1 the Image of Jacob Engraved Upon the Throne: Further Reflection on the Esoteric Doctrine of the German Pietists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TALMUDIC STUDIES Ephraim Kanarfogel

chapter 22 TALMUDIC STUDIES ephraim kanarfogel TRANSITIONS FROM THE EAST, AND THE NASCENT CENTERS IN NORTH AFRICA, SPAIN, AND ITALY The history and development of the study of the Oral Law following the completion of the Babylonian Talmud remain shrouded in mystery. Although significant Geonim from Babylonia and Palestine during the eighth and ninth centuries have been identified, the extent to which their writings reached Europe, and the channels through which they passed, remain somewhat unclear. A fragile consensus suggests that, at least initi- ally, rabbinic teachings and rulings from Eretz Israel traveled most directly to centers in Italy and later to Germany (Ashkenaz), while those of Babylonia emerged predominantly in the western Sephardic milieu of Spain and North Africa.1 To be sure, leading Sephardic talmudists prior to, and even during, the eleventh century were not yet to be found primarily within Europe. Hai ben Sherira Gaon (d. 1038), who penned an array of talmudic commen- taries in addition to his protean output of responsa and halakhic mono- graphs, was the last of the Geonim who flourished in Baghdad.2 The family 1 See Avraham Grossman, “Zik˙atah shel Yahadut Ashkenaz ‘el Erets Yisra’el,” Shalem 3 (1981), 57–92; Grossman, “When Did the Hegemony of Eretz Yisra’el Cease in Italy?” in E. Fleischer, M. A. Friedman, and Joel Kraemer, eds., Mas’at Mosheh: Studies in Jewish and Moslem Culture Presented to Moshe Gil [Hebrew] (Jerusalem, 1998), 143–57; Israel Ta- Shma’s review essays in K˙ ryat Sefer 56 (1981), 344–52, and Zion 61 (1996), 231–7; Ta-Shma, Kneset Mehkarim, vol. -

ENCYCLOPAEDIA JUDAICA, Second Edition, Volume 2 Lowers of Aristotle

aristotle lowers of Aristotle, at times as his critics, included, during the the question of *creation. Aristotle based his notion that the 13t and 14t centuries – Samuel ibn *Tibbon, Jacob *Anatoli, world is eternal on the nature of time and motion (Physics, Shem Tov ibn *Falaquera, Levi b. Abraham of Villefranche, 8:1–3; Metaphysics, 12:6, 1–2; De Caelo, 1:10–12) and on the Joseph *Kaspi, Zerahiah b. Isaac *Gracian, *Hillel b. Samuel impossibility of assuming a genesis of prime matter (Physics, of Verona, Isaac *Albalag, Moses *Abulafia, *Moses b. Joshua 1:9). In contrast to the Kalām theologians, who maintained the of Narbonne, and *Levi b. Gershom (Gersonides), their most doctrine of temporal creation, the medieval Muslim philoso- outstanding representative; from the 15t to the 17t century – phers interpreted creation as eternal, i.e., as the eternal pro- Simeon b. Ẓemaḥ *Duran, Joseph *Albo, the brothers Joseph cession of forms which emanate from the active or creative and Isaac *Ibn Shem Tov, Abraham *Bibago, *Judah b. Jehiel knowledge of God (see *Emanation). The task with which the Messer Leon, Elijah *Delmedigo, Moses *Almosnino, and Jo- Jewish Aristotelians were faced was either to disprove or to seph Solomon *Delmedigo. (The exact relation of these phi- accept the notion of the world’s eternity. Maimonides offers losophers to Aristotle may be gathered from the entries ap- a survey and refutation of Kalām proofs for creation and ad- pearing under their names.) vances his own theory of temporal creation (Guide, 2:17), for which he indicates the theological motive that miracles are Issues in Jewish Aristotelianism possible only in a universe created by a spontaneous divine Jewish Aristotelianism is a complex phenomenon, the general will (2:25). -

The Role of Hebrew Letters in Making the Divine Visible

"VTSFDIUMJDIFO (SàOEFOTUFIU EJFTF"CCJMEVOH OJDIUJN0QFO "DDFTT[VS 7FSGàHVOH The Role of Hebrew Letters in Making the Divine Visible KATRIN KOGMAN-APPEL hen Jewish figural book art began to develop in central WEurope around the middle of the thirteenth century, the patrons and artists of Hebrew liturgical books easily opened up to the tastes, fashions, and conventions of Latin illu- minated manuscripts and other forms of Christian art. Jewish book designers dealt with the visual culture they encountered in the environment in which they lived with a complex process of transmis- sion, adaptation, and translation. Among the wealth of Christian visual themes, however, there was one that the Jews could not integrate into their religious culture: they were not prepared to create anthropomorphic representations of God. This stand does not imply that Jewish imagery never met the challenge involved in representing the Divine. Among the most lavish medieval Hebrew manu- scripts is a group of prayer books that contain the liturgical hymns that were commonly part of central European prayer rites. Many of these hymns address God by means of lavish golden initial words that refer to the Divine. These initials were integrated into the overall imagery of decorated initial panels, their frames, and entire page layouts in manifold ways to be analyzed in what follows. Jewish artists and patrons developed interesting strategies to cope with the need to avoid anthropomorphism and still to give way to visually powerful manifestations of the divine presence. Among the standard themes in medieval Ashkenazi illuminated Hebrew prayer books (mahzorim)1 we find images of Moses receiving the tablets of the Law on Mount Sinai (Exodus 31:18, 34), commemorated during the holiday of Shavuot, the Feast of Weeks (fig. -

Jewish Culture in the Christian World James Jefferson White University of New Mexico - Main Campus

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 11-13-2017 Jewish Culture in the Christian World James Jefferson White University of New Mexico - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation White, James Jefferson. "Jewish Culture in the Christian World." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/207 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. James J White Candidate History Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Sarah Davis-Secord, Chairperson Timothy Graham Michael Ryan i JEWISH CULTURE IN THE CHRISTIAN WORLD by JAMES J WHITE PREVIOUS DEGREES BACHELORS THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2017 ii JEWISH CULTURE IN THE CHRISTIAN WORLD BY James White B.S., History, University of North Texas, 2013 M.A., History, University of New Mexico, 2017 ABSTRACT Christians constantly borrowed the culture of their Jewish neighbors and adapted it to Christianity. This adoption and appropriation of Jewish culture can be fit into three phases. The first phase regarded Jewish religion and philosophy. From the eighth century to the thirteenth century, Christians borrowed Jewish religious exegesis and beliefs in order to expand their own understanding of Christian religious texts. -

Judaism Confronts...The Big Bang and Evolution Daniel Anderson - Limmud Conference (Dec 2014/Tevet 5775)

Judaism confronts...the Big Bang and Evolution Daniel Anderson - Limmud Conference (Dec 2014/Tevet 5775) 1) The literalist perspective: Lubavitcher Rebbe and Rabbi Dr David Gottlieb The universe is 6 days old and science is wrong ...it was quite a surprise to me to learn that you are still troubled by the problem of the age of the world as suggested by various scientific theories which cannot be reconciled with the Torah view that the world is 5722 years old. I underlined the word theories, for it is necessary to bear in mind, first of all, that science formulates and deals with theories and hypotheses while the Torah deals with absolute truths. These are two different disciplines, where reconciliation is entirely out of place... In short, of all the weak scientific theories, those which deal with the origin of the cosmos and with its dating are (admittedly by the scientists themselves) the weakest of the weak... Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson/Lubavitcher Rebbe (1902-1994), 18th Tevet 5722 [December 25, 1961] Brooklyn, NY The solution to the contradiction between the age of the earth and the universe according to science and the Jewish date of 5755 years since Creation is this: the real age of the universe is 5755 years, but it has misleading evidence of greater age. Rabbi David Gottlieb, PhD in Mathematics, former Professor of Philosophy at John Hopkins University, Senior faculty of Ohr Somayach Yeshiva Evolution is nonsense ...The argument from the discovery of the fossils is by no means conclusive evidence of the great antiquity of the earth.. -

S 5776 Years and Science’S 15.5 Billion Years

Torah’s 5776 years and Science’s 15.5 Billion years Here’s one approach to resolving the Biblical and Scientific Ages of the Universe. There are many ways to resolve this apparent dilemma. Here is one way that many Torah observant Jews approach this question. (It’s an article I wrote a number of years ago when I studied the subject to resolve this issue for myself – Shmuel Veffer) It requires a careful reading of the relevant Torah passages in the original Hebrew and using the Oral Torah to help us understand what many of the terms really mean. A Finite Universe The Torah teaches that the Universe is finite and that there is a first Being we call “God” which exists outside of Time and Space. As Creator, God 1 is distinct from the world, existing on a higher plane. Everything in existence was created by this First Being, including “time,” “space,” “matter,” “energy,” and all things in the spiritual realm, such as souls 2 and angels. Nothing, except God existed before Creation. This concept is derived from the opening sentence of the Torah, “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth” (Genesis 1:1) That nothing existed before Creation is also alluded to by the Torah in that the Torah begins with the letter beth which is closed on three sides. Everything flows forth from the open side. Unique Among Ancient Beliefs The idea that Time and Space are parts of creation is unique among ancient beliefs. The Greek concept, which was the prevalent until the 20th century, held that the universe was unchanging. -

Ashkenaz at the Crossroads of Cultural Transfer II: Tradition and Identity

H-Announce Ashkenaz at the Crossroads of Cultural Transfer II: Tradition and Identity Announcement published by Saskia Doenitz on Tuesday, October 25, 2016 Type: Conference Date: November 28, 2016 to November 30, 2016 Location: Germany Subject Fields: Humanities, Intellectual History, Jewish History / Studies, Popular Culture Studies, Religious Studies and Theology International Conference, November 28-30th 2016 Ashkenaz at the Crossroads of Cultural Transfer II: Tradition and Identity Institute of Judaic Studies, Goethe-University, Frankfurt am Main Seminarsaal, 10th floor, Juridicum, Senckenberganlage 31 (Campus Bockenheim) Program Monday, November 28th 09:15-10:00 a.m. Saskia Dönitz, Elisabeth Hollender, Rebekka Voß (Frankfurt): Welcome and Introduction 10:00-10:30 a.m. Coffee Session 1 10:30-11:10 a.m. Elisheva Baumgarten (Jerusalem): Biblical Models Transformed: A Useful Key to Everyday Life in Medieval Ashkenaz 11:10-11:50 a.m. Sarah Japhet (Jerusalem): Biblical Exegesis as a Vehicle of Cultural Adaptation and Integration: A Case Study 11:50-12:30 p.m. Oren Roman (Düsseldorf): Tanakh-Epos: Early Modern Ashkenazic Retellings of Biblical Scenes 12:30-02:00 p.m. Lunch Break Citation: Saskia Doenitz. Ashkenaz at the Crossroads of Cultural Transfer II: Tradition and Identity. H-Announce. 10-25-2016. https://networks.h-net.org/node/73374/announcements/149260/ashkenaz-crossroads-cultural-transfer-ii-tradition-and-identity Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. 1 H-Announce Session 2 02:00-02:40 p.m. Talya Fishman (Philadelphia): Cultural Functions of Masorah in Medieval Ashkenaz 02:40-03:20 p.m. -

1 Beginning the Conversation

NOTES 1 Beginning the Conversation 1. Jacob Katz, Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times (New York: Schocken, 1969). 2. John Micklethwait, “In God’s Name: A Special Report on Religion and Public Life,” The Economist, London November 3–9, 2007. 3. Mark Lila, “Earthly Powers,” NYT, April 2, 2006. 4. When we mention the clash of civilizations, we think of either the Spengler battle, or a more benign interplay between cultures in individual lives. For the Spengler battle, see Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). For a more benign interplay in individual lives, see Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999). 5. Micklethwait, “In God’s Name.” 6. Robert Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). “Interview with Robert Wuthnow” Religion and Ethics Newsweekly April 26, 2002. Episode no. 534 http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week534/ rwuthnow.html 7. Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity, 291. 8. Eric Sharpe, “Dialogue,” in Mircea Eliade and Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of Religion, first edition, volume 4 (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 345–8. 9. Archbishop Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (London: SPCK, 2006). 10. Lily Edelman, Face to Face: A Primer in Dialogue (Washington, DC: B’nai B’rith, Adult Jewish Education, 1967). 11. Ben Zion Bokser, Judaism and the Christian Predicament (New York: Knopf, 1967), 5, 11. 12. Ibid., 375. -

“Arba 'Ah Turim of Rabbi Jacob Ben Asher on Medical Ethics, ” Rabbi David Fink, Ph.D

Arba`ah Turim of Rabbi Jacob ben Asher on Medical Ethics Rabbi David Fink, Ph.D. Rabbi Jacob ben Asher was a leading halachic authority of the early part of the fourteenth century. As a young man he accompanied his father, Rabbi Asher ben Yechiel (Rosh), from Germany to Spain. In Toledo he wrote a number of basic halachic and exegetical works. The most important of these are the Arba`ah Turim, which later became the basis of Rabbi Joseph Karo’s Shulchan Aruch. The following passage is taken from section 336 of the second book (Yoreh De`ah) of the Arba`ah Turim. It deals with the obligations of medical practitioners. Rabbi Jacob’s opinions on this topic became the subject of commentary and analysis by the leading halachic scholars of subsequent generations. At the School of Rabbi Ishmael it was taught that the verse “And he shall heal (Ex. 21:19)” implies that the physician is permitted to heal.1 One should not disregard pain for fear of making a mistake and inadvertently killing the patient. Rather one must be exceedingly cautious as is proper in any capital case. Further, one should not say that if God has smitten the patient, it is improper to heal him, it being unnatural for mortals to restore health, even though they are accustomed to do so.2 Thus it says, “Yet in his disease he sought not to the Lord, but to the physicians (2 Chr. 16:12)”. From this we learn that the physician is permitted to heal and that healing is a part of the commandment of lifesaving. -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. -

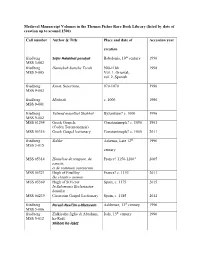

Medieval Manuscript Volumes in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (Listed by Date of Creation up to Around 1500) Call Number Au

Medieval Manuscript Volumes in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (listed by date of creation up to around 1500) Call number Author & Title Place and date of Accession year creation friedberg Sefer Halakhot pesuḳot Babylonia, 10 th century 1996 MSS 3-002 friedberg Ḥamishah ḥumshe Torah 900-1188 1998 MSS 9-005 Vol. 1, Oriental; vol. 2, Spanish. friedberg Kinot . Selections. 970-1070 1996 MSS 9-003 friedberg Mishnah c. 1000 1996 MSS 9-001 friedberg Talmud masekhet Shabbat Byzantium? c. 1000 1996 MSS 9-002 MSS 01244 Greek Gospels Constantinople? c. 1050 1901 (Codex Torontonensis) MSS 05316 Greek Gospel lectionary Constantinople? c. 1050 2011 friedberg Siddur Askenaz, Late 12 th 1996 MSS 3-015 century MSS 05314 Homeliae de tempore, de France? 1150-1200? 2005 sanctis, et de communi sanctorum MSS 05321 Hugh of Fouilloy. France? c. 1153 2011 De claustro animae MSS 03369 Hugh of StVictor Spain, c. 1175 2015 In Salomonis Ecclesiasten homiliæ MSS 04239 Cistercian Gospel Lectionary Spain, c. 1185 2012 friedberg Perush Neviʼim u-Khetuvim Ashkenaz, 13 th century 1996 MSS 5-006 friedberg Zidkiyahu figlio di Abraham, Italy, 13 th century 1996 MSS 5-012 ha-Rofè. Shibole ha-leḳeṭ friedberg David Kimhi. Spain or N. Africa, 13th 1996 MSS 5-010 Sefer ha-Shorashim century friedberg Ketuvim Spain, 13th century 1996 MSS 5-004 friedberg Beʼur ḳadmon le-Sefer ha- 13th century 1996 MSS 3-017 Riḳmah MSS 04404 William de Wycumbe. Llantony Secunda?, c. 1966 Vita venerabilis Roberti Herefordensis 1200 MSS 04008 Liber quatuor evangelistarum Avignon? c. 1220 1901 MSS 04240 Biblia Latina England, c. -

Preview Index

INDEX Bacharach. Hava/Eva, 134 A bat, meaning of, 303 n. 63 Aberlin, Rachel Mishan, 170, 196 Bat Ha-Levi of Baghdad, 54, 62 abolitionist movement, 242, 268–269 Beatrice de Luna, see Nasi, Gracia Abrabanel, Benvenida, 104, 107–108, 121, Beila of the Blessed Hands, 224 123, 125, 127 Bellina of Venice, Madonna, 105, 109 Ackerman Paula, 275 Benayah, Miriam, 188 adultery Berenice, 30 in biblical law, 43 Beruriah of Palestine, xi, 26–28, 30, 39, in rabbinic law, 43 284 n. 284 in Christian Spain, 96 betrothal, gaonic, 64 Aguilar, Grace, 204–205, 206, 223, 225, Bible Teacher of Fustat, 54–55, 61, 64, 66 231, 232, 250 “bitter water” ordeal, 43, 285 n. 62 agunah problem, 122, 154, 229, 266, 300 n. blessing of the bride, 68 98 Brandeau, Esther, 240, 244 Ahimaaz ben Paltiel, 103–104 Brazilian Jewry, 238–239 Alexander, Rebecca, 271 bride price/payment Aliyot by women, 101 Bible, 12 Allegra of Majorca, 77 Elephantine, 6, 12 Alvares, Judith Baruch, 268 rabbinc era, 40 amulets and charms, use of business women in antiquity, 4, 19, 20 Elephantine, 5 in rabbinic era, 46 Babatha archive, 5, 223 in Islamic era, 71 Christian Europe, 87–88, 97 in hasidic courts, 234 Italy, 117–118 see also magic Ashkenaz, 149, 150 Anna the Hebrew of Rome, 108, 118 Ottoman Empire, 185, 186 Anthony, Susan B., 260 early modern Europe, 223 anti-Semitism United States, 263 Christian, 74–76, 130–131 Muslim, 49–50 C American Jewry, origins, 239–243 Cairo Genizah, 51 Arabian and Yemenite Jewry, 49–50 Canadian Jewry, origins, 240–241 Arnstein, Fanny von, 202, 205–206 candlelighting, commandment of, 38, 159, d’Arpino, Anna, 108, 127 232 artisans, Ottoman Empire, 186 captives, 62, 311 n.