One of the Most Significant Aspects of Modernity As a Historical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste Représentative Du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel De L'humanité

Liste représentative du patrimoine culturel immatériel de l’humanité Date de Date récente proclamation Intitulé officiel Pays d’inscriptio Référence ou première n inscription Al-Ayyala, un art traditionnel du Oman - Émirats spectacle dans le Sultanat d’Oman et 2014 2014 01012 arabes unis aux Émirats arabes unis Al-Zajal, poésie déclamée ou chantée Liban 2014 2014 01000 L’art et le symbolisme traditionnels du kelaghayi, fabrication et port de foulards Azerbaïdjan 2014 2014 00669 en soie pour les femmes L’art traditionnel kazakh du dombra kuï Kazakhstan 2014 2014 00011 L’askiya, l’art de la plaisanterie Ouzbékistan 2014 2014 00011 Le baile chino Chili 2014 2014 00988 Bosnie- La broderie de Zmijanje 2014 2014 00990 Herzégovine Le cante alentejano, chant polyphonique Portugal 2014 2014 01007 de l’Alentejo (sud du Portugal) Le cercle de capoeira Brésil 2014 2014 00892 Le chant traditionnel Arirang dans la République 2014 2014 00914 République populaire démocratique de populaire Date de Date récente proclamation Intitulé officiel Pays d’inscriptio Référence ou première n inscription Corée démocratique de Corée Les chants populaires ví et giặm de Viet Nam 2014 2014 01008 Nghệ Tĩnh Connaissances et savoir-faire traditionnels liés à la fabrication des Kazakhstan - 2014 2014 00998 yourtes kirghizes et kazakhes (habitat Kirghizistan nomade des peuples turciques) La danse rituelle au tambour royal Burundi 2014 2014 00989 Ebru, l’art turc du papier marbré Turquie 2014 2014 00644 La fabrication artisanale traditionnelle d’ustensiles en laiton et en -

Türk Dünyası Öğrencilerinin Unesco Somut Olmayan Kültür Mirası

TÜRK DÜNYASI ÖĞRENCİLERİNİN UNESCO SOMUT OLMAYAN KÜLTÜR MİRASI DEĞERLERİNE İLİŞKİN BİLGİ VE DENEYİM DÜZEYLERİNİN KARŞILAŞTIRILMASI Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article Akkuş, Ç. (2020). Türk Dünyası Öğrencilerinin Geliş Tarihi: 21.07.2020 Unesco Somut Olmayan Kültür Mirası Değerlerine Kabul Tarihi: 20.12.2020 İlişkin Bilgi ve Deneyim Düzeylerinin E-ISSN: 2149-3871 Karşılaştırılması. Nevşehir Hacı Bektaş Veli Üniversitesi SBE Dergisi, 10(2), 608-624. DOI: 10.30783/nevsosbilen.772492 Çetin AKKUŞ Kastamonu Üniversitesi, Turizm Fakültesi, Turizm İşletmeciliği Bölümü [email protected] ORCID No: 0000-0002-6539-726X ÖZ Bu araştırmada Türk Cumhuriyetlerinden Türkiye’ye lisans öğrenimi amacıyla gelmiş üniversite öğrencilerinin kendi ülkelerinin UNESCO Somut Olmayan Kültürel Miras Listesi’nde yer alan kaynaklarına ilişkin bilgi ve deneyim düzeylerini tespit etmek amaçlanmıştır. Ayrıca listede bazı ortak değerleri tescillenen Türk Dünyası ülkeleri öğrencilerinin bu değerlere ilişkin bilgi ve deneyim düzeylerinin farklılığını saptamak hedeflenmiştir. Bu amaçla Kastamonu Üniversitesi’nde öğrenim gören Türkiye vatandaşı öğrenciler ile Azerbaycan, Kazakistan, Kırgızistan, Özbekistan ve Türkmenistan’dan gelen toplam 399 öğrenciye ulaşılmıştır. Ulaşılan verilere tanımlayıcı istatistikler ve farklılık analizleri yapılmıştır. Araştırma sonucunda en yüksek bilgi ve deneyim ortalamasına sahip ülke Kırgızistan olurken bunu sırasıyla Azerbaycan, Kazakistan, Türkmenistan, Türkiye, Özbekistan takip etmiştir. Kültürel miras değerleri içerisinde en bilinen unsurlar; Azerbaycan, Kazakistan ve Türkmenistan için Nevruz, Kırgızistan için Kırgız Destan Üçlemesi, Özbekistan için Özbek pilavı ve Türkiye için Karagöz olmuştur. Vatandaşları tarafından en az bilinen unsurlar ise; Azerbaycan için Çevgen oyunu, Kırgızistan için ekmek (lavaş, yufka) yapma kültürü, Kazakistan için Doğan- Şahinle avlanma, Özbekistan için Katta Ashula ve Boysun ilçesi kültürel alanı, Türkmenistan için Geleneksel Türk halı yapım sanatı ve son olarak Türkiye için Islık Dili ve Semah olmuştur. -

The Concept of Self and the Other

Tel Aviv University The Yolanda and David Katz Faculty of the Arts Department of Theatre Studies The Realm of the Other: Jesters, Gods, and Aliens in Shadowplay Thesis Submitted for the Degree of “Doctor of Philosophy” by Chu Fa Ching Ebert Submitted to the Senate of Tel Aviv University April 2004 This thesis was supervised by Prof. Jacob Raz TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF ILLUSTRATIONS................................................................................................vi INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................... 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... 7 I. THE CONCEPT OF SELF AND THE OTHER.................................................................... 10 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 11 The Multiple Self .................................................................................................................... 12 Reversal Theory...................................................................................................................... 13 Contextual Theory ................................................................................................................. 14 Self in Cross‐Cultural Perspective ‐ The Concept of Jen................................................... 17 Self .......................................................................................................................................... -

Asst. Prof. ÜMİT HARUN AKKAYA

Asst. Prof. ÜMİT HARUN AKKAYA OPfefricseo Pnhaol nIen:f +or9m0 3a5t2io 6n21 7982 Extension: 42816 EFmaxa iPl:h ohanreu:n +ak9k0a 0ya3@52k a6y2s1e r7i9.e9d0u .tr AWdedbr:e hstst:p sS:e/y/raavneis Kisa.kmapysüesrüi .eBdauh.çtre/liheavrleurn Makakha. yÇaevre Yolu Cad. İslami İlimler Fakültesi No:9 38400 Develi / KAYSERİ EDodcutocraatteio, Enr cIinyefso Urnmivaetrisoityn, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Philosophy and Religious Sciences, Turkey 2005 - 2016 UPonsdtegrrgardaudautaet, eE, rEcriyceiyse Us nUinveivresritsyit, yS,o İslayhaily Baitl iFmalkeürl tEenssi,t iFtüacsuül, tPyh oilfo Tshoepohlyo gayn,d T Rurekliegyio 1u9s9 S4c i-e 1n9ce9s9, Turkey 1999 - 2003 FEnogrliesihg, nB2 L Uapnpgeru Iangteersmediate Dissertations PDhoiclotosroapthey, A a nSdO CRIeOlLigOioGuYs OSFci eRnEcLeIsG, I2O0N1 6STUDY ON "MYSTERY SERIES", Erciyes University, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, KPoAsYtSgEraRdI,u Eartcei,y Ae sS TUUnDivYe rOsFit yS, OSCoIsOyLaOl BGiYli mOFle rR ELnIsGtiItOüNsü O, PNh MiloAsGoIpCh Ay NaDnd M RAeGliIgCioAuLs A SPcPieLnIcCeAsT, 2IO0N0S3 : A CASE STUDY IN RSoecsiael aSrcicehnc Aesr aenads Humanities, Theology, Sociology of Religion Academic Titles / Tasks Assistant Professor, YKoazygsaetr iB Uonziovke rUsnitiyv,e Drseivtye,l iF iasclaumltyi iOlimf Tlehre Foalokgüylt, e2s0i,1 F6e -ls 2e0fe1 9ve Din Bilimleri Bölümü , 2019 - Continues Academic and Administrative Experience -B Cöolünmtin Kuaelsite Komisyonu Üyesi, Kayseri University, Develi İslami İlimler Fakültesi, Felsefe Ve Din Bilimleri Bölümü , 2020 2B0ir1im9 -S Ctroantetijniku ePslan Komisyonu -

Mudyrd Munhal2019.Pdf

Kayseri İli Eğitim Kurumları Müdür Yardımcılığı Münhal Listesi S.No İlçe Adı Kodu Kurum Adı Münhal 1 AKKIŞLA 752374 Akkışla İmam Hatip Ortaokulu 1 2 AKKIŞLA 715468 Atatürk Ortaokulu 1 3 AKKIŞLA 715674 Derviş Çakırtekin Ortaokulu 1 4 AKKIŞLA 715995 Kululu Ortaokulu 1 5 AKKIŞLA 716155 Ortaköy Ortaokulu 1 6 AKKIŞLA 751586 Şehit Fikret Tunç Çok Programlı Anadolu Lisesi 1 7 BÜNYAN 700843 Atatürk İlkokulu 1 8 BÜNYAN 308309 Bünyan Mesleki ve Teknik Anadolu Lisesi 4 9 BÜNYAN 764076 Bünyan Sabancı Ögretmenevi ve Akşam Sanat okulu Müdürlüğü 1 10 BÜNYAN 170107 Bünyan Şehit Onur Karasungur Halk Eğitimi Merkezi 2 11 BÜNYAN 717097 Ekinciler Ortaokulu 1 12 BÜNYAN 700863 Fatih İlkokulu 1 13 BÜNYAN 751510 Güllüce İlkokulu 1 14 BÜNYAN 963201 Hamidiye Mesleki ve Teknik Anadolu Lisesi 2 15 BÜNYAN 717589 Köprübaşı Yakup Atila Ortaokulu 1 16 BÜNYAN 974311 Mehmet Alim Çınar Anaokulu 1 17 BÜNYAN 170097 Naci Baydemir Anadolu İmam Hatip Lisesi 1 18 BÜNYAN 955711 Şehit Jan. Onb. Abdi Altemel Çok Programlı Anadolu Lisesi 2 19 BÜNYAN 717998 Şehit Jandarma Er Zafer Akkaş Ortaokulu 1 20 BÜNYAN 868862 Şehit Piyade Teğmen Bekir Öztürk Çok Programlı Anadolu Lisesi 1 21 BÜNYAN 701124 Topsöğüt Ortaokulu 1 22 BÜNYAN 718148 Velioğlu Ortaokulu 1 23 DEVELİ 758363 Salih Onaran İmam Hatip Ortaokulu 1 24 DEVELİ 720615 İncesu Ortaokulu 1 25 DEVELİ 717319 Ayşepınar Ortaokulu 1 26 DEVELİ 763766 Bakırdağı Süleyman İlhan İmam Hatip Ortaokulu 1 27 DEVELİ 722422 Bakırdağı Süleyman İlhan Ortaokulu 1 28 DEVELİ 718048 Çaylıca Şehit Jandarma Er Zeki Özbek Ortaokulu 1 29 DEVELİ 748239 Develi -

Francesca Penoni-Thesis

ARMENIAN RELIGIOUS ARCHITECTURE IN THE LATE 19 th EARLY 20 th CENTURY KAYSERI: SPATIAL AND CULTURAL CLEANSING By FRANCESCA PENONI Submitted to the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History SABANCI UNIVERSITY January 2015 ARMENIAN RELIGIOUS ARCHITECTURE IN THE LATE 19 th EARLY 20 th CENTURY KAYSERI: SPATIAL AND CULTURAL CLEANSING APPROVED BY: Tülay Artan ………………………. (Thesis Advisor) Halil Berktay ……………………….. Hülya Adak ………………………… DATE OF APPROVAL: 05.01.2015 © Francesca Penoni 2015 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ARMENIAN RELIGIOUS ARCHITECTURE IN THE LATE 19 th EARLY 20 th CENTURY KAYSERI: SPATIAL AND CULTURAL CLEANSING Francesca Penoni History, M.A. Thesis, 2015 Thesis Advisor: Tülay Artan Keywords: Armenian religious architecture, Kayseri, Destruction This thesis is a study of the Ottoman Armenian religious architectural heritage in Kayseri and surrounding villages, with a particular focus on the destruction process that interested the Armenian churches and monasteries in the region. This study attempts to reconstruct the Armenian presence in the city center and the villages from mid- nineteenth century until 1915, through demographic make-up and main changes in the Armenian population of Kayseri. An investigation of the Armenian churches and monasteries built/rebuilt after the 1835 earthquake and the current conditions have been conducted through the creation of a catalogue. The thesis argues that the Armenian religious architecture of Kayseri and surroundings was targeted of spatial and cultural cleansing, as the removal or neglect process led to the vanishing/transformation of the majority of the analyzed architectural examples, including space-change and the end of the local Armenian culture. -

BİTKİ KORUMA ÜRÜNLERİ BAYİ LİSTESİ NO İlçesi Adı Soyadı Ticari Adı Adresi

BİTKİ KORUMA ÜRÜNLERİ BAYİ LİSTESİ NO İlçesi Adı Soyadı Ticari Adı Adresi Hamza SS.Kayseri Pancar Ekicileri Koop. Bünyan Pancar Ekicieri Koop. Cumhuriyet M. 1 Bünyan AKBABA Bünyan Satış Mağazası Alpaslan Türkeş C. No:50 Bünyan/KAYSERİ 2783 Sayılı B.Tuzhisar Tarım 2783 Sayılı B.tuzhisar T.K.K. Lale Mah. B.Tuzhisar 2 Bünyan Osman ÖZAY Kredi Kooperatifi Kasabası Bünyan/KAYSERİ Ömer 2664 Sayılı Akçatı Tarım Kredi 2264 Sayılı Akçatı Tarım Kredi Kop. No:52/A Akçatı 3 Bünyan SUNGUN Kooperatifi Köyü Bünyan/KAYSERİ Enes 4 Develi Yurtseven Tarım Hadibey Cad. No:77/A Develi/KAYSERİ YURTSEVEN Sofular Ticaret Boya ve Tarım 5 Develi Mahir SOLAK Melekgirmez Cad. No:96/A Develi/KAYSERİ İlaçları Remzi Ruşen Harman Mah. Cuma Büyükkılıç Pasajı 6 Develi Aykut Tarım İlaçları AYAN Develi/KAYSERİ Tevfik Hakan SS.Kayseri Pancar Ekicileri Koop. Develi Pancar Ekicileri Koop.Elbiz Cad. Sanayi Yolu 7 Develi KESKİN Develi Satış Mağazası Develi/KAYSERİ 2488 Sayılı Develi Tarım Kredi Hasan Şahan Mah. Cumhuriyet Caddesi 8 Develi Osman FINDIK Kooperatifi Develi/KAYSERİ Osman 879 Sayılı Ayşepınar Tarım Kredi 879 Sayılı Ayşepınar T.K.K. Ayşepınar Köyü 9 Develi SARIÇİÇEK Kooperatifi No:151/A Develi/KAYSERİ Gökhan 878 Sayılı Şahmelik Tarım Kredi 10 Develi Şahmelik Tarım Kredi Koop. Develi/KAYSERİ KILIÇKAYA Kooperatifi E.Camikebir Mah. Cumhuriyet Cad. No:81/B 11 Develi Timuçin ÜNLÜ YUŞA Tarım Develi/KAYSERİ Harun 1422 Sayılı Felahiye Tarım Kredi Felahiye Tarım Kredi Koop. Cumhuriyet Mah. 12 Felahiye ÇAMBUDAK Kooperatifi Atatürk Bulv. No:43 Felahiye/KAYSERİ 13 Hacılar Sami SARI Aşağı Mah. Çarşı Sok. No:8 Hacılar/KAYSERİ Karamustafapaşa Mah. -

List of the 90 Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage

Albania • Albanian Folk Iso-Polyphony (2005) Algeria • The Ahellil of Gourara (2005) Armenia • The Duduk and its Music (2005) Azerbaijan • Azerbaijani Mugham (2003) List of the 90 Masterpieces Bangladesh • Baul Songs (2005) of the Oral and Belgium • The Carnival of Binche (2003) Intangible Belgium, France Heritage of • Processional Giants and Dragons in Belgium and Humanity France (2005) proclaimed Belize, Guatemala, by UNESCO Honduras, Nicaragua • Language, Dance and Music of the Garifuna (2001) Benin, Nigeria and Tog o • The Oral Heritage of Gelede (2001) Bhutan • The Mask Dance of the Drums from Drametse (2005) Bolivia • The Carnival Oruro (2001) • The Andean Cosmovision of the Kallawaya (2003) Brazil • Oral and Graphic Expressions of the Wajapi (2003) • The Samba de Roda of Recôncavo of Bahia (2005) Bulgaria • The Bistritsa Babi – Archaic Polyphony, Dances and Rituals from the Shoplouk Region (2003) Cambodia • The Royal Ballet of Cambodia (2003) • Sbek Thom, Khmer Shadow Theatre (2005) Central African Republic • The Polyphonic Singing of the Aka Pygmies of Central Africa (2003) China • Kun Qu Opera (2001) • The Guqin and its Music (2003) • The Uyghur Muqam of Xinjiang (2005) Colombia • The Carnival of Barranquilla (2003) • The Cultural Space of Palenque de San Basilio (2005) Costa Rica • Oxherding and Oxcart Traditions in Costa Rica (2005) Côte d’Ivoire • The Gbofe of Afounkaha - the Music of the Transverse Trumps of the Tagbana Community (2001) Cuba • La Tumba Francesa (2003) Czech Republic • Slovácko Verbunk, Recruit Dances (2005) -

38.KYS.011 38.KYS.018 Sami Susam KAYSERİ ÇEVRE VE ŞEHİRCİLİK

KAYSERİ ÇEVRE VE ŞEHİRCİLİK İL MÜDÜRLÜĞÜNDEN KATI YAKIT SATICISI KAYIT BELGESİ ALAN SATICILARIN LİSTESİ KYS NO Firma Adres 1 38.KYS.001 Navruz Ticaret Yenidoğan Mah. Aslanağzı Sok. Kömürcüler Sit. No:8 Kocasinan/KAYSERĠ 2 38.KYS.002 Muratlar Enj. Bil. Mad.Gıda Teks. Nak. AmbTurz.San.Tic.Ltd.ġti Yenidoğan Mah. EmirĢah Sok.Kömürcüler Sit. No:8-9 Kocasinan/KAYSERĠ 3 38.KYS.003 Eğin Katı Yakıt Maddeleri Petr.ve Ağaç Ürn.Maden ĠnĢ.Turz.Tic.Ltd.ġti. Yenidoğan Mah.Kömürcüler Sit.Osmancık Cad. No:1 Kocasinan/KAYSERĠ 4 38.KYS.004 Aydınlar Hububat Odun Kömür ĠnĢ.Gıda Petr.Nakl.Teks.Elektr.San.Tic.Ltd.ġti. Yenidoğan Mah.EmirĢah Sok.Kömürcüler Sit. No:27 Kocasinan/KAYSERĠ 5 38.KYS.005 Aydınlar Ticaret Yenidoğan Mah.EmirĢah Sok.Kömürcüler Sit. No:26 Kocasinan/KAYSERĠ 6 38.KYS.007 Hattatlar Katı Yakıt San. ve Tic. Ltd.ġti. Yenidoğan Mah.Kömürcüler Sit.Palmiye Sok.No:1 Kocasinan/KAYSERĠ 7 38.KYS.008 Uhud Ticaret Yenidoğan Mah.Kömürcüler Sit.Osmancık Sok.No:52 Kocasinan/KAYSERĠ 8 38.KYS.009 Tekinler Hayv.Gıda ĠnĢ.Petr.Maden Teks. San. ve Tic. Ltd. ġti. Yenidoğan Mah.Kömürcüler Sit.Palmiye Sok.No:12 Kocasinan/KAYSERĠ 9 38.KYS.010 Kaplanlar Odun Kömür Sıvı Yakıt ĠnĢ.Turz.Nak. Tic. ve San. Ltd. ġti.. Yenidoğan Mah.Kömürcüler Sit.Osmancık Sok No:29-30 Kocasinan/KAYSERĠ Kılavuzlar Lokantacılık Odun Kömür ĠnĢ.Malz.Prof.Bina Yön. 10 38.KYS.011 Gavremoğlu Mah. Tavlusun Cad. No:21 Melikgazi/KAYSERĠ Doğalgaz Sist.Bilg. ve Bilg.Malz.Petr.Ürn.Nak.Turz.San. ve Tic.Ltd.ġti. -

Change in Precipitation and Temperature Amounts Over Three Decades in Central Anatolia, Turkey

Atmospheric and Climate Sciences, 2012, 2, 107-125 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/acs.2012.21013 Published Online January 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/acs) Change in Precipitation and Temperature Amounts over Three Decades in Central Anatolia, Turkey Türkan Bayer Altın, Belma Barak, Bekir Necati Altın Department of Primary School Teaching, Faculty of Education, Niğde University, Niğde, Turkey Email: [email protected] Received August 5, 2011; revised October 12, 2011; accepted November 19, 2011 ABSTRACT The study presents the change in precipitation and temperature of the Central Anatolia region which a semi-arid climate prevails. The climatic data consists of the monthly rainfall totals and temperatures from 33 stations in region for the period of 1975-2007. The spatial distribution, the inter-seasonal and the inter-annual amounts of rainfall were studied, along with the vulnerability of Central Anatolia to desertification processes and the place of this semiarid region. An- nual temperature frequency has been calculated and shows significant increase in temperature of approximately 2.6% corresponding to 0.4˚C. The change in climate was determined according to Erinç’s aridity index. Semi-arid and semi-humid climate types prevailed in Ürgüp, Kirikkale, Develi, Kirşehir and Akşehir between 1975 and 1990. How- ever, arid and semi-arid conditions prevailed in these stations after 1990. The decrease of the mean rainfall intensity (MRI) has varied between 0.3% and 21% annually since 1990. Decreases in seasonal rainfall intensity (SRI) and annual rainfall totals are found generally in the south, east and southeast of the region. Increases in SRI and annual rainfall to- tals are observed in the north and northwest of the region however, these increasing percentages are not as great as the decreasing percentages. -

Develi Raporu New.Pdf

ERMENI KÜLTÜR VARLIKLARIYLA DEVELİ DEVELI WITH ITS ARMENIAN CULTURAL HERITAGE Hrant Dink Vakfı, Hrant Dink’in, 19 Ocak 2007’de, Hrant Dink Foundation was established after the gazetesi Agos’un önünde öldürülmesinden sonra, benzer assasination of Hrant Dink in front of his newspaper Agos acıların yeniden yaşanmaması için; onun daha adil ve on January 19, 2007, in order to avoid similar pains and to özgür bir dünyaya yönelik hayallerini, dilini ve yüreğini continue Hrant Dink’s legacy, his language and heart and his yaşatmak amacıyla kuruldu. Etnik, dinî, kültürel ve cinsel dream of a world that is more free and just. Democracy and tüm farklılıklarıyla herkes için demokrasi ve insan hakları human rights for everyone regardless of their ethnic, religious talebi, vakfın temel ilkesidir. or cultural origin or gender is the Foundation’s main principle. Vakıf, ifade özgürlüğünün alabildiğine kullanıldığı, The Foundation works for a Turkey and a world where tüm farklılıkların teşvik edilip yaşandığı, yaşatıldığı ve freedom of expression is limitless and all differences are çoğaltıldığı, geçmişe ve günümüze bakışımızda vicdanın allowed, lived, appreciated, multiplied and conscience ağır bastığı bir Türkiye ve dünya için çalışır. Hrant Dink outweighs the way we look at today and the past. As the Vakfı olarak ‘uğruna yaşanası davamız’, diyalog, barış, Hrant Dink Foundation ‘our cause worth living’ is a future empati kültürünün hâkim olduğu bir gelecektir. where a culture of dialogue, peace and empathy prevails. ERMENİ KÜLTÜR VARLIKLARIYLA DEVELİ -

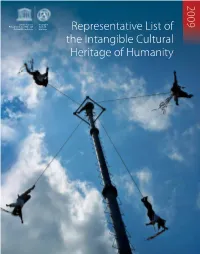

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Of

RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 2 2009 United Nations Intangible Educational, Scientific and Cultural Cultural Organization Heritage Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 5 Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 1 2009 Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 2 © UNESCO/Michel Ravassard Foreword by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO UNESCO is proud to launch this much-awaited series of publications devoted to three key components of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices. The publication of these first three books attests to the fact that the 2003 Convention has now reached the crucial operational phase. The successful implementation of this ground-breaking legal instrument remains one of UNESCO’s priority actions, and one to which I am firmly committed. In 2008, before my election as Director-General of UNESCO, I had the privilege of chairing one of the sessions of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, in Sofia, Bulgaria. This enriching experience reinforced my personal convictions regarding the significance of intangible cultural heritage, its fragility, and the urgent need to safeguard it for future generations. Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 3 It is most encouraging to note that since the adoption of the Convention in 2003, the term ‘intangible cultural heritage’ has become more familiar thanks largely to the efforts of UNESCO and its partners worldwide.