In the Mirror Game: Ubuntu Philosophy and Umbundu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portuguese Language in Angola: Luso-Creoles' Missing Link? John M

Portuguese language in Angola: luso-creoles' missing link? John M. Lipski {presented at annual meeting of the AATSP, San Diego, August 9, 1995} 0. Introduction Portuguese explorers first reached the Congo Basin in the late 15th century, beginning a linguistic and cultural presence that in some regions was to last for 500 years. In other areas of Africa, Portuguese-based creoles rapidly developed, while for several centuries pidginized Portuguese was a major lingua franca for the Atlantic slave trade, and has been implicated in the formation of many Afro- American creoles. The original Portuguese presence in southwestern Africa was confined to limited missionary activity, and to slave trading in coastal depots, but in the late 19th century, Portugal reentered the Congo-Angola region as a colonial power, committed to establishing permanent European settlements in Africa, and to Europeanizing the native African population. In the intervening centuries, Angola and the Portuguese Congo were the source of thousands of slaves sent to the Americas, whose language and culture profoundly influenced Latin American varieties of Portuguese and Spanish. Despite the key position of the Congo-Angola region for Ibero-American linguistic development, little is known of the continuing use of the Portuguese language by Africans in Congo-Angola during most of the five centuries in question. Only in recent years has some attention been directed to the Portuguese language spoken non-natively but extensively in Angola and Mozambique (Gonçalves 1983). In Angola, the urban second-language varieties of Portuguese, especially as spoken in the squatter communities of Luanda, have been referred to as Musseque Portuguese, a name derived from the KiMbundu term used to designate the shantytowns themselves. -

Guide to Missionary /World Christianity Bibles In

Guide to Missionary / World Christianity Bibles in the Yale Divinity Library Cataloged Collection The Divinity Library holds hundreds of Bibles and scripture portions that were translated and published by missionaries or prepared by church bodies throughout the world. Dating from the eighteenth century to the present day, these Bibles and scripture portions are currently divided between the historical Missionary Bible Collection held in Special Collections and the Library's regular cataloged collection. At this time it is necessary to search both the Guide to the Missionary / World Christianity Bible Collection and the online catalog to check on the availability of works in specific languages. Please note that this listing of Bibles cataloged in Orbis is not intended to be complete and comprehensive but rather seeks to provide a glimpse of available resources. Afroasiatic (Other) Bible. New Testament. Mbuko. 2010. o Title: Aban 'am wiya awan. Bible. New Testament. Hdi. 2013. o Title: Deftera lfida dzratawi = Le Nouveau Testament en langue hdi. Bible. New Testament. Merey. 2012. o Title: Dzam Wedeye : merey meq = Le Nouveau Testament en langue merey. Bible. N.T. Gidar. 1985. o Title: Halabara meleketeni. Bible. N.T. Mark. Kera. 1988. o Title: Kel pesan ge minti Markə jirini = L'évangile selon Marc en langue kera. Bible. N.T. Limba. o Title:Lahiri banama ka masala in bathulun wo, Yisos Kraist. Bible. New Testament. Muyang. 2013. o Title: Ma mu̳weni sulumani ge melefit = Le Nouveau Testament en langue Muyang. Bible. N.T. Mark. Muyang. 2005. o Title: Ma mʉweni sulumani ya Mark abəki ni. Bible. N.T. Southern Mofu. -

Hyman Paris Bantu PLAR

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report Title Disentangling Conjoint, Disjoint, Metatony, Tone Cases, Augments, Prosody, and Focus in Bantu Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/37p3m2gg Journal UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report, 9(9) ISSN 2768-5047 Author Hyman, Larry M Publication Date 2013 DOI 10.5070/P737p3m2gg eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UC Berkeley Phonology Lab Annual Report (2013) Disentangling Conjoint, Disjoint, Metatony, Tone Cases, Augments, Prosody, and Focus in Bantu Larry M. Hyman University of California, Berkeley Presented at the Workshop on Prosodic Constituents in Bantu languages: Metatony and Dislocations Université de Paris 3, June 28-29, 2012 1. Introduction The purpose of this paper is to disentangle a number of overlapping concepts that have been invoked in Bantu studies to characterize the relation between a verb and what follows it. Starting with the conjoint/disjoint distinction, I will then consider its potential relation to “metatony”, “tone cases”, “augments”, prosody, and focus in Bantu. 2. Conjoint/disjoint (CJ/DJ)1 In many Bantu languages TAM and negative paradigms have been shown to exhibit suppletive allomorphy, as in the following oft-cited Chibemba sentences, which illustrate a prefixal difference in marking present tense, corresponding with differences in focus (Sharman 1956: 30): (1) a. disjoint -la- : bus&é mu-la-peep-a ‘do you (pl.) smoke’? b. conjoint -Ø- : ee tu-peep-a sekelééti ‘yes, we smoke cigarettes’ c. disjoint -la- : bámó bá-la-ly-á ínsoka ‘some people actually eat snakes’ In (1a) the verb is final in its main clause and must therefore occur in the disjoint form, marked by the prefix -la-. -

A Discourse Analysis of Code-Switching Practices Among Angolan Migrants in Cape Town, South Africa

A Discourse Analysis of Code-Switching Practices among Angolan Migrants in Cape Town, South Africa Dinis Fernando da Costa (2865747) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Department of Linguistics, University of the Western Cape SUPERVISOR: PROF. Charlyn Dyers June 2010 i Abstract A Discourse Analysis of Code-Switching Practices among Angolan Migrants in Cape Town, South Africa Dinis Fernando da Costa This thesis is an extension of my BA (Honours) research essay, completed in 2008. This thesis is a more in-depth study of the issues involved in code switching among Angolan migrants living in Cape Town by increasing the scope of the research. The significance of this study lies in the fact that code-switching practices of Angolans in the Diaspora has not yet been investigated, and I hope that this potentially rich vein of research will be taken up by future studies. In this thesis, I explore the code-switching practices of long-term Angolans migrants in Cape Town when they interact with those who have been here for a much shorter period. In my Honours research essay, I revealed a tendency among those who have lived in Cape Town for some time to code-switch from Portuguese to English even in the presence of more recent migrants from Angola, who have little or no mastery of English. This thesis thus considers the effects of space, discourses of power, language ideologies and attitudes on the patterns of inter- and intra-sentential code-switching by these long-term migrants in interaction with each other as well as with the more recent “Angolan arrivals” in Cape Town. -

LANGUAGE Resolmce PROJECT David Dwyer and Kay Irish

Studies in African Linguistics Volume 13, Number 2, August 1982 LANGUAGE RESOlmCE PROJECT David Dwyer and Kay Irish Michigan State University The African Studies Center at Michigan State University has been awarded a grant from the U.S. Department of Education for the production of a handbook of human, institutional and material resources for the teaching and learning of African languages. Because of the existence of over 2000 languages now being spoken in Africa, this investigation has been restricted to the 82 highest pri ority languages established in a 4-tier ranking by the 1979 meeting of African ist linguists and area specialists representing the major African studies cen ters in the U.S. (See Wiley, David and David Dwyer, compilers, African Language Instruction in the United States: Directions and Priorities for the 19805, East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University, African Studies Center, 1980.) As a first step in this project we are assembling for each of the languages listed below a list of individuals throughout the world who are actively en gaged in scholarly studies in the language, whether teaching, linguistic re search, preparing language materials or producing literature. All scholars interested in being included or who have recommendations for inclusion should write to David Dwyer, Language Resource Project Director, or Kay Irish, Administrative Assistant, c/o African Studies Center, Room 100 In ternational Center, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, 48824. Please include the following: name and title (where relevant), correspondence address, language(s) appearing on the list for which the scholar has experience. Those responding will then be contacted for further information. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/25/2021 10:55:25PM Via Free Access Rainfall, Decreasing from the North to the South

AFRICA FOCUS, Vol.4, Nr.3-4, pp. 173-186. AFRICA REVIEW AN UP-TO-DATE GEOGRAPHICAL, HISTORICAL, POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC SUMMARY OF THE AFRICAN COUNTRIES* Prepared by F. Pauwels, P. Van Damme, D. Theeten, D. Beke, S. Hoste. ANGOLA 1. Official name: People's Republic of Angola Republica Popular de Angola 2. Geography: 2.1. Situation: Angola lies in the west-central part of southern Africa, between 6°S and l8°S, and ll 0 4S'E and 24°E. The district of Cabinda, north of the Zaire river, is part of Angola. 2.2. Total area: 1 246 700 km2 (incl. Cabinda: 7270 km2). 2.3. Natural regions: a 70-80 km large coastal zone separates the central highlands, ranging from 1000 to 2000 m alti tude, from the Atlantic Ocean. These plateaux are bordered by the Cristal Mountains in the north and the Chela Mountains in the south. Major river systems are the Kasai and the Zambezi-Okavango system, where altitu des well over 1000 m are found. Only the southern coastal zone is suited for cultivation. 2.4. Climate: tropical, with temperatures modified by the altitude and with a marked dry winter season throughout the country. The intertropical convergence zone brings f< Every issue of AFRIKA FOCUS will provide a survey of two or three African countries. The choice will be related, if possible, to articles in the issue. 173 Downloaded from Brill.com09/25/2021 10:55:25PM via free access rainfall, decreasing from the north to the south. The coastal zone has a lower rainfall, caused by the cooling effects of the Benguela current, restricting both convection and land temperatures, and thus lowering precipitation. -

Minorities and Indigenous Peoples Current Issues Background Contacts Resources

Angola - Minority Rights Group https://minorityrights.org/country/angola/ Minorities and indigenous peoples Current issues Background Contacts Resources Main languages: according to the 2014 Census, while the majority (71 per cent) of Angolans speak Portuguese – the only official language – at home, other languages spoken include Umbundu (23 per cent), Kikongo (8 per cent), Kimbundu (8 per cent), Chokwe (7 per cent), Nhaneca (3 per cent), Nganguela (3 per cent), Fiote (2 per cent), Kwanhama (2 per cent), Muhumbi (2 per cent), Luvale (1 per cent), others (4 per cent) Main religions: indigenous beliefs, Christianity Angola’s 2014 Census, the first since 1970, included information on language most used in the home, but not on ethnicity. Other sources indicate that Angola’s ethnic groups include Ovimbundu (37 per cent), Mbundu (25 per cent), Bakongo (13 per cent) and mestiço (2 per cent), Lunda-Chokwe (8 per cent), Nyaneka-Nkumbi (3 per cent), Ambo (2 per cent), Herero (up to 0.5 per cent), San 3,600 and Kwisi (up to 0.5 per cent). However, the international indigenous peoples’ rights organization IWGIA puts the number of indigenous people including San, Himba, Kwepe, Kuvale and Zwemba at around 25,000, amounting to 0.1 per cent of the total population, with San alone numbering between 5,000 and 14,000. The majority of today’s Angolans are Bantu peoples, including Ovimbundu, Mbundu and Bakongo, while the San belong to the indigenous Khoisan people. Traditionally a largely rural people of the central highlands, Ovimbundu migrated to the cities in large numbers in search of employment in the twentieth century. -

Dissertation.Pdf

Declaration I hereby declare that AN ANALYSIS OF VERBAL AFFIXES IN KIKONGO WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO FORM AND FUNCTION is to the best of my knowledge and belief, original and my own work. The material has not been submitted, either in whole or part, for a degree at this or any other institution of learning. The contents of this study are the product of my intellect, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text or somewhere else. The strengths and weaknesses of this work are wholly my own. ………………………………….. Mbiavanga Fernando Abstract The relation between verbal affixes and their effect on the predicate argument structure of the verbs that host them has been the focus of many studies in linguistics, with special reference to Bantu languages in recent years. Given the colonial policy on indigenous languages in Angola, Kikongo, as is the case of other Bantu languages in that country, has not been sufficiently studied. This study explores the form and function of six verbal affixes, including the order in which they occur in the verb stem. The study maintains that the applicative and causative are valency-increasing verbal affixes and, as such, give rise to double object constructions in Kikongo. The passive, reciprocal, reflexive and stative are valency-decreasing and, as such, they reduce the valency of the verb by one object. This study also suggests that Kikongo is a symmetrical object language in which both objects appear to have equal status. ii Ded ication In memory of my father, and for my mother who always believes that ‘mungwa kani kunsuka zenzila’ better late than never iii Acknowledgements ‘If the LORD does not build the house, the work of the builders is useless; if the LORD does not protect the city, it does no good for the sentries to stand guard. -

Morphological and Phonological Prefixation: a Case from Zulu

Word-level and phrase-level prefixes in Zulu * Jochen Zeller, University of Natal, Durban 1. Introduction In Zulu, one of the nine officially recognised Bantu languages of South Africa, the predicate of a relative clause is usually modified with a prefix which expresses both relativisation and agreement with the subject of the relative clause (a so-called relative concord). However, there is a second strategy of relative clause formation in Zulu in which the relative concord seems to be prefixed to the initial noun of the relative clause. In this position, it no longer agrees with the relative clause subject, but with the head noun of the construction. This paper investigates these two different relative clause formation strategies in Zulu. In sections 2 and 3, the properties of the two strategies are outlined and discussed. I assume that the relative concord in the first strategy is a word- level prefix which morphologically combines with the predicative stem of the relative clause. I then argue in section 4 that the relative concord in the second strategy is prefixed to the relative clause as a whole. Following a proposal articulated in Anderson (1992), I analyse this kind of "phrasal affixation" in terms of cliticisation. I assume that the relative marker in these constructions is a clitic which uses the initial noun of the relative clause as its phonological host. In section 5 I suggest that the relativising phrasal affix of the second strategy represents an intermediate stage of a grammaticalisation process that derived the relative concord of the first strategy from an earlier relative clause construction in Zulu which used relative pronouns. -

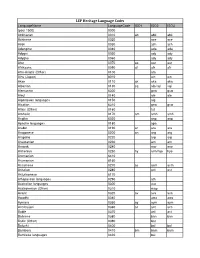

LEP Heritage Language Codes

LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 (post 1500) 0000 Abkhazian 0010 ab abk abk Achinese 0020 ace ace Acoli 0030 ach ach Adangme 0040 ada ada Adygei 0050 ady ady Adyghe 0060 ady ady Afar 0070 aa aar aar Afrikaans 0090 af afr afr Afro-Asiatic (Other) 0100 afa Ainu (Japan) 6010 ain ain Akan 0110 ak aka aka Albanian 0130 sq alb/sqi sqi Alemannic 6300 gsw gsw Aleut 0140 ale ale Algonquian languages 0150 alg Alsatian 6310 gsw gsw Altaic (Other) 0160 tut Amharic 0170 am amh amh Angika 6020 anp anp Apache languages 0180 apa Arabic 0190 ar ara ara Aragonese 0200 an arg arg Arapaho 0220 arp arp Araucanian 0230 arn arn Arawak 0240 arw arw Armenian 0250 hy arm/hye hye Aromanian 6410 Arumanian 6160 Assamese 0270 as asm asm Asturian 0280 ast ast Asturleonese 6170 Athapascan languages 0290 ath Australian languages 0300 aus Austronesian (Other) 0310 map Avaric 0320 av ava ava Awadhi 0340 awa awa Aymara 0350 ay aym aym Azerbaijani 0360 az aze aze Bable 0370 ast ast Balinese 0380 ban ban Baltic (Other) 0390 bat Baluchi 0400 bal bal Bambara 0410 bm bam bam Bamileke languages 0420 bai LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 Banda 0430 bad Bantu (Other) 0440 bnt Basa 0450 bas bas Bashkir 0460 ba bak bak Basque 0470 eu baq/eus eus Batak (Indonesia) 0480 btk Bedawiyet 6180 bej bej Beja 0490 bej bej Belarusian 0500 be bel bel Bemba 0510 bem bem Bengali; ben 0520 bn ben ben Berber (Other) 0530 ber Bhojpuri 0540 bho bho Bihari 0550 bh bih Bikol 0560 bik bik Bilin 0570 byn byn Bini 0580 bin bin Bislama -

Angola – Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 11 March 2011

Angola – Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 11 March 2011. Information on whether the following languages Lingala and Bakongo/Kicongo are spoken in Angola. A report by the Home Office UK Border Agency under the heading ‘Geography’ states: “Angola is located in southern Africa, bordering the South Atlantic Ocean, between Namibia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It also has borders with the Republic of the Congo, Namibia and Zambia. The overall land area of the country is 1,246,700 sq km. The ethnic groups that make up the Angolan population are the Ovimbundu (37%), Kimbundu (25%), Bakongo (13%), mestico (mixed European and native African) (2%), European (1%), and other ethnic groups (22%)…”(United Kingdom Border Agency (1 September 2010) Country of Origin Information Report – Angola pg. 6 par. 1.02) It also states: “According to Travlang.com (accessed on 16 June 2010), the official language of Angola is Portuguese. Other languages spoken include Umbundu, Kimbundu, Kongo, Chokwe, Lwena and Lunda. As regards the languages spoken by the people of Cabinda, Ethnologue (accessed on 22 July 2010) lists Koongo (aka Kongo, Kikongo, Kikoongo, Congo, Cabinda) and Yombe (aka Kiyombe, Kiombi, Lombe and Bayombe) as the languages spoken in that province. According to a Global Security report about Cabinda, “Cabindês is the National Language of Cabinda. However, a large number of Cabinda Citizens speak French. The Cabindans at least, for the literate among them, are 90% French speaking and only 10% speak Portuguese.” (ibid) A report by the United States Department of State states: “Ethnic groups: Ovimbundu 37%, Kimbundu 25%, Bakongo 13%, mixed racial 2%, European 1%. -

Revising the Bantu Tree

Cladistics Cladistics (2018) 1–20 10.1111/cla.12353 Revising the Bantu tree Peter M. Whiteleya, Ming Xuea and Ward C. Wheelerb,* aDivision of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History, 200 Central Park West, New York, NY, 10024-5192, USA; bDivision of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, 200 Central Park West, New York, NY, 10024-5192, USA Accepted 15 June 2018 Abstract Phylogenetic methods offer a promising advance for the historical study of language and cultural relationships. Applications to date, however, have been hampered by traditional approaches dependent on unfalsifiable authority statements: in this regard, historical linguistics remains in a similar position to evolutionary biology prior to the cladistic revolution. Influential phyloge- netic studies of Bantu languages over the last two decades, which provide the foundation for multiple analyses of Bantu socio- cultural histories, are a major case in point. Comparative analyses of basic lexica, instead of directly treating written words, use only numerical symbols that express non-replicable authority opinion about underlying relationships. Building on a previous study of Uto-Aztecan, here we analyse Bantu language relationships with methods deriving from DNA sequence optimization algorithms, treating basic vocabulary as sequences of sounds. This yields finer-grained results that indicate major revisions to the Bantu tree, and enables more robust inferences about the history of Bantu language expansion and/or migration throughout sub-Saharan Africa. “Early-split” versus “late-split” hypotheses for East and West Bantu are tested, and overall results are com- pared to trees based on numerical reductions of vocabulary data. Reconstruction of language histories is more empirically based and robust than with previous methods.