Luzzatto's Derech Hashem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 'Like Iron to a Magnet': Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence David Sclar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/380 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence By David Sclar A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 David Sclar All Rights Reserved This Manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Prof. Jane S. Gerber _______________ ____________________________________ Date Chair of the Examining Committee Prof. Helena Rosenblatt _______________ ____________________________________ Date Executive Officer Prof. Francesca Bregoli _______________________________________ Prof. Elisheva Carlebach ________________________________________ Prof. Robert Seltzer ________________________________________ Prof. David Sorkin ________________________________________ Supervisory Committee iii Abstract “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence by David Sclar Advisor: Prof. Jane S. Gerber This dissertation is a biographical study of Moses Hayim Luzzatto (1707–1746 or 1747). It presents the social and religious context in which Luzzatto was variously celebrated as the leader of a kabbalistic-messianic confraternity in Padua, condemned as a deviant threat by rabbis in Venice and central and eastern Europe, and accepted by the Portuguese Jewish community after relocating to Amsterdam. -

Jewish Contemporary Ethics Part 9: the Written and Oral Torah by Rabbi Dr Moshe Freedman, New West End Synagogue

Vayetze Vol.31 No.11.qxp_Layout 1 31/10/2018 10:58 Page 4 Jewish Contemporary Ethics Part 9: The Written and Oral Torah by Rabbi Dr Moshe Freedman, New West End Synagogue The last article introduced animals which were “ritually clean” and just one the idea that God’s Divine pair of animals which were “not ritually clean” morality is not simply into the Ark (Bereishit 7:2). The Talmud explains imposed on humanity, that Noach studied the laws of the kashrut of but requires an eternal animals, and that he needed more kosher covenant and ongoing animals in order to offer them to God after leaving relationship between God the ark (Zevachim 116a). and mankind. The next section of this series will try to analyse the nature, The Talmud notes that Avraham himself deduced meaning and mechanics of that covenant. both the existence of God and the mitzvot, and kept the entire Torah (Yoma 28b). Avraham then When we refer to ‘the Torah’ we often mean the taught Torah to his family, who also kept its laws Five Books of Moshe. The word itself derives (see Beresihit 18:19 and 26:5). This generates a from the Hebrew root hry, which in this form number of fascinating conundrums where the means to guide or teach (see Vayikra 10:11). Yet actions of our forefathers appear to contradict the commentators write that the concept of ‘the Torah law. While a detailed resolution lies beyond Torah’ is much deeper and more complex. the scope of this series, it shows that Avraham not only recognised the Unity of God, but that he We may be used to thinking that the Torah was was the progenitor and advocate of pre-Sinaitic given to the Jewish people via Moshe at Mount Torah, which was Monotheistic. -

Adas Israel Congregation June 2017 / Sivan–Tammuz 5777 Chronicle

Adas Israel Congregation June 2017 / Sivan–Tammuz 5777 Chronicle Join us for our annual cantorial concert featuring the Argen-Cantors Chronicle • May 2017 • 1 The Chronicle Is Supported in Part by the Ethel and Nat Popick Endowment Fund clergycorner From the President By Debby Joseph Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt In my early years of learning meditation I studied with Rabbi David Zeller (z”l), at Yakar, a wonderful synagogue in the heart of Jerusalem. I would go to his classes once a week and listen with strong intention to try to understand the practice of meditation, a practice that was changing my everyday life. During the past two years, when people Rabbi Zeller would talk often about the concept of devekut (attachment to learned that I was president of Adas Israel God) that the Hasidic masters had brought alive from teachings in the Zohar: Congregation, they inevitably cracked a “If you are already full, there is no room for God. Empty yourself like a vessel.” joke about feeling sorry for me. Never has I would try my hardest to understand what this meant, but I could not grasp that sentiment been further from the truth. I how to embody this concept, how to make it true to my own experience. have relished serving in this role. I have met How do you empty yourself? What does that feel like? many people, shared many experiences, For many years, in my own spiritual practice, I committed myself to learning and the feelings that permeated all that has meditation, sitting for 5, 10, 20, 30 minutes in silent meditation several times happened during my tenure make up one of a week. -

Introduction to the Purpose of Man in the World

INTRODUCTION TO THE PURPOSE OF MAN IN THE WORLD he Morasha syllabus features a series of classes addressing the purpose of man in Tthe world. These shiurim address fundamental principles of Jewish philosophy including the relationship of the body and the soul, free will, the centrality of chesed (loving kindness), hashgachah pratit (Divine providence) and striving to emulate God. However, these principles revolve around even more basic issues that need to be explored first: What is the purpose of existence? Is there a purpose of man in this world, and if so, what is it? Why did God place us in a physical, material world? This shiur provides an approach to these questions which then serves as the underpinning for subsequent classes on fundamental Jewish principles. The evolutionary biologist and atheist Richard Dawkins (in River out of Eden) has the following to say about purpose: The universe that we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference. Judaism teaches that purpose is inherent to the world, and inherent to human existence. As the US National Academy of Sciences asserts (Teaching About Evolution and the Nature of Science), there is little room for science in this discussion: “Whether there is a purpose to the universe or a purpose for human existence are not questions for science.” In stark contrast to Dawkins, this class presents the Jewish outlook on purpose, and will address the following questions: Why did God create the world? Why are we here? Was the world created for God’s sake, or for ours? What are the “important things in life?” Do I have an individual mission in life? 1 Purpose of Man in the World INTRODUCTION TO THE PURPOSE OF MAN IN THE WORLD Class Outline: Introduction: In Only Nine Million Years We’ll Reach Kepler-22B Section I: Why Did God Create the World? Part A. -

The Exalted Rebbe הצדיק הנשגב

THE EXALTED REBBE הצדיק הנשגב YESHUA IN LIGHT OF THE CHASSIDIC CONCEPTS OF DEVEKUT AND TZADDIKISM הקדמה לרעיון הדבקות בחסידות ויחסו למשיחיות ישוע THE EXALTED REBBE AN INTRODUCTION TO THE CONCEPT OF DEVEKUT AND TZADDIKISM IN CHASIDIC THOUGHT TOBY JANICKI Jewish critics of Messianic Judaism and the New Testament will often raise the argument that the Hebrew Scriptures do not set a precedent for the concept of an intercessor who stands between God and man. In other words, the idea that we need Messiah Yeshua to be the one to lead us to the Father and intercede on our behalf is not biblical. These critics state that we can approach God on our own faith and merit with no need for anyone to be a go-between. In their minds such an idea is idolatrous and completely foreign to Judaism. However, the talmudic sages of Israel developed the idea of the need for an intercessor in the con- cept of the tzaddik (“righteous one”). They, along with the later Chasidic movement, found proof for the need for an intermediary in the Torah and the rest of the Scriptures. By examining the tzaddik within Judaism we can not only defend our faith in the Master but we can also better understand His role from a Torah perspective. THE TZADDIK A true .(צדק ,is derived from the Hebrew word for “righteousness” (tzedek (צדיק) The word tzaddik tzaddik is a sinless person. Tzaddik has the sense of “one whose conduct is found to be beyond re- proach by the divine Judge.”1 According to the New Testament, there is no such person, “for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God,”2 the only exception being Yeshua of Nazareth, who was “tempted in all things as we are, yet without sin.”3 From apostolic reckoning and the perspective of Messianic faith, Yeshua is the only true tzaddik. -

The Archetype of the Tzaddiq in Hasidic Tradition

THE ARCHETYPE OF THE TZADDIQ IN HASIDIC TRADITION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA IN CONJUNCTION wlTH THE DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY YA'QUB IBN YUSUF August4, 1992 National Library B¡bliothèque nat¡onale E*E du Canada Acquisitions and D¡rection des acquisilions et B¡bliographic Services Branch des services bibliograPhiques 395 Wellinolon Slreêl 395, rue Wellington Oflawa. Oñlario Ottawa (Ontario) KlA ON4 K1A ON4 foùt t¡te vat¡e ¡élëte^ce Ou l¡te Nate élëtenæ The author has granted an L'auteur a accordé une licence irrevocable non-exclusive licence irrévocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of permettant à la Bibliothèque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationale du Canada de distribute or sell cop¡es of reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa thèse in any form or format, making de quelque manière et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette thèse à la disposition des personnes intéressées. The author retains ownership of L'auteur conserve la propriété du the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qui protège sa Neither the thesis nor substantial thèse. Ni la thèse ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiels de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent être imprimés ou his/her permission. autrement reproduits sans son autorisation, ïsBN ø-315-7796Ø-S -

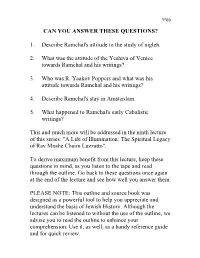

1. Describe Ramchal's Attitude to the Study of Nigleh

c"qa CAN YOU ANSWER THESE QUESTIONS? 1. Describe Ramchal's attitude to the study of nigleh. 2. What was the attitude of the Yeshiva of Venice towards Ramchal and his writings? 3. Who was R. Yaakov Poppers and what was his attitude towards Ramchal and his writings? 4. Describe Ramchal's stay in Amsterdam. 5. What happened to Ramchal's early Cabalistic writings? This and much more will be addressed in the ninth lecture of this series: "A Life of Illumination: The Spiritual Legacy of Rav Moshe Chaim Luzzatto". To derive maximum benefit from this lecture, keep these questions in mind, as you listen to the tape and read through the outline. Go back to these questions once again at the end of the lecture and see how well you answer them. PLEASE NOTE: This outline and source book was designed as a powerful tool to help you appreciate and understand the basis of Jewish History. Although the lectures can be listened to without the use of the outline, we advise you to read the outline to enhance your comprehension. Use it, as well, as a handy reference guide and for quick review. THE EPIC OF THE ETERNAL PEOPLE Presented by Rabbi Shmuel Irons Series IX Lecture #9 A LIFE OF ILLUMINATION: THE SPIRITUAL LEGACY OF RAV MOSHE CHAIM LUZZATTO I. The Controversial Mystic A. 'c ippgi xy`a ,l"z ,gny ip` mbe ,zelbpa ixt iziyr ik z"k gny xy` izi`x (1 zpek ily riaba ip` ygpn j` .ytp zaiyne dninz dlek ik ,dyecwd ezxez iwlg lka el did xak zelbpa iwqr dyere zexzqpd gipn iziid ilele ,de`zn did dfl xy` z"kd iziid `l eil` aexw iziid ilel ik ,z"k zxcd z`n wegx izeid -

Final Copy of Dissertation

The Talmudic Zohar: Rabbinic Interdisciplinarity in Midrash ha-Ne’lam by Joseph Dov Rosen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, Chair Professor Deena Aranoff Professor Niklaus Largier Summer 2017 © Joseph Dov Rosen All Rights Reserved, 2017 Abstract The Talmudic Zohar: Rabbinic Interdisciplinarity in Midrash ha-Ne’lam By Joseph Dov Rosen Joint Doctor of Philosophy in Jewish Studies with the Graduate Theological Union University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, Chair This study uncovers the heretofore ignored prominence of talmudic features in Midrash ha-Ne’lam on Genesis, the earliest stratum of the zoharic corpus. It demonstrates that Midrash ha-Ne’lam, more often thought of as a mystical midrash, incorporates both rhetorical components from the Babylonian Talmud and practices of cognitive creativity from the medieval discipline of talmudic study into its esoteric midrash. By mapping these intersections of Midrash, Talmud, and Esotericism, this dissertation introduces a new framework for studying rabbinic interdisciplinarity—the ways that different rabbinic disciplines impact and transform each other. The first half of this dissertation examines medieval and modern attempts to connect or disconnect the disciplines of talmudic study and Jewish esotericism. Spanning from Maimonides’ reliance on Islamic models of Aristotelian dialectic to conjoin Pardes (Jewish esotericism) and talmudic logic, to Gershom Scholem’s juvenile fascination with the Babylonian Talmud, to contemporary endeavours to remedy the disciplinary schisms generated by Scholem’s founding models of Kabbalah (as a form of Judaism that is in tension with “rabbinic Judaism”), these two chapters tell a series of overlapping histories of Jewish inter/disciplinary projects. -

Original Citation: Devine, Luke (2020) Active/Passive, 'Diminished

Original citation: Devine, Luke (2020) Active/Passive, ‘Diminished’/‘Beautiful’, ‘Light’ from Above and Below: Rereading Shekhinah’s Sexual Desire in Zohar al Shir ha-Shirim (Song of Songs). Feminist Theology, 28 (3). pp. 297-315. ISSN Print: 0966-7350 Online: 1745 5189 DOI: 10.1177%2F0966735020906946 Permanent WRaP URL: https://eprints.worc.ac.uk/id/eprint/8418 Copyright and reuse: The Worcester Research and Publications (WRaP) makes this work available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRaP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published online by SAGE Publications in Feminist Theology for on 5 May 2020, available online: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0966735020906946 Copyright © 2020 by Feminist Theology and SAGE Publications. A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or, version of record, if you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the ‘permanent WRaP URL’ above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. -

Elements of Jewish Meditation

ELEMENTS OF JEWISH MEDITATION Introduction Jewish meditation is an ancient tradition that elevates Jewish thought, inspires Jewish practice, and deepens Jewish prayer. In its initial stages, Jewish meditation is a way to become more focused and aware. It enables the meditator to free the mind of all judgments, fears, doubts, and limiting ideas so that the voice of the soul is heard. With practice, the experience can be transformational, opening us to experience the Divine Presence during prayer, helping us discover deeper meaning in our lives, and connecting us spiritually to Jewish tradition. Jewish meditation can ultimately lead us to understand the true essence of Y-H-V-H through the practice of deeds of loving kindness and joyful compassion. Through meditation we can become attentive to the Divine imprint on our lives. I hope that Jewish meditation will become your practice for the rest of your life. It takes time to develop and refine a meditation practice. In this process it is useful to have a spiritual partner with whom you can explore the wondrous moments and the difficult ones. It is also important to keep a journal, where you write your thoughts down after each meditation and share them with your spiritual partner. Over the years Jewish meditation can lead to great spiritual transformation. What is Jewish Meditation? Jewish meditation is based in Jewish mysticism, a tradition present throughout Jewish history with strong ties to traditional Judaism. Jewish mysticism seeks to answers basic questions of life, such as the nature of God, the meaning of creation, and the existence of good and evil. -

Download (4MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Role of The Intellect In The Medieval Jewish and Islamic Mystical Traditions: A Comparative Study Between R Abulafia and Shaykh Suhrawardi By MARLINE SHAHEEN A Special Study presented as part of the requirement for the degree of Master of Theology University of Glasgow March 2000 ProQuest Number: 10390791 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10390791 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLO. -

Compassion for All Creatures

Compassion for all Creatures By Rabbi David Sears "God is good to all, and His mercy is upon all His works" (Psalms 145:9). This verse is the touchstone of the rabbinic attitude toward animal welfare, appearing in a number of contexts in Torah literature. The Torah espouses an ethic of compassion for all creatures, and affirms the sacredness of life. These values are reflected by the laws prohibiting tza’ar baalei chaim (cruelty to animals) and obligations for humans to treat animals with care. At first glance, the relevance of the above verse may seem somewhat obscure. It speaks of God, not man. However, a basic rule of Jewish ethics is the emulation of God's ways. In the words of the Talmudic sages: "Just as He clothes the naked, so shall you clothe the naked. Just as He is merciful, so shall you be merciful..." i Therefore, compassion for all creatures, including animals, is not only God's business; it is a virtue that we, too, must emulate. Moreover, rabbinic tradition asserts that God's mercy supersedes all other Divine attributes. Thus, compassion must not be reckoned as one good trait among others; rather, it is central to our entire approach to life. Benevolence entails action. Beyond the subjective factor of moral sentiment, Judaism 1) mandates kindness toward animals in halakhah (religious law), 2) prohibits their abuse, 3) praises their good traits, and 4) obligates their owners concerning their well-being. In this article, we consider our responsibilities to animals as creatures of God, deserving of compassion and respect.