Contextualizing Disney Comics Within the Arab Culture Jehan Zitawi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disney Comics from Italy♦ © Francesco Stajano 1997-1999

Disney comics from Italy♦ © Francesco Stajano 1997-1999 http://i.am/filologo.disneyano/ A Roberto, amico e cugino So what exactly shall we look at? First of all, the Introduction fascinating “prehistory” (early Thirties) where a few pioneering publishers and creators established a Disney Most of us die-hard Disney fans are in love with those presence in Italy. Then a look at some of the authors, seen comics since our earliest childhood; indeed, many of us through their creations. Because comics are such an learnt to read from the words in Donald’s and Mickey’s obviously visual medium, the graphical artists tend to get balloons. Few of us, though, knew anything about the the lion’s share of the critics’ attention; to compensate for creators of these wonderful comics: they were all this, I have decided to concentrate on the people who calligraphically signed by that “Walt Disney” guy in the actually invent the stories, the script writers (though even first page so we confidently believed that, somewhere in thus I’ve had to miss out many good ones). This seems to America, a man by that name invented and drew each and be a more significant contribution to Disney comics every one of those different stories every week. As we studies since, after all, it will be much easier for you to grew up, the quantity (too many) and quality (too read a lot about the graphical artists somewhere else. And different) of the stories made us realise that this man of course, by discussing stories I will also necessarily could not be doing all this by himself; but still, we touch on the work of the artists anyway. -

Under Exclusive License to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021 PC

INDEX1 A C Adaptation studies, 130, 190 Canon, 94, 146, 187, 188, 193, Adenauer, Konrad, 111, 123 194, 214 Adenauer Era, 105 Cochran, Russ, 164 Another Rainbow, 164, 176 Comics Code, 122 Comics collecting, 146, 161 Cultural diplomacy, 51, 55, 59, B 113, 116 Barks, Carl, 3, 43–44, 61, 62, 69, 185 Calgary Eye-Opener, 72, 156 D early life and career, 71 Dell Comics, 3, 5, 15, 30, 98, “The Good Duck Artist,” 67 123, 143 identifcation by fans, 99 De-Nazifcation, 6, 105 oil portraits, 72, 100, 165 Disney, Walt, 2, 38, 49, 53, 57, 59, retirement, 97 66, 69, 80, 143 Beagle Boys, 74, 135 Disney animated shorts Branding, 39, 56, 57, 66 The Band Concert, 40 Europe, 106 Commando Duck, 65, 121 Bray, J.R., 34 Der Fuehrer’s Face, 62 Col. Heeza Liar, 47 Donald and Pluto, 42 1 Note: Page numbers followed by ‘n’ refer to notes. © The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature 219 Switzerland AG 2021 P. C. Bryan, Creation, Translation, and Adaptation in Donald Duck Comics, Palgrave Fan Studies, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73636-1 220 INDEX Disney animated shorts (cont.) F Donald Gets Drafted, 61 Fan studies, 26, 160 Don Donald, 43 Fanzines, 148, 163 Education for Death, 63 Barks Collector, 149, 165, 180 Modern Inventions, 43 Der Donaldist, 157 The New Spirit, 61 Duckburg Times, 157, 158, 180 The Spirit of ‘43, 62 Female characters in Disney comics, 19 Disney Animation, 44, 47, 72 Frontier theory, 85–86, 94 Kimball, Ward, 44 Fuchs, Erika, 6, 15, 16, 105, 152, 201 World War II, 50 early life and career, 125 Disney comics, 177, 180 ”Erikativ,” -

Catalog 2018 General.Pdf

TERRY’S COMICS Welcome to Catalog number twenty-one. Thank you to everyone who ordered from one or more of our previous catalogs and especially Gold and Platinum customers. Please be patient when you call if we are not here, we promise to get back to you as soon as possible. Our normal hours are Monday through Friday 8:00AM-4:00PM Pacific Time. You can always send e-mail requests and we will reply as soon as we are able. This catalog has been expanded to include a large DC selection of comics that were purchased with Jamie Graham of Gram Crackers. All comics that are stickered below $10 have been omitted as well as paperbacks, Digests, Posters and Artwork and many Magazines. I also removed the mid-grade/priced issue if there were more than two copies, if you don't see a middle grade of an issue number, just ask for it. They are available on the regular web-site www.terryscomics.com. If you are looking for non-key comics from the 1980's to present, please send us your want list as we have most every issue from the past 35 years in our warehouse. Over the past two years we have finally been able to process the bulk of the very large DC collection known as the Jerome Wenker Collection. He started collecting comic books in 1983 and has assembled one of the most complete collections of DC comics that were known to exist. He had regular ("newsstand" up until the 1990's) issues, direct afterwards, the collection was only 22 short of being complete (with only 84 incomplete.) This collection is a piece of Comic book history. -

Bursting Money Bins the Ice and Water Structure

Bursting Money Bins The ice and water structure Franco Bagnoli, Dept. of Physics and Astronomy and Center for the Study of Complex Dynamics, University of Florence, Italy Via G. Sansone, 1 50019 Sesto Fiorentino (FI) Italy [email protected] In the classic comics by Carl BarKs, “The Big Bin on Killmotor Hill” [1], Uncle Scrooge, trying to defend his money bin from the Beagle Boys, follows a suggestion by Donald DucK, and fills the bin with water. Unfortunately, that night is going be the coldest one in the history of Ducksburg. The water freezes, bursting the ``ten-foot walls'' of the money bin, and finally the gigantic cube of ice and dollars slips down the hill up to the Beagle Boys lot. That water expands when freezing is a well-Known fact, and it is at the basis of an experiment that is often involuntary performed with beer bottles in freezers. But why does the water behave this way? And, more difficult, how can one illustrate this phenomenon in simple terms? First of all, we have to remember that the temperature is related to the Kinetic energy of molecules, which tend to stay in the configuration of minimal energy. In general, if one adopts a simple ball model for atoms, the configuration of minimal energy is more compact than a more energetic (and thus disordered) configuration. But this is not the case for water. FIG. 1: A Schematic representation of the water molecule Indeed, water molecules resemble the head of MicKey Mouse (see Fig. 1), the two hydrogen atoms being the ears. -

General Catalog 2021

TERRY’S COMICS Welcome to Catalog number twenty-four. Thank you to everyone who ordered from one or more of our previous catalogs and especially Gold and Platinum customers. Please be patient when you call if we are not here, we promise to get back to you as soon as possible. Our normal hours are Monday through Friday 9:00AM-5:00PM Pacific Time. You can always send e-mail requests and we will reply as soon as we are able. All comics that are stickered below $10 have been omitted as well as paperbacks, Digests, Posters and Artwork and Magazines. I also removed the mid-grade/priced issue if there were more than two copies, if you do not see a middle grade of an issue number, just ask for it. They are available on the regular website www.terryscomics.com. If you are looking for non-key comics from the 1980's to present, please send us your want list as we have most every issue from the past 35 years in our warehouse. We have been fortunate to still have acquired some amazing comics during this past challenging year. What is left from the British Collection of Pre-code Horror/Sci-Fi selection, has been regraded and repriced according to the current market. 2021 started off great with last year’s catalog and the 1st four Comic book conventions. Unfortunately, after mid- March all the conventions have been cancelled. We still managed to do a couple of mini conventions between lockdowns and did a lot of buying on a trip through several states as far east as Ohio. -

Barks's Personal Reference Library

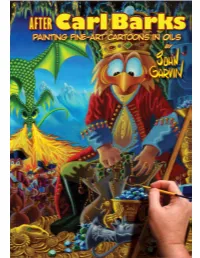

AFTERCarl Barks painting fine-art cartoons in oils by Copyright 2010 by John Garvin www.johngarvin.com Published by Enchanted Images Inc. www.enchantedimages.com All illustrations in this book are copyrighted by their respective copy- right holders (according to the original copyright or publication date as printed in/on the original work) and are reproduced for historical reference and research purposes. Any omission or incorrect informa- tion should be transmitted to the publisher so it can be rectified in future editions of this book. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-9785946-4-0 First “Hunger Print” Edition November 2010 Edition size: 250 Printed in the United States of America about the “hunger” print “Hunger” (01-2010), 16” x 20” oil on masonite. “Hunger” was painted in early 2010 as a tribute to the painting genre pioneered by Carl Barks and to his techniques and craft. Throughout this book, I attempt to show how creative decisions – like those Barks himself might have made – helped shape and evolve the painting as I transformed a blank sheet of masonite into a fine-art cartoon painting. Each copy of After Carl Barks: Painting Fine-Art Cartoons in Oils includes a signed print of the final painting. 5 acknowledgements I am indebted to the following, in paintings and for being an important husband’s work. As the owner of alphabetical order: part of my life. -

Donald Duck from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Donald Duck

Donald Duck From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Donald Duck First appearance The Wise Little Hen (1934) Created by Walt Disney Clarence Nash (1934–1985) Voiced by Tony Anselmo (1985–present) Don Nickname(s) Uncle Donald Duck Avenger (USA) Superduck (UK) Aliases Italian: Paperinik Captain Blue Species Pekin duck Family Duck family Significant other(s) Daisy Duck (girlfriend) Ludwig Von Drake (uncle) Scrooge McDuck (uncle) Relatives Huey, Dewey, and Louie (nephews) Donald Fauntleroy Duck[1] is a cartoon character created in 1934 at Walt Disney Productions and licensed by The Walt Disney Company. Donald is an anthropomorphic white duck with a yellow-orange bill, legs, and feet. He typically wears a sailor suit with a cap and a black or red bow tie. Donald is most famous for his semi-intelligible speech and his explosive temper. Along with his friend Mickey Mouse, Donald is one of the most popular Disney characters and was included in TV Guide's list of the 50 greatest cartoon characters of all time in 2002.[2] He has appeared in more films than any other Disney character[3] and is the fifth most published comic book character in the world after Batman, Superman, Spider-Man, and Wolverine.[4] Donald Duck rose to fame with his comedic roles in animated cartoons. He first appeared in The Wise Little Hen (1934), but it was his second appearance in Orphan's Benefit which introduced him as a temperamental comic foil to Mickey Mouse. Throughout the 1930s, '40s and '50s he appeared in over 150 theatrical films, several of which were recognized at the Academy Awards. -

Donald Duck Comics and U.S. Global Hegemony

Modern American History (2020), 1–26 doi:10.1017/mah.2020.4 ARTICLE Ten-Cent Ideology: Donald Duck Comic Books and the U.S. Challenge to Modernization Daniel Immerwahr The comic-book artist Carl Barks was one of the most-read writers during the years after the Second World War. Millions of children took in his tales of the Disney characters Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge. Often set in the Global South, Barks’s stories offered pointed reflections on foreign relations. Surprisingly, Barks presented a thoroughgoing critique of the main thrust of U.S. foreign policy making: the notion that the United States should intervene to improve “traditional” societies. In Barks’s stories, the best that the inhabitants of rich societies can do is to leave poorer peoples alone. But Barks was not just popular; his work was also influential. High-profile baby boomers such as Steven Spielberg and George Lucas imbibed his comics as children. When they later pro- duced their own creative works in the 1970s and 1980s, they drew from Barks’s language as they too attacked the ideology of modernization. In the 1950s, the U.S. public began to hear a lot about Asia. The continent had “exploded into the center of American life,” wrote novelist James Michener in 1951.1 He was right. The follow- ing years brought popular novels, plays, musicals, and films about the continent. Tom Dooley’s Deliver Us from Evil (1956) and William Lederer and Eugene Burdick’s The Ugly American (1958) shot up the bestsellers’ lists. The novel Teahouse of the August Moon (1951), set in Okinawa, became a Pulitzer- and Tony-winning play (1953) and then a movie starring Marlon Brando (1956). -

Scrooge Mcduck and His Creator by Phillip Salin

Liberty, Art, & Culture Vol. 29, No. 2 Winter 2011 Appreciation: Scrooge McDuck and his Creator By Phillip Salin “Who is Carl Barks?” In the future that question may seem just as the world’s greatest inventor. It was Barks, not Disney, who silly as ‘”Who is Aesop?” invented these and other Duckburg characters and plot devices Phil Salin brings us up to date on the importance of the man who used without attribution by the Disney organization ever since, created Uncle Scrooge... both in print and on the TV screen: Scrooge’s Money Bin, the Junior Woodchucks and their all-encompassing Manual, Once upon a time there was a wonderfully inventive story- Gladstone Gander, Magica DeSpell, Flintheart Glomgold, teller and artist whose works were loved by millions, yet whose and the Beagle Boys. It was Barks, not Disney, who wrote and name was known by no one. Roughly twice a month, for over drew those marvelous, memorable stories, month after month, twenty years, the unknown storyteller wrote and illustrated a year after year, and gave them substance. brand new humorous tale or action adventure for millions of loyal readers, who lived in many countries and spoke many A Taste for Feathers different languages. I started reading Barks’ stories as a kid in the mid-1950s. As The settings of the stories were as wide as the world, indeed I got older, one by one, I gave away or sold most of my other wider: stories were set in mythological and historic places, in comics; but not the Donald Ducks. Somehow they seemed to addition to the most exotic of foreign locales. -

How to Read Donald Duck Was Originally Published in Chile As' Para Leer Al Pato Donald by Ediciones Universitarias De Valparafso, in 1971

MPERIALIST I · . IDEOLOGY . IN THE DISNEY COMIC The Name "Donald Duck" is the Trademark Property and the Cartoon Drawings are the Copyrighted Material Qf Walt Disney Productions. There is no connection between LG. Editions, Inc. and Walt Disney and these materials are used without the authorization or consent of Walt Disney Productions. How to Read Donald Duck was originally published in Chile as' Para Leer al Pato Donald by Ediciones Universitarias de Valparafso, in 1971. Copyright © Ariel Dorfman and I Armand Mattelart 1971 OTHER EDITIONS: Para Leer al Pato Donald, Buenos Aires, 1972 Come Leggere Paperino, Milan, 1972 Para Leer al Pato Donald, Havana, 1974 Para Ler 0 Pato Donald, Lisbon, 1975 Donald I'lmposteur, Paris, 1976 Konsten Att Lasa Kalle Anka, Stockholm, 1977 Walt Disney's "Dritte Welt", Berlin, 1977 Anders And i den Tredje Verden, Copenhagen, 1978 Hoes Lees ik Donald Duck, Nijmegen, 1978 Para LerD Pato Donald, Rio de Janeiro, 1978 with further editions in Greek (1979), Finnish (1980), Japanese (1983), Serbo-Croat, Hungarian and Turkish. How To Read Donald Duck English Translation Copyright@ I.G. Editions, Inc. 1975, 1984, 1991 Preface, lntroduction, Bibliography & Appendix [email protected]. Editions, Inc. 1975,1984,1991 All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher, I.G. Editions, Inc. For information please address I nternational General, Post Office Box 350, New York, N.Y. 10013, USA. ISBN: 0-88477-037-0 Fourth Printing (Corrected & Enlarged Edition) Printed in Hungary 1991 CONTENTS PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION Ariel Dorfman & Armand Mattelart 9 INTRODUCTION TO THE ENGLISH EDITION (1991) David Kunzle 11 APOLOGY FOR DUCKOLOGY 25 INTRODUCTION: INSTRUCTIONS ON HOW TO BECOME A GENERAL IN THE DISNEYLAND CLUB 27 I. -

Ducktales S3 Lead Sheet 2020 Update

"DuckTales" The Emmy® Award-nominated animated comedy-adventure series "DuckTales" chronicles the high-flying adventures of Duckburg's most famous trillionaire Scrooge McDuck; his mischief-making triplet grandnephews, Huey, Dewey and Louie; temperamental nephew, Donald Duck; and the trusted McDuck Manor team: big- hearted, fearless chauffer/pilot Launchpad McQuack, no-nonsense housekeeper Mrs. Beakley and Mrs. Beakley's granddaughter, Webby Vanderquack, resident adventurer and the triplet's fierce friend. After a long overdue family reunion reunites Scrooge with his nephew, grandnephews and epic past, the family of ducks dive into a life more exciting than they could have ever imagined. Featuring a distinct animation style inspired by the classic Carl Barks' comic designs, "DuckTales" celebrates the importance of family and friendship, with comedy, mystery and adventure at every turn. Each 22-minute episode follows the ducks on thrilling explorations as they embrace courage, creativity and the rewards of stepping outside your comfort zone. With relatable and unique personality traits, the next generation of adventurers, Huey, Dewey, Louie and Webby, each embody characteristics of real kids and set examples for young viewers to be confident, curious, independent and innovative. Created for kids, families and kids-at-heart—with several nostalgic nods to the original —the new series tails adventure-obsessed Scrooge McDuck, who has left behind a life of exploration, mystery-solving and globetrotting for a life as a businessman in the city of Duckburg. When Scrooge is unexpectedly reunited with his family, quick-thinking Huey, troublemaking Dewey and fast-talking Louie question everything about their once-legendary great-uncle. Enthralled by Scrooge and the wonder of McDuck Manor, the triplets and Webby learn of long-kept family secrets and unleash totems from his epic past, sending the family—which includes Webby, Mrs. -

Walt Disneys Uncle Scrooge: Only a Poor Old Man PDF Book

WALT DISNEYS UNCLE SCROOGE: ONLY A POOR OLD MAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gary Groth,Carl Barks,George Lucas | 252 pages | 17 Jul 2012 | Fantagraphics | 9781606995358 | English | Seattle, United States Walt Disneys Uncle Scrooge: Only a Poor Old Man PDF Book While many people in my generation may not know about him people they do know Of course, you know it's only a matter of time before teenyboppers start accusing the network of ripping off The Hunger Games , never mind that BR came out years earlier. When Scrooge tries to hide his fortune on a Pacific island, there's of course a fat native who no speak good English, and the natives of Tralla-law are colored yellow and drawn in clothing right out of The Good Earth , suggesting that Barks wasn't fully aware that not all of East Asia is Chinese and that's not even getting into the whole infantilization of the Tralla-laans as people too pure and naive to understand greed. They all explore the philosophy of currency and how a culture gives it its worth, and how human nature drives this. Best Selling in Nonfiction See all. Show More Show Less. Views Total views. First appearance of Scrooge's worry room. I particularly loved the one where Scrooge discovers Donald gave him a n This book collects the first six full comic books from to featuring the classic character Uncle Scrooge. Want to Read saving…. The story begins with Scrooge McDuck swimming in his money bin , speaking his now-famous line, "I love to dive around in it like a porpoise , and burrow through it like a gopher , and toss it up and let it hit me on the head! The writing is stellar -- hilarious, sly, thoughtful, and fun.