Dual Kingship in the Kofun Period As Seen from the Keyhole Tombs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei By ©2016 Alison Miller Submitted to the graduate degree program in the History of Art and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko ________________________________ Dr. Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Dr. David Cateforis ________________________________ Dr. John Pultz ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama Date Defended: April 15, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Alison Miller certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko Date approved: April 15, 2016 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the political significance of the image of the Japanese Empress Teimei (1884-1951) with a focus on issues of gender and class. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Japanese society underwent significant changes in a short amount of time. After the intense modernizations of the late nineteenth century, the start of the twentieth century witnessed an increase in overseas militarism, turbulent domestic politics, an evolving middle class, and the expansion of roles for women to play outside the home. As such, the early decades of the twentieth century in Japan were a crucial period for the formation of modern ideas about femininity and womanhood. Before, during, and after the rule of her husband Emperor Taishō (1879-1926; r. 1912-1926), Empress Teimei held a highly public role, and was frequently seen in a variety of visual media. -

Muko City, Kyoto

Muko city, Kyoto 1 Section 1 Nature and(Geographical Environment and Weather) 1. Geographical Environment Muko city is located at the southwest part of the Kyoto Basin. Traveling the Yodo River upward from the Osaka Bay through the narrow area between Mt. Tenno, the famous warfield of Battle of Yamazaki that determined the future of this country, and Mt. Otoko, the home of Iwashimizu Hachimangu Shrine, one of the three major hachimangu shrines in Japan, the city sits where three rivers of the Katsura, the Uji and the Kizu merge and form the Yodo River. On west, Kyoto Nishiyama Mountain Range including Mt. Oshio lays and the Katsura River runs on our east. We share three boundaries with Kyoto city - the northern and western boundaries with Nishikyo-ku, and the eastern boundary with Minami-ku and Fushimi-ku. Across the southern boundary is Nagaokakyo city abutting Oyamazaki-cho which is the neighbor of Osaka Prefecture. The city is approximiately 2km from east to west and approximiately 4km from south to north covering the 7.72km2 area. This makes us the third smallest city in Japan after Warabi city and Komae city. Figure 1-1-1 Location of Muko city (Right figure (Kyoto map) : The place of red is Muko city) (Lower figure (Japan map) : The place of red is Kyoto) N W E S 1 Geographically, it is a flatland with the northwestern part higher and the southwestern part lower. This divides the city coverage into three distinctive parts of the hilly area in the west formed by the Osaka Geo Group which is believed to be cumulated several tens of thousands to several million years ago, the terrace in the center, and the alluvial plain in the east formed by the Katsura River and the Obata River. -

Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group: Mounded Tombs of Ancient Japan

Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group: Mounded Tombs of Ancient Japan [ Main Document ] 2018 JAPAN Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group Mounded Tombs of Ancient Japan Executive Summary Executive Summary Executive Summary 1. State Party Japan 2. State, Province or Region Osaka Prefecture 3. Name of the Property Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group: Mounded Tombs of Ancient Japan 4. Geographical coordinates to the nearest second Table e-1 Component parts of the nominated property and their locations Coordinate of the central point ID Name of the No. component part Region / District Latitude Longitude 1 Hanzei-tenno-ryo Kofun Sakai City N 34° 34’ 34” E 135° 29’ 18” Nintoku-tenno-ryo Kofun, Chayama Kofun and Daianjiyama Kofun 2-1 Nintoku-tenno-ryo Kofun 2 Sakai City N 34° 33’ 53” E 135° 29’ 16” 2-2 Chayama Kofun 2-3 Daianjiyama Kofun 3 Nagayama Kofun Sakai City N 34° 34’ 05” E 135° 29’ 12” 4 Genemonyama Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 54” E 135° 29’ 28” 5 Tsukamawari Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 46” E 135° 29’ 26” 6 Osamezuka Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 31” E 135° 29’ 16” 7 Magodayuyama Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 36” E 135° 29’ 06” 8 Tatsusayama Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 40” E 135° 29’ 00” 9 Dogameyama Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 46” E 135° 28’ 56” 10 Komoyamazuka Kofun Sakai City N 34° 34’ 01” E 135° 29’ 03” 11 Maruhoyama Kofun Sakai City N 34° 34’ 01” E 135° 29’ 07” 12 Nagatsuka Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 29” E 135° 29’ 16” 13 Hatazuka Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 24” E 135° 28’ 58” Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group e 001 Executive Summary Coordinate of the central point ID Name of the No. -

Jomon: 11Th to 3Rd Century BCE Yayoi

Outline Lecture Sixteen—Early Japanese Mythology and Shinto Ethics General Chronology: Jomon: 11th to 3rd century B.C.E. Yayoi: 3rd B.C.E. to 3rd C.E. Tomb: 3rd to 6th C.E. Yamato: 6th to 7th C.E. I) Prehistoric Origins a) Early Japanese history shrouded in obscurity i) Writing did not develop in Japan until 6th century C.E. ii) No remains of cities or other large scale settlements iii) Theories of origins of earliest settlers b) Jomon (Roughly 11th to 3rd century B.C.E.) i) “Rope-pattern” pottery ii) Hunter-gathering settlements iii) Lack of social stratification? c) Yayoi (3rd B.C.E. to 3rd C.E.) i) Simultaneous introduction of irrigation, bronze, and iron contributing to revolutionary changes (1) Impact of change in continental civilizations tend to be more gradual (2) In Japan, effect of changes are more dramatic due to its isolation (a) Foreign elements trickle in, then blend with indigenous elements (b) Creating a distinctive synthesis in “petri-dish” (pea-tree) environment ii) Increasing signs of specialization and social stratification (1) Objects of art—less primitive, more self-conscious (2) Late Yayoi burial practices d) Tomb or Kofun Period (3rd to 7th) i) Large and extravagant tombs in modern day Osaka ii) What beliefs about the afterlife do they reflect? (1) Two strains in Japanese religious cosmology iii) Emergence of a powerful mounted warrior class iv) Regional aristocracies each with its clan name (1) Uji vs. Be (2) Dramatic increase in social stratification e) Yamato State (6th to 8th C.E.) II) Yamato’s Constructions -

The Creation of National Treasures and Monuments: the 1916 Japanese Laws on the Preservation of Korean Remains and Relics and Their Colonial Legacies Hyung Il Pai

The Creation of National Treasures and Monuments: The 1916 Japanese Laws on the Preservation of Korean Remains and Relics and Their Colonial Legacies Hyung Il Pai This article surveys the history of Korea’s heritage management laws and administration beginning with the current divisions of the Office of Cultural Properties and tracing its structure back to the 1916 Japanese Preservations Laws governing Korean remains and relics. It focuses on the eighty-year-old bureaucratic process that has led to the creation of a distinct Korean patrimony, now codified and ranked in the nationally designated registry of cultural properties (Chijông munhwajae). Due to the long-standing perceived “authentic” status of this sanctified list of widely recognized “Korean” national treasures, they have been preserved, reconstructed, and exhibited as tangible symbols of Korean identity and antiquity since the early colonial era. The Office of Cultural Properties and the Creation of Korean Civilization The Office of Cultural Properties (Munhwajae Kwalliguk, hereafter re- ferred to as the OCP) since its foundation in 1961 has been the main institution responsible for the legislation, identification, registration, collection, preserva- tion, excavations, reconstruction and exhibitions of national treasures, archi- tectural monuments, and folk resources in the Republic of Korea.1 This office used to operate under the Ministry of Culture and Sports, but, due to its ever- expanding role, it was awarded independent ministry (ch’ông) status in 1998. With a working staff of more than five hundred employees, it also oversees a vast administrative structure including the following prominent cultural insti- tutions: the Research Institute of Cultural Properties (Munhwajae Yôn’guso) founded in 1975; the two central museums, the National and Folk Museum, which are in charge of an extended network of nine national museums (located in Kyôngju, Kwangju, Chônju, Ch’ôngju, Puyô, Kongju, Taegu, Kimhae, and Korean Studies, Volume 25, No. -

Artful Adventures JAPAN an Interactive Guide for Families 56

Artful Adventures JAPAN An interactive guide for families 56 Your Japanese Adventure Awaits You! f See inside for details JAPAN Japan is a country located on the other side of the world from the United States. It is a group of islands, called an archipelago. Japan is a very old country and the Japanese people have been making beautiful artwork for thousands of years. Today we are going to look at ancient objects from Japan as well as more recent works of Japanese art. Go down the stairs to the lower level of the Museum. At the bottom of the steps, turn left and walk through the Chinese gallery to the Japanese gallery. Find a clay pot with swirling patterns on it (see picture to the left). This pot was made between 2,500 and 1,000 b.c., during the Late Jōmon period—it is between 3,000 and 4,500 years old! The people who lived in Japan at this time were hunter-gatherers, which means that they hunted wild animals and gathered roots and plants for food. The Jomon people started forming small communities, and began to make objects that were both beautiful and useful— like this pot which is decorated with an interesting pattern and was used for storage. Take a close look at the designs on this pot. Can you think of some words to describe these designs? Japanese, Middle to Late Jōmon period, ca. 3500–ca. 1000 B.C.: jar. Earthenware, h. 26.0 cm. 1. ............................................................................................................. Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund (2002-297). -

Matrix: a Journal for Matricultural Studies “In the Beginning, Woman

Volume 02, Issue 1 March 2021 Pg. 13-33 Matrix: A Journal for Matricultural Studies M https://www.networkonculture.ca/activities/matrix “In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun”: Takamure Itsue’s Historical Reconstructions as Matricultural Explorations YASUKO SATO, PhD Abstract Takamure Itsue (1894-1964), the most distinguished pioneer of feminist historiography in Japan, identified Japan’s antiquity as a matricultural society with the use of the phrase ‘women-centered culture’ (josei chūshin no bunka). The ancient classics of Japan informed her about the maternalistic values embodied in matrilocal residence patterns, and in women’s beauty, intelligence, and radiance. Her scholarship provided the first strictly empirical verification of the famous line from Hiratsuka Raichō (1886-1971), “In the beginning, woman was the sun.” Takamure recognized matricentric structures as the socioeconomic conditions necessary for women to express their inner genius, participate fully in public life, and live like goddesses. This paper explores Takamure’s reconstruction of the marriage rules of ancient Japanese society and her pursuit of the underlying principles of matriculture. Like Hiratsuka, Takamure was a maternalist feminist who advocated the centrality of women’s identity as mothers in feminist struggles and upheld maternal empowerment as the ultimate basis of women’s empowerment. This epochal insight into the ‘woman question’ merits serious analytic attention because the principle of formal equality still visibly disadvantages women with children. Keywords Japanese women, Ancient Japan, matriculture, Takamure Itsue, Hiratsuka Raicho ***** Takamure Itsue (1894-1964), pionière éminente de l'historiographie feministe au Japon, a découvert dans l'antiquité japonaise une société matricuturelle qu'elle a identifiée comme: une 'société centrée sur les femmes' (josei chūshin no bunka) ou société gynocentrique. -

The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’S Subjugation of Silla

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1993 20/2-3 The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’s Subjugation of Silla Akima Toshio In prewar Japan, the mythical tale of Empress Jingii’s 神功皇后 conquest of the Korean kingdoms comprised an important part of elementary school history education, and was utilized to justify Japan5s coloniza tion of Korea. After the war the same story came to be interpreted by some Japanese historians—most prominently Egami Namio— as proof or the exact opposite, namely, as evidence of a conquest of Japan by a people of nomadic origin who came from Korea. This theory, known as the horse-rider theory, has found more than a few enthusiastic sup porters amone Korean historians and the Japanese reading public, as well as some Western scholars. There are also several Japanese spe cialists in Japanese history and Japan-Korea relations who have been influenced by the theory, although most have not accepted the idea (Egami himself started as a specialist in the history of northeast Asia).1 * The first draft of this essay was written during my fellowship with the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, and was read in a seminar organized by the institu tion on 31 January 199丄. 1 am indebted to all researchers at the center who participated in the seminar for their many valuable suggestions. I would also like to express my gratitude to Umehara Takeshi, the director general of the center, and Nakanism Susumu, also of the center, who made my research there possible. -

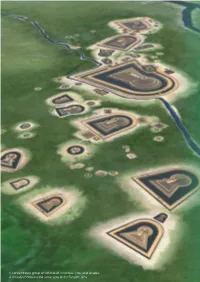

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group

Mahorashiroyama Yamatogawa River Sakai-Higashi Sakaishi Sakai Exit [Exhibition facility] 南海本線 Shukuin 170 WORLD HERITAGE SITE What is kofun? Terajicho Sakai City Hall What is the Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group? Observatory Lobby Osaka Chuo Loop Line 170 Nintoku-tenno-ryo Kofun Sakai-Yamatotakada Line Fujiidera Public Library Kofun is a collective term for the ancient tombs with earthen mounds that 湊 御陵前 [Exhibition facility] The World Heritage property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb Ryonannomori Synthesis Pyramid of Cheops Fujiidera Center 12 Fujiidera City Hall were actively constructed in the Japanese archipelago from the middle of 26 I.C. Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group group of the king’s clan that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago. Mausoleum of [Exhibition facility] the 3rd century to the late 6th century CE. In those days, members of the Hajinosato The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late the First Qin Emperor 30 Takawashi Fujiidera high-ranking elite were buried in kofun. Kintetsu Minami-Osaka Line Mounded Tombs of Ancient Japan 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period. They are located Mikunigaoka in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important Domyoji A burial mound was constructed by heaping up the soil that was dug 197 AICEL Shura Hall political cultural centers and a maritime gateway to the Asian continent. from the ground around the mound site. The sloping sides of the mound [Exhibition facility] were covered with stones, and the excavated area formed a moat, Mozuhachiman The kofun group includes many tombs in the shape of a keyhole, descending to a level lower than any other part of the tomb. -

Rites and Rituals of the Kofun Period

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1992 19/2-3 Rites and Rituals of the Kofun Period I s h in o H ironobu 石野博信 The rituals of the Kofun period were closely connected with both daily life and political affairs. The chieftain presided over the principal rites, whether in the mountains, on the rivers, or along the roadsides. The chieftain’s funeral was the preeminent rite, with a tomb mound, or kofun, constructed as its finale. The many and varied kofun rituals have been discussed elsewhere;1 here I shall concentrate on other kami rites and their departure from Yayoi practices. A Ritual Revolution Around AD 190, following a period of warfare called the “Wa Unrest,” the overall leadership of Wa was assumed by Himiko [Pimiko], female ruler of the petty kingdom of Yamatai. Beginning in 239 she opened diplomatic relations with the Wei court in China as the monarch of Wa, and she died around 248. Makimuku 1 type pottery appeared around 190; in 220 or so it was followed by Makimuku 2,and then by Makimuku 3, in about 250. The 92-meter-long keyhole-shaped Makimuku Ishizuka tomb in Sakurai City, Nara, was constructed in the first half of the third century; in the latter half of the same century the Hashihaka tomb was built. Hence the reign of Himiko, circa 190 to 248,corresponds to the appearance of key hole-shaped tombs. It was the dawn of the Kofun period and a formative time in Kofun-period ritual. In the Initial Kofun, by which I mean the period traditionally assigned to the very end of the Yayoi, bronze ritual objects were smashed, dis * This article is a partial translation of the introductory essay to volume 3 of Ish in o et al. -

Origin of Shinto : Ancient Japanese Rituals

Kokugakuin Univercity Museum Origin of Shinto : Ancient Japanese Rituals 14 September (Sat.) - 10 December (Sun.) , 2017 № Title Provenance Date Collection ■ Introduction 1 Mirror with Design of Seven arcs Okinoshima site, Munakata city, Fukuoka pref. Kofun period, 4th century Owned by Kokugakuin University Museum ■ ChapterⅠ: What is "Sinto " ? 1:Views of "Shinto " in the "Nihon Shyoki " : "Shinto " as the state religion Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan) vol.21 Edited in 720, Nara period 2 Edited by Prince Toneri and others Owned by Kokugakuin University Library "The record before the enthronement of Emperor Yomei " Published in Edo period Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan) vol.25 Edited in 720, Nara period 3 Edited by Prince Toneri and others Owned by Kokugakuin University Library "The record before the enthronement of Emperor Kotoku " Published in Edo period Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan) vol.20 Edited in 720, Nara period 4 Edited by Prince Toneri and others Owned by Kokugakuin University Library "The record before the enthronement of Emperor Bidatsu" Published in Edo period Edited in 779, Nara period 5 To Daiwajo Toseiden (Eastern Expedition of the Great Tang Monk) Edited by Omi Mifune Owned by Kokugakuin University Library Published in Edo period Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan), vol.25 Edited in 720, Nara period 6 Edited by Prince Toneri Owned by Kokugakuin University Library "October, the 3rd year of Taika (647)" Published in Edo period 2:The word of "Shinto " : The Shinto view of the spirit Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan) vol.19