STORIES of STARS and ACROBATS Forms of Theatre Between Turkey and Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste Représentative Du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel De L'humanité

Liste représentative du patrimoine culturel immatériel de l’humanité Date de Date récente proclamation Intitulé officiel Pays d’inscriptio Référence ou première n inscription Al-Ayyala, un art traditionnel du Oman - Émirats spectacle dans le Sultanat d’Oman et 2014 2014 01012 arabes unis aux Émirats arabes unis Al-Zajal, poésie déclamée ou chantée Liban 2014 2014 01000 L’art et le symbolisme traditionnels du kelaghayi, fabrication et port de foulards Azerbaïdjan 2014 2014 00669 en soie pour les femmes L’art traditionnel kazakh du dombra kuï Kazakhstan 2014 2014 00011 L’askiya, l’art de la plaisanterie Ouzbékistan 2014 2014 00011 Le baile chino Chili 2014 2014 00988 Bosnie- La broderie de Zmijanje 2014 2014 00990 Herzégovine Le cante alentejano, chant polyphonique Portugal 2014 2014 01007 de l’Alentejo (sud du Portugal) Le cercle de capoeira Brésil 2014 2014 00892 Le chant traditionnel Arirang dans la République 2014 2014 00914 République populaire démocratique de populaire Date de Date récente proclamation Intitulé officiel Pays d’inscriptio Référence ou première n inscription Corée démocratique de Corée Les chants populaires ví et giặm de Viet Nam 2014 2014 01008 Nghệ Tĩnh Connaissances et savoir-faire traditionnels liés à la fabrication des Kazakhstan - 2014 2014 00998 yourtes kirghizes et kazakhes (habitat Kirghizistan nomade des peuples turciques) La danse rituelle au tambour royal Burundi 2014 2014 00989 Ebru, l’art turc du papier marbré Turquie 2014 2014 00644 La fabrication artisanale traditionnelle d’ustensiles en laiton et en -

Türk Dünyası Öğrencilerinin Unesco Somut Olmayan Kültür Mirası

TÜRK DÜNYASI ÖĞRENCİLERİNİN UNESCO SOMUT OLMAYAN KÜLTÜR MİRASI DEĞERLERİNE İLİŞKİN BİLGİ VE DENEYİM DÜZEYLERİNİN KARŞILAŞTIRILMASI Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article Akkuş, Ç. (2020). Türk Dünyası Öğrencilerinin Geliş Tarihi: 21.07.2020 Unesco Somut Olmayan Kültür Mirası Değerlerine Kabul Tarihi: 20.12.2020 İlişkin Bilgi ve Deneyim Düzeylerinin E-ISSN: 2149-3871 Karşılaştırılması. Nevşehir Hacı Bektaş Veli Üniversitesi SBE Dergisi, 10(2), 608-624. DOI: 10.30783/nevsosbilen.772492 Çetin AKKUŞ Kastamonu Üniversitesi, Turizm Fakültesi, Turizm İşletmeciliği Bölümü [email protected] ORCID No: 0000-0002-6539-726X ÖZ Bu araştırmada Türk Cumhuriyetlerinden Türkiye’ye lisans öğrenimi amacıyla gelmiş üniversite öğrencilerinin kendi ülkelerinin UNESCO Somut Olmayan Kültürel Miras Listesi’nde yer alan kaynaklarına ilişkin bilgi ve deneyim düzeylerini tespit etmek amaçlanmıştır. Ayrıca listede bazı ortak değerleri tescillenen Türk Dünyası ülkeleri öğrencilerinin bu değerlere ilişkin bilgi ve deneyim düzeylerinin farklılığını saptamak hedeflenmiştir. Bu amaçla Kastamonu Üniversitesi’nde öğrenim gören Türkiye vatandaşı öğrenciler ile Azerbaycan, Kazakistan, Kırgızistan, Özbekistan ve Türkmenistan’dan gelen toplam 399 öğrenciye ulaşılmıştır. Ulaşılan verilere tanımlayıcı istatistikler ve farklılık analizleri yapılmıştır. Araştırma sonucunda en yüksek bilgi ve deneyim ortalamasına sahip ülke Kırgızistan olurken bunu sırasıyla Azerbaycan, Kazakistan, Türkmenistan, Türkiye, Özbekistan takip etmiştir. Kültürel miras değerleri içerisinde en bilinen unsurlar; Azerbaycan, Kazakistan ve Türkmenistan için Nevruz, Kırgızistan için Kırgız Destan Üçlemesi, Özbekistan için Özbek pilavı ve Türkiye için Karagöz olmuştur. Vatandaşları tarafından en az bilinen unsurlar ise; Azerbaycan için Çevgen oyunu, Kırgızistan için ekmek (lavaş, yufka) yapma kültürü, Kazakistan için Doğan- Şahinle avlanma, Özbekistan için Katta Ashula ve Boysun ilçesi kültürel alanı, Türkmenistan için Geleneksel Türk halı yapım sanatı ve son olarak Türkiye için Islık Dili ve Semah olmuştur. -

Hansel and Gretel” to America: a Study and Translation of a Puppet Show

BRINGING POCCI'S “HANSEL AND GRETEL” TO AMERICA: A STUDY AND TRANSLATION OF A PUPPET SHOW Daniel Kline A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2008 Committee: Dr. Christina Guenther, Advisor Bradford Clark, Advisor Dr. Kristie Foell Margaret McCubbin ii ABSTRACT Dr. Christina Guenther, Co-Advisor; Bradford Clark, Co-Advisor My thesis introduces the German-puppet character Kasperl to English-language scholars. I provide historical background on the evolution of the Kasperl figure and explore its political uses, its role in children’s theatre, and the use of puppet theatre as an alternative means of performance. The section on the political uses of the figure focuses mainly on propaganda during the First and Second World Wars, but also touches on other developments during the Weimar Republic and in the post-war era. The television program Kasperl and the use of Kasperl for education and indoctrination are two major features in the section concerning children’s theatre. In the second section of the thesis, my study focuses on the German puppet theatre dramatist Franz von Pocci (1807-1876) and his works. I examine Pocci’s theatrical texts, positing him as an author who wrote not only for children’s theatre. Within this section, I interpret several of his texts and highlight the way in which he challenges the artistic and scientific communities of his time. Finally, I analyze and translate his puppet play Hänsel und Gretel: Oder der Menschenfresser. In the analysis I explore issues concerning science, family, government agencies, and morality. -

The Concept of Self and the Other

Tel Aviv University The Yolanda and David Katz Faculty of the Arts Department of Theatre Studies The Realm of the Other: Jesters, Gods, and Aliens in Shadowplay Thesis Submitted for the Degree of “Doctor of Philosophy” by Chu Fa Ching Ebert Submitted to the Senate of Tel Aviv University April 2004 This thesis was supervised by Prof. Jacob Raz TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF ILLUSTRATIONS................................................................................................vi INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................... 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... 7 I. THE CONCEPT OF SELF AND THE OTHER.................................................................... 10 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 11 The Multiple Self .................................................................................................................... 12 Reversal Theory...................................................................................................................... 13 Contextual Theory ................................................................................................................. 14 Self in Cross‐Cultural Perspective ‐ The Concept of Jen................................................... 17 Self .......................................................................................................................................... -

Puppetry Beyond Entertainment, How Puppets Are Used Politically to Aid Society

PUPPETRY BEYOND ENTERTAINMENT, HOW PUPPETS ARE USED POLITICALLY TO AID SOCIETY By Emily Soord This research project is submitted to the Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama, Cardiff, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Theatre Design April 2008 i Declaration I declare that this Research Project is the result of my own efforts. The various sources to which I am indebted are clearly indicated in the references in the text or in the bibliography. I further declare that this work has never been accepted in the substance of any degree, and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any other degree. Name: (Candidate) Name: (Supervisor) ii Acknowledgements Many people have helped and inspired me in writing this dissertation and I would like to acknowledge them. My thanks‟ to Tina Reeves, who suggested „puppetry‟ as a subject to research. Writing this dissertation has opened my eyes to an extraordinary medium and through researching the subject I have met some extraordinary people. I am grateful to everyone who has taken the time to fill out a survey or questionnaire, your feedback has been invaluable. My thanks‟ to Jill Salen, for her continual support, inspiration, reassurance and words of advice. My gratitude to friends and family for reading and re-reading my work, for keeping me company seeing numerous shows, for sharing their experiences of puppetry and for such interesting discussions on the subject. Also a big thank you to my dad and my brother, they are both technological experts! iii Abstract Puppets are extraordinary. -

List of the 90 Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage

Albania • Albanian Folk Iso-Polyphony (2005) Algeria • The Ahellil of Gourara (2005) Armenia • The Duduk and its Music (2005) Azerbaijan • Azerbaijani Mugham (2003) List of the 90 Masterpieces Bangladesh • Baul Songs (2005) of the Oral and Belgium • The Carnival of Binche (2003) Intangible Belgium, France Heritage of • Processional Giants and Dragons in Belgium and Humanity France (2005) proclaimed Belize, Guatemala, by UNESCO Honduras, Nicaragua • Language, Dance and Music of the Garifuna (2001) Benin, Nigeria and Tog o • The Oral Heritage of Gelede (2001) Bhutan • The Mask Dance of the Drums from Drametse (2005) Bolivia • The Carnival Oruro (2001) • The Andean Cosmovision of the Kallawaya (2003) Brazil • Oral and Graphic Expressions of the Wajapi (2003) • The Samba de Roda of Recôncavo of Bahia (2005) Bulgaria • The Bistritsa Babi – Archaic Polyphony, Dances and Rituals from the Shoplouk Region (2003) Cambodia • The Royal Ballet of Cambodia (2003) • Sbek Thom, Khmer Shadow Theatre (2005) Central African Republic • The Polyphonic Singing of the Aka Pygmies of Central Africa (2003) China • Kun Qu Opera (2001) • The Guqin and its Music (2003) • The Uyghur Muqam of Xinjiang (2005) Colombia • The Carnival of Barranquilla (2003) • The Cultural Space of Palenque de San Basilio (2005) Costa Rica • Oxherding and Oxcart Traditions in Costa Rica (2005) Côte d’Ivoire • The Gbofe of Afounkaha - the Music of the Transverse Trumps of the Tagbana Community (2001) Cuba • La Tumba Francesa (2003) Czech Republic • Slovácko Verbunk, Recruit Dances (2005) -

A Book of Operas

A Book of Operas Henry Edward Krehbiel A Book of Operas Table of Contents A Book of Operas................................................................................................................................................1 Henry Edward Krehbiel...........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. "IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA"........................................................................................1 CHAPTER II. "LE NOZZE DI FIGARO"..............................................................................................7 CHAPTER III. "DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE"...............................................................................................14 CHAPTER IV. "DON GIOVANNI".....................................................................................................20 CHAPTER V. "FIDELIO".....................................................................................................................27 CHAPTER VI. "FAUST"......................................................................................................................34 CHAPTER VII. "MEFISTOFELE".......................................................................................................39 CHAPTER VIII. "LA DAMNATION DE FAUST".............................................................................47 CHAPTER IX. "LA TRAVIATA"........................................................................................................50 CHAPTER -

PERFORMING the LABORING CLASS: the EVOLUTION of PUNCH and JUDY PERFORMANCE by Kathryn Meehan, BA a Thesis Submitted to The

PERFORMING THE LABORING CLASS: THE EVOLUTION OF PUNCH AND JUDY PERFORMANCE by Kathryn Meehan, BA A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in Theatre August 2014 Committee Members: John Fleming Sandra Mayo Margaret Eleanor Menninger 1 COPYRIGHT by Kate Meehan 2014 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgment. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Kate Meehan, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank Dr. Margaret Eleanor Menninger, whose support for my work in theatre as an historical tool has been unwavering, and Dr. John Fleming and Dr. Sandra Mayo, who also served as readers for this thesis. I would be remiss if I didn’t thank Adam Rodriguez, La Fenice’s most popular Pulcinella, for providing invaluable insight into the character’s modern interpretation and serving as a sounding board for much of this thesis. Also due recognition is Olly Crick, whose decade-long support of my work as both a performer and academic is much appreciated. Special thanks also to my husband, Stephen Brent Jenkins, and our children, who were both encouraging and understanding throughout the writing of this document. -

Livree 1.Pdf

p i L BRAR ES PUBLIC LIBRARY THE BRANCH 3 3333 02373 0530 --&~f- JL b y SB>^^ "- * A BOOK OF MARIONETTES c o -o o ^ I a _= z ~ c/i 4-1 (LI O. o. 3 a. A BOOK ofj MARIONETTES by HELEN HAIMAN JOSEPH SX I -'* **'} v >. ...... York B. W. HUEBSCH COPYRIGHT, 1920, BY B. W. HUEBSCH To my Father ELIAS HAIMAN With pride and love for the brave simplicity and gentle nobility of his life '* . i . i > - > * -, .* .*- ',. r?rs; : V .*' , ", -;-- Note THE story of the marionette is endless, in fact it has neither beginning nor end. The marionette has been everywhere and is everywhere. One cannot write of the puppets without saying more than one had in- tended and less than one desired: there is such a piquant insistency in them. The purpose of this book is altogether modest, but the length of it has grown to be presumptuous. As to its merit, that must be found in the subject matter and in the sources from which the material was gathered. If this volume is but a sign-post pointing the way to better historians and friends of the puppets and through them on to more puppet play it will have proven merit enough. The bibliography appended is a far from complete list of puppet literature. It includes, however, the most important works of modern times upon mario- nettes and much comment, besides, that is casual or curious or close at hand. The author is under obligation to those friendly individuals who generously gave of their time and NOTE interest and whose suggestions, explanations and kind assistance have made possible this publication. -

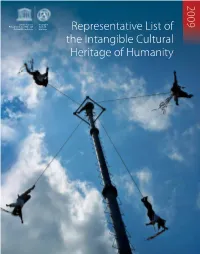

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Of

RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 2 2009 United Nations Intangible Educational, Scientific and Cultural Cultural Organization Heritage Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 5 Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 1 2009 Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 2 © UNESCO/Michel Ravassard Foreword by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO UNESCO is proud to launch this much-awaited series of publications devoted to three key components of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices. The publication of these first three books attests to the fact that the 2003 Convention has now reached the crucial operational phase. The successful implementation of this ground-breaking legal instrument remains one of UNESCO’s priority actions, and one to which I am firmly committed. In 2008, before my election as Director-General of UNESCO, I had the privilege of chairing one of the sessions of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, in Sofia, Bulgaria. This enriching experience reinforced my personal convictions regarding the significance of intangible cultural heritage, its fragility, and the urgent need to safeguard it for future generations. Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 3 It is most encouraging to note that since the adoption of the Convention in 2003, the term ‘intangible cultural heritage’ has become more familiar thanks largely to the efforts of UNESCO and its partners worldwide. -

Petrushka Show

Petrushka Show The Study Guide by Vancouver Puppet Theatre 2015 copyright © Contents The Company......................................................................# Set Up Requirements..........................................................# Background on the Production...........................................# Making the Show...............................................................# Synopsis of Petrushka Show..............................................# Discussion Topics..............................................................# Primary Students...............................................................# The Arts Curriculum.........................................................# Working with the Arts Community.....................................# Arts Education K to 7: At a Glance....................................# The Creative Process (Diagram) ..................................# Aknowledgement...................................................................# Dear Teacher: We’re looking forward to presenting Petrushka Show for your students. This Study Guide has a synopsis of the show, information about the production, and some background on the Vancouver Puppet Theatre. If you'd like to know more about our company, visit our website at www.vancouverpuppets.com We hope your students and staff enjoy the show! Kind Regards, Viktor Barkar Artistic Director and founder of the Vancouver Puppet Theatre Opportunities for listening, viewing, and responding to live and recorded performances and exhibitions are integral -

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity As Heritage Fund

ElemeNts iNsCriBed iN 2012 oN the UrGeNt saFeguarding List, the represeNtatiVe List iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL HERITAGe aNd the reGister oF Best saFeguarding praCtiCes What is it? UNESCo’s ROLe iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL SECRETARIAT Intangible cultural heritage includes practices, representations, Since its adoption by the 32nd session of the General Conference in HERITAGe FUNd oF THE CoNVeNTION expressions, knowledge and know-how that communities recognize 2003, the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural The Fund for the Safeguarding of the The List of elements of intangible cultural as part of their cultural heritage. Passed down from generation to Heritage has experienced an extremely rapid ratification, with over Intangible Cultural Heritage can contribute heritage is updated every year by the generation, it is constantly recreated by communities in response to 150 States Parties in the less than 10 years of its existence. In line with financially and technically to State Intangible Cultural Heritage Section. their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, the Convention’s primary objective – to safeguard intangible cultural safeguarding measures. If you would like If you would like to receive more information to participate, please send a contribution. about the 2003 Convention for the providing them with a sense of identity and continuity. heritage – the UNESCO Secretariat has devised a global capacity- Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural building strategy that helps states worldwide, first, to create