Opera As Visual, Vocal Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Piano; Trio for Violin, Horn & Piano) Eric Huebner (Piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (Violin); Adam Unsworth (Horn) New Focus Recordings, Fcr 269, 2020

Désordre (Etudes pour Piano; Trio for violin, horn & piano) Eric Huebner (piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (violin); Adam Unsworth (horn) New focus Recordings, fcr 269, 2020 Kodály & Ligeti: Cello Works Hellen Weiß (Violin); Gabriel Schwabe (Violoncello) Naxos, NX 4202, 2020 Ligeti – Concertos (Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Chamber Concerto for 13 instrumentalists, Melodien) Joonas Ahonen (piano); Christian Poltéra (violoncello); BIT20 Ensemble; Baldur Brönnimann (conductor) BIS-2209 SACD, 2016 LIGETI – Les Siècles Live : Six Bagatelles, Kammerkonzert, Dix pièces pour quintette à vent Les Siècles; François-Xavier Roth (conductor) Musicales Actes Sud, 2016 musica viva vol. 22: Ligeti · Murail · Benjamin (Lontano) Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano); Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; George Benjamin, (conductor) NEOS, 11422, 2016 Shai Wosner: Haydn · Ligeti, Concertos & Capriccios (Capriccios Nos. 1 and 2) Shai Wosner (piano); Danish National Symphony Orchestra; Nicolas Collon (conductor) Onyx Classics, ONYX4174, 2016 Bartók | Ligeti, Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Concerto for violin and orchestra Hidéki Nagano (piano); Pierre Strauch (violoncello); Jeanne-Marie Conquer (violin); Ensemble intercontemporain; Matthias Pintscher (conductor) Alpha, 217, 2015 Chorwerk (Négy Lakodalmi Tánc; Nonsense Madrigals; Lux æterna) Noël Akchoté (electric guitar) Noël Akchoté Downloads, GLC-2, 2015 Rameau | Ligeti (Musica Ricercata) Cathy Krier (piano) Avi-Music – 8553308, 2014 Zürcher Bläserquintett: -

Constructing the Archive: an Annotated Catalogue of the Deon Van Der Walt

(De)constructing the archive: An annotated catalogue of the Deon van der Walt Collection in the NMMU Library Frederick Jacobus Buys January 2014 Submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Master of Music (Performing Arts) at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Supervisor: Prof Zelda Potgieter TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DECLARATION i ABSTRACT ii OPSOMMING iii KEY WORDS iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION TO THIS STUDY 1 1. Aim of the research 1 2. Context & Rationale 2 3. Outlay of Chapters 4 CHAPTER 2 - (DE)CONSTRUCTING THE ARCHIVE: A BRIEF LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CHAPTER 3 - DEON VAN DER WALT: A LIFE CUT SHORT 9 CHAPTER 4 - THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION: AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE 12 CHAPTER 5 - CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 18 1. The current state of the Deon van der Walt Collection 18 2. Suggestions and recommendations for the future of the Deon van der Walt Collection 21 SOURCES 24 APPENDIX A PERFORMANCE AND RECORDING LIST 29 APPEDIX B ANNOTED CATALOGUE OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION 41 APPENDIX C NELSON MANDELA METROPOLITAN UNIVERSTITY LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SERVICES (NMMU LIS) - CIRCULATION OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT (DVW) COLLECTION (DONATION) 280 APPENDIX D PAPER DELIVERED BY ZELDA POTGIETER AT THE OFFICIAL OPENING OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION, SOUTH CAMPUS LIBRARY, NMMU, ON 20 SEPTEMBER 2007 282 i DECLARATION I, Frederick Jacobus Buys (student no. 211267325), hereby declare that this treatise, in partial fulfilment for the degree M.Mus (Performing Arts), is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment or completion of any postgraduate qualification to another University or for another qualification. -

To Download the Full Archive

Complete Concerts and Recording Sessions Brighton Festival Chorus 27 Apr 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Belshazzar's Feast Walton William Walton Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Baritone Thomas Hemsley 11 May 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Kyrie in D minor, K 341 Mozart Colin Davis BBC Symphony Orchestra 27 Oct 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Budavari Te Deum Kodály Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Sarah Walker Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Brian Kay 23 Feb 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Symphony No. 9 in D minor, op.125 Beethoven Herbert Menges Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Elizabeth Harwood Mezzo-Soprano Barbara Robotham Tenor Kenneth MacDonald Bass Raimund Herincx 09 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in D Dvorák Václav Smetáček Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Valerie Baulard Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 11 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Liebeslieder-Walzer Brahms Laszlo Heltay Piano Courtney Kenny Piano Roy Langridge 25 Jan 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Requiem Fauré Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Maureen Keetch Baritone Robert Bateman Organ Roy Langridge 09 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in B Minor Bach Karl Richter English Chamber Orchestra Soprano Ann Pashley Mezzo-Soprano Meriel Dickinson Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Stafford Dean Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 1 Brighton Festival Chorus 17 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra in C minor Beethoven Symphony No. -

Centre D'art Santa Mònica, Barcelona) Dedicated to Pere Formiguera (Barcelona, 1952

224 CATALAN REVIEW Finally, l would like to note the exhibition Cmnos (Centre d'Art Santa Mònica, Barcelona) dedicated to Pere Formiguera (Barcelona, 1952). This exhibition focused on photographs taken by him of some thirty diHerent people at different stages during their life showing how they changed du ring a period of ten years (from 1991-2000). Those selected were of two adults and two children who are shown growing older through some 600 photographs. Valencia also oHered exhibitions of great interest. Above all, l would like to highlight the retrospective Ramon Goya, el pintor de las ciutats (IVAM, Valencia), and the avant-garde artist Antonio Ballester (Valencia, 19IO) (IVAM). l should not forget to mention two other exhibicions also at the IVAM: Pierre Alechinsky, the Belgian expressionist and founder member of the group Cobra, and the other, Roy Lichtenstein. In contrast, in Perpignan (Palau de Congressos Georges Pompidou), there was an important retrospective Aristides Maillol, whose sculptures were on show offering examples from all his periods, themes, formats and techniques used by this sculptor. ANNA BUTÍ (Translated by Roland Pearson) MUSIC In the area of symphonic and instrumental concerts, the prestigious Lorin Maazel conducted the London Philharmonic Orchestra in mid-July (1999) as part of the summer season of the Festival de Peralada. Moving on to the Fall season, at the end of October the Barcelona and National Catalonian Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Franz-Paul Decker with guest violinist Catherine Cho, interpreted a fairly surprising pro gram dedicated to Sir Edward EIgar (the emblematÏc representative of English Romantic Music) in the Auditori. -

Newsletter • Bulletin Fall 2000 L'automne

NATIONAL CAPITAL OPERA SOCIETY • SOCIETE D'OPERA DE LA CAPITALE NATIONALE Newsletter • Bulletin Fall 2000 L'Automne P.O. Box 8347, Main Terminal, Ottawa, Ontario K1G 3H8 • C.P. 8347, Succursale principale, Ottawa, (Ontario) K1G 3H8 THE BRIAN LAW OPERA SCHOLARSHIP The Fifth Biennial Competition by Bobbi Cain A $2000 scholarship will be awarded to an aspir- Swerdfeger, will present a special recital. Mary ing young singer, aged 22 to 32 years, after a juried Ann is working in New York City in a variety of competition. The Brian Law Opera Scholarship roles, mostly of a light operatic nature, and we are was established in 1992 in honour of Brian Law, happy to welcome her glorious, yet dulcet tones to commemorate his dedication over a twenty- back to be with us in her hometown, Ottawa. five year period to young singers, to orchestral The competition evening begins at 7:30 P.M., and choral music, and to opera, both at the Na- and light refreshments will be available in the ad- tional Arts Centre and at l’Opera de Montreal. joining hall after the announcement of the winner. The upcoming scholarship competition A considerable amount of parking can be found will be held on Saturday, January 27, 2001 at the around the building, and buses run nearby. The First Unitarian Congregation, 30 Cleary Avenue. charge for the competition is $10.00, with tickets Up to six young finalists will perform a selection available at the door. Book this date now, and make of operatic arias, including one with recitative, sure you are with us for this exciting night. -

Inga Nielsen- Robert Hale

Inga Nielsen- Robert Hale Es war ein Interview mit Hindemissen: Diese ersten Erfolee ließen ihn noudund Golaud),insgesamt waren es Anfangs hatte es ein Podiumsgesprächschließlich doch an eine Ooernkamiere ca.40 Rollen. werdensollen. doch ich sah schließlich denken. Als er nach Ame-rika zurück. ein, daß beide Künstler zusanmen nur karn, nahm er erfolgreich an mehreren Und wie gelang dann der Sprung nach seltenZeit habenwürden.So einiste ich Wettbewerben teil und sewann meh- Europa?"Ich wußte, daß es zu diesem mich rnit Frau Nielsen, nur ihren-Mann rere heise, so z. B. als ii,lational Sin- Zeitpunlt für meine Opemkarrierebe- Robert Hale fiir diese Z€ituns zu inter- ger of the Year". Hale: "Das war sehr sonderswichtig war. in Europazu sin- viewen, mit ilr aber ftir späier ein Po- wichtig für mich, denn dadurch gewann gen. So arrangiertemein Agent ein diumsgesprächvorzusehen. ich Zutrauen rmd Sicherheit. Dies hat Vorsingen in Hamburg, Berlin und mir die Türen geöffuet, um Franldurt." Und bei einem Vorsineen Am vereinbartenTag für rmserTreffen Liederabende urd Konzerte zu sinsen." in Franldrt lemteer Inga Nielsenkin- nen."Sie war eineStunde vor mir beirn Repetieren, Ich hörte draußen zu InterYiew noch dem Welt\virt- unä war beeindruckt von dieser schafugipfel zum Opfer gefallen : schönen, klaren Stimrne. Dann (eine Polizei-Escofte begleitete -.. lernte ich sie persönlich kennen mich zul Hotel-Rezeption). und dachte zuerst, daß sie Ame- rikanerin ist - so gut sprach sie C Aber schließlich saßen wir dann englisch." - Zwei Jahre später doch alle drci zusamrnen,und weil warcn sie Yerheiratet. die Zeit noch reichte, konnte ich auchmit Frau Nielsen sprechen. -

Federals Making Brave Stand in Mazatlan City

( PRESS RUN ^ ■hi AVERAGE DAILY CIRCULATION TBS WBATHSR for the month of Febrcarjr, 1920 Vovtcast Ur a. S. WretMx Bareaa, 5,284 Mear Maeca Member of the Aadit Bareae of C o n n . State L ib r »ry -4> « P - _ , Tioeal flhower^ and slighGy wann> Ctrcoletlona ■i er tonight; Sunday showers fol> .... - ■ - ^ ■: I lowed by fair. VOL. XLIIL, NO. 135. (Classifled Advertising on Page 10) SOUTH MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, MARCH 23,1929. TWELVE PAGES PRICE THREE CENTS f ANNE’S PICTURE ADDED . HEARING ON TO LINDBERGH EXHIBIT. Working Upside Down Undersea St. Louis, Alarch 23.— A pic LAY PLANS FOR GANG’S GUNS ture of Miss Anne Spencer Mor row, fiancee of Col. Charles A. FEDERALS MAKING DIRT ROADS Lindbergh, will be added to the large and varied Lindbergh col THE DEFEAT OF AGAIN ROAR lection at the Jefferson Memorial here. m WEEK Miss Morrow who recently CONSOLJDATION BRAVE STAND IN viewed the many Lindbergh tro IN CHICAGO phies, readily agreed to add her % favorite photograph to the collec State Legislators E x p e c t tion. Eighth District Meeting Lines MAZATLAN CITY Trophies for the Flying Col One Dead, One Fatally onel continue to come in from all Stubborn Battle Whenj parts of the world. The ex Up Its Arguments Against hibit now fills the entire west Wounded as Machine Gun Subject is Brought Before; wing of the Jefferson Memorial. NOTE FROM MEXICO into city and I ■ <• AH New Charter Pro Sprays Street— Battle of the Committee. posals. Beer Runners. DESCRIBES r e v o l t! ^ DRY CUTTER SINKS ___ Forces Under Gen. -

02 Istituz Rnd:V

la rondine commedia lirica in tre atti libretto di Giuseppe Adami musica di Giacomo Puccini Teatro La Fenice sabato 26 gennaio 2008 ore 19.00 turni A1-A2 domenica 27 gennaio 2008 ore 15.30 turni B1-B2 martedì 29 gennaio 2008 ore 19.00 turni D1-D2 mercoledì 30 gennaio 2008 ore 17.00 turni C1-C2 giovedì 31 gennaio 2008 ore 19.00 turni E1-E2 domenica 3 febbraio 2008 ore 17.00 fuori abbonamento martedì 5 febbraio 2008 ore 19.00 fuori abbonamento La Fenice prima dell’Opera 2008 1 Arturo Rietti (1863-1943), Giacomo Puccini (1906). Milano, Museo Teatrale alla Scala. La Fenice prima dell’Opera 2008 1 Sommario 5 La locandina 7 «E il passato sembrami dileguar»… di Michele Girardi 13 Giovanni Guanti «Vedranno i posteri che Bijou!» 27 Daniela Goldin Folena La rondine: un libretto inutile? 45 Giacomo Puccini Sogno d’or (1912) 47 La rondine: libretto e guida all’opera a cura di Michele Girardi 101 La rondine: in breve a cura di Maria Giovanna Miggiani 103 Argomento – Argument – Synopsis – Handlung 111 Michela Niccolai Bibliografia 121 Online: Voli pindarici a cura di Roberto Campanella 133 Dall’archivio storico del Teatro La Fenice La rondine, capolavoro beneaugurante a cura di Franco Rossi Locandina per la prima rappresentazione della Rondine al Teatro La Fenice di Venezia. Nei ruoli principali can- tavano: Linda Canneti (Magda), Alba Damonte (Lisette), Manfredi Polverosi (Ruggero), Nello Palai (Prunier). Archivio storico del Teatro La Fenice. la rondine commedia lirica in tre atti libretto di Giuseppe Adami musica di Giacomo Puccini versione 1917 -

Inga Nielsen Live & Studio Recordings Voices 1952-2007

Inga Nielsen Live & Studio Recordings Voices 1952-2007 CHAN 10444(2) CCHANHAN 1104230423 BBookletooklet CCover.inddover.indd 1 11/8/07/8/07 110:24:250:24:25 Kaiserin (‘Die Frau ohne Schatten’) at La Scala, Milan Photo: Andrea Tamoni Inga Nielsen Voices Live & Studio Recordings 1952-2007 2 CCHANHAN 110444(2)0444(2) BBooklet.inddooklet.indd 22-Sec1:3-Sec1:3 11/8/07/8/07 110:19:360:19:36 CD 1 Opera, Oratorio 1 George Frideric Handel ATHALIA Athalia: ‘My Vengeance’ 4:29 6 Charles Gounod FAUST Marguerite: ‘O Dieu! que de bijoux!’ 4:54 Conductor: Christopher Hogwood Conductor: Eugene Kohn Recorded live 11 March1993, Danish Radio Concert Hall, Copenhagen Recorded live 7 August 1993, ‘Parken’- Stadium, Copenhagen 2 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart IDOMENEO Elettra: ‘Tutte nel cor vi sento’ 5:18 7 Jules Massenet MANON Manon - Des Grieux: ‘Toi! Vous! Oui… c’est moi!’ 8:34 Conductor: Gustav Kuhn Des Grieux: Plácido Domingo Recorded live 5 December 1991, Tivoli Concert Hall, Copenhagen Conductor: Eugene Kohn Recorded live 7 August 1993, ‘Parken’- Stadium, Copenhagen 3 Ludwig van Beethoven FIDELIO Leonore: ‘Abscheulicher! Wo eilst du hin?’ 7:28 Conductor: Gerd Albrecht 8 Richard Wagner TANNHÄUSER Elisabeth: ‘Dich, teure Halle’ 5:07 Recorded live 11 March 1999, The Royal Theatre, Copenhagen Conductor: Michael Schønwandt Recorded live 14 August 1997, Tivoli Concert Hall, Copenhagen 4 Gaetano Donizetti LUCIA DI LAMMERMOOR Lucia: ‘Il dolce suono’ 16:13 Enrico: Alberto Noli, Raimondo: Christian Christiansen, Normanno: Stig Fogh Andersen 9 Richard Strauss DIE FRAU -

Celebrate Beethoven Catalogue Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770–1827)

CELEBRATE BEETHOVEN CATALOGUE LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770–1827) Born in Bonn in 1770, the eldest son of a singer in the Kapelle of the Archbishop-Elector of Cologne and grandson of the Archbishop’s Kapellmeister, Beethoven moved in 1792 to Vienna. There he had some lessons from Haydn and others, quickly establishing himself as a remarkable keyboard player and original composer. By 1815 increasing deafness had made public performance impossible and accentuated existing eccentricities of character, patiently tolerated by a series of rich patrons and his royal pupil the Archduke Rudolph. Beethoven did much to enlarge the possibilities of music and widen the horizons of later generations of composers. To his contemporaries he was sometimes a controversial figure, making heavy demands on listeners by both the length and the complexity of his writing, as he explored new fields of music. Beethoven’s monumental contribution to Western classical music is celebrated here in this definitive collection marking the 250th anniversary of the composer’s birth. ThisCELEBRATE BEETHOVEN catalogue contains an impressive collection of works by this master composer across the Naxos Music Group labels. Contents ORCHESTRAL .......................................................................................................................... 3 CONCERTOS ........................................................................................................................ 13 KEYBOARD ........................................................................................................................... -

Xxiv Edizione Corsi Internazionali Di Perfezionamento Musicale

QUOTE DI PARTECIPAZIONE - FEES 1 - 7 AGOSTO Città di REGOLAMENTO REGULATIONS Quota di iscrizione - Enrolment fee: Janne Thomson Flauto - Flute Cividale Possono partecipare ai corsi allievi di qualsiasi nazionalità ed età. Courses are open to any students. There are no age or nationality Per tutti i corsi - All courses and auditors 60 8 - 14 AGOSTO Tutti i corsi prevedono la presenza di allievi effettivi e uditori. restrictions. Students can apply either as uditors or as active del Friuli La domanda di iscrizione dovrà essere indirizzata all’Ufficio cultu- players. David Cohen nd Quota di frequenza - Attendance fee: Violoncello - Cello ra del Comune di Cividale del Friuli - Piazza Paolo Diacono, 10 Application forms must arrive by 22 July 2011 (postmark valid) - 33043 - Cividale del Friuli (UD) - Italia - dove dovrà pervenire and have to be addressed to: Ufficio cultura del Comune di Clarinetto, flauto, pianoforte, contrabbasso, violino, viola, violoncello 1 - 7 AGOSTO entro il 22 luglio 2011 (fa fede la data del timbro postale). È possi- Cividale del Friuli - Piazza Paolo Diacono, 10 - 33043 - Cividale (M° Mitchell e Rowland)) Priya Mitchell Violino - Violin bile anche l’iscrizione on line, seguendo le indicazioni contenute del Friuli (UD) - Italy. Partecipants can enroll also via Internet Flute, piano, double-bass, viola, cello, violin (M° Mitchell e Rowland) € 300 ASSESSORATO nel sito www.perfezionamentomusicale.net. (www.perfezionamentomusicale.net). 8 - 14 AGOSTO ALLA CULTURA Unitamente alla domanda di iscrizione, ogni singolo candidato dovrà Please enclose the following documents: Mandolino e fisarmonica € Daniel Rowland allegare: • enrolment fee receipt (not refundable). The fee must be paid by Mandolin and accordeon 200 Violino - Violin Associazione Musicale • la ricevuta del versamento unicamente della quota di iscrizione (non money transfer to: Banca di Cividale s.p.a. -

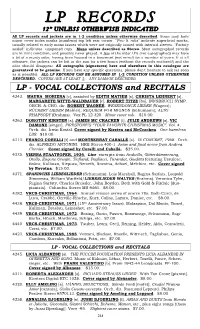

LP RECORDS 12” UNLESS OTHERWISE INDICATED All LP Records and Jackets Are in 1-2 Condition Unless Otherwise Described

LP RECORDS 12” UNLESS OTHERWISE INDICATED All LP records and jackets are in 1-2 condition unless otherwise described. Some may have minor cover index marks (numbers) top left rear corner. "Few lt. rubs" indicate superficial marks, usually related to early mono issues which were not originally issued with internal sleeves. "Factory sealed" indicates unopened copy. Mono unless described as Stereo. Most autographed records are in mint condition, and possibly never played. A few of the older LPs (not autographed) may have a bit of a musty odor, having been housed in a basement (not mine!) for a number of years. If at all offensive, the jackets can be left in the sun for a few hours (without the records enclosed!) and the odor should disappear. All autographs (signatures) here and elsewhere in this catalogue are guaranteed to be genuine. If you have any specific questions, please don’t hesitate to ask (as soon as is possible). ALL LP RECORDS CAN BE ASSUMED IN 1-2 CONDITION UNLESS OTHERWISE DESCRIBED. COVERS ARE AT LEAST 2. ANY DAMAGE DESCRIBED. LP - VOCAL COLLECTIONS and RECITALS 4243. MAURA MORIERA [c], assisted by EDITH MATHIS [s], CHRISTA LEHNERT [s], MARGARETE WITTE-WALDBAUER [c], ROBERT TITZE [bs], INNSBRUCH SYMP. ORCH. & CHO. dir. ROBERT WAGNER. WESENDONCK LIEDER (Wagner); RÜCKERT LIEDER (Mahler); REQUIEM FOR MIGNON (Schumann); ALTO RHAPSODY (Brahms). Vox PL 12.320. Minor cover rub. $10.00. 4263. DOROTHY KIRSTEN [s], JAMES MC CRACKEN [t], JULIE ANDREWS [s], VIC DAMONE [singer]. FIRESTONE’S “YOUR FAVORITE CHRISTMAS MUSIC”. Vol. 4. Orch. dir. Irwin Kostal. Cover signed by Kirsten and McCracken.