The Impact of Standard Italian on a Dialect and a Cultural Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pearl of Lake Como

A B C D E F G H I MAP 1 COMO LOC. RONCHI 1 1 VERGONESE LOC. CRELLA The Pearl of Lake Como LOC. CROTTO VILLA TROTTI S. GIOVANNI 2 P “The most exclusive 2 resort on Lake Como. GUGGIATE So beautiful, so breathtaking, VILLA TRIVULZIO GERLI so comfortable, so unique. MULINI DEL PERLO LOPPIA you’ll feel in heaven. 3 3 VILLA SUIRA MELZI LAGO DI COMO CIVENNA S. PRIMO That’s Bellagio!” MAGREGLIO P ERBA SCEGOLA LIDO TARONICO AUREGGIO CASATE 4 4 P BORGO VISGNOLA P REGATOLA BUS VILLA PARKING P SERBELLONI S. MARTINO VILLA GIULIA PESCALLO PUNTA SPARTIVENTO 5 OLIVERIO 5 S. VITO O ECC LAGO DI LECCO L A B C D E F G H I MAP OF THE CENTRE OF BELLAGIO Boat Terminal Letter Box Imbarcadero Buca delle lettere Car Ferry Terminal Autotraghetto Tourist Office / Ufficio Informazioni Tel. e Fax +39.031.950.204 Bus Terminal Fermata autobus PromoBellagio Office Public toilets Ufficio PromoBellagio Bagni pubblici Tel. e Fax +39.031.951.555 Pharmacy [email protected] Farmacia www.bellagiolakecomo.com T U V W X Y Z GIARDINI DI VILLA MELZI L I D O DI V I A BELLAGIO P . C A R C A N O 1 LAGO 1 LUNGOLA DI COMO R I O EU RO P A P L U N G O L A R IO M A R C O N I CAR FER RY TERMINAL TOURIST OFFICE / UFFICIO INFORMAZIONI BOAT TERMINAL / IMBARCADERO 2 P 2 I MAZZIN PIAZZA A M P O O I O A R I F R E A I F T N D A R A A O I S R N I R U L L V U E NG MANZONI A OLARIO A N A L O C I N R E V M L G O A M P PHARMACY A M C A T PARCO T FARMACIA I I L I C O MUNALE L E I A I A C E N T R A L A V N S N S I O I A A A D A T T T T N ELL A B R BIBLIOTECA ALI ALI ALI ALI G S S S S VIA ER A VIA E. -

Language, Culture, and National Identity

Language, Culture, and National Identity BY ERIC HOBSBAWM LANGUAGE, culture, and national identity is the ·title of my pa per, but its central subject is the situation of languages in cul tures, written or spoken languages still being the main medium of these. More specifically, my subject is "multiculturalism" in sofar as this depends on language. "Nations" come into it, since in the states in which we all live political decisions about how and where languages are used for public purposes (for example, in schools) are crucial. And these states are today commonly iden tified with "nations" as in the term United Nations. This is a dan gerous confusion. So let me begin with a few words about it. Since there are hardly any colonies left, practically all of us today live in independent and sovereign states. With the rarest exceptions, even exiles and refugees live in states, though not their own. It is fairly easy to get agreement about what constitutes such a state, at any rate the modern model of it, which has become the template for all new independent political entities since the late eighteenth century. It is a territory, preferably coherent and demarcated by frontier lines from its neighbors, within which all citizens without exception come under the exclusive rule of the territorial government and the rules under which it operates. Against this there is no appeal, except by authoritarian of that government; for even the superiority of European Community law over national law was established only by the decision of the constituent SOCIAL RESEARCH, Vol. -

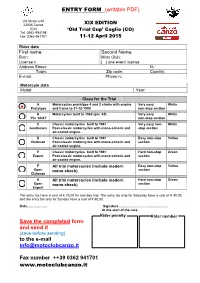

ENTRY FORM (Writable PDF) Save the Completed

ENTRY FORM (writable PDF) Via Meda n.40 22035 Canzo XIX EDITION (Co) ‘Old Trial Cup’ Caglio (CO) Tel. 0362-994198 Fax. 0362-941701 11-12 April 2015 Rider data First name: Second Name: Born: Moto Club: License n. [ ] one event license Address Street: N.: Town: Zip code: Country: E-mail: Phone n.: Motorcyle data Model: Year: Class for the Trial A Motorcycles prototype 4 and 2 stroke with engine Very easy White Prototype and frame to 31-12-1990 non-stop section B Motorcycles built to 1965 (pre ’65) Very easy White Pre ‘65/4T non-stop section C Classic motorcycles built to 1991 Ver y easy non - White Gentlemen Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and stop section air-cooled engine. D Classic motorcycles built to 1991 Easy non -stop Yellow Clubman Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and section air-cooled engine. E Classic motorcycles built to 1991 Hard non -stop Green Expert Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and section air-cooled engine. F All trial motorcycles (include modern Easy non -stop Yellow Open mono shock) section Clubman G All trial motorcycles (include modern Hard non -stop Green Open mono shock) section Expert The entry tax have a cost of € 75,00 for two day trial. The entry tax only for Saturday have a cost of € 40,00 and the entry tax only for Sunday have a cost of € 40,00. Data……………… Signature……………………………………… At the start of the race Rider penalty Rider number Save the completed form and send it (save before sending) to the e-mail [email protected] Fax number ++39 0362 941701 www.motoclubcanzo.it How reach the trial in Caglio (CO) From Turin : Highway Turin-Milan following on the west ring of Milan to direction Venice and exit to Cinisello Balsamo toward the highway Milan-Lecco direction Lecco. -

The Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry in Lombardy

The Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry in Lombardy RICERCA N°07/2016 Edited by Gruppo Chimici and Centro Studi The Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry in Lombardy This Research has been carried out by: Centro Studi and Gruppo Chimici, Assolombarda Confindustria Milano Monza e Brianza Centro Studi, Farmindustria Centro Studi, Federchimica We thank Unioncamere Lombardia for industrial production data Contents 1. FOREWORD 5 2. THE CHEMICAL AND PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY IN LOMBARDY 6 Key figures 6 The size of the industry 9 Industrial production trends between 2007 and the second quarter of 2016 11 The international perspective 12 R&D activities 14 1. Foreword I am very pleased to disclose to you “The Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry in Lombardy”. This research is promoted by Gruppo Chimici Assolombarda, a group of firms associated to Assolombarda Confindustria Milano Monza e Brianza currently including about 680 companies and almost 50,000 employees, which I have the honour to represent. The aim is to provide an all-round analysis and work tool, acting as a basis for an industrial policy proposal that recognises the significance of those sectors, both at local and national level. Lombardy is particularly cut out for the Chemical and Pharmaceutical industry, thanks to an efficient network of companies and industrial clients, universities and research centres, plant design companies and advanced services. The Chemical and Pharmaceutical industry means innovation. It stays ahead of the market and lays the basis for future Italian growth. The crisis has not left us unscathed, but the Chemical and Pharmaceutical industry is recovering from the crisis, with Lombardy giving a head start. -

Elenco Candidati Per Colloqui

SERVIZIO CIVILE NAZIONALE PROGETTI 2012 - BANDO STRAORDINARIO 2014 CALENDARIO COLLOQUI DI SELEZIONE DEI CANDIDATI Progetto CONCILIARE CON CURA SEDE: PROVINCIA DI LECCO SALA RIUNIONI 5° PIANO C.SO COLLOQUIO MERCOLEDI' 10 DICEMBRE ORE 14:00 MATTEOTTI 3 SEDE PROGETTO NOMINATIVO OLIVETO LARIO COLOMBO LAURA OLIVETO LARIO AZZOLINI MARTA OLIVETO LARIO LERDER FEDERICA OLIVETO LARIO ZAINA GIUSEPPE SEDE: PROVINCIA DI LECCO AULA CORSI PIANO TERRA CORSO COLLOQUIO LUNEDI' 15 DICEMBRE ORE 09.00 MATTEOTTI 3 - LECCO SEDE PROGETTO NOMINATIVO GARLATE PANZERI ALESSANDRA GARLATE BORGHETTI SILVIA GARLATE GADDI VALERIA GARLATE MAFFEI MARCO GARLATE INVERNIZZI GIULIA ELENA GARLATE MAGGI VALERIA GARLATE ZAGARELLA GIOVANNA GARLATE ANGHILERI ANDREA GARLATE ABATE FEDERICA GARLATE RIGAMONTI NICOLE GARLATE RUBERTO SIMONA SEDE: PROVINCIA DI LECCO AULA CORSI PIANO TERRA CORSO COLLOQUIO LUNEDI' 15 DICEMBRE ORE 11.00 MATTEOTTI 3 - LECCO SEDE PROGETTO NOMINATIVO BOSISIO PARINI LIGAS GIULIANA BOSISIO PARINI CARRUBBA GIULIA BOSISIO PARINI SCOTTI CHIARA BOSISIO PARINI SISTO SAMANTHA BOSISIO PARINI NEMBRINI STEFANO BOSISIO PARINI CAIETTI DEBORAH SERVIZIO CIVILE NAZIONALE PROGETTI 2012 - BANDO STRAORDINARIO 2014 CALENDARIO COLLOQUI DI SELEZIONE DEI CANDIDATI Progetto PROMUOVERE PER SOSTENERE: ANZIANI AL CENTRO SEDE: PROVINCIA DI LECCO SALA RIUNIONI 5° PIANO C.SO COLLOQUIO MERCOLEDI' 10 DICEMBRE ORE 9:00 MATTEOTTI 3 SEDE PROGETTO NOMINATIVO MONTEVECCHIA VIGANO' ALESSIA SEDE: PROVINCIA DI LECCO SALA RIUNIONI 5° PIANO C.SO COLLOQUIO MERCOLEDI' 10 DICEMBRE ORE 14:30 MATTEOTTI 3 SEDE PROGETTO NOMINATIVO CALOLZIOCORTE CORNO MARTA CALOLZIOCORTE VALSECCHI BEATRICE CALOLZIOCORTE EL MAMARI MARCELLO CALOLZIOCORTE PEZZANO ALICE CALOLZIOCORTE SCORDAMAGLIA SIMONA CALOLZIOCORTE SALA GIULIA CALOLZIOCORTE BIELLA LUCA CALOLZIOCORTE BAIO SIMONE CALOLZIOCORTE MILESI ELISA SERVIZIO CIVILE NAZIONALE PROGETTI 2012 - BANDO STRAORDINARIO 2014 CALENDARIO COLLOQUI DI SELEZIONE DEI CANDIDATI Progetto TESTIMONI DEL PASSATO. -

Linea D60 LECCO

IN VIGORE DAL 13 SETTEMBRE 2021 LECCO SEREGNO D60 Fer6 Sco6 Sco5 Sco6 Sco6 Sco6 Sco6 Sco6 Fer6 Sco5 Sco5 Sco6 Sco6 Sco6 Sco6 Fer6 Sco6 Fer6 Sco6 Sco6 Sco6 Fer6 Sco6 Fer6 Fer6 Sco6 Sab Sab Sco6 Fer6 Sco6 Sab Sco5 ANDATA 2 40 40 6464 1 64 LECCO F.S. 6:35 8:20 9:25 9:45 11:58 VALMADRERA F.S. 6:42 8:27 9:32 9:52 12:05 VALMADRERA (Via Roma) 7:34 8:29 CIVATE LA SANTA 7:38 8:33 SUELLO 7:43 8:38 ANNONE (Palestra) SALA AL BARRO 6:46 9:36 9:56 12:09 OGGIONO (Casa di Riposo) 6:52 10:02 12:15 OGGIONO FS 6:35 6:55 7:07 7:30 7:35 7:50 7:52 7:52 7:55 8:00 8:05 8:10 8:40 8:37 8:42 8:47 9:00 10:35 10:35 11:30 11:37 12:20 DOLZAGO (POSTA) 6:40 7:12 7:35 7:40 7:55 7:57 7:57 8:05 8:15 8:45 8:42 8:52 9:05 9:47 10:07 10:40 10:40 11:35 11:42 CASTELLO ( BRIANZ.) 8:02 10:45 11:40 CASTELLO COMUNE 8:05 10:48 11:43 CASTELLO PREST. 8:10 10:53 11:48 ROVAGNATE SIRONE 6:44 7:17 7:39 7:44 8:00 8:05 8:19 8:46 8:52 9:09 9:5110:1110:44 11:46 BRONGIO (VIA PROV.) 6:46 7:41 7:46 8:21 8:48 9:11 9:5310:1310:46 11:48 GARBAGNATE 7:21 8:04 8:09 8:56 BRONGIO (VIA MILANO) 7:24 8:07 8:12 8:59 BARZAGO 7:28 8:11 8:16 9:03 BEVERA VIA LECCO 6:50 7:45 7:50 8:01 8:10 8:25 8:50 8:52 8:57 9:15 9:5710:1710:50 11:52 BEVERA (VIA PROV.) 7:31 8:14 8:19 9:06 BARZANO' 6:35 6:49 6:55 7:05 7:34 7:50 7:55 8:17 8:04 8:22 8:15 8:15 8:30 8:55 8:40 8:57 9:09 9:01 9:20 10:02 10:22 10:55 11:20 11:50 11:58 11:57 12:00 SIRTORI 6:53 VIGANO' 6:57 7:10 TORREVILLA 6:39 6:59 7:38 7:59 8:21 8:44 11:24 11:54 MISSAGLIA Molinata 7:00 7:01 8:01 MISSAGLIA V. -

Scuole Infanzia Paritarie

SCUOLE INFANZIA PARITARIE Via/ Codice Telefono Indirizzo posta elettronica N. Denominazione Scuola Comune Piaz Indirizzo scuola CAP E-mail scuola Sito internet meccanografico scuola certificata . CASA DEL BAMBINO ABBADIA asilo.casadelbambino@virgili si.casadelbambino.abbad www.scuolainfanziaabbad 1 LC1A03600E LARIANA Via ALL'ASILO 18 23821 0341 730201 o.it [email protected] ialariana.it PARROCCHIA S. ANTONIO GESTIONE ABBADIA MAGGIANA - FRAZ. si.santonio.crebbio@pec 2 LC1A074009 SCUOLA MATERNA LARIANA Via CREBBIO 23821 0341 730278 [email protected] 2.fismlecco.it S. GIOACHINO AL CASTELLO 3 LC1A102008 BALLABIO Via ALDO MORO 13 23811 0341 530169 [email protected] [email protected] SCUOLA DELL'INFANZIA S. GIUSEPPE 4 LC1A020001 BARZAGO Via ROMA 4 23890 031 860327 [email protected] [email protected] SCUOLA PRIMAVERA LEONARDO DA 5 LC1A08700B BARZANO' Via VINCI 18 23891 039 956297 [email protected] ecco.it www.scuolaprimavera.it SCUOLA DELL'INFANZIA S. www.mariareginadeimont 6 LC1A04400D ALESSANDRO BARZIO Via MILANO 19 23816 0341 917006 [email protected] [email protected] i.it SCUOLA DELL'INFANZIA TOMMASO MARTIRI DELLA amministrazione@maternabe si.tommasogrossi@pec2. 7 LC1A09200V GROSSI BELLANO Via LIBERTA' 18 23822 0341 821214 llano.it fismlecco.it www.maternabellano.it SCUOLA DELL'INFANZIA CESARE scuolainfanziabrivio@pe 8 LC1A03400V CANTU' BRIVIO Via COMO 2 23883 039 5320136 [email protected] c.it SCUOLA DELL'INFANZIA GIULIO GIULIO PRINETTI [email protected] 9 -

Dialects, Standards, and Vernaculars

1 Dialects, Standards, and Vernaculars Most of us have had the experience of sitting in a public place and eavesdropping on conversations taking place around the United States. We pretend to be preoccupied, but we can’t seem to help listening. And we form impressions of speakers based not only on the topic of conversation, but on how people are discussing it. In fact, there’s a good chance that the most critical part of our impression comes from how people talk rather than what they are talking about. We judge people’s regional background, social stat us, ethnicity, and a host of other social and personal traits based simply on the kind of language they are using. We may have similar kinds of reactions in telephone conversations, as we try to associate a set of characteristics with an unidentified speaker in order to make claims such as, “It sounds like a salesperson of some type” or “It sounds like the auto mechanic.” In fact, it is surprising how little conversation it takes to draw conclusions about a speaker’s background – a sentence, a phrase, or even a word is often enough to trigger a regional, social, or ethnic classification. Video: What an accent does Assessments of a complex set of social characteristics and personality traits based on language differences are as inevitable as the kinds of judgments we make when we find out where people live, what their occupations are, where they went to school, and who their friends are. Language differences, in fact, may serve as the single most reliable indicator of social position in our society. -

Antiche Civiltà Turistiche Lecco Milano - Lecco (Via Molteno) Palazzo Delle Paure Dalla Stazione Di Milano Porta Garibaldi Piazza XX Settembre, 23 Tel

informazioni ® www.ecomuseomontilaghibriantei.it Civico Museo di Erba Lavatoio UFFICIO INFORMAZIONI COME ARRIVARE IN TRENO antiche civiltà TURISTICHE LECCO Milano - Lecco (via Molteno) Palazzo delle Paure dalla stazione di Milano Porta Garibaldi Piazza XX Settembre, 23 Tel. 0341.295.720 Como San Giovanni -Lecco dalla stazione Como San Giovanni UFFICIO INFORMAZIONI TURISTICHE CANZO Milano Nord - Erba- Canzo/Asso Piazza della Chiesa 4 dalla stazione di Milano Cadorna Tel. 031.682.457 (Aperto solo nei mesi estivi) COME ARRIVARE IN AUTO UFFICIO INFORMAZIONI TURISTICHE COMO Milano - Lecco Piazza Cavour 17 Prendere la SS Nuova Valassina (Viale Tel. 031.269.712 Zara-Fulvio Testi) e proseguire per 50 km ecomuseo del distretto dei monti e laghi briantei www.lakecomo.it Como - Lecco Prendere la SS342, poi la SS 36 in direzione Lecco EDIZIONE MARZO 2014 L’ITINERARIO MASSI ERRATICI, In epoche più o meno INFO MASSI DELLE COPPELLE, recenti furono integrati L’ itinerario sulle tracce MASSO AVELLO Comune di Erba al paesaggio e utilizzati www.comune.erba.co.it di antiche civiltà che nei MONTE BARRO come fontanili o lavatoi. GALBIATE (LC) [email protected] secoli hanno colonizzato Una delle testimonianze ed abitato l’area brian- più significative è il tea. Un viaggio tra reper- lavatoio di Suello, le cui LAGO DI PUSIANO ti archeologici risalenti al vasche derivano dalla In Italia, ai piedi delle Alpi Neolitico, conservati nel riutilizzazione e parziale e nella bassa Lombardia, Civico Museo di Erba e rilavorazione di coperchi numerose erano le di sarcofagi tardo-antichi nel Museo Archeologico stazioni preistoriche sui in serizzo. del Barro (MAB). -

Archivio Storico Del Comune Di Galbiate Parte Ii Inventario Degli Archivi Dei

ARCHIVIO STORICO DEL COMUNE DI GALBIATE PARTE II INVENTARIO DEGLI ARCHIVI DEI COMUNI AGGREGATI AL COMUNE DI GALBIATE a cura della dott.ssa Lucia Ronchetti e della dott.ssa Marina Bonifazio marzo 1996 INDICE DEL VOLUME - Note introduttive p. 1 - Tavola delle abbreviazioni p. 3 I. ARCHIVIO DEL COMUNE DI BARTESATE (INVENTARIO A CURA DELLA DOTT.SSA MARINA BONIFAZIO) - Notizie storico-giuridiche p. 5 - Cenni storici sull’archivio p. 7 - Carteggio ordinato in base alle XV categorie ministeriali p. 14 - Serie particolari: Conti Consuntivi p. 32 Liste di leva p. 34 Ruoli matricolari p. 35 Fogli di famiglia – Registri di popolazione p. 36 Registri di Stato Civile (registri degli atti di nascita, morte, matrimonio e cittadinanza) p. 37 Registri (registri delle deliberazioni del Consiglio Comunale, registri delle pratiche cimiteriali, repertori degli atti soggetti a tassa) p. 39 - ARCHIVIO DELLA CONGREGAZIONE DI CARITÀ DEL COMUNE DI BARTESATE Notizie storico-giuridiche p. 41 Cenni storici sull’archivio p. 41 Carteggio p. 42 Conti consuntivi p. 43 Registri p. 43 - Indici (indice delle persone, dei toponimi, delle istituzioni) p. 44 II. ARCHIVIO DEL COMUNE DI SALA AL BARRO (INVENTARIO A CURA DELLA DOTT.SSA LUCIA RONCHETTI) - Notizie storico-giuridiche p. 50 - Cenni storici sull’archivio p. 52 - Carteggio ordinato in base alle XV categorie ministeriali p. 54 - Serie particolari: Conti Consuntivi p. 85 Liste di leva p. 87 Ruoli matricolari p. 88 Fogli di famiglia – Registri di popolazione p. 89 Anagrafe napoleonica (registri degli atti di nascita, morte e matrimonio) p. 92 Registri di Stato Civile (registri degli atti di nascita, morte, matrimonio e cittadinanza) p. -

Intonation of Sicilian Among Southern Italo-Romance Dialects Valentina De Iacovo, Antonio Romano

Intonation of Sicilian among Southern Italo-romance dialects Valentina De Iacovo, Antonio Romano Laboratorio di Fonetica Sperimentale “A. Genre”, Univ. degli Studi di Torino, Italy [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT At a second stage, we select the most frequent pattern found in the data for each modality (also closest to the Dialects of Italy are a good reference to show how description provided by [10]) and compare it with prosody plays a specific role in terms of diatopic other Southern Italo-romance varieties with the aim variation. Although previous experimental studies of verifying a potential similarity with other Southern have contributed to classify a selection of some and Upper Southern varieties. profiles on the basis of some Italian samples from this region and a detailed description is available for some 2. METHODOLOGY dialects, a reference framework is still missing. In this paper a collection of Southern Italo-romance varieties 2.1. Materials and speakers is presented: based on a dialectometrical approach, For the first experiment, data was part of a more we attempt to illustrate a more detailed classification extensive corpus available online which considers the prosodic proximity between (http://www.lfsag.unito.it/ark/trm_index.html, see Sicilian samples and other dialects belonging to the also [4]). We select 31 out of 40 recordings Upper Southern and Southern dialectal areas. The representing 21 Sicilian dialects (9 of them were results, based on the analysis of various corpora, discarded because their intonation was considered show the presence of different prosodic profiles either too close to Standard Italian or underspecified regarding the Sicilian area and a distinction among in terms of prosodic strength). -

Comune Di Osnago Verbale Di Deliberazione Della Giunta Comunale

COMUNE DI OSNAGO PROVINCIA DI LECCO Viale Rimembranze, 3 - Tel. 039952991 - Fax 0399529926 Codice Fiscale 00556800134 DELIBERAZIONE N° 121 DEL 11/07/2008 Trasmessa in elenco ai Capigruppo con nota Prot. n. ORIGINALE VERBALE DI DELIBERAZIONE DELLA GIUNTA COMUNALE OGGETTO: APPROVAZIONE PROTOCOLLO D'INTESA TRA LA PROVINCIA DI LECCO ED I COMUNI DI SIRTORI, CERNUSCO LOMBARDONE, LOMAGNA, MERATE, MISSAGLIA, MONTEVECCHIA, OLGIATE MOLGORA, OSNAGO, PEREGO, ROVAGNATE, VIGANÒ, IL PARCO DI MONTEVECCHIA E VALLE DEL CURONE, IL CONSORZIO BRIANTEO VILLA GREPPI PER L'ORGANIZZAZIONE DEL FESTIVAL "ULTIMA LUNA D'ESTATE" ANNO 2008 L'anno duemilaotto, addì undici del mese di luglio alle ore 18.30, nella Sala delle Adunanze. Previa l’osservanza di tutte le formalità prescritte dalla vigente Legge, vennero oggi convocati a seduta i componenti la Giunta Comunale. All’appello risultano: Firma Presenze STRINA DOTT. PAOLO Sindaco NO TIENGO ANGELO Assessore SI BELLANO PIERALDO Assessore SI LORENZET DANIELE Assessore NO POZZI ALESSANDRO Assessore SI CAGLIO GABRIELE Assessore SI PRESENTI: 4 ASSENTI: 2 Assiste all’adunanza IL SEGRETARIO GENERALE RENDA DOTT.SSA ROSA la quale provvede alla redazione del presente verbale. Essendo legale il numero degli intervenuti il Vice Sindaco, Sig. ANGELO TIENGO, assume la presidenza e dichiara aperta la seduta per la trattazione dell’oggetto sopra indicato. COMUNE DI OSNAGO PROVINCIA DI LECCO Viale Rimembranze, 3 - Tel. 039952991 - Fax 0399529926 Codice Fiscale 00556800134 OGGETTO: APPROVAZIONE PROTOCOLLO D’INTESA TRA LA PROVINCIA