Special Issue3.7 MB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Australian Museum Foundation

western australian museum ANNUAL REPORT 2005-2006 Abominable Snowman chatting with friends. This creature was a standout feature at an exhibition staged by animatronics specialist John Cox: How to Make a Monster: The Art and Technology of Animatronics. Photograph: Norm Bailey. ABOUT THIS REPORT This Annual Report is available in PDF format on the Western Australian Museum website www.museum.wa.gov.au Copies are available on request in alternate formats. Copies are archived in the State Library of Western Australia, the National Library Canberra and in the Western Australian Museum Library located at the Collection and Research Centre, Welshpool. For enquiries, comments, or more information about staff or projects mentioned in this report, please visit the Western Australian Museum website or contact the Museum at the address below. Telephone 9212 3700. PUBLISHED BY THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986 49 Kew Streeet, Welshpool, Western Australia 6106 www.museum.wa.gov.au ISSNISSN 2204-61270083-8721 © Western Autralian Museum, 2006 Contents Letter of transmittal 1 COMPLIANCE REQUIREMENTS Message from the Minister 2 Highlights – Western Australian Museum 2005-06 3 Auditor’s opinion financial statements 39 The year in review – Chief Executive Officer 5 Certification of financial statements 40 MUSEUM AT A GLANCE 7 Notes to the financial statements 45 INTRODUCING THE Certification of performance indicators 73 8 WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM Key performance indicators 74 REPORT ON OPERATIONS THE WESTERN -

Partial Flora Survey Rottnest Island Golf Course

PARTIAL FLORA SURVEY ROTTNEST ISLAND GOLF COURSE Prepared by Marion Timms Commencing 1 st Fairway travelling to 2 nd – 11 th left hand side Family Botanical Name Common Name Mimosaceae Acacia rostellifera Summer scented wattle Dasypogonaceae Acanthocarpus preissii Prickle lily Apocynaceae Alyxia Buxifolia Dysentry bush Casuarinacea Casuarina obesa Swamp sheoak Cupressaceae Callitris preissii Rottnest Is. Pine Chenopodiaceae Halosarcia indica supsp. Bidens Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia blackiana Samphire Chenopodiaceae Threlkeldia diffusa Coast bonefruit Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia quinqueflora Beaded samphire Chenopodiaceae Suada australis Seablite Chenopodiaceae Atriplex isatidea Coast saltbush Poaceae Sporabolis virginicus Marine couch Myrtaceae Melaleuca lanceolata Rottnest Is. Teatree Pittosporaceae Pittosporum phylliraeoides Weeping pittosporum Poaceae Stipa flavescens Tussock grass 2nd – 11 th Fairway Family Botanical Name Common Name Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia quinqueflora Beaded samphire Chenopodiaceae Atriplex isatidea Coast saltbush Cyperaceae Gahnia trifida Coast sword sedge Pittosporaceae Pittosporum phyliraeoides Weeping pittosporum Myrtaceae Melaleuca lanceolata Rottnest Is. Teatree Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia blackiana Samphire Central drainage wetland commencing at Vietnam sign Family Botanical Name Common Name Chenopodiaceae Halosarcia halecnomoides Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia quinqueflora Beaded samphire Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia blackiana Samphire Poaceae Sporobolis virginicus Cyperaceae Gahnia Trifida Coast sword sedge -

Las Especies Del Género Alyogyne Alef. (Malvaceae, Malvoideae) Cultivadas En España

Las especies del género Alyogyne Alef. (Malvaceae, Malvoideae) cultivadas en España © 2008-2019 José Manuel Sánchez de Lorenzo-Cáceres www.arbolesornamentales.es El género Alyogyne Alef. comprende arbustos perennes, con indumento denso o de pelos esparcidos, con las hojas alternas, pecioladas, enteras, palmatilobadas o muy divididas, con estípulas diminutas y caedizas. Las flores son solitarias, axilares, sobre pedicelos largos y articulados. El epicáliz posee 4-10(-12) segmentos unidos en la base; el cáliz consta de 5 sépalos, más largos que el epicáliz, y la corola es más o menos acampanada, regular, formada por 5 pétalos obovados de color blan- co, rosa, lila o púrpura, adnatos a la base de la columna estaminal, cubiertos de pelos estrellados externamente. El androceo posee numerosos estambres (50-100) dispuestos en verticilos, con los filamentos unidos formando una columna que rodea al estilo, y las anteras uniloculares, dehiscentes por suturas longitudinales. El gineceo posee un ovario súpero, con 3-5 lóculos, cada uno de los cuales encierra 3-10 rudimentos seminales. Los estilos están unidos casi hasta el ápice, dividiéndose finalmente en 5 estigmas. El fruto es una cápsula dehis- cente por 3-5 valvas, conteniendo numerosas semillas (3-50) de pequeño tamaño, reniformes o globosas, glabras o pelosas. El nombre procede del griego alytos = unido y gyne = mujer, en alu- sión a los estilos unidos. Según Lewton (1915), el nombre debería ser Allogyne, del griego állos = otro, diferente y gyne = mujer, hembra, en alusión a la diferencia con Hibiscus en cuanto a los estilos. Realmente esta es la gran diferencia con el género Hibiscus, donde los estilos se separan por debajo de los estigmas, mientras que en Alyogyne están unidos justo hasta llegar a los estig- mas, momento en que se dividen. -

Acf Final Cs

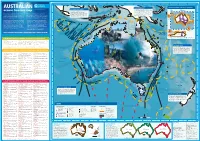

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P NORTH MARINE REGION AUSTRALIA’S OCEANS: FROM ASIA TO ANTARCTICA AUSTRALIAN www.acfonline.org.au/oceans 1 1 NORTH-WEST MARINE REGION The 700,000 square kilometres of this region cover the shallow waters of the Gulf of Carpentaria and the oceans treasure map The region’s one million square kilometres contain Arafura and Timor seas. Inshore ocean life is an extensive continental shelf, diverse and influenced by the mixing of freshwater runoff from productive coral reefs and some of the best examples Australia’s oceans are the third largest and most Without our oceans, Australia’s environment, tropical rainfall and wind and storm-driven surges of tropical and arid-zone mangroves in the world. of sea water. Many turtles, dugongs, dolphins and diverse on Earth. Three major oceans, five climate economy, society and culture would be very The breeding and feeding grounds for a number of seabirds travel through the area. threatened migratory species are found here along Christmas zones, varied underwater seascapes and mighty different. They are our lifestyle-support system. But Island currents bring together an amazing wealth of ocean they have suffered from our use and less than five 2 with large turtle and seabird populations. 2 Cocos treasures. This map shows you where to find them. per cent is free of fishing and offshore oil and gas. e Ara in fura C R Keeling r any eg a ons io Islands M n Tor Norfolk res rth Island Australia has the world’s largest area of coral reefs, To protect our ocean treasures Australia needs to: o Strait TIMOR N DARWIN Van Diemen Raine Island the largest single reef−the Great Barrier Reef−and • create a network of marine national parks free of SEA Rise Wessel the largest seagrass meadow in Shark Bay. -

Native Orchid Society South Australia

Journal of the Native Orchid Society of South Australia Inc Print Post Approved .Volume 37 Nº 8 PP 543662/00018 September 2013 NATIVE ORCHID SOCIETY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA PO BOX 565 UNLEY SA 5061 www.nossa.org.au. The Native Orchid Society of South Australia promotes the conservation of orchids through the preservation of natural habitat and through cultivation. Except with the documented official representation of the management committee, no person may represent the Society on any matter. All native orchids are protected in the wild; their collection without written Government permit is illegal. PRESIDENT SECRETARY Geoffrey Borg: John Bartram Email. [email protected] Email: [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT Kris Kopicki COMMITTEE Jan Adams Bob Bates Robert Lawrence Rosalie Lawrence EDITOR TREASURER David Hirst Gordon Ninnes 14 Beaverdale Avenue Telephone Windsor Gardens SA 5087 mob. Telephone 8261 7998 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] or [email protected] LIFE MEMBERS Mr R. Hargreaves† Mr. L. Nesbitt Mr H. Goldsack† Mr G. Carne Mr R. Robjohns† Mr R Bates Mr J. Simmons† Mr R Shooter Mr D. Wells† Mr W Dear Mrs C Houston Conservation Officer: Thelma Bridle / Bob Bates Field Trips Coordinator: Wendy Hudson. Ph: 8251 2762, Email: [email protected] Trading Table: Judy Penney Show Marshall: vacant Registrar of Judges: Les Nesbitt Tuber bank Coordinator: Jane Higgs ph. 8558 6247; email: [email protected] New Members Coordinator: Vacant PATRON Mr L. Nesbitt The Native Orchid Society of South Australia, while taking all due care, take no responsibility for loss or damage to any plants whether at shows, meetings or exhibits. -

Alyogyne Huegelii (Endl.) SCORE: -2.0 RATING: Low Risk Fryxell

TAXON: Alyogyne huegelii (Endl.) SCORE: -2.0 RATING: Low Risk Fryxell Taxon: Alyogyne huegelii (Endl.) Fryxell Family: Malvaceae Common Name(s): lilac hibiscus Synonym(s): Hibiscus huegelii var. wrayae (Lindl.) HibiscusBenth. wrayae Lindl. Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 3 May 2018 WRA Score: -2.0 Designation: L Rating: Low Risk Keywords: Shrub, Ornamental, Unarmed, Non-Toxic, Insect-Pollinated Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) Intermediate tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 n 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 401 Produces -

Evolution of the Iguanine Lizards (Sauria, Iguanidae) As Determined by Osteological and Myological Characters David F

Brigham Young University Science Bulletin, Biological Series Volume 12 | Number 3 Article 1 1-1971 Evolution of the iguanine lizards (Sauria, Iguanidae) as determined by osteological and myological characters David F. Avery Department of Biology, Southern Connecticut State College, New Haven, Connecticut Wilmer W. Tanner Department of Zoology, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byuscib Part of the Anatomy Commons, Botany Commons, Physiology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Avery, David F. and Tanner, Wilmer W. (1971) "Evolution of the iguanine lizards (Sauria, Iguanidae) as determined by osteological and myological characters," Brigham Young University Science Bulletin, Biological Series: Vol. 12 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byuscib/vol12/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brigham Young University Science Bulletin, Biological Series by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. S-^' Brigham Young University f?!AR12j97d Science Bulletin \ EVOLUTION OF THE IGUANINE LIZARDS (SAURIA, IGUANIDAE) AS DETERMINED BY OSTEOLOGICAL AND MYOLOGICAL CHARACTERS by David F. Avery and Wilmer W. Tanner BIOLOGICAL SERIES — VOLUME Xil, NUMBER 3 JANUARY 1971 Brigham Young University Science Bulletin -

APPENDIX D Biological Technical Report

APPENDIX D Biological Technical Report CarMax Auto Superstore EIR BIOLOGICAL TECHNICAL REPORT PROPOSED CARMAX AUTO SUPERSTORE PROJECT CITY OF OCEANSIDE, SAN DIEGO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: EnviroApplications, Inc. 2831 Camino del Rio South, Suite 214 San Diego, California 92108 Contact: Megan Hill 619-291-3636 Prepared by: 4629 Cass Street, #192 San Diego, California 92109 Contact: Melissa Busby 858-334-9507 September 29, 2020 Revised March 23, 2021 Biological Technical Report CarMax Auto Superstore TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 3 SECTION 1.0 – INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 6 1.1 Proposed Project Location .................................................................................... 6 1.2 Proposed Project Description ............................................................................... 6 SECTION 2.0 – METHODS AND SURVEY LIMITATIONS ............................................ 8 2.1 Background Research .......................................................................................... 8 2.2 General Biological Resources Survey .................................................................. 8 2.3 Jurisdictional Delineation ...................................................................................... 9 2.3.1 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Jurisdiction .................................................... 9 2.3.2 Regional Water Quality -

Reintroducing the Dingo: the Risk of Dingo Predation to Threatened Vertebrates of Western New South Wales

CSIRO PUBLISHING Wildlife Research http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/WR11128 Reintroducing the dingo: the risk of dingo predation to threatened vertebrates of western New South Wales B. L. Allen A,C and P. J. S. Fleming B AThe University of Queensland, School of Animal Studies, Gatton, Qld 4343, Australia. BVertebrate Pest Research Unit, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Orange Agricultural Institute, Forest Road, Orange, NSW 2800, Australia. CCorresponding author. Present address: Vertebrate Pest Research Unit, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Sulfide Street, Broken Hill, NSW 2880, Australia. Email: [email protected] Abstract Context. The reintroduction of dingoes into sheep-grazing areas south-east of the dingo barrier fence has been suggested as a mechanism to suppress fox and feral-cat impacts. Using the Western Division of New South Wales as a case study, Dickman et al. (2009) recently assessed the risk of fox and cat predation to extant threatened species and concluded that reintroducing dingoes into the area would have positive effects for most of the threatened vertebrates there, aiding their recovery through trophic cascade effects. However, they did not formally assess the risk of dingo predation to the same threatened species. Aims. To assess the risk of dingo predation to the extant and locally extinct threatened vertebrates of western New South Wales using methods amenable to comparison with Dickman et al. (2009). Methods. The predation-risk assessment method used in Dickman et al. (2009) for foxes and cats was applied here to dingoes, with minor modification to accommodate the dietary differences of dingoes. This method is based on six independent biological attributes, primarily reflective of potential vulnerability characteristics of the prey. -

Chapter 1 Pre-Settlement

¢¢CHAPTER 1 PRE-SETTLEMENT The Aborigines1 are believed to have been on the South Coast of New South Wales for at least 20,000 years, judging from dating of carbon found in a cave near Burrill Lake. It is hard to get such a number of years into perspective. A thousand generations? A hundred times the duration of white settlement? We are not used to such scales of time. It is short as geologists measure time, but it is long enough to include the peak of the most recent ice age, when sea levels were lower by up to 100 metres. The shore would have been further east, and Brush Island not an island at all, for much of this time. Few legacies of the Aborigines remain.2 Murramarang headland has a large midden which was found by anthropologists from the Australian Museum in the 1920s, and from which many artefacts were collected. At that time, the midden area was bare, with shifting sand dunes that would cover or expose parts of it, so on each visit you could expect to see something new. The present vegetation is recent, and the result of deliberate efforts to ‘stabilise’ the dunes.3 1 Today, the term Aborigine is rarely used, having been replaced by ‘Aboriginal people’ or ‘Indigenous people/communities’ (A.G. and S.F.). 2 Many legacies of traditional Aboriginal use and occupation of the area still remain. The area has numerous recorded archaeological sites, and one of the best known is the large midden on Murramarang headland (see previous section). -

Third South Pacific Natiohal Parks & Reserves Conference

X ffi tI + I) )' THIRD SOUTH PACIFIC NATIOHAL PARKS & RESERVES CONFERENCE CONFERENGE REFORT - VOLUME 3 COUNTRY HEVIEWS x @,Copyrig,ht South Pacifio GonrmisslEn; 1 986, Atlrightsresened. No partotthispublicallon maybe repr,oduced in anyformorbyany pr'og€8s, whether for sale, profi[ mat€rlal gain, or frue dlstrlbution bltnout wittten pembelon. lneFd,tlos $rould be'di:rocted to the pubtishGr. Origlnaltext Engllsh. Pi€psrgrt for publicrtion at Sorith Paclflc Gofimiadon headguarterai Nournea; Ngw Gatedonla and printed at Universal Prlnt, t&AO i!,orne Stieet, Wdlingtcini lrlew E@lgnd, "Flep-ri'ntBd July 1 987" REPORT OF THE THIRD SOUTH PACIFIC NATIONAL PARKS AND RESERVES CONFERENCE HELD IN APIA, WESTERN SAMOA, 1985 VOLUME III COUNTRY REVIEIT/S 1. FOREWORI) The ThLrd South Paciflc Natlonal" Parks and Reserves Conference was held ln Apla, Western Sanoa, 24 - 3 July 1985 and as lcs title luplles it was the thlrd ln a serl€s rof regular meetLngs of Paclfic countrles on the issues of protected areas and coneervatlon. The earl.ler conferences were held ln New Zealand and Australia l-n 1975 and 1979 respectlvely. The prlnclpal obJectlve of the Conference r/as to pronoEe the conservation of nature ln the South PacLfic Region by raislng awareness of its lnpor- tance and by encouraglng governments to protect and manage both their terrestrial and narine ecosystems. The theme of tradltlonal conservatlon knowledge and practlces was central to the Conference. Other thernes covered lncLuded legal, admlnlstrattve and regJ.onal issues; marlne and coastal issues; training and tourlsm and resource and park management. The Conference was organlsed by the South Paclflc Regional Envlronment Programe (SPREP) of the South Paciflc Comlsslon (SpC) in conJunctlon with the Governmeot of Western Samoa, and the International Unlon for the Consenratl.on of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). -

Draft Survey Guidelines for Australia's Threatened Orchids

SURVEY GUIDELINES FOR AUSTRALIA’S THREATENED ORCHIDS GUIDELINES FOR DETECTING ORCHIDS LISTED AS ‘THREATENED’ UNDER THE ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION AND BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION ACT 1999 0 Authorship and acknowledgements A number of experts have shared their knowledge and experience for the purpose of preparing these guidelines, including Allanna Chant (Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife), Allison Woolley (Tasmanian Department of Primary Industry, Parks, Water and Environment), Andrew Brown (Western Australian Department of Environment and Conservation), Annabel Wheeler (Australian Biological Resources Study, Australian Department of the Environment), Anne Harris (Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife), David T. Liddle (Northern Territory Department of Land Resource Management, and Top End Native Plant Society), Doug Bickerton (South Australian Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources), John Briggs (New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage), Luke Johnston (Australian Capital Territory Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate), Sophie Petit (School of Natural and Built Environments, University of South Australia), Melanie Smith (Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife), Oisín Sweeney (South Australian Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources), Richard Schahinger (Tasmanian Department of Primary Industry, Parks, Water and Environment). Disclaimer The views and opinions contained in this document are not necessarily those of the Australian Government. The contents of this document have been compiled using a range of source materials and while reasonable care has been taken in its compilation, the Australian Government does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this document and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of the document.