Excellence and Equity for All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Tech Apprentice Program Summary

2016 TECH APPRENTICE PROGRAM SUMMARY I think many people would be surprised at the level the summer interns function at in the workplace“ and what they are able to accomplish in such a short period of time. Our Chief Information Security Officer was ecstatic with their contributions during their internship. I would have thought I was listening to college interns present at the closing ceremony.” Jim Noga, Chief Information Officer, Partners HealthCare WHAT IS TECH APPRENTICE? Tech Apprentice is a six-week, paid summer internship program for tech-savvy Boston public high school students who want to work at local companies. These talented students are considering pursuing IT majors in college, and they need a work-based experience to help them understand the options available to them in the high-tech arena. $260,000 111 44 in wages paid to students students worked on IT employers participated by this summer and tech projects hiring and mentoring students 2016 TECH APPRENTICE PLACEMENTS STUDENT HIGH SCHOOL SUMMER EMPLOYER Andrew Reilly Boston Latin School America’s Test Kitchen Mccain Boonma John D. O’Bryant High School Autodesk Anthony Clark Excel High School Boston Financial Data Services Judress Sylvestrte Boston International High School Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Dominic Marcuse Mary Lyon High School Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Donovan LaMonica Boston Latin Academy Boston College Paul Joseph Boston Latin School Boston College Christian Franco East Boston High School Boston College Johanna Paris Jeremiah E. Burke High School Boston College Kenneth James Urban Science Academy Boston College Lukas Metlicka Boston Latin School Boston Luxury Properties Caiying Shen Boston Latin School Boston Properties Leylanah Mitchell Boston Latin Academy Castle Inc. -

Ocm08580879-1895.Pdf

LMisJaciue i f add. A SOUVENIR OF |fl as sac hit setts S^jjislattfrs l8 95 VOLUME IV. (Issued A nnually) A. M. BRIDGMAN BROCKTON, MASS. Copyrighted 1X95, by A. M. BRIDGMAN. \ GEO. H. ELLIS, PRINTER, 141 FRANKLIN STREET, BOST PHOTOGRAPHS FROM NOTMAN, PARK STREET HALFTONES FROM HUB ENGRAVING CO PREFACE. HP HE "Souvenir" of 1895 is the first to contain recoras of men who sat in the * State House Extension to make and unmake laws tor the state. It was a Legislature remarkable for containing the largest proportion of members from one political party ever known. The House contained 194 Republicans and 46 Democrats, while in the Senate there were only four Democrats to 36 Republicans. There were not enough even of the former to secure a roll call. And yet there was no unusual partisan legislation attempted. The majority always passes more or less legislation against the protest of the minority. The business of the session, although of greater volume than ever, was completed decently and in order and prorogation reached at the unusually early date of 1S95 was also remarkable for June 5, or the earliest since 1SS8. The session of the unusual number of deaths among its members. One Senator and two Representatives elect died without taking the oath of office, while two died after having served several weeks, and one on the very morning of the day the Legislature was prorogued. This "Souvenir" contains the portrait of every "Legislator" of the state, whether in Senate or House or Congress, as well as all members of the Executive Department. -

Excellence and Equity for All

Excellence and equity for all Unlocking opportunities for off-track youth in Boston Public Schools May 2018 By EY-Parthenon Education practice Ernst & Young LLP Excellence and equity for all This report (the Report) has been prepared by Ernst & Young LLP (EY US) for the purpose of assisting the Barr Foundation and Boston Public Schools. At the request of the Barr Foundation and Boston Public Schools, the report and its findings are intended for the benefit of the general public of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The nature and scope of our services were determined solely by the agreement between EY US, the Barr Foundation, and Boston Public Schools (the Agreement). Our procedures were limited to those described in the Agreement. Other persons who read this Report, who are not a party to the Agreement, do so at their own risk and are not entitled to rely on it for any purpose. EY US assumes no duty, obligation or responsibility whatsoever to any other parties that may obtain access to the Report. The services performed were advisory in nature. While EY US’s work in connection with this Report was performed under the standards of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), EY US did not render an assurance report or opinion under the Agreement, nor did its services constitute an audit, review, examination, forecast, projection or any other form of attestation as those terms are defined by the AICPA. None of the services provided constituted any legal opinion or advice. This Report is not being issued in connection with any issuance of debt or other financing transaction, and it may not be quoted in connection with the purchase or sale of any securities. -

S a School Ar Approach Rchives in H N Action: : a Practi Ice-Based D

School Archives in Action: A Practiice-Based Research Approach SARAH A. BUCHANAN The Meadows School, Las Vegas, Nevada Abstract: School archives consist of documents, artifacts,, and ephemera such as artwork and uniforms which form the foundation for understanding and constructing an individual school's history annd broader educational memory. Successful school archives have implemented research recommendations which have established the archival value of preserving these matterials, and their utility in support of community identity and service-learning. This paper surveys the development of school archives within their innstitutions and reports on continuing professional development activities worldwide for school archivists. The concept of practice-based research is applied in order to identify archival programs and examine specific uses for the hiistorical materials found in school archives. Introduction While archival materials have been housed in schools for generations, their visibility has increased in recent years as scholarly cultural and historical research has shifted in visible ways from the study of bureaucratic and organizationaal records to tthe study of the daily lives and everyday activities of citizens. The primary sources for such cultural studies increasingly derive from local communities, schools, and family archives.1 Public and nonpublic schools in the United States have collected materials since their rapid establishment nationwide in the nineteenth century. When recognizing their founding through a centennial celebration or related anniversary, many school administrators today have chosen to devote renewed attention to their heritage by establishing and supporting an archival program. This practice-based research surveys the development of school archives and is contextualized by a school archives literature review and professsional analysis. -

OFFICIAL MINUTES of the SCHOOL COMMITTEE BUDGET HEARING and MEETING March 16, 2016

OFFICIAL MINUTES OF THE SCHOOL COMMITTEE BUDGET HEARING AND MEETING March 16, 2016 The Boston School Committee held a budget hearing and meeting on March 16, 2016 at 5 p.m. at the Bruce C. Bolling Municipal Building, 2300 Washington Street, School Committee chamber, Roxbury, Massachusetts. For more information about any of the items listed below, visit www.bostonpublicschools.org, email [email protected] or call the Boston School Committee Office at (617) 635-9014. ATTENDANCE School Committee Members Present: Chairperson Michael O’Neill; Vice-Chair Dr. Hardin Coleman; Michael Loconto; Alexandra Oliver-Dávila; Jeri Robinson; Regina Robinson; Dr. Miren Uriarte; and student representative Savina Tapia. School Committee Members Absent: None. DOCUMENTS PRESENTED Grant for Approval: Special Education Program Improvement Grant (Fund Code 274) - $173, 784. International Travel Request: Boston Latin School - Canada, May 27-30, 2016 International Travel Request: The Muriel Snowden International School at Copley – France and Spain, April 13-23, 2016. FY2016 Supplemental Appropriation Request: United Steelworkers of America, Local 8751 (School Bus Drivers) - $2,783,841. Letter from Early Education Center and Early Learning Center School Leaders to EEC and ELC Communities, dated March 16, 2016 FY17 Budget Proposal Updating School Year 2017 and 2018 Calendars School Committee Budget Hearing and Meeting Bruce C. Bolling Municipal Building School Committee Chamber March 16, 2016 The English High School Chapter 74 Admissions Policy CALL TO ORDER Mr. O’Neill called the budget hearing to order. FISCAL YEAR 2017 BUDGET HEARING Seventy-five people testified regarding the Superintendent’s FY17 budget recommendation. CALL TO ORDER Following a brief recess, Mr. -

For Families and Students What's Inside

ENGLISH BOSTON To Families and Students: This publication contains Public Schools important information. Please read it. Arlington Medford Then, remove and sign the Parent and Focus on Children Revere Everett Student Agreement in the center of the Chelsea ! Belmont Bradley book and return the agreement to your Somerville ! Guild school. BOSTON Cambridge Charlestown Thank you. Umana !East Boston HS Edwards ! Academy MS ! Charlestown HS ! Public Schools ! !! PJ Kennedy Warren/ ! O'Donnell Prescott K-8 Harvard/ ! Kent Otis Focus on Children Alighieri ! Montessori ! East Boston EEC Eliot K-8 ! ! McKay K-8 Watertown (5-8) ! Adams! Eliot K-8 E. Boston Gardner K-8 (K1-4) ! Allston-Brighton Lyon Another 2015–2016 (9-12) Course to Jackson/Mann K-8 Quincy ! College ! Snowden Lyon (K-8)! Boston Green!! Horace Mann K-12 ! Upper Academy ! McKinley MS Boston Arts HS (6-12) !BATA ! Academy ! !Quincy Lower (K-5) ! Brighton HS ! Guide to the Edison Winship ! McKinley S. End K-8 McKinley Kennedy !! ! Acad & K-5 Prep HS HCA (11-12) Carter S. Boston Baldwin ELPA ! ! ! Center ! Blackstone Condon K-8 Fenway-Kenmore Hurley! Boston Latin ! ! Boston Public Schools School 7-12 K-8 S. End Tobin !Tynan Perry ! UP Academy Boston ! ! K-8 Madison Park HS ! K-8 Kennedy ! ! ! ! Excel HS HCA (9-10) ! Newton ! O'Bryant ! Orchard Gardens K-8 Perkins Fenway Timilty 7-12 HS MS ! West Zone ELC ! ! BDEA ! Mason for Families and Students Henningan K-8 Hale Higginson/ Dudley St ! Clap JF Kennedy ! ! !Lewis K-8 NCS ! Higginson Boston Latin Russell McCormack MS Brookline Curley K-8!! Mendell (K-2)! Academy ! Winthrop !! ! ! ! N. -

Hms Medscience Survey Highlights Brochure

HMS MEDSCIENCE SURVEY HIGHLIGHTS BROCHURE JULIE JOYAL, RN, M.ED, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR NANCY ORIOL, MD, PRESIDENT & CO-FOUNDER LIVIA RIZZO, PROGRAM DIRECTOR HMS MEDscience is a high school STEM education initiative inspiring students to think without limits and engaging them in science through hands-on experiences. Our mission is to bridge the inspiration gap in STEM education by providing students with opportunities in science that enhance the necessary 21st century skills for success in academic and career settings. The purpose of the survey is to measure student outcomes. Data was collected from 223 students participating in the HMS MEDscience program Fall Semester 2019. Core findings include: LEARNING ENVIRONMENT • 99% of our student participants agree or strongly agree that the pedagogy of the MEDscience program helped them retain and learn the material better. • 96% agree or strongly agree that the cases with the simulator deepened their understanding of biology concepts. BIOLOGY CONTENT • Before the program, only 38% of our participants understood causes and treatments for heart disease. After, 95% reported that they understand the causes and treatments of heart disease. • Students saw similar growths in regards to the understanding the physiological mechanism of an asthma attack and inhaler treatment, and how insulin works in your body in correspondence to diabetes. SELF-EFFICACY, LEADERSHIP & TEAMWORK • 91% report that after participating in HMS MEDscience, he/she is more confident in sharing their ideas in class, even if they might be wrong • 98% of our student participants agree or strongly agree that after participating in HMS MEDscience he/she is comfortable working in teams in emergency situations. -

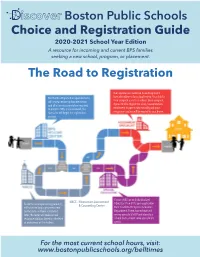

Choice and Registration Guide 2020-2021 School Year Edition a Resource for Incoming and Current BPS Families Seeking a New School, Program, Or Placement

Boston Public Schools Choice and Registration Guide 2020-2021 School Year Edition A resource for incoming and current BPS families seeking a new school, program, or placement. The Road to Registration Your application travels on to an Assignment Meet with a Registration Specialist who Specialist where it has a final review. Your child is will review residency documentation then assigned a seat in a school. Once assigned, and all other documentation required if your child is eligible for a bus, transportation to enroll in BPS; once reviewed, the enrollment happens automatically and your Specialist will begin the registration assignment notice will be mailed to your home. process. If your child has an Individualized NACC: Newcomers Assessment Students, accompanied by parent(s), Education Plan (IEP), your application & Counseling Center will take the language assessment then travels to the Special Education on the date and time scheduled. Department. There, trained staff will After, the tester will make school review your child’s IEP and identify a recommendations based on the level school that can best serve your child’s of proficiency of the student. needs. For the most current school hours, visit: www.bostonpublicschools.org/belltimes Introduction IMPORTANT DATES Start of End of Priority Priority Assignment Registration Registration Notifications Students January January March entering grades K0, K1, 6, 7, or 9. 6 31 31 Students February April May entering K2 & ALL OTHER grades. 10 3 29 oston Public Schools offer academic, social-emotional, cultural, and extracurricular programs that meet the diverse needs of all families across the city. From pre- Bkindergarten through high school, our schools strive to develop in every learner the knowledge, skills, and character to excel in college, career, and life. -

Greater Boston Youth Program Guide

Greater Boston Youth Program Guide Compiled by The Steppingstone Foundation Greater Boston Youth Program Guide, ©, 2013, The Steppingstone Foundation®, Inc. The Admission Department at Steppingstone is pleased to provide you with a guide to Greater Boston Youth Programs. In this booklet you will find a list of organizations that offer opportunities for personal and academic enrichment for your child. The resources listed in this guide are by no means exhaustive. There are many people and organizations that can assist you directly with your quest for an enrichment program. See the Further Resources listing for additional programs and information. It is our hope and intention that this booklet serves as a jumpstart to your enrichment program search. Please note that the brief descriptions of these opportunities were taken directly or excerpted from organizations’ collateral materials. More detailed information can be found on the web site addresses noted in each section. Please call the organizations directly for clarification, specific deadlines, and information on eligibility. Good luck! Table of Contents 1. Pathways to College Balfour Academy (students in 6th grade can apply: helps through high school) The Bottom Line (students in 11th and 12th grade: must live in certain areas) Breakthrough Cambridge (students in 6th grade: helps through high school) (must live in area) College Bound Dorchester (all ages) Freedom House PUSH (students in 10-12th grade and freshman to senior year in college) Higher Education Resource Centers (students in middle school and then 10th grade) Talented and Gifted (TAG) Hispanic Programs (students in 6th-12th grade) Trinity Education for Excellence Program (students in 6th grade: helps through high school) Upward Bound (Math, Science, Umass, etc) (students in high school) Urban Scholars Program (students in 6th-10th grade: must be part of certain schools) 2. -

Read the Final BPS District Turnaround Plan

Boston Public Schools District Turnaround Plan June 29, 2010 INTRODUCTION In January 2010, the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education identified 35 underperforming schools across the Commonwealth, which they refer to as Level 4 schools. Twelve of those schools are in the Boston Public Schools, and each requires immediate and intensive intervention. Each of these schools is eligible to compete for federal School Improvement Grant (SIG) funding. School eligibility for SIG funds hinges on a school district’s implementation of one of four federal intervention models at each school. Those four federal intervention models are the transformational model, turnaround model, restart model, and closure (see appendix 1). Regulations governing the four federal intervention models dictate that in districts with more than 9 identified underperforming (Level 4) schools, the transformational model cannot be used in more than half of those designated schools. Upon review of both quantitative and qualitative data, the Superintendent will use the intervention models at our Level 4 schools in the following way: • Agassiz Elementary School (Transformational) • Blackstone Elementary School (Turnaround) • Burke High School**1 • Dearborn Elementary (Transformational) • Dever Elementary (Turnaround) • Elihu Greenwood Elementary (Transformational) • English High School (Transformational) • Harbor Pilot Middle School (Turnaround) • Holland Elementary School (Transformational) • John F. Kennedy Elementary School (Transformational) • Orchard Garden K-8 Pilot School (Turnaround) • Trotter Elementary School (Turnaround) To turn each school around and put them on track for success within a three-year period, we propose a turnaround plan that builds on empirical research and field knowledge. Our analysis of what works to turn around schools revealed that seven (7) areas are vital to success. -

Official Minutes of the School Committee Meeting

OFFICIAL MINUTES OF THE SCHOOL COMMITTEE MEETING April 30, 2014 The Boston School Committee held a meeting at 5 p.m. on April 30, 2014 at the Edward Winter Chamber, 26 Court Street, Boston, Massachusetts. For more information about any of the items listed below, visit www.bostonpublicschools.org, email [email protected] or call the Boston School Committee Office at (617) 635-9014. DOCUMENTS PRESENTED Minutes of the April 9, 2014 School Committee Meeting Grants for Approval Totaling $307,398 o Academic Support Services, Allocation Grant Program, Summer 2014 - $198,000 o Sustainable Materials Recovery Program Municipal Grant - $15,000 o Teen Pregnancy Prevention: Partners for Youth Success Continuation - $3,380 o Title I, Part A - $91,018 Superintendent’s Memo: Interim Salary Payment Order for External Funds Boston School Committee’s Strategic Vision: Aspirational Goals and Priorities Boston Public Schools Superintendent of Schools Desired Characteristics (Draft) Report: Round 1 Results and the Home Based Assignment System Report: Update on Special Education Report: Introducing the BPS Office of Engagement ATTENDANCE PRIOR TO EXECUTIVE SESSION School Committee Members Present: Chairperson Michael O’Neill; Meg Campbell; Dr. Hardin Coleman; Rev. Dr. Gregory G. Groover; and Michael Loconto. School Committee Meeting Edward Winter Chamber April 30, 2014 School Committee Members Absent: Vice-Chairperson Claudio Martinez; Margaret McKenna (arrived during executive session); and student representative Ayomide Olumuyiwa. CALL TO ORDER Mr. O’Neill called the meeting to order and led the pledge of allegiance. EXECUTIVE SESSION On roll call, the Committee voted unanimously to adjourn to executive session to discuss strategy for collective bargaining. -

Boston Educator 06.06.Qxp

The Boston Educator, Spring 2004 SPRING 2003 ◆ Vol. 1, No. 1 Vol.3, No. 2 Autumn 2006 Mayor Thomas M. Menino, Super man left, and Interim Superintendent Contompasis answers schools’ call for interim leader Michael G. BY MEAGHAN CASEY Contompasis here to provide as smooth a transition as possible greet Everett With one foot out the door last spring, Michael and make it clear that the work will go on.” School third- G. Contompasis was drawn back in to extend his The smooth transition was evident on the first graders, from 41-year legacy in the Boston Public Schools. day of school, Sept. 7, when he and Mayor Thomas left, Lissa The former BPS chief operating officer, who was M. Menino did a tour of schools. Lopes, Khalilah to retire in June, was named interim superintendent Contompasis was approached by the School Evora, Jasmine upon Dr. Thomas W. Payzant’s retirement. Committee, the Mayor’s office, and colleagues to Castro, and “After 41 years at an active pace, it’s hard to delay his retirement and take on the added Anthony Alves believe I would’ve been able to settle into a rocking responsibilities. on the first day chair,” quipped Contompasis. “I don’t intend to sit The search committee that was appointed to of school. back and bide time or maintain the status quo. I’m See CONTOMPASIS Page 14 insidethe autumnedition Forensics class captures interest of CHS students SPACE SCHOOL BY CAITLIN BOWLER Horace Mann students visited by astronaut With students brushing for fingerprints, analyzing hair under microscopes, pouring footprints outside or Page 3 examining fibers under ultraviolet lights as they hone the skills of crime-scene analysis, forensic science classes at Charlestown High School are unlike any others — and students are hooked.