Rabbi Eleazar's Peru Ah* T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Arba 'Ah Turim of Rabbi Jacob Ben Asher on Medical Ethics, ” Rabbi David Fink, Ph.D

Arba`ah Turim of Rabbi Jacob ben Asher on Medical Ethics Rabbi David Fink, Ph.D. Rabbi Jacob ben Asher was a leading halachic authority of the early part of the fourteenth century. As a young man he accompanied his father, Rabbi Asher ben Yechiel (Rosh), from Germany to Spain. In Toledo he wrote a number of basic halachic and exegetical works. The most important of these are the Arba`ah Turim, which later became the basis of Rabbi Joseph Karo’s Shulchan Aruch. The following passage is taken from section 336 of the second book (Yoreh De`ah) of the Arba`ah Turim. It deals with the obligations of medical practitioners. Rabbi Jacob’s opinions on this topic became the subject of commentary and analysis by the leading halachic scholars of subsequent generations. At the School of Rabbi Ishmael it was taught that the verse “And he shall heal (Ex. 21:19)” implies that the physician is permitted to heal.1 One should not disregard pain for fear of making a mistake and inadvertently killing the patient. Rather one must be exceedingly cautious as is proper in any capital case. Further, one should not say that if God has smitten the patient, it is improper to heal him, it being unnatural for mortals to restore health, even though they are accustomed to do so.2 Thus it says, “Yet in his disease he sought not to the Lord, but to the physicians (2 Chr. 16:12)”. From this we learn that the physician is permitted to heal and that healing is a part of the commandment of lifesaving. -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. -

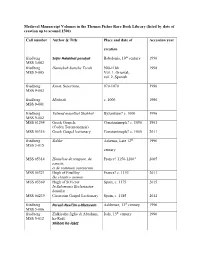

Medieval Manuscript Volumes in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (Listed by Date of Creation up to Around 1500) Call Number Au

Medieval Manuscript Volumes in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (listed by date of creation up to around 1500) Call number Author & Title Place and date of Accession year creation friedberg Sefer Halakhot pesuḳot Babylonia, 10 th century 1996 MSS 3-002 friedberg Ḥamishah ḥumshe Torah 900-1188 1998 MSS 9-005 Vol. 1, Oriental; vol. 2, Spanish. friedberg Kinot . Selections. 970-1070 1996 MSS 9-003 friedberg Mishnah c. 1000 1996 MSS 9-001 friedberg Talmud masekhet Shabbat Byzantium? c. 1000 1996 MSS 9-002 MSS 01244 Greek Gospels Constantinople? c. 1050 1901 (Codex Torontonensis) MSS 05316 Greek Gospel lectionary Constantinople? c. 1050 2011 friedberg Siddur Askenaz, Late 12 th 1996 MSS 3-015 century MSS 05314 Homeliae de tempore, de France? 1150-1200? 2005 sanctis, et de communi sanctorum MSS 05321 Hugh of Fouilloy. France? c. 1153 2011 De claustro animae MSS 03369 Hugh of StVictor Spain, c. 1175 2015 In Salomonis Ecclesiasten homiliæ MSS 04239 Cistercian Gospel Lectionary Spain, c. 1185 2012 friedberg Perush Neviʼim u-Khetuvim Ashkenaz, 13 th century 1996 MSS 5-006 friedberg Zidkiyahu figlio di Abraham, Italy, 13 th century 1996 MSS 5-012 ha-Rofè. Shibole ha-leḳeṭ friedberg David Kimhi. Spain or N. Africa, 13th 1996 MSS 5-010 Sefer ha-Shorashim century friedberg Ketuvim Spain, 13th century 1996 MSS 5-004 friedberg Beʼur ḳadmon le-Sefer ha- 13th century 1996 MSS 3-017 Riḳmah MSS 04404 William de Wycumbe. Llantony Secunda?, c. 1966 Vita venerabilis Roberti Herefordensis 1200 MSS 04008 Liber quatuor evangelistarum Avignon? c. 1220 1901 MSS 04240 Biblia Latina England, c. -

Title Listing of Sixteenth Century Books

Title Listing of Sixteenth Century Books Abudarham, David ben Joseph Abudarham, Fez, De accentibus et orthographia linguae hebraicae, Johannes Reuchlin, Hagenau, Adam Sikhli, Simeon ben Samuel, Thiengen, Adderet Eliyahu, Elijah ben Moses Bashyazi, Constantinople, Ha-Aguddah, Alexander Suslin ha-Kohen of Frankfurt, Cracow, Agur, Jacob Barukh ben Judah Landau, Rimini, Akedat Yitzhak, Isaac ben Moses Arama, Salonika, Aleh Toledot Adam . Kohelet Ya’akov, Baruch ben Moses ibn Baruch, Venice, – Alfasi (Sefer Rav Alfas), Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi (Rif), Constantinople, Alfasi (Hilkhot Rav Alfas), Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi (Rif), Sabbioneta, – Alfasi (Sefer Rav Alfas), Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi (Rif), Riva di Trento, Alphabetum Hebraicum, Aldus Manutius, Venice, c. Amadis de Gaula, Constantinople, c. Amudei Golah (Semak), Isaac ben Joseph of Corbeil, Constantinople, c. Amudei Golah (Semak), Isaac ben Joseph of Corbeil, Cremona, Arba’ah ve’Esrim (Bible), Pesaro, – Arba’ah Turim, Jacob ben Asher, Fano, Arba’ah Turim, Jacob ben Asher, Augsburg, Arba’ah Turim, Jacob ben Asher, Constantinople, De arcanis catholicae veritatis, Pietro Columna Galatinus, Ortona, Arukh, Nathan ben Jehiel, Pesaro, Asarah Ma’amarot, Menahem Azariah da Fano, Venice, Avkat Rokhel, Machir ben Isaac Sar Hasid, Augsburg, Avkat Rokhel, Machir ben Isaac Sar Hasid—Venice, – Avodat ha-Levi, Solomon ben Eliezer ha-Levi, Venice, Ayumah ka-Nidgaloth, Isaac ben Samuel Onkeneira, Constantinople, Ayyalah Sheluhah, Naphtali Hirsch ben Asher Altschuler, Cracow, c. Ayyelet -

1 the Image of Jacob Engraved Upon the Throne: Further Reflection on the Esoteric Doctrine of the German Pietists

1 The Image of Jacob Engraved upon the Throne: Further Reflection on the Esoteric Doctrine of the German Pietists Verily, at this time that which was hidden has been revealed because forgetfulness has reached its final limit; the end of forgetfulness is the beginning of remembrance. Abraham Abulafia,'Or ha-Sekhel, MS Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek 92, fol. 59b I One of the most interesting motifs in the world of classical rabbinic aggadah is that of the image of Jacob engraved on the throne of glory. My intention in this chapter is to examine in detail the utilization of this motif in the rich and varied literature of Eleazar ben Judah of Worms, the leading literary exponent of the esoteric and mystical pietism cultivated by the Kalonymide circle of German Pietists in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The first part of the chapter will investigate the ancient traditions connected to this motif as they appear in sources from Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages in order to establish the basis for the distinctive understanding that evolves in the main circle of German Pietists to be discussed in the second part. As I will argue in detail later, the motif of the image of Jacob has a special significance in the theosophy of the German Pietists, particularly as it is expounded in the case of Eleazar. The amount of attention paid by previous scholarship to this theme is disproportionate in relation to the central place that it occupies in the esoteric ruminations of the Kalonymide Pietists. 1 From several passages in the writings of Eleazar it is clear that the motif of the image of Jacob is covered and cloaked in utter secrecy. -

Appendix: a Guide to the Main Rabbinic Sources

Appendix: A Guide to the Main Rabbinic Sources Although, in an historical sense, the Hebrew scriptures are the foundation of Judaism, we have to turn elsewhere for the documents that have defined Judaism as a living religion in the two millennia since Bible times. One of the main creative periods of post-biblical Judaism was that of the rabbis, or sages (hakhamim), of the six centuries preceding the closure of the Babylonian Talmud in about 600 CE. These rabbis (tannaim in the period of the Mishnah, followed by amoraim and then seboraim), laid the foundations of subsequent mainstream ('rabbinic') Judaism, and later in the first millennium that followers became known as 'rabbanites', to distinguish them from the Karaites, who rejected their tradition of inter pretation in favour of a more 'literal' reading of the Bible. In the notes that follow I offer the English reader some guidance to the extensive literature of the rabbis, noting also some of the modern critical editions of the Hebrew (and Aramaic) texts. Following that, I indicate the main sources (few available in English) in which rabbinic thought was and is being developed. This should at least enable readers to get their bearings in relation to the rabbinic literature discussed and cited in this book. Talmud For general introductions to this literature see Gedaliah Allon, The Jews in their Land in the Talmudic Age, 2 vols (Jerusalem, 1980-4), and E. E. Urbach, The Sages, tr. I. Abrahams (Cambridge, Mass., and London: Harvard University Press, 1987), as well as the Reference Guide to Adin Steinsaltz's edition of the Babylonian Talmud (see below, under 'English Transla tions'). -

Sixteenth-Century Hebrew Books in the Library of Congress

Sixteenth-Century Hebrew Books at the Library of Congress A Finding Aid פה Washington D.C. June 18, 2012 ` Title-page from Maimonides’ Moreh Nevukhim (Sabbioneta: Cornelius Adelkind, 1553). From the collections of the Hebraic Section, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. i Table of Contents: Introduction to the Finding Aid: An Overview of the Collection . iii The Collection as a Testament to History . .v The Finding Aid to the Collection . .viii Table: Titles printed by Daniel Bomberg in the Library of Congress: A Concordance with Avraham M. Habermann’s List . ix The Finding Aid General Titles . .1 Sixteenth-Century Bibles . 42 Sixteenth-Century Talmudim . 47 ii Sixteenth-Century Hebrew Books in the Library of Congress: Introduction to the Finding Aid An Overview of the Collection The art of Hebrew printing began in the fifteenth century, but it was the sixteenth century that saw its true flowering. As pioneers, the first Hebrew printers laid the groundwork for all the achievements to come, setting standards of typography and textual authenticity that still inspire admiration and awe.1 But it was in the sixteenth century that the Hebrew book truly came of age, spreading to new centers of culture, developing features that are the hallmark of printed books to this day, and witnessing the growth of a viable book trade. And it was in the sixteenth century that many classics of the Jewish tradition were either printed for the first time or received the form by which they are known today.2 The Library of Congress holds 675 volumes printed either partly or entirely in Hebrew during the sixteenth century. -

The Reception of Rashi's Commentary On

T HE J EWISH Q UARTERLY R EVIEW, Vol. 97, No. 1 (Winter 2007) 33–66 The Reception of Rashi’s Commentary on the Torah inSpain:TheCaseofAdam’s Mating with the Animals ERIC LAWEE WHILE R ASHI’S BIBLICAL COMMENTARY has profited from extensive and more or less uninterrupted scholarly inquiry,1 considerably less atten- tion has been devoted to the varied reactions over the ages to his scrip- tural exegesis.2 The sorts of questions rightly posed with respect to Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah should also be asked about Rashi’s Commen- tary on the Torah: ‘‘Where and when did the book penetrate first? Who were its sponsors and opponents? What were the initial steps, or stages, in its adoption everywhere?’’3 This essay seeks to illumine an aspect of the Research for this article was made possible by a UCLA Center for Jewish Studies Maurice Amado Foundation Research Grant in Sephardic Studies and by grants from the Faculty of Arts of York University, Toronto. It was written while I enjoyed a Visiting Fellowship from the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. Ephraim Kanarfogel, Martin Lockshin, and B. Barry Levy helpfully commented on a draft, while JQR’s anonymous readers significantly improved a later version. I wish to express my thanks to these individuals and institutions for their aid. 1. For bibliographic orientation, see Avraham Grossman, ‘‘The School of Lit- eral Jewish Exegesis in Northern France,’’ Hebrew Bible / Old Testament, vol. 1, pt. 2, From the Beginnings to the Middle Ages: The Middle Ages, ed. M. Sæbø (Go¨ttingen, 2000), 321–22. -

Concise and Succinct: Sixteenth Century Editions of Medieval Halakhic Compendiums*

109 Concise and Succinct: Sixteenth Century Editions of Medieval Halakhic Compendiums* By: MARVIN J. HELLER* “Then Joseph commanded to fill their sacks with grain, and to restore every man’s money into his sack, and to give them provision for the way (zeidah la-derekh); and thus did he to them.” (Genesis 42:25) “And the people of Israel did so; and Joseph gave them wagons, accord- ing to the commandment of Pharaoh, and gave them provision for the way (zeidah la-derekh).” (Genesis 45:21) “And our elders and all the inhabitants of our country spoke to us, saying, Take provisions (zeidah la-derekh) with you for the journey, and go to meet them, and say to them, We are your servants; therefore now make a covenant with us.” (Joshua 9:11) We are accustomed to thinking of concise, succinct, popular halakhic digests, such as R. Abraham Danzig’s (Danziger, 1748– 1820) Hayyei Adam on Orah Hayyim with an addendum entitled Nishmat Adam (Vilna, 1810) and Hokhmat Adam with an addendum called Binat Adam (1814-15) and R. Solomon ben Joseph Ganzfried’s (1801–66) Kizur Shulhan Arukh (Uzhgorod, 1864) as a * I would like to express my appreciation to Eli Genauer for reading this article and for his suggestions. ________________________________________________________ Marvin J. Heller writes books and articles on Hebrew printing and bibliography. His Printing the Talmud: A History of the Individual Treatises Printed from 1700 to 1750 (Brill, Leiden, 1999), and The Six- teenth Century Hebrew Book: An Abridged Thesaurus (Brill, Leiden, 2004) were, respectively, recipients of the 1999 and 2004 Research and Special Libraries Division Award of the Association of Jewish Libraries for Bibliography. -

A Catalogue of the Blau Collection of Hebrew Books in the University of Glasgow Library

A Catalogue of the Blau Collection of Hebrew books in the University of Glasgow Library Lajos or Ludwig Blau was a Hungarian scholar and rabbi, born April 29, 1861, at Putnok, Hungary, and educated at three different yeshivas, among them that of Presburg, and at the Landesrabbinerschule (Rabbinical Seminary) in Budapest (1880-88). He studied philosophy and Orientalia at the University of Budapest, receiving his doctorate there, cum laude, in 1887, and the rabbinical diploma in 1888. While still a student in 1887, Blau was invited to be a teacher of the Talmud at the Seminary subsequently becoming, in 1889, professor of the Bible, the Hebrew and Aramaic languages, and Talmud. Also in 1899, he became librarian and tutor in Jewish history. In 1914 Blau was appointed director of the Seminary. For 40 years from 1891 until 1931 he was the editor of the Jewish journal, Magyar Zsidó Szemle (Hungarian Jewish Review), initially with Ferenc Mezey, who conducted a publicity campaign for the recognition of Judaism as a received, or state supported religion. Mezey left the journal in 1896 when this aim was achieved, and under the sole editorship of Blau the periodical became purely scholarly. The journal was recognised as an official organ of the Rabbinical Seminary from 1927 onwards. The Hungarian language of the review tended to isolate Hungarian Jewish studies, and obscure the full importance of Blau’s scholarly output. In 1911 he founded the Hebrew journal ha-Ṣofeh me-Ereṣ Hagar (later ha-Ṣofeh le-Ḥokhmat Yisrael) which he edited until 1931. Blau was a prolific scholar who contributed to many aspects of Jewish learning, contributing to most of the Jewish and non-Jewish scholarly journals devoted to theology and philology. -

Hans-Georg Von Mutius Taking Interest from Non-Jews – Main Problems in Traditional Jewish Law

Hans-Georg von Mutius Taking Interest from Non-Jews – Main Problems in Traditional Jewish Law Questions of money lending between Jews and non-Jews and the problems of in- terest-charged loans can be viewed through the mirror of Jewish law and have been discussed by rabbinical authorities. To begin with the legal sources: All Jewish communities of the Middle Ages in the Mediterranean area and in non-Mediterra- nean Europe have a common stock of Holy Scriptures constituting the basis of their legal culture and life. Apart from the Hebrew Bible with the Pentateuch as the main law book, they all have in common use a corpus of legal und ritual works written in Palestine and Babylonia during the Late Antiquities: the Mishna com- piled at the beginning of the 3rd century C.E. in Northern Palestine, constituting the first comprehensive law-book of normative Judaism after the destruction of the Second Temple with laws and legal discussions mainly from the 2nd century; then a commentary to the Mishna in form of the Babylonian Talmud containing laws and legal discussions from the 3rd to the 6th century; further legal corpora of secondary importance as the Tosefta and the Palestinian Talmud from the 4th and 5th centuries; and the bulk of the so-called Midrashic literature. Midrashic litera- ture, of Jewish Palestinian origin, presents the rabbinical expositions of scriptural verses. Embodied into this literature is a canonical corpus of Midrashim with laws and legal discussions from the 2nd to the 3rd centuries expounding the laws of the Pentateuch. These legal or Halakhic Midrashim were, in addition to the Mishna and the Babylonian Talmud, of obligatory significance for every community in the medieval Jewish world. -

The Justification for Controversy Under Jewish Law

The Justification for Controversy Under Jewish Law Jeffrey I. Roth TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ................................................... 338 I. A Case Study in Controversy and Dissent: Release from Combat Duty ............................................. 340 II. Explanations for Controversy that Undermine the Value of D issent ................................................... 351 A. The Minimizing Approach ........................... 352 B. Faults in the Chain of Transmission ................... 355 1. Blaming Weak Links in the Chain for Inadvertent Errors ............................................ 355 2. Shortcomings of the Weak Link Theory ........... 358 C. Controversy as a Historical Phenomenon .............. 362 D. Controversy as Inevitable but Regrettable ............. 367 III. The Justification for Controversy in Jewish Law: Controversy as Inherent and Desirable .................... 370 A. The Choice Among Options .......................... 372 B. The Continuing Revelation ........................... 373 C. The Complex Reality ................................. 374 D. Hallmarks of a Satisfactory Explanation for Halakhic Controversy .......................................... 376 IV. The Functions of Dissent in Jewish Law ................... 377 A. Issue-Sharpening ..................................... 378 B. Meeting the Needs of Hard Cases ..................... 379 C. Responding to the Challenge of Hard Times ........... 380 D. Providing Partial Self-Justification for Noncomforming Conduct ............................................