Ethnic Marked Names As a Reflection of United States Isolationist Attitudes in <I>Uncle &Dollar;Crooge</I> Comic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncle Scrooge and Liquidity Preference

Uncle Scrooge and Liquidity Preference In my childhood neighborhood on the Old Rock Island Road in East Wenatchee, most kids liked comic books. Batman, Spiderman, Flash Gordon, and of course Superman were always popular. I didn’t care much for the action heroes. I can only remember two comic book characters I liked. One was a fat little kid named Tubby in the comic Lu Lu. Tubby, Lu Lu and their friends had a very neat clubhouse. As a chunky little kid myself, I liked Tubby a lot. I guess I had a preference for housing at an early age as well. But my all-time favorite comic book character was Donald Duck’s uncle, Uncle Scrooge McDuck. I never liked Donald himself, a holdover from the cartoons at the Saturday matinee. I found his voice so irritating. Uncle Scrooge, however, to a budding six-year-old economist was sublime. Maybe you remember Uncle Scrooge and his castle with the money bin where he kept his billions of dollars of cash, mostly coin, that he pushed around with what we called in those days a bulldozer. I imitated my comic book hero by converting my weekly allowance and cash gifts to coin. I often dumped my total financial wealth onto my bed, and with cupped dozer-hands pushed it around a la Uncle Scrooge. Like Scrooge McDuck, I too was a harmless miser, not a malicious one like Dickens’ Scrooge. From an early age, I didn’t like to spend money. I think it had something to do with my first purchase. -

Walt Disneys Donald Duck: Scandal on the Epoch Express : Disney Masters Vol

WALT DISNEYS DONALD DUCK: SCANDAL ON THE EPOCH EXPRESS : DISNEY MASTERS VOL. 10 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mau Heymans | 192 pages | 14 Apr 2020 | FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS | 9781683962496 | English | United States Walt Disneys Donald Duck: Scandal on the Epoch Express : Disney Masters Vol. 10 PDF Book Donald Duck Adventures Disney. Donald Duck Coloring Book Whitman Disney Comics Special Donald Duck Of course, once again all the stories have been shot from crisp originals, then re-colored and printed to match, for the first time since their original release over 60 years ago, the colorful yet soft hues of the originals-and of course the book is rounded off with essays about Barks, the Ducks, and these specific stories by Barks experts from all over the world! Anthropomorphic animals Adventure. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. I love the Disney Masters series because we get treated to stories and illustrations from other great Duck comic creators besides the legendary Barks and Rosa. Donald Duck Beach Party Bas Heymans was born in in Veldhoven, Netherlands. Post was not sent - check your email addresses! Email required Address never made public. Published Nov by Fantagraphics. Notify me of new posts via email. Date This week Last week Past month 2 months 3 months 6 months 1 year 2 years Pre Pre Pre Pre Pre s s s s s s Search Advanced. Other books in the series. In this collection of comics stories, Donald battles master spies and his own Uncle Scrooge! There was a dinner meeting that took place in September that they both attended among some Disney comic greats from California and Italy. -

Dei Fumetti Disney Di Realizzazione Statunitense (1945-1960)

FRANCESCO SESTITO DA BALATRONE A GOLASECCA: SONDAGGI SULLE MODALITÀ DI TRADUZIONE IN ITALIANO di antroponimi e toponimi ‘minori’ DEI FUMETTI DISNEY DI REALIZZAZIONE STATUNITENSE (1945-1960) Abstract: Abstract: Research concerning onomastics in Disney comics in Italian has produced important results, but, while the names of main characters and places have been thoroughly dealt with, the onomastics of the minor realities of the Dis- ney universe, which was created in the USA and reached Italy in translation, are not equally well known. In this paper I analyze several stories written in the years 1945-1960 and Italian versions from different periods. The translation techniques vary somewhat: some retain the original English forms, some Italianize the original names, some create new anthroponyms or toponyms in a fairly free way. Keywords: Disney comics, minor characters, anthroponyms, toponyms, translations Il mondo del fumetto Disney comprende una sterminata produzione di storie – stimabili a più di 35.000 – realizzate in diversi paesi dal 1930 a oggi, offrendo numerosissimi spunti sui nomi propri, dei personaggi e dei luoghi, rappresentati nelle storie stesse.1 Gli studi sull’onomastica di- sneyana sono ormai numerosi benché tutti relativamente recenti:2 basti 1 Il sito Inducks (catalogo di opere e personaggi: https://inducks.org) censisce esattamente (no- vembre 2018) 35.081 storie ufficialmente pubblicate. A questo strumento in rete, ormai impre- scindibile, così come all’enciclopedia in rete Paperpedia (http://it.paperpedia.wikia.com), -

Disney Comics from Italy♦ © Francesco Stajano 1997-1999

Disney comics from Italy♦ © Francesco Stajano 1997-1999 http://i.am/filologo.disneyano/ A Roberto, amico e cugino So what exactly shall we look at? First of all, the Introduction fascinating “prehistory” (early Thirties) where a few pioneering publishers and creators established a Disney Most of us die-hard Disney fans are in love with those presence in Italy. Then a look at some of the authors, seen comics since our earliest childhood; indeed, many of us through their creations. Because comics are such an learnt to read from the words in Donald’s and Mickey’s obviously visual medium, the graphical artists tend to get balloons. Few of us, though, knew anything about the the lion’s share of the critics’ attention; to compensate for creators of these wonderful comics: they were all this, I have decided to concentrate on the people who calligraphically signed by that “Walt Disney” guy in the actually invent the stories, the script writers (though even first page so we confidently believed that, somewhere in thus I’ve had to miss out many good ones). This seems to America, a man by that name invented and drew each and be a more significant contribution to Disney comics every one of those different stories every week. As we studies since, after all, it will be much easier for you to grew up, the quantity (too many) and quality (too read a lot about the graphical artists somewhere else. And different) of the stories made us realise that this man of course, by discussing stories I will also necessarily could not be doing all this by himself; but still, we touch on the work of the artists anyway. -

Ebook Download Walt Disneys Uncle Scrooge: the Seven Cities of Gold

WALT DISNEYS UNCLE SCROOGE: THE SEVEN CITIES OF GOLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Carl Barks | 234 pages | 02 Nov 2014 | FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS | 9781606997956 | English | United States Walt Disneys Uncle Scrooge: The Seven Cities of Gold PDF Book Fantagraphics' second release in this series focuses on Carl Barks's other protagonist and perhaps greatest creation: Scrooge McDuck. IDW's issues of Uncle Scrooge use a dual-numbering system, which count both how many issues IDW itself has published and what number issue it is in total for instance, IDW first issue's was billed as " 1 ". Next, Huey, Dewey, and Louie try to figure out how to prevent a runaway train from crashing when no one will listen! Plus: the oddball inventions of the ever-eccentric Gyro Gearloose! Carl Barks delivers another superb collection of all-around cartooning brilliance. Issue ST No image available. Tweet Clean. This book has pages of story and art, each meticulously restored and newly colored, as well as insightful story notes by an international panel of Barks experts. My new safe is locked against any form of burglary! Add to cart. Sound familiar? Naturally, Scrooge wants to claim it as his own. This edit will also create new pages on Comic Vine for: Beware, you are proposing to add brand new pages to the wiki along with your edits. And after donning a virtual reality headset, Donald and the boys find themselves menaced by creatures on other worlds. We made holiday shopping easy: browse by interest, category, price or age in our bookseller curated gift guide. Written by Carl Barks. -

Under Exclusive License to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021 PC

INDEX1 A C Adaptation studies, 130, 190 Canon, 94, 146, 187, 188, 193, Adenauer, Konrad, 111, 123 194, 214 Adenauer Era, 105 Cochran, Russ, 164 Another Rainbow, 164, 176 Comics Code, 122 Comics collecting, 146, 161 Cultural diplomacy, 51, 55, 59, B 113, 116 Barks, Carl, 3, 43–44, 61, 62, 69, 185 Calgary Eye-Opener, 72, 156 D early life and career, 71 Dell Comics, 3, 5, 15, 30, 98, “The Good Duck Artist,” 67 123, 143 identifcation by fans, 99 De-Nazifcation, 6, 105 oil portraits, 72, 100, 165 Disney, Walt, 2, 38, 49, 53, 57, 59, retirement, 97 66, 69, 80, 143 Beagle Boys, 74, 135 Disney animated shorts Branding, 39, 56, 57, 66 The Band Concert, 40 Europe, 106 Commando Duck, 65, 121 Bray, J.R., 34 Der Fuehrer’s Face, 62 Col. Heeza Liar, 47 Donald and Pluto, 42 1 Note: Page numbers followed by ‘n’ refer to notes. © The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature 219 Switzerland AG 2021 P. C. Bryan, Creation, Translation, and Adaptation in Donald Duck Comics, Palgrave Fan Studies, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73636-1 220 INDEX Disney animated shorts (cont.) F Donald Gets Drafted, 61 Fan studies, 26, 160 Don Donald, 43 Fanzines, 148, 163 Education for Death, 63 Barks Collector, 149, 165, 180 Modern Inventions, 43 Der Donaldist, 157 The New Spirit, 61 Duckburg Times, 157, 158, 180 The Spirit of ‘43, 62 Female characters in Disney comics, 19 Disney Animation, 44, 47, 72 Frontier theory, 85–86, 94 Kimball, Ward, 44 Fuchs, Erika, 6, 15, 16, 105, 152, 201 World War II, 50 early life and career, 125 Disney comics, 177, 180 ”Erikativ,” -

Catalog 2018 General.Pdf

TERRY’S COMICS Welcome to Catalog number twenty-one. Thank you to everyone who ordered from one or more of our previous catalogs and especially Gold and Platinum customers. Please be patient when you call if we are not here, we promise to get back to you as soon as possible. Our normal hours are Monday through Friday 8:00AM-4:00PM Pacific Time. You can always send e-mail requests and we will reply as soon as we are able. This catalog has been expanded to include a large DC selection of comics that were purchased with Jamie Graham of Gram Crackers. All comics that are stickered below $10 have been omitted as well as paperbacks, Digests, Posters and Artwork and many Magazines. I also removed the mid-grade/priced issue if there were more than two copies, if you don't see a middle grade of an issue number, just ask for it. They are available on the regular web-site www.terryscomics.com. If you are looking for non-key comics from the 1980's to present, please send us your want list as we have most every issue from the past 35 years in our warehouse. Over the past two years we have finally been able to process the bulk of the very large DC collection known as the Jerome Wenker Collection. He started collecting comic books in 1983 and has assembled one of the most complete collections of DC comics that were known to exist. He had regular ("newsstand" up until the 1990's) issues, direct afterwards, the collection was only 22 short of being complete (with only 84 incomplete.) This collection is a piece of Comic book history. -

{PDF} Walt Disneys Donald Duck: Lost in the Andes

WALT DISNEYS DONALD DUCK: LOST IN THE ANDES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Carl Barks,Gary Groth | 240 pages | 28 Jun 2012 | Fantagraphics | 9781606994740 | English | Seattle, United States Walt Disneys Donald Duck: Lost in the Andes PDF Book Readers also enjoyed. Read preview. Some of the story notes at the end were interesting while others a bit off-putting, such as "Managing the Ecosystem", some a bit too heavy on the prose for my taste. He packs a lot of expression in the faces and bodies of his characters. Initially, I thought vary little of this, I mean Disney characters were primarily from an animated medium in my mind, and comics based on them weren't anything more than a way to squeeze a few extra merchandizing dollars from your property, right? The line art is crisp and the color is vibrant. Lists with This Book. Related Articles. Our initial volume begins when Barks had reached his peak — Feb 07, Frank rated it it was amazing. Most of the long adventure tales are classics in their own right Discover the genius of Carl Barks! Looking forward to the Uncle Scrooge volume that comes out this summer. As to the content, itself, it's just as remarkable an achievement in comics as I remembered Aug 02, RadioFlash8B rated it liked it. Price Translator. He quickly mastered every aspect of cartooning and over the next nearly 30 years created some of the most memorable comics ever drawn as well as some of the most memorable characters: Barks introduced Uncle Scrooge, the charmed and insufferable Gladstone Gander, the daffy inventor Gyro Gearloose, the bumbling and heedless Beagle Boys, the Junior Woodchucks, and many others. -

Bursting Money Bins the Ice and Water Structure

Bursting Money Bins The ice and water structure Franco Bagnoli, Dept. of Physics and Astronomy and Center for the Study of Complex Dynamics, University of Florence, Italy Via G. Sansone, 1 50019 Sesto Fiorentino (FI) Italy [email protected] In the classic comics by Carl BarKs, “The Big Bin on Killmotor Hill” [1], Uncle Scrooge, trying to defend his money bin from the Beagle Boys, follows a suggestion by Donald DucK, and fills the bin with water. Unfortunately, that night is going be the coldest one in the history of Ducksburg. The water freezes, bursting the ``ten-foot walls'' of the money bin, and finally the gigantic cube of ice and dollars slips down the hill up to the Beagle Boys lot. That water expands when freezing is a well-Known fact, and it is at the basis of an experiment that is often involuntary performed with beer bottles in freezers. But why does the water behave this way? And, more difficult, how can one illustrate this phenomenon in simple terms? First of all, we have to remember that the temperature is related to the Kinetic energy of molecules, which tend to stay in the configuration of minimal energy. In general, if one adopts a simple ball model for atoms, the configuration of minimal energy is more compact than a more energetic (and thus disordered) configuration. But this is not the case for water. FIG. 1: A Schematic representation of the water molecule Indeed, water molecules resemble the head of MicKey Mouse (see Fig. 1), the two hydrogen atoms being the ears. -

General Catalog 2021

TERRY’S COMICS Welcome to Catalog number twenty-four. Thank you to everyone who ordered from one or more of our previous catalogs and especially Gold and Platinum customers. Please be patient when you call if we are not here, we promise to get back to you as soon as possible. Our normal hours are Monday through Friday 9:00AM-5:00PM Pacific Time. You can always send e-mail requests and we will reply as soon as we are able. All comics that are stickered below $10 have been omitted as well as paperbacks, Digests, Posters and Artwork and Magazines. I also removed the mid-grade/priced issue if there were more than two copies, if you do not see a middle grade of an issue number, just ask for it. They are available on the regular website www.terryscomics.com. If you are looking for non-key comics from the 1980's to present, please send us your want list as we have most every issue from the past 35 years in our warehouse. We have been fortunate to still have acquired some amazing comics during this past challenging year. What is left from the British Collection of Pre-code Horror/Sci-Fi selection, has been regraded and repriced according to the current market. 2021 started off great with last year’s catalog and the 1st four Comic book conventions. Unfortunately, after mid- March all the conventions have been cancelled. We still managed to do a couple of mini conventions between lockdowns and did a lot of buying on a trip through several states as far east as Ohio. -

Barks's Personal Reference Library

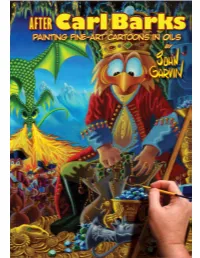

AFTERCarl Barks painting fine-art cartoons in oils by Copyright 2010 by John Garvin www.johngarvin.com Published by Enchanted Images Inc. www.enchantedimages.com All illustrations in this book are copyrighted by their respective copy- right holders (according to the original copyright or publication date as printed in/on the original work) and are reproduced for historical reference and research purposes. Any omission or incorrect informa- tion should be transmitted to the publisher so it can be rectified in future editions of this book. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-9785946-4-0 First “Hunger Print” Edition November 2010 Edition size: 250 Printed in the United States of America about the “hunger” print “Hunger” (01-2010), 16” x 20” oil on masonite. “Hunger” was painted in early 2010 as a tribute to the painting genre pioneered by Carl Barks and to his techniques and craft. Throughout this book, I attempt to show how creative decisions – like those Barks himself might have made – helped shape and evolve the painting as I transformed a blank sheet of masonite into a fine-art cartoon painting. Each copy of After Carl Barks: Painting Fine-Art Cartoons in Oils includes a signed print of the final painting. 5 acknowledgements I am indebted to the following, in paintings and for being an important husband’s work. As the owner of alphabetical order: part of my life. -

Carl Barks' Donald Duck & Co Om Kvalitetene, Leserappellen Og

Carl Barks’ Donald Duck & Co Om kvalitetene, leserappellen og mangelen på anerkjennelse i norske litteraturhistorier Steinar Timenes Masteroppgave i Nordisk språk og litteratur Institutt for lingvistiske, litterære og estetiske studium UNIVERSITETET I BERGEN Først og fremst rettes den største takken til min familie som ga meg det første Donald-bladet fra barnsben av – for det har resultert i denne masteroppgaven. Takk til Arild Midthun og Egmont for bidragene deres! Takk til min veileder Erik Bjerck Hagen for å ha hatt troen på at prosjektet er gjennomførbart! Videre vil jeg takke alle de andre professorene i øverste etasje i HF-bygget for tysk irettesettelse og bergensk sjarm som har gjort studietiden til et akademisk Mekka! Takk for korrekturlesningen, Joakim Tjøstheim! Takk for alle de fuktige kveldene, Vingrisen! Til slutt vil jeg takke alle de flotte menneskene jeg har møtt og vennene jeg har fått under lektorutdanningen. Det er dere som gjør det verdt å komme ut i verdens beste yrke! 2 What is the future of comic books in the modern era? I’m very much scared that comics don’t have a very good future. There will have to be a cycle which reader interest goes back to reading again. Right now, it seems as everybody’s mind is caught up on these new games that come on television and things you can get by touching a button and watching a monitor. Pretty soon the mind will tire of those things and perhaps go back to reading. The wonderful thought of being alone with your thoughts and having something in your hand that you can just read and enjoy rather than having to sit in front of a television monitor looking at somebody else’s stuff moving around on the screen; You’re just a spectator you’re not doing anything to help yourself understand what’s going on.