Hans-Georg Von Mutius Taking Interest from Non-Jews – Main Problems in Traditional Jewish Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TALMUDIC STUDIES Ephraim Kanarfogel

chapter 22 TALMUDIC STUDIES ephraim kanarfogel TRANSITIONS FROM THE EAST, AND THE NASCENT CENTERS IN NORTH AFRICA, SPAIN, AND ITALY The history and development of the study of the Oral Law following the completion of the Babylonian Talmud remain shrouded in mystery. Although significant Geonim from Babylonia and Palestine during the eighth and ninth centuries have been identified, the extent to which their writings reached Europe, and the channels through which they passed, remain somewhat unclear. A fragile consensus suggests that, at least initi- ally, rabbinic teachings and rulings from Eretz Israel traveled most directly to centers in Italy and later to Germany (Ashkenaz), while those of Babylonia emerged predominantly in the western Sephardic milieu of Spain and North Africa.1 To be sure, leading Sephardic talmudists prior to, and even during, the eleventh century were not yet to be found primarily within Europe. Hai ben Sherira Gaon (d. 1038), who penned an array of talmudic commen- taries in addition to his protean output of responsa and halakhic mono- graphs, was the last of the Geonim who flourished in Baghdad.2 The family 1 See Avraham Grossman, “Zik˙atah shel Yahadut Ashkenaz ‘el Erets Yisra’el,” Shalem 3 (1981), 57–92; Grossman, “When Did the Hegemony of Eretz Yisra’el Cease in Italy?” in E. Fleischer, M. A. Friedman, and Joel Kraemer, eds., Mas’at Mosheh: Studies in Jewish and Moslem Culture Presented to Moshe Gil [Hebrew] (Jerusalem, 1998), 143–57; Israel Ta- Shma’s review essays in K˙ ryat Sefer 56 (1981), 344–52, and Zion 61 (1996), 231–7; Ta-Shma, Kneset Mehkarim, vol. -

277 53 Anna D. Kartsonis, Anastasis

Book reviews 277 53 Anna D. Kartsonis, Anastasis: The Making of an Image (Princeton, Princeton Univ. Press), 1986, pp. 263 & 89 illustrations, 21 x 28 cm., $51.50, ISBN 0-691-04039-7. LEXIKON DES MITTELALTERS - II: JUDAISM. Lexikon des Mittelalters. Erster Band, 2110 col. (Oct.1977-Nov.1980): Aachen- Bettelordenskirchen. Zweiter Band, 2210 col. (May 1981-November 1983): Bettlerwesen-Codex von Valencia. Dritter Band, 2208 col. (May 1984-June 1986): Codex Wintoniensis- Erziehungs- und Bildungswesen). Vierter Band, Lief. 1-7 (1567 col.): Erzkanzler-Goslar (March 1987- - December 1988) München und Zürich, Artemis Verlag. The Lexikon des Mittelalters (hereafter: LM) aims at covering all aspects of the history of the European Middle Ages, viz. the period between A.D. 300 and 1500. It has already been illustrated in a previous review that LM, though primarily a reference-work for students of European medieval history, can be of great use to islamicists as well, in view of the high standard of the articles related, in one way or another, to Islam (Numen vol XXX, pp. 265-268). The present review aims at presenting an evaluation of the contributions of LM in the field of Jewish studies. At this point it should be stressed that the editorial preface of November 1980 stated:, "Ebenso ist die Geschichte des mittelalterlichen europaischen Judentums fester Bestandteil des Lexikons" (my italics, VK). In the volumes covering the letters A through G I have counted a total number of some 90 articles on Jewish subjects. This number has to be considered as an approximate one only, as I most likely have overlooked several items going through the enormous mass of articles published thus far. -

Why Was Maimonides Controversial?

12 Nov 2014, 19 Cheshvan 5775 B”H Congregation Adat Reyim Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Adult Education Why was Maimonides controversial? Introduction Always glad to talk about Maimonides: He was Sephardic (of Spanish origin), and so am I He lived and worked in Egypt, and that's where I was born and grew up His Hebrew name was Moshe (Moses), and so is mine He was a rationalist, and so am I He was a scientist of sorts, and so am I He had very strong opinions, and so do I And, oh yes: He was Jewish, and so am I. -Unfortunately, he probably wasn’t my ancestor. -Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, aka Maimonides, aka The Rambam: b. 1135 (Córdoba, Muslim Spain) – d. 1204 (Fostat, Egypt): Torah scholar, philosopher, physician: Maimonides was the most illustrious figure in Judaism in the post-talmudic era, and one of the greatest of all time… His influence on the future development of Judaism is incalculable. No spiritual leader of the Jewish people in the post- talmudic period has exercised such an influence both in his own and subsequent generations. [Encyclopedia Judaica] -Best-known for Mishneh Torah and Guide for the Perplexed: -Mishneh Torah (Sefer Yad ha-Chazaka) codifies Jewish law. Gathers all laws from Talmud and adds rulings of later Sages. Clear, concise, and logical. No personal opinions. -The Guide for the Perplexed (Dalalat al-Ha'erin; Moreh Nevukhim) is a non-legal philosophical work, for general public, that bridges Jewish and Greek thought. -Controversial in his lifetime and for many centuries afterwards. Controversies concerning Maimonides 1-No need to study Talmud -He appears to downplay study of Talmud. -

Wirtschaftsgeschichte Der Mittelalterlichen Juden Fragen Und Einschätzungen

Wirtschaftsgeschichte der mittelalterlichen Juden Fragen und Einschätzungen Herausgegeben von Michael Toch unter Mitarbeit von Elisabeth Müller- Luckner R. Oldenbourg Verlag München 2008 JcoS/ J_A+CJ Hans-Georg von Mutius Taking Interest from Non-Jews - Main Problems in Traditional Jewish Law Questions of money lending between Jews and non-Jews and the problems of in- terest-charged loans can be viewed through the mirror of Jewish law and have been discussed by rabbinical authorities. To begin with the legal sources: All Jewish communities of the Middle Ages in the Mediterranean area and in non-Mediterra- nean Europe have a common stock of Holy Scriptures constituting the basis of their legal culture and life. Apart from the Hebrew Bible with the Pentateuch as the main law book, they all have in common use a corpus of legal und ritual works written in Palestine and Babylonia during the Late Antiquities: the Mishna com- piled at the beginning of the 3rd century C.E. in Northern Palestine, constituting the first comprehensive law-book of normative Judaism after the destruction of the Second Temple with laws and legal discussions mainly from the 2nd century; then a commentary to the Mishna in form of the Babylonian Talmud containing laws and legal discussions from the Jrd to the 6th century; further legal corpora of secondary importance as the Tosefta and the Palestinian Talmud from the 4th and 5th centuries; and the bulk of the so-called Midrashic literature. Midrashic litera- ture, of Jewish Palestinian origin, presents the rabbinical expositions of scriptural verses. Embodied into this literature is a canonical corpus of Midrashim with laws and legal discussions from the 2nd to the yd centuries expounding the laws of the Pentateuch. -

“Arba 'Ah Turim of Rabbi Jacob Ben Asher on Medical Ethics, ” Rabbi David Fink, Ph.D

Arba`ah Turim of Rabbi Jacob ben Asher on Medical Ethics Rabbi David Fink, Ph.D. Rabbi Jacob ben Asher was a leading halachic authority of the early part of the fourteenth century. As a young man he accompanied his father, Rabbi Asher ben Yechiel (Rosh), from Germany to Spain. In Toledo he wrote a number of basic halachic and exegetical works. The most important of these are the Arba`ah Turim, which later became the basis of Rabbi Joseph Karo’s Shulchan Aruch. The following passage is taken from section 336 of the second book (Yoreh De`ah) of the Arba`ah Turim. It deals with the obligations of medical practitioners. Rabbi Jacob’s opinions on this topic became the subject of commentary and analysis by the leading halachic scholars of subsequent generations. At the School of Rabbi Ishmael it was taught that the verse “And he shall heal (Ex. 21:19)” implies that the physician is permitted to heal.1 One should not disregard pain for fear of making a mistake and inadvertently killing the patient. Rather one must be exceedingly cautious as is proper in any capital case. Further, one should not say that if God has smitten the patient, it is improper to heal him, it being unnatural for mortals to restore health, even though they are accustomed to do so.2 Thus it says, “Yet in his disease he sought not to the Lord, but to the physicians (2 Chr. 16:12)”. From this we learn that the physician is permitted to heal and that healing is a part of the commandment of lifesaving. -

The Early Ibn Ezra Supercommentaries: a Chapter in Medieval Jewish Intellectual History

Tamás Visi The Early Ibn Ezra Supercommentaries: A Chapter in Medieval Jewish Intellectual History Ph.D. dissertation in Medieval Studies Central European University Budapest April 2006 To the memory of my father 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction............................................................................................................................... 7 Prolegomena............................................................................................................................ 12 1. Ibn Ezra: The Man and the Exegete ......................................................................................... 12 Poetry, Grammar, Astrology and Biblical Exegesis .................................................................................... 12 Two Forms of Rationalism.......................................................................................................................... 13 On the Textual History of Ibn Ezra’s Commentaries .................................................................................. 14 Ibn Ezra’s Statement on Method ................................................................................................................. 15 The Episteme of Biblical Exegesis .............................................................................................................. 17 Ibn Ezra’s Secrets ....................................................................................................................................... -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. -

Introduction to JUDAISM WEEK 3 GOD IS ONE JEWISH VIEWS of GOD Adonai Echad

Temple Sinai, S. Burlington, VT. Rabbi David Edleson Introduction to JUDAISM WEEK 3 GOD IS ONE JEWISH VIEWS OF GOD Adonai Echad Do you have to believe in God to be Jewish? Jews and God by the Numbers Pew 2013 Jews and God by the Numbers Pew 2018 . Shabbat Stalwarts – regular participation in prayer and other religious practices 21% . God and Country Believers- express their religion through political and social conservatism 8% . Diversely Devout- follow the Bible but also believe in things like animism and reincarnation. 5% . Relaxed Religious- believe in God and pray but don’t engage in many traditional practices 14% . Spiritually Awake – hold some New Age beliefs 8% . Religious Resisters – believe in a higher power but have negative views of organized religion 17% . Solidly Secular- don’t believe in God and do not self-define as religious 28% Jews and God by the Numbers Pew 2018 45 percent of American Jews are listed in the two categories for the least religious: “religion resisters,” who believe in a higher power but have negative views of organized religion, or “solidly secular,” those who don’t believe in God and do not self-define as religious. The breakdown is 28 percent as “solidly secular” and 17 percent as “religion resisters.” “Jewish Americans are the only religious group with substantial contingents at each end of the typology,” the study says. Maimonides’13 Articles of Faith Principle 1 I believe with perfect faith that: God exists; God is perfect in every way, eternal, and the cause of all that exists. All other beings depend upon God for their existence. -

Abbayé and Raba (Talmudic Sages)

INDEX Abbayé and Raba (Talmudic sages), 245 Asher ben Meshullam, 74–75 Abraham, 73, 154–159, 155–156nn52–54, Astronomy, 64n8 158n58, 166–168 Azriel of Gerona Abraham bar Ḥ iyya, 4, 55–58, anti-Maimonideanism and, 36 56–57n90, 62, 64, 67–69, 70, 191 creativity and, 29, 29n5, 32 Abraham ben Axelrad, 186–187, knowledge of God and, 120n53 186n131 Lebanon, explanation of term, 43 Abraham ben David, 3, 135–139, 135n3, logical argumentation and, 160 166–167 philosophic ethos and, 143–144 Abraham ben Isaac, 3, 135n3, 246 Sefer ha-Bahir and, 213n66 Abraham ben Moses ben Maimon, 145 Abraham ibn Ezra Ba‘alé ha-Nefesh (Abraham b. David), on Exod. 20:2, 232 135 on investigating God, 69, 70, 76, 80, Baḥya ibn Pakuda 80n65 divine unity and, 87, 138 Judah ha-Levi and, 129–131 hermeneutical techniques of, 88 on love of God, 89–90 investigating God and, 69–70, 80, 86, philosophic tradition and, 4, 62 137, 151–152 worship and, 93 love of God and, 90, 90n87 Abraham ibn Ḥ asdai, 156n54 on Psalm 100:3, 216 Aggadat Shir ha-Shirim, 46n56, 112, 177 Sefer ha-Bahir and, 198–199 R. Akiva, 116, 117, 118–119 worship and, 93, 198 Alef, interpretation of term, 203–205, B. Berakhot, 145n29, 147–148, 211, 212 148–149n35, 174, 177, 178 Alḥarizi, Judah, 71, 72–73, 164–165, Bere’shit Rabbati, 112, 177 175, 181, 199 Book of Beliefs and Opinions (Saadia ben Almohade invasion, 64 Joseph), 85, 90n88, 126 Anatoli, Jacob, 73–74, 92, 92n93, 247 Book of the Apple (Abraham ibn Animals, human beings vs., 220, 223 Ḥasdai), 156n54 Apple, explanation of term, 47–48, Book of the Commandments (Ḥ efets ben 47n60 Yatsliaḥ), 78–80, 83, 151–152 Arabic language, 4, 61–62n2, 63, 71, 76 Book of the Commandments Aristotle, 6, 19, 249 ( Maimonides), 150, 225, 227–228 Asher ben David Book of the Commandments (Samuel alef, meaning of term, 204 ben Ḥofni), 77–78 created world and, 160–161 on divine unity, 19, 137–139, Canticles. -

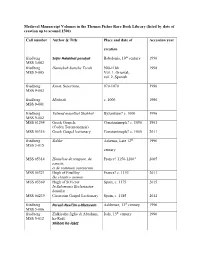

Medieval Manuscript Volumes in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (Listed by Date of Creation up to Around 1500) Call Number Au

Medieval Manuscript Volumes in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (listed by date of creation up to around 1500) Call number Author & Title Place and date of Accession year creation friedberg Sefer Halakhot pesuḳot Babylonia, 10 th century 1996 MSS 3-002 friedberg Ḥamishah ḥumshe Torah 900-1188 1998 MSS 9-005 Vol. 1, Oriental; vol. 2, Spanish. friedberg Kinot . Selections. 970-1070 1996 MSS 9-003 friedberg Mishnah c. 1000 1996 MSS 9-001 friedberg Talmud masekhet Shabbat Byzantium? c. 1000 1996 MSS 9-002 MSS 01244 Greek Gospels Constantinople? c. 1050 1901 (Codex Torontonensis) MSS 05316 Greek Gospel lectionary Constantinople? c. 1050 2011 friedberg Siddur Askenaz, Late 12 th 1996 MSS 3-015 century MSS 05314 Homeliae de tempore, de France? 1150-1200? 2005 sanctis, et de communi sanctorum MSS 05321 Hugh of Fouilloy. France? c. 1153 2011 De claustro animae MSS 03369 Hugh of StVictor Spain, c. 1175 2015 In Salomonis Ecclesiasten homiliæ MSS 04239 Cistercian Gospel Lectionary Spain, c. 1185 2012 friedberg Perush Neviʼim u-Khetuvim Ashkenaz, 13 th century 1996 MSS 5-006 friedberg Zidkiyahu figlio di Abraham, Italy, 13 th century 1996 MSS 5-012 ha-Rofè. Shibole ha-leḳeṭ friedberg David Kimhi. Spain or N. Africa, 13th 1996 MSS 5-010 Sefer ha-Shorashim century friedberg Ketuvim Spain, 13th century 1996 MSS 5-004 friedberg Beʼur ḳadmon le-Sefer ha- 13th century 1996 MSS 3-017 Riḳmah MSS 04404 William de Wycumbe. Llantony Secunda?, c. 1966 Vita venerabilis Roberti Herefordensis 1200 MSS 04008 Liber quatuor evangelistarum Avignon? c. 1220 1901 MSS 04240 Biblia Latina England, c. -

Title Listing of Sixteenth Century Books

Title Listing of Sixteenth Century Books Abudarham, David ben Joseph Abudarham, Fez, De accentibus et orthographia linguae hebraicae, Johannes Reuchlin, Hagenau, Adam Sikhli, Simeon ben Samuel, Thiengen, Adderet Eliyahu, Elijah ben Moses Bashyazi, Constantinople, Ha-Aguddah, Alexander Suslin ha-Kohen of Frankfurt, Cracow, Agur, Jacob Barukh ben Judah Landau, Rimini, Akedat Yitzhak, Isaac ben Moses Arama, Salonika, Aleh Toledot Adam . Kohelet Ya’akov, Baruch ben Moses ibn Baruch, Venice, – Alfasi (Sefer Rav Alfas), Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi (Rif), Constantinople, Alfasi (Hilkhot Rav Alfas), Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi (Rif), Sabbioneta, – Alfasi (Sefer Rav Alfas), Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi (Rif), Riva di Trento, Alphabetum Hebraicum, Aldus Manutius, Venice, c. Amadis de Gaula, Constantinople, c. Amudei Golah (Semak), Isaac ben Joseph of Corbeil, Constantinople, c. Amudei Golah (Semak), Isaac ben Joseph of Corbeil, Cremona, Arba’ah ve’Esrim (Bible), Pesaro, – Arba’ah Turim, Jacob ben Asher, Fano, Arba’ah Turim, Jacob ben Asher, Augsburg, Arba’ah Turim, Jacob ben Asher, Constantinople, De arcanis catholicae veritatis, Pietro Columna Galatinus, Ortona, Arukh, Nathan ben Jehiel, Pesaro, Asarah Ma’amarot, Menahem Azariah da Fano, Venice, Avkat Rokhel, Machir ben Isaac Sar Hasid, Augsburg, Avkat Rokhel, Machir ben Isaac Sar Hasid—Venice, – Avodat ha-Levi, Solomon ben Eliezer ha-Levi, Venice, Ayumah ka-Nidgaloth, Isaac ben Samuel Onkeneira, Constantinople, Ayyalah Sheluhah, Naphtali Hirsch ben Asher Altschuler, Cracow, c. Ayyelet -

1 the Image of Jacob Engraved Upon the Throne: Further Reflection on the Esoteric Doctrine of the German Pietists

1 The Image of Jacob Engraved upon the Throne: Further Reflection on the Esoteric Doctrine of the German Pietists Verily, at this time that which was hidden has been revealed because forgetfulness has reached its final limit; the end of forgetfulness is the beginning of remembrance. Abraham Abulafia,'Or ha-Sekhel, MS Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek 92, fol. 59b I One of the most interesting motifs in the world of classical rabbinic aggadah is that of the image of Jacob engraved on the throne of glory. My intention in this chapter is to examine in detail the utilization of this motif in the rich and varied literature of Eleazar ben Judah of Worms, the leading literary exponent of the esoteric and mystical pietism cultivated by the Kalonymide circle of German Pietists in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The first part of the chapter will investigate the ancient traditions connected to this motif as they appear in sources from Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages in order to establish the basis for the distinctive understanding that evolves in the main circle of German Pietists to be discussed in the second part. As I will argue in detail later, the motif of the image of Jacob has a special significance in the theosophy of the German Pietists, particularly as it is expounded in the case of Eleazar. The amount of attention paid by previous scholarship to this theme is disproportionate in relation to the central place that it occupies in the esoteric ruminations of the Kalonymide Pietists. 1 From several passages in the writings of Eleazar it is clear that the motif of the image of Jacob is covered and cloaked in utter secrecy.