly applied to how the need for a heroic narrative has been inculcated within Philippine contemporary society. -

Mactan Cebu International Passenger Terminal Project (Philippines)

Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors Project Number : 48271-001 November 2014 Proposed Loan GMR Megawide Cebu Airport Corporation Mactan Cebu International Passenger Terminal Project (Philippines) This is an abbreviated version of the document approved by ADB's Board of Directors that excludes information that is subject to exceptions to disclosure set forth in ADB's Public Communications Policy 2011. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 1 October 2014) Currency unit – peso/s (P) P1.00 = $0.02225 $1.00 = P44.94 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank DOTC – Department of Transportation and Communication EMP – environmental management plan EPC – engineering, procurement, and construction GDP – gross domestic product GIL – GMR Infrastructure Ltd GMCAC – GMR Megawide Cebu Airport Corporation IEE – initial environmental examination MCC – Megawide Construction Corporation MCIA – Mactan Cebu International Airport MCIAA – Mactan Cebu International Airport Authority mppa – million passengers per annum PPP – public–private partnership TA – technical assistance NOTES (i) The fiscal year of GMR Megawide Cebu Airport Corporation ends on 31 December. (ii) In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. Vice -President L. Venkatachalam, Private Sector and Cofinancing Operations Director General T. Freeland, Private Sector Operations Department (PSOD) Director C. Thieme, Infrastructure Finance Division 2, PSOD Team leader C. Uy, Investment Specialist, PSOD Team members S. Durrani Jamal, Senior Economist, PSOD C. Gin, Principal Counsel, -

2116-3514-1-PB.Pdf

philippine studies Ateneo de Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines The Mediterranean Connection William Henry Scott Philippine Studies vol. 37, no. 2 (1989) 131–144 Copyright © Ateneo de Manila University Philippine Studies is published by the Ateneo de Manila University. Contents may not be copied or sent via email or other means to multiple sites and posted to a listserv without the copyright holder’s written permission. Users may download and print articles for individual, noncom- mercial use only. However, unless prior permission has been obtained, you may not download an entire issue of a journal, or download multiple copies of articles. Please contact the publisher for any further use of this work at [email protected]. http://www.philippinestudies.net Philippine Studies 37 (1989):131-44 The Mediterranean Connection WILLIAM HENRY SCOTT When Magellan's ships and survivors left Philippine waters in 1521 following his death in Mactan, they proceeded to Borneo where, at the mouth of Brunei Bay, they seized a ship commanded by a Filipino prince who fifty years later would be known as Rajah Matanda. He was quietly released after bribing the Spanish commander, but seventeen others of his company were retained for their value as guides, pilots or interpreters or, in the case of three females, for other virtues. One of these was a slave who could speak Spanish or, more accu- rately, "a Moor who understood something of our Castilian language, who was called Pazeculan."l A later account identifies this slave as a pilot and a Makassarese who, "after having been captured and passed from one master to another, had wound up in the service of the prince of L~zon."~His special linguistic proficiency may have been the result of the vicissitudes of his captivity, and so may his faith, since Makassar did not adopt Islam until the next century. -

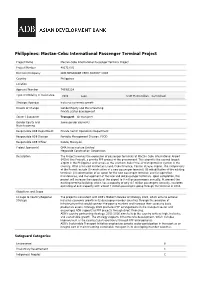

Mactan-Cebu International Passenger Terminal Project

Philippines: Mactan-Cebu International Passenger Terminal Project Project Name Mactan-Cebu International Passenger Terminal Project Project Number 48271-001 Borrower/Company GMR MEGAWIDE CEBU AIRPORT CORP Country Philippines Location Approval Number 7439/3224 Type or Modality of Assistance 7439 Loan USD 75.00 million Committed Strategic Agendas Inclusive economic growth Drivers of Change Gender Equity and Mainstreaming Private sector development Sector / Subsector Transport - Air transport Gender Equity and Some gender elements Mainstreaming Responsible ADB Department Private Sector Operations Department Responsible ADB Division Portfolio Management Division, PSOD Responsible ADB Officer Kanda, Masayuki Project Sponsor(s) GMR Infrastructure Limited Megawide Construction Corporation Description The Project involves the expansion of passenger terminals at Mactan Cebu International Airport (MCIA) (the Project), a priority PPP project of the government. This airport is the second largest airport in the Philippines and serves as the southern hub of the air transportation system in the country. MCIA is located on Mactan Island, Cebu Province, Central Visayas region. The components of the Project include (i) construction of a new passenger terminal; (ii) rehabilitation of the existing terminal; (iii) construction of an apron for the new passenger terminal; and (iv) operation, maintenance; and management of the new and old passenger terminals. Upon completion, the project will increase the capacity of the airport to 8 million passengers annually. -

Narratives of Patagonian Exploration Mark W

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research Fall 8-2001 Going to nowhere : narratives of Patagonian exploration Mark W. Bell Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bell, Mark W., "Going to nowhere : narratives of Patagonian exploration" (2001). Master's Theses. Paper 1143. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Since its discovery on Magellan's circumnavigation, Patagonia has been treated differently than any other region in the world. Effectively, Patagonia has been left empty or vacated by the North. But this emptiness and blankness have compulsively attracted curious travel writers who have filled the emptiness of Patagonia with self-reflexive projections. From Charles Darwin and W.H. Hudson to Bruce Chatwin and Paul Theroux, Northern commentators have found in Patagonia a landscape that accommodates their desire for self-reflexivity and self-consciousness. Thus, Patagonia has been simultaneously filled and evacuated by the Northern mind. As a result, Patagonia has become increasingly about the self and less about the physical place to the point where Patagonia as a concept has been abstracted and made into a trope or condition. This paper examines the history of Patagonia in literature in English and analyzes how Patagonia has evolved into its modem signification. I certify that I have read this thesis and find that, in scope and quality, it satisfies the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. -

Cebu-Ebook.Pdf

About Cebu .........................................................................................................................................2 Sinulog festival....................................................................................................................................3 Cebu Facts and Figures .....................................................................................................................4 Cebu Province Towns & Municipalities...........................................................................................5 Sites About Cebu and Cebu City ......................................................................................................6 Cebu Island, Malapascus, Moalboal Dive Sites...............................................................................8 Cebu City Hotels...............................................................................................................................10 Lapu Lapu Hotels.............................................................................................................................13 Mactan Island Hotels and Resorts..................................................................................................14 Safety Travel Tips ............................................................................................................................16 Cebu City ( Digital pdf Map ) .........................................................................................................17 Mactan Island ( Digital -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Language, Tagalog Regionalism, and Filipino Nationalism: How a Language-Centered Tagalog Regionalism Helped to Develop a Philippine Nationalism Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/69j3t8mk Author Porter, Christopher James Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Language, Tagalog Regionalism, and Filipino Nationalism: How a Language-Centered Tagalog Regionalism Helped to Develop a Philippine Nationalism A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Southeast Asian Studies by Christopher James Porter June 2017 Thesis Committee: Dr. Hendrik Maier, Chairperson Dr. Sarita See Dr. David Biggs Copyright by Christopher James Porter 2017 The Thesis of Christopher James Porter is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Table of Contents: Introduction………………………………………………….. 1-4 Part I: Filipino Nationalism Introduction…………………………………………… 5-8 Spanish Period………………………………………… 9-21 American Period……………………………………… 21-28 1941 to Present……………………………………….. 28-32 Part II: Language Introduction…………………………………………… 34-36 Spanish Period……………………………………….... 36-39 American Period………………………………………. 39-43 1941 to Present………………………………………... 44-51 Part III: Formal Education Introduction…………………………………………… 52-53 Spanish Period………………………………………… 53-55 American Period………………………………………. 55-59 1941 to 2009………………………………………….. 59-63 A New Language Policy……………………………… 64-68 Conclusion……………………………………………………. 69-72 Epilogue………………………………………………………. 73-74 Bibliography………………………………………………….. 75-79 iv INTRODUCTION: The nation-state of the Philippines is comprised of thousands of islands and over a hundred distinct languages, as well as over a thousand dialects of those languages. The archipelago has more than a dozen regional languages, which are recognized as the lingua franca of these different regions.