Conversations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Difference Between Blessing (Bracha) and Prayer (Tefilah)

1 The Difference between Blessing (bracha) and Prayer (tefilah) What is a Bracha? On the most basic level, a bracha is a means of recognizing the good that God has given to us. As the Talmud2 states, the entire world belongs to God, who created everything, and partaking in His creation without consent would be tantamount to stealing. When we acknowledge that our food comes from God – i.e. we say a bracha – God grants us permission to partake in the world's pleasures. This fulfills the purpose of existence: To recognize God and come close to Him. Once we have been satiated, we again bless God, expressing our appreciation for what He has given us.3 So, first and foremost, a bracha is a "please" and a "thank you" to the Creator for the sustenance and pleasure He has bestowed upon us. The Midrash4 relates that Abraham's tent was pitched in the middle of an intercity highway, and open on all four sides so that any traveler was welcome to a royal feast. Inevitably, at the end of the meal, the grateful guests would want to thank Abraham. "It's not me who you should be thanking," Abraham replied. "God provides our food and sustains us moment by moment. To Him we should give thanks!" Those who balked at the idea of thanking God were offered an alternative: Pay full price for the meal. Considering the high price for a fabulous meal in the desert, Abraham succeeded in inspiring even the skeptics to "give God a try." Source of All Blessing Yet the essence of a bracha goes beyond mere manners. -

Sermon: How As a Christian Should I Respond? (Jen Goode 03‐04‐2018)

Page 1 – Sermon: How as a Christian should I respond? (Jen Goode 03‐04‐2018) (Exodus 20:1‐17; Psalm 19; John 2:13‐22) Let us pray: Holy One, I pray that the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart will be acceptable in your sight, my rock and my redeemer. Amen. On January 13 of this year, I posted on my Facebook page a letter I had seen to a company called Scholastic. I’m not sure if you all know this company, but Scholastic encourages school‐aged children to purchase books through monthly flyers that are sent home in backpacks. This is the letter Jaime Brusehoff wrote: “Dear Scholastic: I’ve heard you’ve been targeted … for offering and celebrating books that are LGBTQ‐inclusive. I’m sorry they’re targeting you with their ignorance and miseducation. As the mom of a transgender child, I want to say thank you. What you are doing matters. Your books make a difference. Representation matters, and when my transgender daughter reads a book that features a transgender character, she feels seen, affirmed, and valued. She thrives knowing that her peers are reading books about kids like her too. When she meets a new friend who doesn’t quite understand what it means to be transgender, do you know what she does? She hands them a book. I regularly do trainings for educators and other professionals who work with youth, and when I come with my stack of children’s books that celebrate gender creative and transgender kids, they are so happy and relieved. -

Women As Shelihot Tzibur for Hallel on Rosh Hodesh

MilinHavivinEng1 7/5/05 11:48 AM Page 84 William Friedman is a first-year student at YCT Rabbinical School. WOMEN AS SHELIHOT TZIBBUR FOR HALLEL ON ROSH HODESH* William Friedman I. INTRODUCTION Contemporary sifrei halakhah which address the issue of women’s obligation to recite hallel on Rosh Hodesh are unanimous—they are entirely exempt (peturot).1 The basis given by most2 of them is that hallel is a positive time-bound com- mandment (mitzvat aseh shehazman gramah), based on Sukkah 3:10 and Tosafot.3 That Mishnah states: “One for whom a slave, a woman, or a child read it (hallel)—he must answer after them what they said, and a curse will come to him.”4 Tosafot comment: “The inference (mashma) here is that a woman is exempt from the hallel of Sukkot, and likewise that of Shavuot, and the reason is that it is a positive time-bound commandment.” Rosh Hodesh, however, is not mentioned in the list of exemptions. * The scope of this article is limited to the technical halakhic issues involved in the spe- cific area of women’s obligation to recite hallel on Rosh Hodesh as it compares to that of men. Issues such as changing minhag, kol isha, areivut, and the proper role of women in Jewish life are beyond that scope. 1 R. Imanu’el ben Hayim Bashari, Bat Melekh (Bnei Brak, 1999), 28:1 (82); Eliyakim Getsel Ellinson, haIsha vehaMitzvot Sefer Rishon—Bein haIsha leYotzrah (Jerusalem, 1977), 113, 10:2 (116-117); R. David ben Avraham Dov Auerbakh, Halikhot Beitah (Jerusalem, 1982), 8:6-7 (58-59); R. -

Maimonides on the First Commandment: Belief In

Special for Shavuoth 5768 Is Belief in God a Miztvah? Maimonides on the First Commandment Rabbi Assaf Bednarsh The first of the Ten Commandments, which we will read with much fanfare on Shavuot morning, is “Anochi Hashem Elokecha” – I am the Lord your God. Or is it? The Torah never actually refers to ten commandments, but to “Aseret HaDibrot”, ten statements, that God uttered to the Jewish people at Sinai. While the importance of these ten statements has never been questioned, the question of whether they in fact constitute commandments is quite controversial, specifically with regard to the first of these statements. Rambam, in his Sefer HaMitzvot, counts belief in God as the very first mitzvah, and cites “Anochi Hashem Elokecha” as the Biblical source for the commandment of faith. Ramban, however, in his glosses to Sefer HaMitzvot, points out that the passuk is not phrased as a commandment – “Believe in the Lord your God”, but rather as a statement of fact – “I am the Lord your God.” Therefore, the earlier mitzvah compendium Halachot Gedolot did not count the first of the ten statements as one of the 613 commandments, viewing it rather as a statement of theological fact. Of course, Halachot Gedolot does not deny that a good Jew must believe in God, but he understands that this requirement is too basic to be counted as a mitzvah. Faith is the pillar which supports all the 613 mitzvot of the Torah, and thus is not considered one of them. Rav Soloveitchik once summarized this disagreement using halachic terminology –Rambam considers faith as a mitzvah, but Halachot Gedolot considers it a “hechsher mitzvah”, a necessary precondition of the mitzvot. -

Etzionupdate from Yeshivat Har Etzion

בסד Summer 5777/2017 etzionUPDATE from Yeshivat Har Etzion Etzion Foundation Dinner 2017 On Wednesday March 29, hundreds of when Racheli delivered words of thanks The dinner culminated with dancing, friends gathered for the annual Etzion and chizuk. All the honorees appeared in bringing together all the members of the Foundation Dinner. The Foundation was a video presentation that also featured Gush community – Ramim and alumni, proud to present the Alumnus of the Year Roshei Yeshiva, Ramim, peers, children parents and children all rejoicing arm in award to Rabbi Jeffrey Kobrin ’92PC and and talmidim. The videos can be viewed at arm. Yair Hindin ‘98 commented, “It‘s this Michelle Greenberg-Kobrin. Simcha and http://haretzion.org/2017-honorees sense of community that always pulses Barbara Hochman, parents of Ayelet ’11MO through the Grand Hyatt during the Gush Rosh Yeshiva Rav Mosheh Lichtenstein and Ariel ’13, were honored with the dinner, this sense of the common bonds we spoke nostalgically and passionately of Parents of the Year award. all share, that keeps me coming back year the early days of his family’s aliyah and after year.” The Dor l’Dor Award was given to the state of the Yeshiva upon their arrival. Rav Danny Rhein his daughter, Describing the present, he noted the near Before the dinner, a reception was held Racheli (Rhein) Schmell ’07MO, whose impossibility of imagining not only the honoring the alumni of ’96 and ’97 on their combined warmth exponentially impacts current success of Gush but also the ever- 20th anniversary. In honor of the occasion, the tone and flavor of both Yeshivat Har growing presence that Migdal Oz has on the students from those years formed Etzion and Migdal Oz. -

Sanhedrin 053.Pub

ט"ז אלול תשעז“ Thursday, Sep 7 2017 ן נ“ג סנהדרי OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT to apply stoning to other cases גזירה שוה Strangulation for adultery (cont.) The source of the (1 ואלא מכה אביו ואמו קא קשיא ליה, למיתי ולמיגמר מאוב וידעוני R’ Yoshiya’s opinion in the Beraisa is unsuccessfully וכו ‘ ליגמרו מאשת איש, דאי אתה רשאי למושכה להחמיר עליה וכו‘ .challenged at the bottom of 53b lists אלו הן הנסקלין Stoning T he Mishnah of (2 The Mishnah later derives other cases of stoning from a many cases which are punished with stoning. R’ Zeira notes gezeirah shavah from Ov and Yidoni. R’ Zeira questions that the Torah only specifies stoning explicitly in a handful גזירה שוה of cases, while the other cases are learned using a דמיהם בם or the words מות יומתו whether it is the words Rashi states that the cases where we find . אוב וידעוני that are used to make that gezeirah shavah. from -stoning explicitly are idolatry, adultery of a betrothed maid . דמיהם בם Abaye answers that it is from the words Abaye’s explanation is defended. en, violating the Shabbos, sorcery and cursing the name of R’ Acha of Difti questions what would have bothered R’ God. Aruch LaNer points out that there are three addition- Zeira had the gezeirah shavah been made from the words al cases where we find stoning mentioned outright (i.e., sub- ,mitting one’s children to Molech, inciting others to idolatry . מות יומתו In any case, there .( בן סורר ומורה—After R’ Acha of Difti suggests and rejects a number of and an recalcitrant son גזירה possible explanations Ravina explains what was troubling R’ are several cases of stoning which are derived from the R’ Zeira asks Abaye to identify the source from which . -

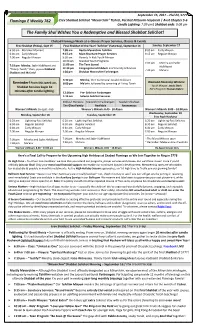

The Family Shul Wishes You a Redemptive and Blessed Shabbat Selichot!

September 15, 2017 – Elul 24, 5777 Flamingo E Weekly 762 Erev Shabbat Selichot “Mevarchim” Tishrei, Parshat Nitzavim-Vayelech | Avot Chapter 5-6 Candle Lighting: 7:09 pm| Shabbat ends: 8:08 pm The Family Shul Wishes You a Redemptive and Blessed Shabbat Selichot! Chabad Flamingo Week-at-a-Glance: Prayer Services, Classes & Events Erev Shabbat (Friday), Sept 15 Final Shabbat-of-the-Year! “Selichot” (Saturday), September 16 Sunday, September 17 6:30 am Ma’amer Moment 7:00 am Recite Mevarchim Tehillim 8:00 am Early Minyan 6:40 am Early Minyan 9:15 am Main Shacharit Prayer Services 9:15 am Regular Minyan 7:00 am Regular Minyan 9:30 am Parents ’n Kids Youth Minyan 10:30 am Shabbat Youth Programs 7:00 pm Mincha and Sefer 11:00 am The Teen Scene! 7:19 pm Mincha, Sefer HaMitzvot and HaMitzvot 12:30 pm Congregational Kiddush and Friendly Schmooze “Timely Torah;” then, joyous Kabbalat 7:30 pm Ma’ariv 1:30 pm Shabbat Mevarchim Farbrengen Shabbat and Ma’ariv! 6:30 pm Mincha, then Communal Seudah Shlisheet Reminder! From this week on, 8:00 pm Ma’ariv, followed by screening of Living Torah Diamond Davening Winners: Shabbat Services begin 10 Youth Minyan: Jacob Stark Kid’s Program: Hudson Kobric minutes after candle lighting. 12:00am Pre- Selicho t Farbrengen 1:15 am Solemn Selichot Services Kiddush Honours: Mevarchim Farbrengen: Seudah Shlisheet The Glina Family Available Anonymous Women’s Mikvah: by appt. only Women’s Mikvah: 8:45 - 10:45pm Women’s Mikvah: 8:00 – 10:00 pm Wednesday, September 20 Monday, September 18 Tuesday, September 19 Erev Rosh -

Rosh Hashanah Jewish New Year

ROSH HASHANAH JEWISH NEW YEAR “The LORD spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to the Israelite people thus: In the seventh month, on the first day of the month, you shall observe complete rest, a sacred occasion commemorated with loud blasts. You shall not work at your occupations; and you shall bring an offering by fire to the LORD.” (Lev. 23:23-25) ROSH HASHANAH, the first day of the seventh month (the month of Tishri), is celebrated as “New Year’s Day”. On that day the Jewish people wish one another Shanah Tovah, Happy New Year. ש נ ָׁהָׁטוֹב ָׁה Rosh HaShanah, however, is more than a celebration of a new calendar year; it is a new year for Sabbatical years, a new year for Jubilee years, and a new year for tithing vegetables. Rosh HaShanah is the BIRTHDAY OF THE WORLD, the anniversary of creation—a fourfold event… DAY OF SHOFAR BLOWING NEW YEAR’S DAY One of the special features of the Rosh HaShanah prayer [ רֹאשָׁהַש נה] Rosh HaShanah THE DAY OF SHOFAR BLOWING services is the sounding of the shofar (the ram’s horn). The shofar, first heard at Sinai is [זִכְּ רוֹןָׁתְּ רּועה|יוֹםָׁתְּ רּועה] Zikaron Teruah|Yom Teruah THE DAY OF JUDGMENT heard again as a sign of the .coming redemption [יוֹםָׁהַדִ ין] Yom HaDin THE DAY OF REMEMBRANCE THE DAY OF JUDGMENT It is believed that on Rosh [יוֹםָׁהַזִכְּ רוֹן] Yom HaZikaron HaShanah that the destiny of 1 all humankind is recorded in ‘the Book of Life’… “…On Rosh HaShanah it is written, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed, how many will leave this world and how many will be born into it, who will live and who will die.. -

Rav Yisroel Abuchatzeira, Baba Sali Zt”L

Issue (# 14) A Tzaddik, or righteous person makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. (Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach; Sefer Bereishis 7:1) Parshas Bo Kedushas Ha'Levi'im THE TEFILLIN OF THE MASTER OF THE WORLD You shall say it is a pesach offering to Hashem, who passed over the houses of the children of Israel... (Shemos 12:27) The holy Berditchever asks the following question in Kedushas Levi: Why is it that we call the yom tov that the Torah designated as “Chag HaMatzos,” the Festival of Unleavened Bread, by the name Pesach? Where does the Torah indicate that we might call this yom tov by the name Pesach? Any time the Torah mentions this yom tov, it is called “Chag HaMatzos.” He answered by explaining that it is written elsewhere, “Ani l’dodi v’dodi li — I am my Beloved’s and my Beloved is mine” (Shir HaShirim 6:3). This teaches that we relate the praises of HaKadosh Baruch Hu, and He in turn praises us. So, too, we don tefillin, which contain the praises of HaKadosh Baruch Hu, and HaKadosh Baruch Hu dons His “tefillin,” in which the praise of Klal Yisrael is written. This will help us understand what is written in the Tanna D’Vei Eliyahu [regarding the praises of Klal Yisrael]. The Midrash there says, “It is a mitzvah to speak the praises of Yisrael, and Hashem Yisbarach gets great nachas and pleasure from this praise.” It seems to me, says the Kedushas Levi, that for this reason it says that it is forbidden to break one’s concentration on one’s tefillin while wearing them, that it is a mitzvah for a man to continuously be occupied with the mitzvah of tefillin. -

TRANSGENDER JEWS and HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A

TRANSGENDER JEWS AND HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A. Sharzer MD This teshuvah was adopted by the CJLS on June 7, 2017, by a vote of 11 in favor, 8 abstaining. Members voting in favor: Rabbis Aaron Alexander, Pamela Barmash, Elliot Dorff, Susan Grossman, Reuven Hammer, Jan Kaufman, Gail Labovitz, Amy Levin, Daniel Nevins, Avram Reisner, and Iscah Waldman. Members abstaining: Rabbis Noah Bickart, Baruch Frydman- Kohl, Joshua Heller, David Hoffman, Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Jonathan Lubliner, Micah Peltz, and Paul Plotkin. שאלות 1. What are the appropriate rituals for conversion to Judaism of transgender individuals? 2. What are the appropriate rituals for solemnizing a marriage in which one or both parties are transgender? 3. How is the marriage of a transgender person (which was entered into before transition) to be dissolved (after transition). 4. Are there any requirements for continuing a marriage entered into before transition after one of the partners transitions? 5. Are hormonal therapy and gender confirming surgery permissible for people with gender dysphoria? 6. Are trans men permitted to become pregnant? 7. How must healthcare professionals interact with transgender people? 8. Who should prepare the body of a transgender person for burial? 9. Are preoperative2 trans men obligated for tohorat ha-mishpahah? 10. Are preoperative trans women obligated for brit milah? 11. At what point in the process of transition is the person recognized as the new gender? 12. Is a ritual necessary to effect the transition of a trans person? The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halkhhah for the Conservative movement. -

Designing the Talmud: the Origins of the Printed Talmudic Page

Marvin J. Heller The author has published Printing the Talmud: A History of the Earliest Printed Editions of the Talmud. DESIGNING THE TALMUD: THE ORIGINS OF THE PRINTED TALMUDIC PAGE non-biblical Jewish work,i Its redaction was completed at the The Talmudbeginning is indisputablyof the fifth century the most and the important most important and influential commen- taries were written in the middle ages. Studied without interruption for a milennium and a half, it is surprising just how significant an eftèct the invention of printing, a relatively late occurrence, had upon the Talmud. The ramifications of Gutenberg's invention are well known. One of the consequences not foreseen by the early practitioners of the "Holy Work" and commonly associated with the Industrial Revolution, was the introduction of standardization. The spread of printing meant that distinct scribal styles became generic fonts, erratic spellngs became uni- form and sequential numbering of pages became standard. The first printed books (incunabula) were typeset copies of manu- scripts, lacking pagination and often not uniform. As a result, incunabu- la share many characteristics with manuscripts, such as leaving a blank space for the first letter or word to be embellshed with an ornamental woodcut, a colophon at the end of the work rather than a title page, and the use of signatures but no pagination.2 The Gutenberg Bibles, for example, were printed with blank spaces to be completed by calligra- phers, accounting for the varying appearance of the surviving Bibles. Hebrew books, too, shared many features with manuscripts; A. M. Habermann writes that "Conats type-faces were cast after his own handwriting, . -

Wage Theft and Consumer Boycotts -למען נחדל מעשק ידינו

Wage Theft and Consumer Boycotts -למען נחדל מעשק ידינו Morris Panitz, Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies Introduction: The Consumer Boycott as a Resistance Strategy Consumer boycotts are a resistance strategy that draws heavily on the foundational principles of civil disobedience.1 An individual engaged in an act of civil disobedience “seeks not only to convey her disavowal and condemnation of a certain law or policy, but also to draw public attention to this particular issue and thereby to instigate a change in law or policy.”2 The public sphere serves as the ideal forum for civil disobedience for two reasons. First, the target of the direct action is forced to confront the issue under the scrutiny of the public eye, thereby raising the stakes for how the issue is dealt with. Ideally, the public will hold the target accountable for its response to the act of civil disobedience. Second, the calculation on the part of the target of whether or not to meet the demands of the protestors is partially determined by the following generated by the act of civil disobedience. Thus, the public sphere helps attract further support to instigate a change in law or policy. Consumer boycott campaigns are “where citizens act collectively and use their purchasing power to achieve economic, social or political objectives….Consumers can use their purchasing power as a kind of vote that is capable, among other things, of educating corporate 1 I am grateful to Rabbis Elliot Dorff and Aryeh Cohen for their thoughtful teaching and editorial remarks that shaped the development of this essay.