The Buildings of the Visigothic Elite: Function and Material Culture in Spaces of Power1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Questions for Art of Medieval Spain

www.YoYoBrain.com - Accelerators for Memory and Learning Questions for Art of Medieval Spain Category: Default - (74 questions) Alabaster sculpture of Tanit/Astarte, nicknamed "Dama de Galera," Madrid, Museo Arqueológico, 7th c BCE -Phinecean object that found home in Iberian religious practices -Phineceans: eastern culture; experts in maritime travel; traded with Iberian locals; began settling in coastal cities around mouth of the mediterranean around 8th cen. BCE Sculpture of Askepios, from Empùries, 2 c BCE -Greek Empuries -from Sanctuary of Askepios (God of Medicine) Dama de Baza, 4th c. CE -reminiscent of ancient Greek Chios Kore -from native culture of Iberia: culturally receptive but politically resistant to invading groups; independent tribes) -rise of votive figure echo to the Phineceans Head of Augustus, early 1st c. CE -sculpture from Merida (sculptures from this area were among the finest on the peninsula) -Merida (aka Augusta Emerita) was a military settlement; founded by Augustus for retired soldiers; not founded on a pre-existing site which is different from ordinary Roman towns in Spain; became a politically important city Mérida, theater, inscr. 15-16 BC -attached to amphitheater; deliberate connection -attributed to Augustus -well preserved -partly reconstructed (scenae frons- elaborate, built later during Hadrian period) Tarragona (Tarraco), Arch of Bará, 2nd c CE -Tarragona was capital of Eastern Roman Spain (being on top of a hill, it was hard to attack and therefore a good place for a capital) -The arch is just outside -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

THE MAN AND THE MYTH: HERACLIUS AND THE LEGEND OF THE LAST ROMAN EMPEROR By CHRISTOPHER BONURA A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Christopher Bonura 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my adviser, Dr. Andrea Sterk, for all the help and support she has given me, not just for this thesis, but for her patience and guidance throughout my time as her student. I would never have made it to this point without her help. I would like to thank Dr. Florin Curta for introducing me to the study of medieval history, for being there for me with advice and encouragement. I would like to thank Dr. Bonnie Effros for all her help and support, and for letting me clutter the Center for the Humanities office with all my books. And I would like to thank Dr. Nina Caputo, who has always been generous with suggestions and useful input, and who has helped guide my research. My parents and brother also deserve thanks. In addition, I feel it is necessary to thank the Interlibrary loan office, for all I put them through in getting books for me. Finally, I would like to thank all my friends and colleagues in the history department, whose support and friendship made my time studying at the University of Florida bearable, and often even fun, especially Anna Lankina-Webb, Rebecca Devlin, Ralph Patrello, Alana Lord, Eleanor Deumens, Robert McEachnie, Sean Hill, Sean Platzer, Bryan Behl, Andrew Welton, and Miller Krause. -

Framing Power in Visigothic Society

LATE ANTIQUE AND EARLY MEDIEVAL IBERIA Dell’ Elicine & Martin (eds.) Framing Power in Visigothic Power SocietyFraming Edited by Eleonora Dell’ Elicine and Céline Martin Framing Power in Visigothic Society Discourses, Devices, and Artifacts FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Framing Power in Visigothic Society FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Late Antique and Early Medieval Iberia Scholarship on the Iberian Peninsula in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages is burgeoning across a variety of disciplines and time periods, yet the publication profile of the field remains disjointed. ‘Late Antique and Early Medieval Iberia’ (LAEMI) provides a publication hub for high-quality research on Iberian Studies from the fijields of history, archaeology, theology and religious studies, numismatics, palaeography, music, and cognate disciplines. Another key aim of the series is to break down barriers between the excellent scholarship that takes place in Iberia and Latin America and the Anglophone world. Series Editor Jamie Wood, University of Lincoln, UK Editorial Board Andrew Fear, University of Manchester, UK Nicola Clarke, Newcastle University, UK Inaki Martín Viso, University of Salamanca, Spain Glaire Anderson, University of North Carolina, USA Eleonora Dell’Elicine, University of Buenos Aires, Argentina FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Framing Power in Visigothic Society Discourses, Devices, and Artefacts Edited by Eleonora Dell’ Elicine and Céline Martin Amsterdam University Press FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Cover illustration: Golden ring of Teudericus, found at Romelle (Samos, Lugo). End of 6th to 7th century. Madrid, M.A.N, Inventory Number 62193 Cover design: Coördeisgn, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 590 3 e-isbn 978 90 4854 359 5 doi 10.5117/9789463725903 nur 684 © E. -

Medieval Mediterranean Influence in the Treasury of San Marco Claire

Circular Inspirations: Medieval Mediterranean Influence in the Treasury of San Marco Claire Rasmussen Thesis Submitted to the Department of Art For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts 2019 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. Introduction………………………...………………………………………….3 II. Myths……………………………………………………………………….....9 a. Historical Myths…………………………………………………………...9 b. Treasury Myths…………………………………………………………..28 III. Mediums and Materials………………………………………………………34 IV. Mergings……………………………………………………………………..38 a. Shared Taste……………………………………………………………...40 i. Global Networks…………………………………………………40 ii. Byzantine Influence……………………………………………...55 b. Unique Taste……………………………………………………………..60 V. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………...68 VI. Appendix………………………………………………………………….….73 VII. List of Figures………………………………………………………………..93 VIII. Works Cited…………………………………………………...……………104 3 I. Introduction In the Treasury of San Marco, there is an object of three parts (Figure 1). Its largest section piece of transparent crystal, carved into the shape of a grotto. Inside this temple is a metal figurine of Mary, her hands outstretched. At the bottom, the crystal grotto is fixed to a Byzantine crown decorated with enamels. Each part originated from a dramatically different time and place. The crystal was either carved in Imperial Rome prior to the fourth century or in 9th or 10th century Cairo at the time of the Fatimid dynasty. The figure of Mary is from thirteenth century Venice, and the votive crown is Byzantine, made by craftsmen in the 8th or 9th century. The object resembles a Frankenstein’s monster of a sculpture, an amalgamation of pieces fused together that were meant to used apart. But to call it a Frankenstein would be to suggest that the object’s parts are wildly mismatched and clumsily sewn together, and is to dismiss the beauty of the crystal grotto, for each of its individual components is finely made: the crystal is intricately carved, the figure of Mary elegant, and the crown vivid and colorful. -

Diocesis Hispaniarum (3Rd-5Th Century)

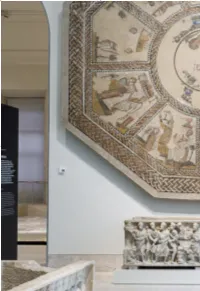

003 ROMA_english_Maquetación 1 21/02/14 11:33 Página 64 003 ROMA_english_Maquetación 1 21/02/14 11:33 Página 65 From Late Antiquity to Middle Age 004 MEDIEVAL_english_Maquetación 1 21/02/14 11:42 Página 66 Diocesis Hispaniarum (3rd-5th Century) The third century was a period of political and economic instability for the Roman Empire, which culminated with the reign of Diocletian. Under his rule, Hispania was divided into five provinces which together formed the Diocesis Hispaniarum. The fourth century brought a revival of economic prosperity, especially during the reign of the Hispano-Roman emperor Theo- dosius. The growing importance of the rural villas, the new residences of the Hispano-Roman aristocracy, would mark the course of the fourth and fifth centuries. In 380 Theodosius declared Christianity the empire’s official religion, crea- 66 ting a new ideological instrument of power with far-reaching political, ad- ministrative and social consequences. The origins of Christianity in Hispania are heterogeneous, with influences pouring in from North Africa, Rome and other places where important communities had existed since the third cen- tury. Everyday objects like the ones in the display case incorporated Christian symbols such as the Chi-Rho. The exhibition also features sarcophagi with relief decoration, a mosaic memorial plaque and gravestone inscriptions in memory of the dead. Reccesvinth’s crown (The Guarrazar Hoard) > 004 MEDIEVAL_english_Maquetación 1 21/02/14 11:42 Página 67 004 MEDIEVAL_english_Maquetación 1 21/02/14 11:42 Página 68 The Visigothic Kingdom of Toledo (6th-8th Century) After being defeated by the Franks at the Battle of Vouillé (507), the Visi- goths consolidated their power on the Iberian Peninsula and established To- ledo as their capital. -

Byzantine” Crowns: Between East, West and the Ritual

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Seminář dějin umění Bc. Teodora Georgievová “Byzantine” Crowns: between East, West and the Ritual Diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Doc. Ivan Foletti, M.A. 2019 Prehlasujem, že som diplomovú prácu vypracovala samostatne s využitím uvedených prameňov a literatúry. Podpis autora práce First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor doc. Ivan Foletti for the time he spent proofreading this thesis, for his valuable advice and comments. Without his help, I would not be able to spend a semester at the University of Padova and use its libraries, which played a key role in my research. I also thank Valentina Cantone, who kindly took me in during my stay and allowed me to consult with her. I’m grateful to the head of the Department of Art History Radka Nokkala Miltová for the opportunity to extend the deadline and finish the thesis with less stress. My gratitude also goes to friends and colleagues for inspiring discussions, encouragement and unavailable study materials. Last but not least, I must thank my parents, sister and Jakub for their patience and psychological support. Without them it would not be possible to complete this work. Table of Contents: Introduction 6 What are Byzantium and Byzantine art 7 Status quaestionis 9 Coronation ritual 9 The votive crown of Leo VI 11 The Holy Crown of Hungary 13 The crown of Constantine IX Monomachos 15 The crown of Constance of Aragon 17 1. Byzantine crowns as objects 19 1.1 The votive crown of Leo VI 19 1.1.1 Crown of Leo VI: a votive offering? 19 1.1.2 Iconography and composition of the crown 20 1.1.3 Contacts between Venice and Constantinople, and the history of Leo VI’s crown 21 1.1.4 Role of the votive crowns in sacral space 23 . -

What the World Would Be Without Inventions?

What the world would be without inventions? GREEK INVENTORS THROUGH TIME “The introduction of noble inventions seems to hold by far the most excellent place among human actions” ~ Francis Bacon 7 Greek inventors through time • Archimides • Euclid • Pythagoras • Thucydides • Ctesibius of Alexandria • Constantin Carathéodory • George Papanikolaou Archimides, the great mathematician and inventor of the “Archimides principle” GREEK INVENTORS I Archimedes of Syracuse (Ancient Greek: Ἀρχιμήδης [ar.kʰi.mɛː.dɛ̂ːs]; c . 287 – c. 212 BC) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, en gineer, inventor, and astronomer. He is regarded as one of the leading scientists in classical antiquity. Considered to be the greatest mathematician of ancient history, and one of the greatest of all time, Archimedes anticipated modern calculus and analysis by applying concepts of infinitesimals and the method of exhaustion to derive and rigorously prove a range of geometrical theorems, including: the area of a circle; the surface area and volume of a sphere; area of an ellipse; the area under a parabola; the volume of a segment of a paraboloid of revolution; the volume of a segment of a hyperboloid of revolution; and the area of a spiral. His other mathematical achievements include deriving an accurate approximation of pi; defining and investigating the spiral that now bears his name; and creating a system using exponentiation for expressing very large numbers. He was also one of the first to apply mathematics to physical phenomena, founding hydrostatics and statics, including an explanation of the principle of the lever. He is credited with designing innovative machines, such as his screw pump, compound pulleys, and defensive war machines to protect his native Syracuse from invasion. -

Cambridge Histories Online

Cambridge Histories Online http://universitypublishingonline.org/cambridge/histories/ The New Cambridge Medieval History Edited by Paul Fouracre Book DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521362917 Online ISBN: 9781139053938 Hardback ISBN: 9780521362917 Paperback ISBN: 9781107449060 Chapter 13 - The Catholic Visigothic kingdom pp. 346-370 Chapter DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521362917.015 Cambridge University Press chapter 13 THE CATHOLIC VISIGOTHIC KINGDOM A. Barbero and M. I. Loring With the abandonment of Arianism at the Third Council of Toledo in 589, there began a new phase in the evolution of the Visigothic kingdom. Religious unification facilitated the definitive rapprochement of the Gothic nobility and upper classes of Roman origin, and allowed the Catholic church, the principal repository of the old Roman culture, to acquire a growing prominence in the political life of the kingdom.1 This active political role was expressed principally through the series of national church councils in Toledo, the regal metropolis, initiated by that of 589.Inthese the church seemed to play the role of arbiter between the royal power and the high nobility, although a close reading of the conciliar acts reveals its tendency to act in solidarity with the secular nobility. Kings, on the other hand, only exceptionally made use of the councils in order to assert their authority and were generally obliged to negotiate in the face of the powerful secular nobility and church, this being one of the main causes of the weakness of centralised authority. Religious unification also made way for a progressive interpenetration of the spiritual and temporal spheres at every level of Visigothic life and society, in which the former shaped the whole dominant ideological structure. -

Santiago Castellanos, Iñaki Martín Viso the Local Articulation of Central Power in the North of the Iberian Peninsula, 500-1000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Reti Medievali Open Archive Santiago Castellanos, Iñaki Martín Viso The local articulation of central power in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, 500-1000 [A stampa in “Early Medieval Europe”, 13 (2005), 1, pp. 1-42 © degli autori – Distribuito in formato digitale da “Reti Medievali”, www.biblioteca.retimedievali.it]. The local articulation of central power in the north of the Iberian Peninsula (500–1000) S C I M V Envisaging political power as dynamic allows the historian to deal with its structures with some sophistication. This paper approaches political power, not as a circumscribed block of bureaucratic elements, but as a complex phenomenon rooted in social reality. The authors explore the dialogue between local and central power, understanding ‘dialogue’ in its widest sense. Thus the relationships (both amicable and hostile) between local and central spheres of influence are studied. The authors propose a new analytical framework for the study of the configuration of political power in the northern zone of the Iberian peninsula, over a long period of time, which takes in both the post-Roman world and the political structures of the early Middle Ages. The organization of political power in the post-Roman west has been the focus of much scholarly reappraisal in the last few years. One might have thought, however, that, thanks to the study of institutions, we have been aware for some time of the realities of power which lay behind the political structures emerging in the west from the fifth century onwards. -

Outline —Discussion Class 2

OUTLINE — DISCUSSION CLASS 2 The Germanic Peoples and Their ‘Codes’ The Germanic Invasions The map might be entitled all-hell-breaks-loose, and there are even more inelegant ways to describe it. As we will see, the map probably exaggerates the amount of disruption, but it does show that between the years 150 and 1000, a great many tribes, mostly but not exclusively Germanic, made their way into what was or had formerly been the Roman empire in the West, and this development had far-reaching consequences for Western European history and particularly for its law. http://www.law.harvard.edu/faculty/cdonahue/courses/CLH/Slides/01_Shep045_11_01_24.jpg Germanic Language Groups: West North East OHG ONorse Gothic OSax ONeth OFris OEng Germanic Kingdoms in 486: http://www.law.harvard.edu/faculty/cdonahue/courses/CLH/Slides/03_Shep050_11_01_24(486).jpg West Center East Anglo-Saxon Saxons Saxons Franks Franks Thuringians Visigoths Alemanni ? ? ? Burgundians Ostrogoths Odoacer Germanic Kingdoms in 600: http://www.law.harvard.edu/faculty/cdonahue/courses/CLH/Slides/02_Shep052b_11_01_24_ERomanEmp_600.jpg West Center East Anglo-Saxon Saxons Saxons Franks Franks Thuringians Visigoths Lombards Bavarians The Chief Monuments of Roman Law in the Period of the ‘Germanic Kingdoms’: a. The lex romana visigothorum (breviarium Alarici) (Alaric II, 506) Bibliog: Lex romana visigothorum, G. Haenel ed. (1845); Breviarium Alarici, M. Conrat (Cohn) ed. & trans. (1890) b. The lex romana burgundionum (Gundobad 506) Bibliog: Leges Burgundionum, ed. F. Bluhme (MGH Leges 3, 1863, repr. 1925); Leges Burgundionum, ed. L.R. von Salis (MGH Legum sec. 1, Leges nationum Germanicarum 2.1, 1892); Gesetze der Burgunden, F. -

Visigothic Spain

THE ENGLISH HISTORICAL REVIEW Downloaded from NO. VL—APRIL 1887 Visigothic Spain http://ehr.oxfordjournals.org/ E foundation of the Visigothic state in Spain and southern rGaul is one of the most interesting and remarkable chapters in the history of the barbarian migrations; and it illustrates, in some ways with exceptional clearness, the Anglo-Saxon period of our own history. For the Visigoths, like our forefathers, were a people who, having at first raged exceedingly against the faith held throughout at Georgetown University on July 19, 2015 the Boman empire, were afterwards themselves won over to profess it, though the Visigoth's rancour was that of the Arian Christian, while the Saxon's was that of the unreclaimed heathen. Being thus brought into obedience to the law of the catholic church, Visigoth as well as Saxon distinguished him naif "by the abjectnesa of bin submission to his spiritual rulers. And perhaps partly in conse- quence of the prominent place thenceforward taken by ecclesiastics in the administration of the state, both Visigoth and Saxon were found wanting in virility and vigour when the day came for defend- ing their country against the heathen or the ^fnaHniman invader. In the following paper I propose to indicate some of the most important phases in the development of the Visigothic state, follow- ing chiefly the guidance of Professor Dahn, who in the sixth volume of bis ' Konige der Germanen' (lately republished in a second edition) has treated with thoroughness and patience all the more important questions connected with the constitutional history of the Visigoths. -

Spain's Early History the People of the Iberian Peninsula Joined European History As the Rival

“A Country of Immigrants”: Spain’s Early History The people of the Iberian Peninsula joined European history as the rivalry between the Greeks and the Phoenicians, two nations blessed with a high degree of cultural development, played itself out on Spanish soil. This rivalry was eventually brought to an end when Rome es- tablished superior forms of urban living and civilization in Hispania - the Latin name of the peninsula - and tied it forevermore to the known western world. The Most Ancient Peoples: Assuming the authenticity and dating of the human fossil discovered in Orce in the province of Granada is correct, the most ancient human in Europe walked this land around one and a half million years ago. Other proof of human habitation exists all over Spain, such as the marvellous caverns of Altamira in Cantabria, which were only discovered in 1879, and are of- ten compared to the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican in Rome. The paintings in these deep caves are naturalistic and polychrome and depict many of the animals found in this northern part of Spain at this time. The function of the paintings, beyond their aesthetic value, may have been religious or served some other symbolic purpose. Other sites of prehistoric art also exist in Spain such as the black and ochre stick figure drawings found at the mouth of other caves in south-eastern Spain. Unlike the Altamira paint- ings, these drawings include human figures and are narrative in nature. Again, their function is unknown. The Catalan drawings, such as these from the cave of Cogull, belong to the Palaeolithic era.