Baffin Island: Field Research and High Arctic Adventure, 1961-1967

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Penguins and Polar Bears Shapero Rare Books 93

OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS Shapero Rare Books 93 OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS EXPLORATION AT THE ENDS OF THE EARTH 32 Saint George Street London W1S 2EA +44 20 7493 0876 [email protected] shapero.com CONTENTS Antarctica 03 The Arctic 43 2 Shapero Rare Books ANTARCTIca Shapero Rare Books 3 1. AMUNDSEN, ROALD. The South Pole. An account of “Amundsen’s legendary dash to the Pole, which he reached the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the “Fram”, 1910-1912. before Scott’s ill-fated expedition by over a month. His John Murray, London, 1912. success over Scott was due to his highly disciplined dogsled teams, more accomplished skiers, a shorter distance to the A CORNERSTONE OF ANTARCTIC EXPLORATION; THE ACCOUNT OF THE Pole, better clothing and equipment, well planned supply FIRST EXPEDITION TO REACH THE SOUTH POLE. depots on the way, fortunate weather, and a modicum of luck”(Books on Ice). A handsomely produced book containing ten full-page photographic images not found in the Norwegian original, First English edition. 2 volumes, 8vo., xxxv, [i], 392; x, 449pp., 3 folding maps, folding plan, 138 photographic illustrations on 103 plates, original maroon and all full-page images being reproduced to a higher cloth gilt, vignettes to upper covers, top edges gilt, others uncut, usual fading standard. to spine flags, an excellent fresh example. Taurus 71; Rosove 9.A1; Books on Ice 7.1. £3,750 [ref: 96754] 4 Shapero Rare Books 2. [BELGIAN ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION]. Grande 3. BELLINGSHAUSEN, FABIAN G. VON. The Voyage of Fete Venitienne au Parc de 6 a 11 heurs du soir en faveur de Captain Bellingshausen to the Antarctic Seas 1819-1821. -

The Scott Inlet – Buchan Gulf Oil Seeps: Actively Venting Petroleum Systems on the Northern Baffin Margin Offshore Nunavut, Canada

The Scott Inlet – Buchan Gulf Oil Seeps: Actively venting petroleum systems on the northern Baffin Margin offshore Nunavut, Canada Gordon. N. Oakey1, Phil N. Moir1*, Tom Brent2, Kate Dickie1, Chris Jauer1, Robbie Bennett1, Graham Williams1, Brian MacLean1, Paul Budkewitsch4**, Jim Haggart3, Lisel Currie2 1 Geological Survey of Canada (Atlantic), 1 Challenger Drive, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada, B2Y 4A2 2 Geological Survey of Canada (Calgary) 3303-33rd St. NW, Calgary, Alberta, Canada,T2L 2A7 3 Geological Survey of Canada (Pacific) 625 Robson St., Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6B 5J3 4 Canada Centre for Remote Sensing, 588 Booth Street, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0Y7 * retired ** now with Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, PO Box 2000, Iqaluit, Canada, X0A 0H0 New analyses of legacy geophysical, geological and geochemical data have been integrated with modern multibeam bathymetry, RADARSAT imagery, and onshore geological mapping into a regional study of the petroleum system on the northern Baffin shelf offshore Nunavut. Industry seismic reflection profiles show that the Scott Inlet Graben is the southern end of an elongated basin (200-300 km by 25- 50 km wide) extending to the northwest along the Baffin Margin – now named Scott Inlet Basin – which contains up to 6 km of Mesozoic and Cenozoic strata. The seismic data define the outer edge of the Scott Inlet Basin; however, the landward edge is largely unknown and may locally outcrop onshore. Recent multibeam bathymetry data have been collected over the Scott Inlet Seep location as part of the ARCTICNET Research Program to study benthic habitats and geohazards in the Canadian Arctic waterways. -

The Quest for the Northwest Passage

NOVA DANIA THE QUEST FOR THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE SUZANNE CARLSON With considerable envy, the seventeenth century King of Denmark, Christian IV, watched the scramble to discover the elusive passage over Polar regions to lay claim to the riches of Cathay. This article will follow the fate of Christian’s early seventeenth century New World foothold, Nova Dania, through the cartographic record, speculating on what and when the Danes might have known about the then frozen northwest passage. An essential piece in this story is the amazing tale of Jens Munk, a merchant adventurer in the King’s service. For the cyber traveler, opportunities have reached a new zenith with Google Earth (FIGURE 1). I find myself cruising at 35,000 feet over the Alps, the Arabian Desert, up the Dania Nova Amazon, and to one of my favorite armchair destinations, FIGURE 2. JUSTUS DANCKERT’S TOTIUS AMERICAE DESCRIPTIO, the Arctic. With your AMSTERDAM, CA. 1680. VESTERGOTLANDS MUSEET, GOTHENBURG, SWEDEN Google joy stick, PART I - MAPPING NOVA DANIA you are able to glide with ease through the newly open waters With addictive zeal I searched map after map until I finally of the Northwest spotted it again: this time with the name reversed into Nova Passage. Dania (New Denmark). And there was more. Mer Cristian, Mare Christianum, or Christians Sea, depending on the Before the days of FIGURE 1. NORTHERN CANADA AND language appeared in what is now Fox Basin. Later, Nova GREENLAND. GOOGLE EARTH, 2006 satellite imaging, we Dania abandoned its Latin pretensions and became Nouvelle were content with and Denmarque and, as time went on, its location began to fascinated by maps, maps of unknown exotic places, maps wander—north into Buttons Bay, west into the interior, and showing nations or would-be empires. -

N National Museum of Natural History June 2002 Number 10

ewsletterewsletter Smithsonian Institution NN National Museum of Natural History June 2002www.mnh.si.edu/arctic Number 10 NOTES FROM THE DIRECTOR for the University of Maryland. Irwin Shapiro, Director of By Bill Fitzhugh the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, has been named Interim Under Secretary; and Douglas Erwin has been named In thirty two years at the Smithsonian, I have never Interim Director of NMNH while the search for a permanent experienced a year quite like the last one. In the past, the person for both positions continues. Yours Truly has become Smithsonian seemed immune from worldly upheavals, and Chair of Anthropology (a post I held from 1975-80). By this sailed steadily forward even in troubled times. During these time next year the Science Commission Report will have been years, the Institution changed physically and intellectually, on the table for six months, and I hope to report new directions increased the social and ethnic diversity of its staff and and improved prospects for Smithsonian science. programming, and began to diversify its funding stream; but the basic commitment to scholarship and research remained solid. *** Today, this foundation is being challenged as never before. The result has been an unusual year, to say the least. A Despite difficult times, the ASC has maintained its core stream of directors—seven or eight at last count—have left programs and has initiated new projects. At long last, Igor their posts; a special commission has investigated American Krupnik and I, with assistance from Elisabeth Ward, History’s exhibition program; a congressional science succeeded in realizing the dream of a dedicated ASC monograph commission is evaluating Smithsonian science; and two series. -

Polar Bears from Space: Assessing Satellite Imagery As a Tool to Track Arctic Wildlife

Polar Bears from Space: Assessing Satellite Imagery as a Tool to Track Arctic Wildlife Seth Stapleton1*¤a, Michelle LaRue3, Nicolas Lecomte4¤b, Stephen Atkinson4, David Garshelis2,5, Claire Porter3, Todd Atwood1 1 United States Geological Survey, Alaska Science Center, Anchorage, Alaska, United States of America, 2 Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Biology, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota, United States of America, 3 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America, 4 Department of Environment, Government of Nunavut, Igloolik, Nunavut, Canada, 5 Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Grand Rapids, Minnesota, United States of America Abstract Development of efficient techniques for monitoring wildlife is a priority in the Arctic, where the impacts of climate change are acute and remoteness and logistical constraints hinder access. We evaluated high resolution satellite imagery as a tool to track the distribution and abundance of polar bears. We examined satellite images of a small island in Foxe Basin, Canada, occupied by a high density of bears during the summer ice-free season. Bears were distinguished from other light-colored spots by comparing images collected on different dates. A sample of ground-truthed points demonstrated that we accurately classified bears. Independent observers reviewed images and a population estimate was obtained using mark– recapture models. This estimate (N^ : 94; 95% Confidence Interval: 92–105) was remarkably similar to an abundance estimate derived from a line transect aerial survey conducted a few days earlier (N^ : 102; 95% CI: 69–152). Our findings suggest that satellite imagery is a promising tool for monitoring polar bears on land, with implications for use with other Arctic wildlife. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Journal of a Voyage from Okkak : on the Coast Of

/ JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE FROM OKKAK, ON THE COAST OF LABRADOR, TO UNGAVA BAY, WESTWARD OF CAPE CIIUDLEIGH; UNDERTAKEN To explore the Coast, and visit the Esquimaux in that unknown Region, BENJAMIN KOHLMEISTER, AND GEORGE KMOCH, MISSIONARIES OF THE CHURCH OF THE UNITAS FRATRUM or UNITED BRETHREN flxmtron: Printed by W. M'Dowall, Pemberton Row, Gough Square, Fleet Street, FOR THE BRETHREN'S SOCIETY FOR THE FURTHERANCE OF THE GOSPEL AMONG THE HEATHEN. FEBVRE, CHAPEL-PLACE, NEVILS COURT, FETTF.R-LA NE AND SOLD BY J. LE 2, J L. B. 8EELEY, 169, FLEET-STREET; HAZARD AND BINNS, BATH*, AND T. BULGIN, AND T. LAMBE, BRISTOL. 1814. io \S. JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE, INTRODUCTION. FOR these many years past, a considerable number of Esquimaux have been in the annual practice of visiting the three missionary establishments of the United Brethren on the coast of Labrador, Okkak, Nain, and Hopedale, chiefly with a view to barter, or to see those of their friends and ac- quaintance, who had become obedient to the gospel, and lived together in Christian fellowship, enjoying the instruction of the Missionaries. These people came mostly from the north, and some of them from a great distance. They reported, that the body of the Esquimaux nation lived near and beyond Cape Chud- leigh, which they call Killinek, and having conceived much friendship for the Missionaries, never failed to request, that some of them would come to their country, and even urged the formation of a new settlement, considerably to the north of Okkak. To these repeated and earnest applications the Mission- aries were the more disposed to listen, as it had been disco- vered, not many years after the establishment of the Mission in 177 lj, that that part of the coast on which, by the encou- ragement of the British government, the first settlement was made, was very thinly inhabited, and that the aim of the Mission, to convert the Esquimaux to Christianity, would be . -

Stefan Glowacz on Baffin Island at the End of the World by Stefan Glowacz

Stefan Glowacz on Baffin Island At the End of the World By Stefan Glowacz and Tom Dauer May 15th 2008 Actually, we should have been content, happy even. For days we had been climbing on this wall that rose 700 meters from the ice. For days our world had been tilted vertical. For days we had laboured, suffered, feared and hoped. Until we had reached the highest point of the “Bastions”, a granite tower on the east coast of Baffin Island. The wind had lulled as we sat in the sun on the summit plateau. No human had been here before us. No one had yet looked out from here over the Buchan Gulf, over the Cambridge and the Quernbiter Fjord, and the Icy Arm. In the east, the flow edge marked the boundary between the ice pack and the open sea. And further out, beyond the Baffin Bay, lay Greenland. For more than an hour we enjoyed the view, the peace. Then we started to rappel down to base. Actually, a load should have fallen from our shoulders now. But Klaus Fengler, Holger Heuber, Mariusz Hoffmann, Robert Jasper and I knew very well that our lives would be depending on a shattering fundament. We had no more than 20 days to reach Clyde River, 350 kilometres away, each of us lugging a 75-kilogram pulka over melting ice. Four Weeks Earlier Looking out the window of the small Twin Otter, I felt like staring into a giant freezer and I realized that you can’t only feel the cold, but you can also see it. -

Glacial Morphology of the Cary Age Deposits in a Portion of Central Iowa John David Foster Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-1969 Glacial morphology of the Cary age deposits in a portion of central Iowa John David Foster Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Foster, John David, "Glacial morphology of the Cary age deposits in a portion of central Iowa" (1969). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 17570. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/17570 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GLACIAL MORPHOLOGY OF THE CARY AGE DEPOSITS IN A PORTION OF CENTRAL IOWA by John David Foster A Thesis Submitted to the . • Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major Subject: Geology Approved: Signatures have been redacted for privacy rs ity Ames, Iowa 1969 !/Y-J ii &EW TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT vii INTRODUCTION Location 2 Drainage 3 Geologic Description 3 Preglacial Topography 6 Pleistocene Stratigraphy 12 Acknowledgments . 16 GLACIAL GEOLOGY 18 General Description 18 Glacial Geology of the Study Area 18 Till Petrofabric Investigation 72 DISCUSSION 82 Introduction 82 Hypothetical Regime of the Cary Glacier 82 Review -

Baffin Island: Field Research and High Arctic Adventure, 1961-1967

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2016-02 Baffin Island: Field Research and High Arctic Adventure, 1961-1967 Ives, Jack D. University of Calgary Press Ives, J.D. "Baffin Island: Field Research and High Arctic Adventure, 1961-1967." Canadian history and environment series; no. 18. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2016. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/51093 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca BAFFIN ISLAND: Field Research and High Arctic Adventure, 1961–1967 by Jack D. Ives ISBN 978-1-55238-830-3 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

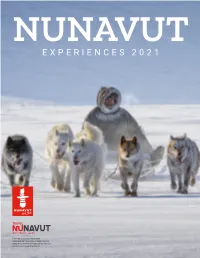

EXPERIENCES 2021 Table of Contents

NUNAVUT EXPERIENCES 2021 Table of Contents Arts & Culture Alianait Arts Festival Qaggiavuut! Toonik Tyme Festival Uasau Soap Nunavut Development Corporation Nunatta Sunakkutaangit Museum Malikkaat Carvings Nunavut Aqsarniit Hotel And Conference Centre Adventure Arctic Bay Adventures Adventure Canada Arctic Kingdom Bathurst Inlet Lodge Black Feather Eagle-Eye Tours The Great Canadian Travel Group Igloo Tourism & Outfitting Hakongak Outfitting Inukpak Outfitting North Winds Expeditions Parks Canada Arctic Wilderness Guiding and Outfitting Tikippugut Kool Runnings Quark Expeditions Nunavut Brewing Company Kivalliq Wildlife Adventures Inc. Illu B&B Eyos Expeditions Baffin Safari About Nunavut Airlines Canadian North Calm Air Travel Agents Far Horizons Anderson Vacations Top of the World Travel p uit O erat In ed Iᓇᓄᕗᑦ *denotes an n u q u ju Inuit operated nn tau ut Aula company About Nunavut Nunavut “Our Land” 2021 marks the 22nd anniversary of Nunavut becoming Canada’s newest territory. The word “Nunavut” means “Our Land” in Inuktut, the language of the Inuit, who represent 85 per cent of Nunavut’s resident’s. The creation of Nunavut as Canada’s third territory had its origins in a desire by Inuit got more say in their future. The first formal presentation of the idea – The Nunavut Proposal – was made to Ottawa in 1976. More than two decades later, in February 1999, Nunavut’s first 19 Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) were elected to a five year term. Shortly after, those MLAs chose one of their own, lawyer Paul Okalik, to be the first Premier. The resulting government is a public one; all may vote - Inuit and non-Inuit, but the outcomes reflect Inuit values. -

Wolf-Sightings on the Canadian Arctic Islands FRANK L

ARCTIC VOL. 48, NO.4 (DECEMBER 1995) P. 313–323 Wolf-Sightings on the Canadian Arctic Islands FRANK L. MILLER1 and FRANCES D. REINTJES1 (Received 6 April 1994; accepted in revised form 13 March 1995) ABSTRACT. A wolf-sighting questionnaire was sent to 201 arctic field researchers from many disciplines to solicit information on observations of wolves (Canis lupus spp.) made by field parties on Canadian Arctic Islands. Useable responses were obtained for 24 of the 25 years between 1967 and 1991. Respondents reported 373 observations, involving 1203 wolf-sightings. Of these, 688 wolves in 234 observations were judged to be different individuals; the remaining 515 wolf-sightings in 139 observations were believed to be repeated observations of 167 of those 688 wolves. The reported wolf-sightings were obtained from 1953 field-weeks spent on 18 of 36 Arctic Islands reported on: no wolves were seen on the other 18 islands during an additional 186 field-weeks. Airborne observers made 24% of all wolf-sightings, 266 wolves in 48 packs and 28 single wolves. Respondents reported seeing 572 different wolves in 118 separate packs and 116 single wolves. Pack sizes averaged 4.8 ± 0.28 SE and ranged from 2 to 15 wolves. Sixty-three wolf pups were seen in 16 packs, with a mean of 3.9 ± 2.24 SD and a range of 1–10 pups per pack. Most (81%) of the different wolves were seen on the Queen Elizabeth Islands. Respondents annually averaged 10.9 observations of wolves ·100 field-weeks-1 and saw on average 32.2 wolves·100 field-weeks-1· yr -1 between 1967 and 1991.