Download (4MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 'Like Iron to a Magnet': Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence David Sclar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/380 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence By David Sclar A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 David Sclar All Rights Reserved This Manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Prof. Jane S. Gerber _______________ ____________________________________ Date Chair of the Examining Committee Prof. Helena Rosenblatt _______________ ____________________________________ Date Executive Officer Prof. Francesca Bregoli _______________________________________ Prof. Elisheva Carlebach ________________________________________ Prof. Robert Seltzer ________________________________________ Prof. David Sorkin ________________________________________ Supervisory Committee iii Abstract “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence by David Sclar Advisor: Prof. Jane S. Gerber This dissertation is a biographical study of Moses Hayim Luzzatto (1707–1746 or 1747). It presents the social and religious context in which Luzzatto was variously celebrated as the leader of a kabbalistic-messianic confraternity in Padua, condemned as a deviant threat by rabbis in Venice and central and eastern Europe, and accepted by the Portuguese Jewish community after relocating to Amsterdam. -

El Infinito Y El Lenguaje En La Kabbalah Judía: Un Enfoque Matemático, Lingüístico Y Filosófico

El Infinito y el Lenguaje en la Kabbalah judía: un enfoque matemático, lingüístico y filosófico Mario Javier Saban Cuño DEPARTAMENTO DE MATEMÁTICA APLICADA ESCUELA POLITÉCNICA SUPERIOR EL INFINITO Y EL LENGUAJE EN LA KABBALAH JUDÍA: UN ENFOQUE MATEMÁTICO, LINGÜÍSTICO Y FILOSÓFICO Mario Javier Sabán Cuño Tesis presentada para aspirar al grado de DOCTOR POR LA UNIVERSIDAD DE ALICANTE Métodos Matemáticos y Modelización en Ciencias e Ingeniería DOCTORADO EN MATEMÁTICA Dirigida por: DR. JOSUÉ NESCOLARDE SELVA Agradecimientos Siempre temo olvidarme de alguna persona entre los agradecimientos. Uno no llega nunca solo a obtener una sexta tesis doctoral. Es verdad que medita en la soledad los asuntos fundamentales del universo, pero la gran cantidad de familia y amigos que me han acompañado en estos últimos años son los co-creadores de este trabajo de investigación sobre el Infinito. En primer lugar a mi esposa Jacqueline Claudia Freund quien decidió en el año 2002 acompañarme a Barcelona dejando su vida en la Argentina para crear la hermosa familia que tenemos hoy. Ya mis dos hermosos niños, a Max David Saban Freund y a Lucas Eli Saban Freund para que logren crecer y ser felices en cualquier trabajo que emprendan en sus vidas y que puedan vislumbrar un mundo mejor. Quiero agradecer a mi padre David Saban, quien desde la lejanía geográfica de la Argentina me ha estimulado siempre a crecer a pesar de las dificultades de la vida. De él he aprendido dos de las grandes virtudes que creo poseer, la voluntad y el esfuerzo. Gracias papá. Esta tesis doctoral en Matemática Aplicada tiene una inmensa deuda con el Dr. -

Adas Israel Congregation June 2017 / Sivan–Tammuz 5777 Chronicle

Adas Israel Congregation June 2017 / Sivan–Tammuz 5777 Chronicle Join us for our annual cantorial concert featuring the Argen-Cantors Chronicle • May 2017 • 1 The Chronicle Is Supported in Part by the Ethel and Nat Popick Endowment Fund clergycorner From the President By Debby Joseph Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt In my early years of learning meditation I studied with Rabbi David Zeller (z”l), at Yakar, a wonderful synagogue in the heart of Jerusalem. I would go to his classes once a week and listen with strong intention to try to understand the practice of meditation, a practice that was changing my everyday life. During the past two years, when people Rabbi Zeller would talk often about the concept of devekut (attachment to learned that I was president of Adas Israel God) that the Hasidic masters had brought alive from teachings in the Zohar: Congregation, they inevitably cracked a “If you are already full, there is no room for God. Empty yourself like a vessel.” joke about feeling sorry for me. Never has I would try my hardest to understand what this meant, but I could not grasp that sentiment been further from the truth. I how to embody this concept, how to make it true to my own experience. have relished serving in this role. I have met How do you empty yourself? What does that feel like? many people, shared many experiences, For many years, in my own spiritual practice, I committed myself to learning and the feelings that permeated all that has meditation, sitting for 5, 10, 20, 30 minutes in silent meditation several times happened during my tenure make up one of a week. -

The Exalted Rebbe הצדיק הנשגב

THE EXALTED REBBE הצדיק הנשגב YESHUA IN LIGHT OF THE CHASSIDIC CONCEPTS OF DEVEKUT AND TZADDIKISM הקדמה לרעיון הדבקות בחסידות ויחסו למשיחיות ישוע THE EXALTED REBBE AN INTRODUCTION TO THE CONCEPT OF DEVEKUT AND TZADDIKISM IN CHASIDIC THOUGHT TOBY JANICKI Jewish critics of Messianic Judaism and the New Testament will often raise the argument that the Hebrew Scriptures do not set a precedent for the concept of an intercessor who stands between God and man. In other words, the idea that we need Messiah Yeshua to be the one to lead us to the Father and intercede on our behalf is not biblical. These critics state that we can approach God on our own faith and merit with no need for anyone to be a go-between. In their minds such an idea is idolatrous and completely foreign to Judaism. However, the talmudic sages of Israel developed the idea of the need for an intercessor in the con- cept of the tzaddik (“righteous one”). They, along with the later Chasidic movement, found proof for the need for an intermediary in the Torah and the rest of the Scriptures. By examining the tzaddik within Judaism we can not only defend our faith in the Master but we can also better understand His role from a Torah perspective. THE TZADDIK A true .(צדק ,is derived from the Hebrew word for “righteousness” (tzedek (צדיק) The word tzaddik tzaddik is a sinless person. Tzaddik has the sense of “one whose conduct is found to be beyond re- proach by the divine Judge.”1 According to the New Testament, there is no such person, “for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God,”2 the only exception being Yeshua of Nazareth, who was “tempted in all things as we are, yet without sin.”3 From apostolic reckoning and the perspective of Messianic faith, Yeshua is the only true tzaddik. -

The Archetype of the Tzaddiq in Hasidic Tradition

THE ARCHETYPE OF THE TZADDIQ IN HASIDIC TRADITION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA IN CONJUNCTION wlTH THE DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY YA'QUB IBN YUSUF August4, 1992 National Library B¡bliothèque nat¡onale E*E du Canada Acquisitions and D¡rection des acquisilions et B¡bliographic Services Branch des services bibliograPhiques 395 Wellinolon Slreêl 395, rue Wellington Oflawa. Oñlario Ottawa (Ontario) KlA ON4 K1A ON4 foùt t¡te vat¡e ¡élëte^ce Ou l¡te Nate élëtenæ The author has granted an L'auteur a accordé une licence irrevocable non-exclusive licence irrévocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of permettant à la Bibliothèque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationale du Canada de distribute or sell cop¡es of reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa thèse in any form or format, making de quelque manière et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette thèse à la disposition des personnes intéressées. The author retains ownership of L'auteur conserve la propriété du the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qui protège sa Neither the thesis nor substantial thèse. Ni la thèse ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiels de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent être imprimés ou his/her permission. autrement reproduits sans son autorisation, ïsBN ø-315-7796Ø-S -

Final Copy of Dissertation

The Talmudic Zohar: Rabbinic Interdisciplinarity in Midrash ha-Ne’lam by Joseph Dov Rosen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, Chair Professor Deena Aranoff Professor Niklaus Largier Summer 2017 © Joseph Dov Rosen All Rights Reserved, 2017 Abstract The Talmudic Zohar: Rabbinic Interdisciplinarity in Midrash ha-Ne’lam By Joseph Dov Rosen Joint Doctor of Philosophy in Jewish Studies with the Graduate Theological Union University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, Chair This study uncovers the heretofore ignored prominence of talmudic features in Midrash ha-Ne’lam on Genesis, the earliest stratum of the zoharic corpus. It demonstrates that Midrash ha-Ne’lam, more often thought of as a mystical midrash, incorporates both rhetorical components from the Babylonian Talmud and practices of cognitive creativity from the medieval discipline of talmudic study into its esoteric midrash. By mapping these intersections of Midrash, Talmud, and Esotericism, this dissertation introduces a new framework for studying rabbinic interdisciplinarity—the ways that different rabbinic disciplines impact and transform each other. The first half of this dissertation examines medieval and modern attempts to connect or disconnect the disciplines of talmudic study and Jewish esotericism. Spanning from Maimonides’ reliance on Islamic models of Aristotelian dialectic to conjoin Pardes (Jewish esotericism) and talmudic logic, to Gershom Scholem’s juvenile fascination with the Babylonian Talmud, to contemporary endeavours to remedy the disciplinary schisms generated by Scholem’s founding models of Kabbalah (as a form of Judaism that is in tension with “rabbinic Judaism”), these two chapters tell a series of overlapping histories of Jewish inter/disciplinary projects. -

Original Citation: Devine, Luke (2020) Active/Passive, 'Diminished

Original citation: Devine, Luke (2020) Active/Passive, ‘Diminished’/‘Beautiful’, ‘Light’ from Above and Below: Rereading Shekhinah’s Sexual Desire in Zohar al Shir ha-Shirim (Song of Songs). Feminist Theology, 28 (3). pp. 297-315. ISSN Print: 0966-7350 Online: 1745 5189 DOI: 10.1177%2F0966735020906946 Permanent WRaP URL: https://eprints.worc.ac.uk/id/eprint/8418 Copyright and reuse: The Worcester Research and Publications (WRaP) makes this work available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRaP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published online by SAGE Publications in Feminist Theology for on 5 May 2020, available online: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0966735020906946 Copyright © 2020 by Feminist Theology and SAGE Publications. A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or, version of record, if you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the ‘permanent WRaP URL’ above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. -

Elements of Jewish Meditation

ELEMENTS OF JEWISH MEDITATION Introduction Jewish meditation is an ancient tradition that elevates Jewish thought, inspires Jewish practice, and deepens Jewish prayer. In its initial stages, Jewish meditation is a way to become more focused and aware. It enables the meditator to free the mind of all judgments, fears, doubts, and limiting ideas so that the voice of the soul is heard. With practice, the experience can be transformational, opening us to experience the Divine Presence during prayer, helping us discover deeper meaning in our lives, and connecting us spiritually to Jewish tradition. Jewish meditation can ultimately lead us to understand the true essence of Y-H-V-H through the practice of deeds of loving kindness and joyful compassion. Through meditation we can become attentive to the Divine imprint on our lives. I hope that Jewish meditation will become your practice for the rest of your life. It takes time to develop and refine a meditation practice. In this process it is useful to have a spiritual partner with whom you can explore the wondrous moments and the difficult ones. It is also important to keep a journal, where you write your thoughts down after each meditation and share them with your spiritual partner. Over the years Jewish meditation can lead to great spiritual transformation. What is Jewish Meditation? Jewish meditation is based in Jewish mysticism, a tradition present throughout Jewish history with strong ties to traditional Judaism. Jewish mysticism seeks to answers basic questions of life, such as the nature of God, the meaning of creation, and the existence of good and evil. -

Luzzatto's Derech Hashem

Luzzatto’s Derech Hashem: Understanding the Way of God Shayna Rogozinsky, Jewish Studies Department, McGill University; Montreal August 2010 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Masters in Arts in Jewish Studies © Shayna Rogozinsky, 2010 1 Table of Contents: Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Luzzatto’s Derech Hashem: Understanding the Way of God 5 Introduction 5 On the Introduction to Derech Hashem 14 Fundamentals 19 Prophecy 31 On the Shema 48 Conclusion 52 Bibliography 54 2 Abstract: The aim of this paper is to introduce the reader to Moshe Chaim Luzzatto’s Derech Hashem and Luzzatto’s thought process. It begins with an analysis of the introduction to the work and then examines three major themes: Fundamentals, Prophecy, and the importance of the Shema prayer. Where applicable, comparisons will be made to other Jewish thinkers. Themes will be explained within the Kabbalistic framework that influenced Luzzatto’s work. By the end of the paper the reader should be able to grasp the key elements and reasons that inspired Luzzatto to write this book. Le but de ce document est de présenter le lecteur processus de Moshe Chaim Luzzatto de Derech Hashem et de Luzzatto à pensée. Il commence par une analyse de l'introduction au travail et puis examine trois thèmes importants : Principes fondamentaux, prophétie, et l'importance de la prière de Shema. Là où applicables, des comparaisons seront faites à d'autres penseurs juifs. Des thèmes seront expliqués dans le cadre de Kabbalistic que le travail de Luzzatto influencé. Vers la fin du papier le lecteur devrait pouvoir saisir les éléments clé et les raisons qui a inspiré Luzzatto écrire ce livre. -

Morgenstern Is a Senior Fellow at the Shalem Center in Jerusalem

Dispersion and the Longing for Zion, 1240-1840 rie orgenstern t has become increasingly accepted in recent years that Zionism is a I strictly modern nationalist movement, born just over a century ago, with the revolutionary aim of restoring Jewish sovereignty in the land of Israel. And indeed, Zionism was revolutionary in many ways: It rebelled against a tradition that in large part accepted the exile, and it attempted to bring to the Jewish people some of the nationalist ideas that were animat- ing European civilization in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centu- ries. But Zionist leaders always stressed that their movement had deep historical roots, and that it drew its vitality from forces that had shaped the Jewish consciousness over thousands of years. One such force was the Jewish faith in a national redemption—the belief that the Jews would ultimately return to the homeland from which they had been uprooted. This tension, between the modern and the traditional aspects of Zion- ism, has given rise to a contentious debate among scholars in Israel and elsewhere over the question of how the Zionist movement should be described. Was it basically a modern phenomenon, an imitation of the winter 5762 / 2002 • 71 other nationalist movements of nineteenth-century Europe? If so, then its continuous reference to the traditional roots of Jewish nationalism was in reality a kind of facade, a bid to create an “imaginary community” by selling a revisionist collective memory as if it had been part of the Jewish historical consciousness all along. Or is it possible to accept the claim of the early Zionists, that at the heart of their movement stood far more ancient hopes—and that what ultimately drove the most remarkable na- tional revival of modernity was an age-old messianic dream? For many years, it was the latter belief that prevailed among historians of Zionism. -

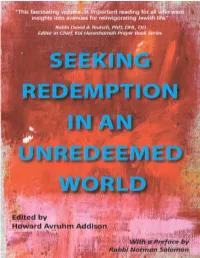

Seeking-Redemption-In-An-Unredeemed-World.Pdf

Praise for this book _________________________ The late Pope John Paul II once referred to the Jewish people as “our elder brothers in the faith of Abraham.” This insightful, probing, and very creative collection of essays on Jewish spirituality, edited by Rabbi Howard Addison, examines the many nuances of the Jewish understanding of redemption from a variety of perspectives and, in doing so, offers a fundamental backdrop against which Catholics and other Christians can examine their own understanding of the concept. For this reason, it is an invaluable tool for deepening our understanding of the roots our Christian heritage, challenging it, enriching it, and transforming it, so that we may enter into dialogue with our Jewish sisters and brothers and, indeed, with all who look to Abraham as their father in faith. Dennis J. Billy, C.Ss.R, ThD, STD, DMin John Cardinal Krol Chair of Moral Theology (2008-16) St. Charles Borromeo Seminary Author, Conscience and Prayer: The Spirit of Catholic Moral Theology Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, the founder of Judaism's Reconstructionist movement, taught that divine redemption is manifest in the human commitment to creativity and our efforts to achieve freedom. That understanding of salvation is exemplified in this fascinating volume. It explores spiritual direction, dance, art, liturgical innovation and social activism as practices for twenty-first- century spiritual renewal. In turn it connects them to Process Theology, beliefs in reincarnation and liberation theology in thought- provoking ways. It is important reading, especially for all who want insights into avenues for reinvigorating Jewish life. Rabbi David A. Teutsch, PhD, DHL, DD Wiener Professor Emeritus, Reconstructionist Rabbinical College Editor in Chief, Kol Haneshamah Prayer Book Series Seeking Redemption in an Unredeemed World offers fresh and diverse Jewish perspectives on the concept of redemption in Jewish life. -

Devekut & Yirat Shamayim

KosherTorah.com Parashat B’huko’tai Devekut & Yirat Shamayim, The Solution to the Problem By HaRav Ariel Bar Tzadok Copyright © 2000 by Ariel Bar Tzadok. All rights reserved. Rather than address any one pasuk (verse) in this parasha (Torah Portion), I felt drawn to address the entire issue of blessing and curse. It is no secret that the curses listed in this week’s parasha have all come true upon the Jewish people, often many times over. Whether Jews have been religious or irreligious, pogroms and holocausts have followed us throughout the centuries. There is obviously something very wrong here. HaShem does not send punishments upon us simply because He wants to. No, we are punished because we are not receiving the Divine message. And what message is that? Read on. One of the concepts that I find hard for people today to understand is that HaShem is the Living G-d of Israel and that we must each cultivate a personal experiential relationship with out Creator. Even within the religious community where Torah study and the observance of mitzvot are paramount, many still have a hard time accepting the idea that they can and that they must talk directly with HaShem and be aware of His Presence and Will constantly. Barukh HaShem that today we have so many yeshivot. More people than ever are studying Torah, more people are becoming Ba’alei Teshuva (returning to religion). Indeed, today we find that there are more properly prepared people who are studying kosher Sitrei Torah (the secrets of Torah). Yet, with all this expansiveness of learning, there still seems to be one mitzvah that we severely lack.