Dressing for Carnival in Fernando Trueba's "Belle Époque" (1992) Chad M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

Representaciones Realistas De Niños, Adolescentes Y Jóvenes Marginales En El Cine Iberoamericano (1990-2003)

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LINGÜÍSTICA, LENGUAS MODERNAS, LÓGICA Y FILOSOFÍA DE LA CIENCIA, TEORÍA DE LA LITERATURA Y LITERATURA COMPARADA PROGRAMA DE DOCTORADO EN HISTORIA DEL CINE Representaciones realistas de niños, adolescentes y jóvenes marginales en el cine iberoamericano (1990-2003) TESIS DOCTORAL Presentada por: Juan Carlos Vargas Maldonado Director: Dr. Alberto Elena Díaz Madrid, junio de 2008 2 ÍNDICE Introducción 3 1. Las primeras búsquedas “realistas” en el cine 8 1.1 El realismo socialista 11 1.2 El documental etnográfico 13 1.3 El documental social 16 1.4 El realismo poético francés 17 1.5 Dos antecedentes realistas del cine de ficción mexicano y español 19 1.6 El neorrealismo italiano 23 1.7 Ejemplos prototípicos: El Limpiabotas y La tierra tiembla 27 2. Los olvidados: modelo paradigmático sobre los niños, adolescentes y 33 jóvenes marginales 3. La herencia del neorrealismo en las cinematografías venezolana, 42 brasileña, argentina, española, chilena, boliviana y colombiana (1950-1981) 3.1 Venezuela: La escalinata y Soy un delincuente 46 3.2 Brasil: Río 40 grados y Pixote, los olvidados de Dios 54 3.3 Argentina: Tire dié, Crónica de un niño solo y La Raulito 65 3.4 España: Los golfos y Deprisa, deprisa 77 3.5 Chile: Largo viaje y Valparaíso, mi amor 86 3.6 Bolivia: Chuquiago 93 3.7 Colombia: Gamín 97 4. Representaciones realistas 1990-2003 105 4.1 Delincuencia y crimen: Caluga o menta (Chile/España), Lolo (México), 108 Como nacen los ángeles (Brasil) y Ciudad de Dios (Brasil/Francia/Alemania), Pizza, birra, faso (Argentina), Barrio (España/Francia) y Ratas, ratones y rateros (Ecuador/Estados Unidos) 4.2 Sicarios: Sicario (Venezuela) y La virgen de los sicarios 155 (Colombia/España/Francia) 4.3 Niños de la calle: La vendedora de rosas (Colombia), Huelepega, 170 ley de la calle (Venezuela/España), De la calle (México) y El Polaquito (Argentina/España) 5. -

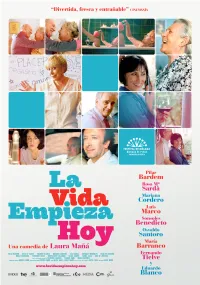

Dossier Completo

La vida empieza hoy Tienen experiencia, tienen ganas de hacer cosas, tienen una vida sexual activa… Y sobre todo... Tienen tiempo!!! SINOPSIS Un grupo de hombres y mujeres de la tercera edad asiste a clases de sexo para continuar teniendo una vida sexual plena. En ellas comparten deseos y preocupaciones. Pepe, tiene disfunción eréctil provocada por el estrés de la jubilación y quiere volver a ser el hombre que era; Herminia cree que es frígida pero descubre que su problema ha sido estar siempre con el hombre equivocado. A Julián le gustan las mujeres y sobre todo Herminia. Ambos se entienden tan bien en la cama, que deciden emprender una relación puramente sexual; Juanita tiene la certeza de que se va a morir, pero cuando se separa de su difunto marido, decide rehacer su vida... En la clase de sexo, Olga, la profesora, les ayuda a hacer frente a esos problemillas generados por la edad. Pero para eso, tendrán que hacer los deberes... Una historia coral, narrada en tono de comedia en la que padres, hijos y nietos se cruzan continuamente en una gran ciudad donde les resulta difícil encontrar su lugar. La vida empieza hoy FICHA ARTÍSTICA PILAR BARDEM Juanita ROSA Mª SARDÁ Olga MARIANA CORDERO Rosita LLUÍS MARCO Pepe SONSOLES BENEDICTO Herminia OSVALDO SANTORO Julián MARÍA BARRANCO Nina FERNANDO TIELVE Kim MONTSERRAT SALVADOR Carmen SÍLVIA SABATÉ Nuria ISABEL OSCA Mercedes ANA Mª VENTURA Adelita Y EDUARDO BLANCO Alfredo Con la colaboración especial de FRANCESC GARRIDO FERRÁN RAÑÉ MARC MARTÍNEZ La vida empieza hoy FICHA TÉCNICA DIRECTORA LAURA MAÑÁ GUIÓN ALICIA LUNA y LAURA MAÑÁ Basado en una idea original de ALICIA LUNA PRODUCTOR EJECUTIVO QUIQUE CAMÍN PRODUCTOR DELEGADO ANTONI CAMÍN DIRECTOR DE FOTOGRAFÍA MARIO MONTERO MONTAJE LUCAS NOLLA MÚSICA XAVIER CAPELLAS DIRECTOR DE ARTE BALTER GALLART DIRECTORA DE PRODUCCIÓN BET PUJOL SONIDO DANI FONTRODONA JEFE DE PRODUCCIÓN VALENTÍ CLOSAS FIGURINISTA MARÍA GIL MAQUILLAJE MONTSE BOQUERAS PELUQUERÍA SERGIO PÉREZ REPARTO LAURA CEPEDA MAKING OF JAVIER CALVO Formato y Duración 35mm (rodada en HD), Color, 90 min. -

Course FB-20 the IMAGE of SPAIN on the CINEMA SCREEN (ADVANCED LEVEL) (45 Class Hours) Lecturer: Dr. Luis Navarrete Cardero

Course FB-20 THE IMAGE OF SPAIN ON THE CINEMA SCREEN (ADVANCED LEVEL) (45 class hours) Lecturer: Dr. Luis Navarrete Cardero ([email protected]) Substitute Lecturer: Juan José Vargas Iglesias ([email protected]) OBJECTIVES This Course provides students with a route-map through those Spanish movies, as well as those from other countries, which deal with the image of Spain from different perspectives. There have been times when that same image has become distorted for reasons which are not, strictly speaking, cinematographic in character. Bringing to the fore the key aspects of that distortion, while analyzing a range of discourse types in film, can help to bring into focus the role of Cinema as a generator of cultural stereotypes. Keeping visiting students in mind, this Course spans a wide range of cultural perspectives, thus taking it beyond the confines of the cinematic and the historical sensu stricto. METHODOLOGY Given the amount of accumulated pedagogical experience that exists with regard to this kind of subject matter, as well as taking into account the specific needs of students, the aim of the class sessions is to ensure the fruitful interaction of the theoretical and practical dimensions of the study process, while also potentializing the exploration of those aspects of the Spanish language to which, in terms of comprehension and expression, the filmography being studied draws attention. SYLLABUS Practical Section Anthology of sequences taken from key movies and from the work of key directors: Escenas Españolas Lumiére. Sangre y Arena (Fred Niblo, 1922). Carmen (Cecil B. Demille, 1915). Carmen Burlesque (Charles Chaplin, 1916). -

Kinenova © 2020 Kinenova © 2020

KINENOVA © 2020 KINENOVA © 2020 В И Г О П Р Е Т С Т А В У В А В И Г О П Р Е Т С Т А В У В А KINENOVA © 2020 #ПРВОФИЛМ #KINENOVA2020 Е К С К Л У З И В Н О Н А 1-7 окт. 2020 1-7 Oct. 2020 КИНЕНОВА РЕТРО | | KINENOVA RETRO 8-18 окт. 2020 8-18 Oct. 2020 МЕЃУНАРОДНА КОНКУРЕНЦИЈА | | INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION ГЛАВНА НАТПРЕВАРУВАЧКА ПРОГРАМА 12-30 окт. 2020 12-30 Oct. 2020 ПОСВЕТЕНО НА ФЕРНАНДО ТРУЕБА | | DEDICATED TO FERNANDO TRUEBA Ја славиме шпанската култура Celebration of Spanish culture 26-28 окт. 2020 26-28 Oct. 2020 ФОКУС НА АВСТРИЈА | | FOCUS ON AUSTRIA 11-18 окт. 2020 11-18 Oct. 2020 КИНЕНОВА СПЕЦИЈАЛ | | KINENOVA SPECIAL 10-15 окт. 2020 10-15 Oct. 2020 LUX PRIZE | | LUX PRIZE НАГРАДА LUX НА ЕВРОПСКИОТ ПАРЛАМЕНТ LUX PRIZE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 10 окт. 2020 10 Oct. 2020 КИНЕНОВА НЕЗАВИСНИ & ВОН КОНКУРЕНЦИЈА | | KINENOVA INDEPENDENT & OUT OF COMPETITION 11-15 окт. 2020 11-15 Oct. 2020 ПОСВЕТЕНО НА БИЛЈАНА ГАРВАНЛИЕВА | | DEDICATED TO BILJANA GARVANLIEVA 19 окт. 2020 19 Oct. 2020 ОФИЦИЈАЛНА СЕЛЕКЦИЈА НА МАКЕДОНСКИ КУСИ ФИЛМОВИ 2020 | | OFFICIAL MACEDONIAN SHORT FILM COMPETITION 2020 19-23 окт. 2020 19-23 Oct. 2020 ОФИЦИЈАЛНА ИНТЕРНАЦИОНАЛНА СЕЛЕКЦИЈА | OFFICIAL INTERNATIONAL SHORT FILM НА КУСИ ФИЛМОВИ 2020 | COMPETITION 2020 13-15 окт. 2020 13-15 Oct. 2020 ПРОЕКЦИИ ВО ЖИВО ВО | LIVE SCREENINGS AT КИНОТЕКА НА СЕВЕРНА МАКЕДОНИЈА | KINOTEKA OF NORTH MACEDONIA — НЕБОЈША ЈОВАНОВИЌ — NEBOJSHA JOVANOVIK Директор на Меѓународен филмски фестивал Director of the International Film Festival of debutant на дебитантски филм „КинеНова“ lm “KineNova” Кон јубилејното, петто издание на Towards the fth jubilee edition of „КинеНова“ “KineNova” Ако на човека му ја одземеш можноста за креација, If you take away from someone the possibility to create, се чини како да си му одземал сè. -

Regreso Al Mediterráneo En La Cinematografía De Bigas Luna

ABSTRACT Regreso al This article approaches two films by Bigas Luna, Bambola and Son de mar (Sound of mediterráneo the Sea), produced after the Iberian trilogy −Jamón jamón, Huevos de oro (Golden en la Balls) y La teta y la luna (The Tit and The Moon)− catapulted him to worldwide cinematografía fame. It seems that the Catalan director wanted to combine erotic stories set in the de Bigas Luna same Mediterranean environment. Carolina Sanabria * KEYWORDS Bigas Luna, erotism, death, sexuality, adaptation, Bambola and Son de Mar RESUMEN (Sound of the Sea) El artículo pretende un acercamiento a dos de los filmes de Bigas Luna, Bambola y Son de mar, producidos luego de que la INTRODUCCIÓN trilogía ibérica (Jamón jamón, Huevos de oro y La teta y la luna) lo catapultara a A pesar de la irrecusable distancia nivel internacional. Parece que el director –en contenido y en espacio catalán quiso combinar historias de com- temporal– que los separa, dos de APORTES ponente erótico ambientadas en el mismo los filmes más eróticos del director entorno del Mediterráneo. catalán Bigas Luna, Bambola y Son de mar, parecen estar unificados por una voluntad de recuperación PALABRAS CLAVE del espíritu de la trilogía ibérica Bigas Luna – erotismo – muerte – sexuali- dad – adaptación – Bambola – Son de mar –en tanto comparten no sólo la obsesividad de sus personajes (desde distintas maneras) por la mujer, sino la sensualidad y la ambientación mediterráneas–. * Doctora en Comunicación Audiovisual y Publicidad por la Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona. Profesora de la Escuela de Estudios Generales de la Universidad La bella y la bestia de Costa Rica. -

Eurimages Co-Production La Grande Bellezza Wins Academy Award® for Best Foreign Language Film

T +33(0)388412560 www.coe.int [email protected] Ref. DC 026(2014) Eurimages co-production La Grande Bellezza wins Academy Award® for best foreign language film Strasbourg, 03.03.2014 - La Grande Bellezza (The Great Beauty) received the Oscar® for Best Foreign Language Film at Sunday’s Academy Awards® ceremony in Hollywood. Paolo Sorrentino’s film, a co-production between Italy and France supported by the Council of Europe’s fund Eurimages, has already won a European Film Award, a Golden Globe and a BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television Arts), and premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. Commenting on the prestigious award, Council of Europe Deputy Secretary General, Gabriella Battaini Dragoni said: “The Oscar for La Grande Bellezza highlights the strength and the relevance of international co-operation in the European film industry. It is a demonstration of the value of film co- production to our Continent”. Two other co-produced films, also supported by Eurimages, figured in this year’s list of nominations for the Academy Awards®: The Hunt (Denmark-Sweden) and The Broken Circle Breakdown (Belgium- The Netherlands). Since it was set up in 1988, EURIMAGES has supported 1,560 European co-productions for a total amount of approximately 474 million euros. Eight films have received the Oscar®: Journey of Hope, Xavier Koller; Belle Epoque, Fernando Trueba; Antonia’s Line, Marleen Gorris; Kolya, Jan Sverak; No Man’s Land, Danis Tanovic; Mar Adentro, Alejandro Amenabar; Amour, Michael Haneke; La Grande Bellezza, Paolo Sorrentino. * * * Eurimages is the cultural support fund of the Council of Europe. -

Publications Editor Prized Program Contributors Tribute Curator

THE NATIONAL FILM PRESERVE LTD. presents the Julie Huntsinger Directors Tom Luddy Gary Meyer Michael Ondaatje Guest Director Muffy Deslaurier Director of Support Services Brandt Garber Production Manager Bonnie Luftig Events Manager Bärbel Hacke Hosts Manager Shannon Mitchell Public Relations Manager Marc McDonald Theatre Operations Manager Lucy Lerner ShowCorps Manager Erica Gioga Housing/Travel Manager Kate Sibley Education Programs Dean Elizabeth Temple V.P., Filmanthropy Melissa DeMicco Development Manager Kirsten Laursen Executive Assistant to the Directors Technical Direction Russell Allen Sound, Digital Cinema Jon Busch Projection Chapin Cutler Operations Ross Krantz Chief Technician Jim Bedford Technical Coordinator Annette Insdorf Moderator Pierre Rissient Resident Curators Peter Sellars Paolo Cherchi Usai Godfrey Reggio Publications Editor Jason Silverman (JS) Prized Program Contributors Larry Gross (LG), Lead Writer Sheerly Avni (SA), Serge Bromberg (SB), Meredith Brody (MB), Paolo Cherchi Usai (PCU), Jesse Dubus (JD), Roger Ebert (RE), Scott Foundas (SF), Kirk Honeycutt (KH), Tom Luddy (TL), Jonathan Marlow (JM), Greil Marcus (GM), Gary Meyer (GaM), Michael Ondaatje (MO), Milos Stehlik (MS) Tribute Curator Chris Robinson 1 Shows The National Film Preserve, Ltd. A Colorado 501(c)(3) non-profit, tax-exempt educational corporation 1a S/Fri 6:30 PM - G/Sat 9:30 AM - 1b L/Sun 6:45 PM Founded in 1974 by James Card, Tom Luddy and Bill & Stella Pence 1 A Tribute to Peter Weir Directors Emeriti Bill & Stella Pence Board of Governors Peter Becker, Ken Burns, Peggy Curran, Michael Fitzgerald, Julie Huntsinger, Linda Lichter, Tom Luddy, Gary Meyer, Elizabeth Redleaf, Milos Stehlik, Shelton g. Stanfill (Chair), Joseph Steinberg, Linda C. -

Participación Española En Los Premios Oscar De Hollywood, Concedidos Por the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences - EE.UU./USA (1927-2020)

Participación española en los Premios Oscar de Hollywood, concedidos por The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences - EE.UU./USA (1927-2020) Nota: El año puede variar según se considere, así la 92ª edición celebrada en 2020 correspondería a los premios 2019. 2020 (93ª. Edición): El Agente Topo / The Mole Agent. Nominación: Documentary - Feature (Largometraje documental). Dirección: Maite Alberdi. País: España, Alemania, Países Bajos, Chile, Estados Unidos. La madre del blues / Ma Rainey's Black Bottom. Nominación: Makeup and Hairstyling (Maquillaje y Peluquería). Sergio López-Rivera, Mia Neal, Jamika Wilson. Dirección: George C. Wolfe. País: Estados Unidos. El magnífico Iván / The One And Only Ivan. Nominación: Visual Effects (Efectos visuales). Nick Davis, Greg Fisher, Ben Jones, Santiago Colomo Martínez. Dirección: Thea Sharrock. País: Estados Unidos. 2019 (92ª. Edición): Dolor y Gloria. Nominación: Actor in a Leading Role (Actor principal), Antonio Banderas. Nominación: International Feature Film (Largometraje internacional), por España. Dirección: Pedro Almodóvar. País: España. Klaus. Nominación: Animated Feature Film (Largometraje de animación). Dirección: Sergio Pablos. País: España. 2018 (91ª. Edición): Madre. Nominación: Best Live Action Short Film (Mejor cortometraje de ficción). Dirección: Rodrigo Sorogoyen. País: España. © Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte 2017 (90ª. Edición): Una mujer fantástica. Oscar a la Mejor película de habla no inglesa/Best Foreign Language Film ; por Chile. Dirección: Sebastián Lelio. País: España / Chile / Alemania. 2016 (89ª. Edición): Timecode. Nominación: Best Live Action Short Film (Mejor cortometraje de ficción). Dirección: Juanjo Giménez. País: España. Oscar técnico en la categoría Premio Científico y de Ingeniería. Marcos Fajardo. (Creador del programa “Arnold” para efectos digitales). 2015 (88ª. -

Film Festival Program

Celebrating New Cinema from Ibero- America and Spain at Central Michigan University Hosted by the Spanish Program of the Department of World Languages and Cultures February 22 - April 26, 2021 Streaming platform: https://pragda.com/sfc-event/central-michigan-university/ The film Monos will be screened by Chipcast-PANOPTO from Pearce Hall 127, Central Michigan University, Mt. Pleasant, Michigan 48859 The Spanish Film Club series was made possible with the support of: Pragda Org., SPAIN Arts & Culture, and the Secretary of State for Culture of Spain. In collaboration with and generous support of CMU’s College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of World Languages and Cultures Department of Political Science Honors Program Office of Global Engagement Office of Institutional Diversity Equity & Inclusion Office of Student Activities and Involvement / Program Board PERRO BOMBA (Bombshell Dog) STREAMING ACCESS WEEK: February 22-28 Dir. JUAN CÁCERES / Chile, France / 80 min / 2019 Spanish and Creole with English subtitles https://pragda.com/film/perro-bomba/?sfc=1 With Steevens Benjamin, Alfredo Castro, Blanca Lewin, Gastón Salgado, Junior Valcin, Erto Pantoja, Daniel Antivilo Film Synopsis: Steevens is a young Haitian immigrant living a challenging, but somewhat stable life in Santiago de Chile: he has a construction job, a home, friends, and fun. This precariously balanced life is disrupted when Junior, a childhood friend from Haiti, arrives in Chile seeking assistance from Steevens to establish himself. Junior has entered Chile without papers and doesn’t speak any Spanish. Steevens does everything he can to support his friend and even manages to get him a job with his employer. -

English Language Spanish Films Since the 1990S

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 33 Issue 2 Identities on the Verge of a Nervous Article 8 Breakdown: The Case of Spain 6-1-2009 Spaniwood? English Language Spanish Films since the 1990s Cristina Sánchez-Conejero University of North Texas Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Sánchez-Conejero, Cristina (2009) "Spaniwood? English Language Spanish Films since the 1990s," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 33: Iss. 2, Article 8. https://doi.org/10.4148/ 2334-4415.1705 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spaniwood? English Language Spanish Films since the 1990s Abstract Is there such a thing as “Spanish identity”? If so, what are the characteristics that best define it? Since the early 1990s we have observed a movement toward young Spanish directors interested in making a different kind of cinema that departs markedly from the lighthearted landismo of the 70s and, later, the indulgent almodovarismo of the 80s. These new directors—as well as producers and actors—are interested in reaching out to wider audiences, in and outside of Spain. The internationalization they pursue comes, in many cases, with an adoption of the English language in their works. -

Cerramos El Programa De Abril

PROGRAMA CINE DORÉ Edición 2021 ONLINE ABRIL CINE ESPECTÁCULO AGNÈS VARDA RESTAURACIONES CINEMATECA PORTUGUESA FERNANDO FERNÁN GÓMEZ AMOS VOGEL (PUNTO DE VISTA) CRUZ DELGADO SOUND & VISION FILMOTECA: IVÁN “MELON” LEWIS JAZZ TRÍO / CALLE 54 ÍNDICE GENERAL Índice de películas .................................................................... 4 Introducción: “Otro paso más” .................................................... 6 Calendario Cine Doré ................................................................. 8 Calendario Flores en la sombra online ....................................... 18 Cine espectáculo .................................................................... 20 Agnès Varda. De mars à mai / De marzo a mayo �������������������������� 52 Restauraciones de la Cinemateca Portuguesa ............................ 74 Los 100 de Fernando Fernán Gómez .......................................... 88 Amos Vogel: Amos en el País de las Maravillas ........................... 98 Cruz Delgado. El quijote de la animación .................................. 106 Otras sesiones ..................................................................... 114 Filmoteca en familia .............................................................. 122 Mientras tanto: Cruz Delgado ................................................. 124 Cartel original de La venganza de Don Mendo Índice de películas ÍNDICE DE PELÍCULAS 2001: una odisea del espacio (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) .....................................24 La última cinta (Claudio Guerín Hill, 1969) ......................................................93