Compassion for All Creatures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Contemporary Ethics Part 9: the Written and Oral Torah by Rabbi Dr Moshe Freedman, New West End Synagogue

Vayetze Vol.31 No.11.qxp_Layout 1 31/10/2018 10:58 Page 4 Jewish Contemporary Ethics Part 9: The Written and Oral Torah by Rabbi Dr Moshe Freedman, New West End Synagogue The last article introduced animals which were “ritually clean” and just one the idea that God’s Divine pair of animals which were “not ritually clean” morality is not simply into the Ark (Bereishit 7:2). The Talmud explains imposed on humanity, that Noach studied the laws of the kashrut of but requires an eternal animals, and that he needed more kosher covenant and ongoing animals in order to offer them to God after leaving relationship between God the ark (Zevachim 116a). and mankind. The next section of this series will try to analyse the nature, The Talmud notes that Avraham himself deduced meaning and mechanics of that covenant. both the existence of God and the mitzvot, and kept the entire Torah (Yoma 28b). Avraham then When we refer to ‘the Torah’ we often mean the taught Torah to his family, who also kept its laws Five Books of Moshe. The word itself derives (see Beresihit 18:19 and 26:5). This generates a from the Hebrew root hry, which in this form number of fascinating conundrums where the means to guide or teach (see Vayikra 10:11). Yet actions of our forefathers appear to contradict the commentators write that the concept of ‘the Torah law. While a detailed resolution lies beyond Torah’ is much deeper and more complex. the scope of this series, it shows that Avraham not only recognised the Unity of God, but that he We may be used to thinking that the Torah was was the progenitor and advocate of pre-Sinaitic given to the Jewish people via Moshe at Mount Torah, which was Monotheistic. -

Toronto Torah Beit Midrash Zichron Dov

בס“ד Toronto Torah Beit Midrash Zichron Dov Parshat Chayei Sarah 22 Marcheshvan 5770/October 30, 2010 Vol.2 Num. 9 Havdalah: Recuperation or Preparation? Dovid Zirkind world with spirituality (the soul), putting וינפש, כיון ששבת ווי אבדה נפש. As a general rule, time-bound mitzvot are required of men in Jewish law and into place the final piece in the creation “Reish Lakish said: G-d gives man an not women. However, one notable of the world. Without Shabbat, all of additional soul before Shabbat and takes exception to this rule is Shabbat. Our creation would not have had the it from him after Shabbat, as it says in the Rabbis teach us, based on the independent strength to continue verse, „He rested, Vayinafash.’ Once the descriptions of Shabbat in the Torah, existing. Once there was a Shabbat, an resting is complete, woe (Vay), for he has that anyone who is obligated in the infusion of spirituality, the world was lost his soul (Nefesh).” prohibitions of Shabbat is likewise complete - and therefore able to commanded to observe its active We work for seven days in anticipation of continue. mitzvot. This explains why women are Shabbat, and so havdalah can be seen as Along the same lines, the Zohar writes obligated in kiddush despite its time- a bittersweet moment in our week. We that the brit of a baby boy must be on bound nature. The Rambam writes are thrilled to have Shabbat, and the the 8th day because this insures that (Hilchot Shabbat 29:1) that women are break and the enhanced spirituality that every baby will have already lived a obligated in havdalah based on the comes with it, but the loss of the Shabbat and therefore been given his same principle. -

Must a Coronavirus Carrier Disclose That Information?

Coronavirus Israel News Opinion Middle East Diaspora U.S. Politics WORLD NEWS Login Advertisement Judaism Gaza News BDS Antisemitism OMG Health & Science Business & Tech Premium Food MarchTak eOf theThe Living International IQ Test The o∆cial IQ test used around the world (Average IQ score: 100). International IQ Test Jerusalem Post Judaism Must a coronavirus carrier disclose that Subscribe for ou newsletter information? Your e-mail addres Find out a Rabbi's perspective on this newly relevant question. By subscribing I accept t By SHLOMO BRODY APRIL 3, 2020 06:25 Hot Opinion A broken econ coronavirus pandemic B Keeping eyes o virus but the beauty of I KATZ A coronavirus- – opinion By LIAT COL Olmert to 'Post Gantz really thinking? B Hell hath no fu scorned – opinion By RU 'Imagine if we had, God forbid, tested positive and had further exposed our neighbor' (photo credit: TNS) One of the many dilemmas that have emerged from the coronavirus pandemic is the question of confidentiality. When a person tests positive for COVID-19, do they have a halachic obligation to inform those that they were in contact with over the Advertisement previous two weeks? Read More Related Articles Chinese coronavirus testing facility to arrive in Israel by next week Israeli scientist claims he is two-thirds the way to COVID-19 vaccine Recommended by This could include family members, neighbors, colleagues and even shopkeepers in which one spent an extended period of time together. I believe that the answer is yes and that there is no reason why people should feel ashamed in sharing this information with those who need to know. -

1. Agudas Shomrei Hadas Rabbi Kalman Ochs 320 Tweedsmuir Ave

1. Agudas Shomrei Hadas Rabbi Kalman Ochs 320 Tweedsmuir Ave Suite 207 Toronto, Ontario M5P 2Y3 Canada (416)357-7976 [email protected] 2. Atlanta Kashrus – Peach Kosher 1855 LaVista Road N.E. Atlanta, GA 30329 404-634-4063 www.kosheratlanta.org Rabbi Reuven Stein [email protected] 404-271-2904 3. Beth Din of Johannesburg Rabbi Dovi Goldstein POB 46559, Orange Grove 2119 Johannesburg, South Africa 010-214-2600 [email protected] 4. BIR Badatz Igud Rabbonim 5 Castlefield Avenue Salford, Manchester, M7 4GQ, United Kingdom +44-161-720-8598 www.badatz.org Rabbi Danny Moore 44-161-720-8598 fax 44-161-740-7402 [email protected] 5. Blue Ribbon Kosher Rabbi Sholem Fishbane 2701 W. Howard Chicago, IL 60645 773-465-3900 [email protected] crckosher.org 6. British Colombia -BC Kosher - Kosher Check Rabbi Avraham Feigelstock 401 - 1037 W. Broadway Vancouver, B.C. V6H 1E3 CANADA 604-731-1803 fax 604-731-1804 [email protected] 7. Buffalo Va’ad Rabbi Eliezer Marcus 49 Barberry Lane Buffalo, NY 11421 [email protected] 716-534-0230 8. Caribbean Kosher Rabbi Mendel Zarchi 18 Calle Rosa Carolina, PR 00979 787.253.0894 [email protected] 9. Central California Kosher Rabbi Levy Zirkind 1227 E. Shepherd Ave. Fresno, CA 93720 559-288-3048 [email protected] centralcaliforniakosher.org 10. Chanowitz, Rabbi Ben Zion 15 North St. Monticello, NY 12701 [email protected] 845-321-4890 11. Chelkas Hakashrus of Zichron Yaakov 131 Iris Road Lakewood, NJ 08701 732 901-6508 Rabbi Yosef Abicasis [email protected] 12. -

Judaism Confronts...The Big Bang and Evolution Daniel Anderson - Limmud Conference (Dec 2014/Tevet 5775)

Judaism confronts...the Big Bang and Evolution Daniel Anderson - Limmud Conference (Dec 2014/Tevet 5775) 1) The literalist perspective: Lubavitcher Rebbe and Rabbi Dr David Gottlieb The universe is 6 days old and science is wrong ...it was quite a surprise to me to learn that you are still troubled by the problem of the age of the world as suggested by various scientific theories which cannot be reconciled with the Torah view that the world is 5722 years old. I underlined the word theories, for it is necessary to bear in mind, first of all, that science formulates and deals with theories and hypotheses while the Torah deals with absolute truths. These are two different disciplines, where reconciliation is entirely out of place... In short, of all the weak scientific theories, those which deal with the origin of the cosmos and with its dating are (admittedly by the scientists themselves) the weakest of the weak... Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson/Lubavitcher Rebbe (1902-1994), 18th Tevet 5722 [December 25, 1961] Brooklyn, NY The solution to the contradiction between the age of the earth and the universe according to science and the Jewish date of 5755 years since Creation is this: the real age of the universe is 5755 years, but it has misleading evidence of greater age. Rabbi David Gottlieb, PhD in Mathematics, former Professor of Philosophy at John Hopkins University, Senior faculty of Ohr Somayach Yeshiva Evolution is nonsense ...The argument from the discovery of the fossils is by no means conclusive evidence of the great antiquity of the earth.. -

S 5776 Years and Science’S 15.5 Billion Years

Torah’s 5776 years and Science’s 15.5 Billion years Here’s one approach to resolving the Biblical and Scientific Ages of the Universe. There are many ways to resolve this apparent dilemma. Here is one way that many Torah observant Jews approach this question. (It’s an article I wrote a number of years ago when I studied the subject to resolve this issue for myself – Shmuel Veffer) It requires a careful reading of the relevant Torah passages in the original Hebrew and using the Oral Torah to help us understand what many of the terms really mean. A Finite Universe The Torah teaches that the Universe is finite and that there is a first Being we call “God” which exists outside of Time and Space. As Creator, God 1 is distinct from the world, existing on a higher plane. Everything in existence was created by this First Being, including “time,” “space,” “matter,” “energy,” and all things in the spiritual realm, such as souls 2 and angels. Nothing, except God existed before Creation. This concept is derived from the opening sentence of the Torah, “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth” (Genesis 1:1) That nothing existed before Creation is also alluded to by the Torah in that the Torah begins with the letter beth which is closed on three sides. Everything flows forth from the open side. Unique Among Ancient Beliefs The idea that Time and Space are parts of creation is unique among ancient beliefs. The Greek concept, which was the prevalent until the 20th century, held that the universe was unchanging. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Introduction to the Purpose of Man in the World

INTRODUCTION TO THE PURPOSE OF MAN IN THE WORLD he Morasha syllabus features a series of classes addressing the purpose of man in Tthe world. These shiurim address fundamental principles of Jewish philosophy including the relationship of the body and the soul, free will, the centrality of chesed (loving kindness), hashgachah pratit (Divine providence) and striving to emulate God. However, these principles revolve around even more basic issues that need to be explored first: What is the purpose of existence? Is there a purpose of man in this world, and if so, what is it? Why did God place us in a physical, material world? This shiur provides an approach to these questions which then serves as the underpinning for subsequent classes on fundamental Jewish principles. The evolutionary biologist and atheist Richard Dawkins (in River out of Eden) has the following to say about purpose: The universe that we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference. Judaism teaches that purpose is inherent to the world, and inherent to human existence. As the US National Academy of Sciences asserts (Teaching About Evolution and the Nature of Science), there is little room for science in this discussion: “Whether there is a purpose to the universe or a purpose for human existence are not questions for science.” In stark contrast to Dawkins, this class presents the Jewish outlook on purpose, and will address the following questions: Why did God create the world? Why are we here? Was the world created for God’s sake, or for ours? What are the “important things in life?” Do I have an individual mission in life? 1 Purpose of Man in the World INTRODUCTION TO THE PURPOSE OF MAN IN THE WORLD Class Outline: Introduction: In Only Nine Million Years We’ll Reach Kepler-22B Section I: Why Did God Create the World? Part A. -

Directory of Kosher Certifying Agencies

Directory of Kosher Certifying Agencies - Worldwide As a public service, the Chicago Rabbinical Council is presenting a list of common acceptable kosher symbols and their agency’s contact information. Note: There are more than 700 kosher certifying agencies around the world, making it impossible to list all of them. The fact that a particular agency does not appear on this list does not imply that the cRc has determined it to be substandard. UNITED STATES California Igud Hakashrus of Los Angeles (Kehillah Kosher) 186 North Citrus Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90036 (323) 935-8383 Rabbi Avraham Teichman Rabbinical Council of California (RCC) 617 South Olive St. #515, Los Angeles, CA 90014 (213) 489-8080 Rabbi Nissim Davidi Colorado Scroll K / Vaad Hakashrus of Denver 1350 Vrain St. Denver, CO 80204 (303) 595-9349 Rabbi Moshe Heisler District of Columbia Vaad HaRabanim of Greater Washington 7826 Eastern Ave. NW, Suite LL8 Washington DC 20012 (202) 291-6052 Rabbi Binyamin Sanders Florida A service of the Kashrus Division of the Chicago Rabbinical Council – Serving the world! 1 www.crcweb.org Updated: 1/03/2005 Kosher Miami The Vaad HaKashrus of Miami-Dade PO Box 403225 Miami, FL 33140-1225 Tel: (786) 390-6620 Rabbi Yehuda Kravitz Florida K and Florida Kashrus Services 642 Green Meadow Ave. Maitland, FL 32751 (407) 644-2500 Rabbi Sholom B. Dubov South Palm Beach Vaad (ORB) 5840 Sterling Rd. #256 Hollywood, FL 33021 (305) 534-9499 Rabbi Manish Spitz Georgia Atlanta Kashrus Commission 1855 La Vista Rd., Atlanta, GA 30329 (404) 634-4063 Rabbi Reuven Stein Illinois Chicago Rabbinical Council (cRc) 2701 W. -

Reliable Certifications

unsaved:///new_page_1.htm Reliable Certifications Below are some Kashrus certifications KosherQuest recommends catagorized by country. If you have a question on a symbol not listed below, feel free to ask . Click here to download printable PDF and here to download a printable card. United States of America Alaska Alaska kosher-Chabad of Alaska Congregation Shomrei Ohr 1117 East 35th Avenue Anchorage, Ak 99508 Tel: (907) 279-1200 Fax: (907) 279-7890 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.lubavitchjewishcenter.org Rabbi Yosef Greenberg Arizona Congregation Chofetz Chayim Southwest Torah Institute Rabbi Israel Becker 5150 E. Fifth St. Tuscon, AZ 85711 Cell: (520) 747-7780 Fax: (520) 745-6325 E-mail: [email protected] Arizona K 2110 East Lincoln Drive Phoenix, AZ 85016 Tel: (602) 944-2753 Cell: (602) 540-5612 Fax: (602) 749-1131 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.chabadaz.com Rabbi Zalman levertov, Kashrus Administrator Page 1 unsaved:///new_page_1.htm Chabad of Scottsdale 10215 North Scottsdale Road Scottsdale, AZ 85253 Tel: (480) 998-1410 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.chabadofscottsdale.org Rabbi Yossi Levertov, Director Certifies: The Scottsdale Cafe Deli & Market Congregation Young Israel & Chabad 2443 East Street Tuscon, AZ 85719 Tel: (520) 326-8362, 882-9422 Fax: (520) 327-3818 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.chabadoftuscon.com Rabbi Yossie Y. Shemtov Certifies: Fifth Street Kosher Deli & Market, Oy Vey Cafe California Central California Kosher (CCK) Chabad of Fresno 1227 East Shepherd Ave. Fresno, CA 93720 Tel: (559) 435-2770, 351-2222 Fax: (559) 435-0554 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.chabadfresno.com Rabbi Levy I. -

Kosher Guidelines Manual VEGETABLES

Houston Kashruth Association : Kosher Guidelines Manual This manual serves as an addendum to all client contracts and is a reflection of HKA policies. It must be stated once again that all ingredients and food products must be pre approved by an HKA rabbinic Supervisor and the fact that the guidelines may declare that the item is acceptable does not supersede the need for rabbinic approval. VEGETABLES 1. Artichokes - Fresh, frozen and canned artichokes are not to be used without reliable hashgacha with the exception of artichoke bottoms. All artichoke bottoms are permissible when packed in water, with exception of canned product from China. 2. Asparagus – Green – Fresh must have the tips cut off. Canned & frozen only with a reliable Hashgacha. 3. Asparagus – White- All are permissible without further checking after rinsing with water. Canned & frozen only with a reliable Hashgacha. 4. Barley - (Raw Dry) - Barley may become infested at the food warehouse or retail store or even in ones own home due to prevailing conditions such as humidity, temperature and other insect infestation. As such, one should always make a cursory inspection of the barley before purchasing (if possible) and before use, the barley should be placed in a bowl of cold water for a short time to remove any possible insects. 5. Beans(Canned) - Requires a reliable hashgacha. 6. Beans (Green Beans and String Beans) Fresh - A general inspection is needed to rule out obvious infestation.All frozen are acceptable. Canned require a reliable hashgacha. 7. Beans (Raw Dry)- Dried do not require kosher supervision unless flavorings are added. -

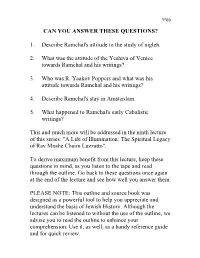

1. Describe Ramchal's Attitude to the Study of Nigleh

c"qa CAN YOU ANSWER THESE QUESTIONS? 1. Describe Ramchal's attitude to the study of nigleh. 2. What was the attitude of the Yeshiva of Venice towards Ramchal and his writings? 3. Who was R. Yaakov Poppers and what was his attitude towards Ramchal and his writings? 4. Describe Ramchal's stay in Amsterdam. 5. What happened to Ramchal's early Cabalistic writings? This and much more will be addressed in the ninth lecture of this series: "A Life of Illumination: The Spiritual Legacy of Rav Moshe Chaim Luzzatto". To derive maximum benefit from this lecture, keep these questions in mind, as you listen to the tape and read through the outline. Go back to these questions once again at the end of the lecture and see how well you answer them. PLEASE NOTE: This outline and source book was designed as a powerful tool to help you appreciate and understand the basis of Jewish History. Although the lectures can be listened to without the use of the outline, we advise you to read the outline to enhance your comprehension. Use it, as well, as a handy reference guide and for quick review. THE EPIC OF THE ETERNAL PEOPLE Presented by Rabbi Shmuel Irons Series IX Lecture #9 A LIFE OF ILLUMINATION: THE SPIRITUAL LEGACY OF RAV MOSHE CHAIM LUZZATTO I. The Controversial Mystic A. 'c ippgi xy`a ,l"z ,gny ip` mbe ,zelbpa ixt iziyr ik z"k gny xy` izi`x (1 zpek ily riaba ip` ygpn j` .ytp zaiyne dninz dlek ik ,dyecwd ezxez iwlg lka el did xak zelbpa iwqr dyere zexzqpd gipn iziid ilele ,de`zn did dfl xy` z"kd iziid `l eil` aexw iziid ilel ik ,z"k zxcd z`n wegx izeid