Blogging Rav Lichtenstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Etzionupdate from Yeshivat Har Etzion

בסד Summer 5777/2017 etzionUPDATE from Yeshivat Har Etzion Etzion Foundation Dinner 2017 On Wednesday March 29, hundreds of when Racheli delivered words of thanks The dinner culminated with dancing, friends gathered for the annual Etzion and chizuk. All the honorees appeared in bringing together all the members of the Foundation Dinner. The Foundation was a video presentation that also featured Gush community – Ramim and alumni, proud to present the Alumnus of the Year Roshei Yeshiva, Ramim, peers, children parents and children all rejoicing arm in award to Rabbi Jeffrey Kobrin ’92PC and and talmidim. The videos can be viewed at arm. Yair Hindin ‘98 commented, “It‘s this Michelle Greenberg-Kobrin. Simcha and http://haretzion.org/2017-honorees sense of community that always pulses Barbara Hochman, parents of Ayelet ’11MO through the Grand Hyatt during the Gush Rosh Yeshiva Rav Mosheh Lichtenstein and Ariel ’13, were honored with the dinner, this sense of the common bonds we spoke nostalgically and passionately of Parents of the Year award. all share, that keeps me coming back year the early days of his family’s aliyah and after year.” The Dor l’Dor Award was given to the state of the Yeshiva upon their arrival. Rav Danny Rhein his daughter, Describing the present, he noted the near Before the dinner, a reception was held Racheli (Rhein) Schmell ’07MO, whose impossibility of imagining not only the honoring the alumni of ’96 and ’97 on their combined warmth exponentially impacts current success of Gush but also the ever- 20th anniversary. In honor of the occasion, the tone and flavor of both Yeshivat Har growing presence that Migdal Oz has on the students from those years formed Etzion and Migdal Oz. -

Tevul Yom Chapter 1

Mishna - Mas. Tevul Yom Chapter 1 MISHNAH 1. IF ONE1 HAD COLLECTED DOUGH-OFFERING2 [PORTIONS] WITH THE INTENTION OF SEGREGATING THEM AFTERWARDS AGAIN, BUT IN THE MEANTIME THEY HAD BECOME STUCK TOGETHER,3 BETH SHAMMAI SAY: THEY SERVE AS CONNECTIVES4 IN THE CASE OF A TEBUL YOM. BUT BETH HILLEL SAY: THEY DO NOT SERVE AS CONNECTIVES. PIECES OF DOUGH5 THAT HAD BECOME STUCK TOGETHER, OR LOAVES5 THAT HAD BECOME JOINED, OR A BATTER-CAKE THAT HAD BEEN BAKED ON TOP OF ANOTHER BATTER-CAKE BEFORE IT COULD FORM A CRUST IN THE OVEN, OR IF THERE WAS FROTH6 ON THE WATER THAT WAS BUBBLING, OR THE FIRST SCUM7 THAT RISES WHEN BOILING GROATS OF BEANS, OR THE SCUM OF NEW WINE (R. JUDAH SAYS: ALSO THAT OF RICE) BETH SHAMMAI SAY: ALL SERVE AS CONNECTIVES IN THE CASE OF THE TEBUL YOM. BUT BETH HILLEL SAY: THEY DO NOT SERVE AS CONNECTIVES.8 THEY9 CONCUR, HOWEVER, [THAT THEY SERVE AS CONNECTIVES] IF THEY COME INTO CONTACT WITH OTHER KINDS OF UNCLEANNESS, WHETHER THEY BE OF MINOR10 OR MAJOR GRADES.11 MISHNAH 2. IF ONE HAD COLLECTED PIECES OF DOUGH-OFFERING NOT WITH THE INTENTION OF SEGREGATING THEM AFTERWARDS, OR A BATTER-CAKE THAT HAD BEEN BAKED ON ANOTHER AFTER A CRUST HAD FORMED IN THE OVEN,12 OR A FROTH HAD APPEARED IN THE WATER PRIOR TO ITS BUBBLING UP, OR THE SECOND SCUM THAT APPEARED IN THE BOILING OF GROATS OF BEANS, OR THE SCUM OF OLD WINE, OR THAT OF OIL OF ALL KINDS,13 OR OF LENTILS (R. -

Parashat Pinchas

1111u lil n11w1 Yeshivat Har Etzion - Israel Koschitzky VBM Parsha Digest, Year Ill, Parashat Pinchas 5781 Selected and Adapted by Rabbi Dov Karoll Quote from the Rosh Yeshiva To those who have, over the years, been privileged to hear Rav Amital, the day [Rosh Hashanah/Yom Kippur], the man an d the tefillot are all inextricably interwoven. The lilting cadences of his renditions remain a permanently haunting presence, pregnant with quiet vigor and laden with pervasive emotion. Who can forget the compressed humility of his \!JY)'.))'.) ')Yil '))il, or the plaintive lament of his rnJ7)'.) ')llil ill\!JY, its tragic sequence interrupted only for the gnawing, sobbing, query, of the survivor, asking, with the paytan and out of the profundity of his emunah, illJ\!J m illln 1r? "Is this Torah and its reward"? Or the tuneful optimism of the complex of l)~mm □ l'il, followed by the conclusion of NJ.7 N)'.)7\!J Nil' of kaddish? Or the reverential joy with which, figuratively holding a thousand mit'pallelim in his hand, he leads them, to the climactic resolution of keter? No one. What we, impelled by conscience and enriched by experience, can do is to strive to remember and to perpetuate; to harness our energies in order to assure that the world which nurtured Rav Am ital and which he then re-created, join the ranks of those which □ Ylm ')10' N7 □ l]Tl □ '"Tlil'il 7,n)'.) llJ.Y' N7. -Harav Aharon Lichtenstein zt"I, Rosh Hashanah message 5771 [shared to commemorate Harav Amital's 11th Yahrzeit, 27 Tammuz] Parashat Pinchas Is the Zeal of Pinchas to be Emulated? By Harav Yehuda Amital zt"I Based on: https:// etzion .org.il/ en/tanakh/torah/sefer-ba mid bar/ parashat-pincha s/ pinchas-zeal-pinchas-be-emu lated Pinchas son of Elazar son of Aharon, the kohen, turned back My anger from Bnei Yisrael, in his zeal for My sake among that I did not destroy Bnei Yisrael in My zeal. -

Wozner Review Preprint

Review for JEWISH LAW ANNUAL of: Shai Wozner Legal Thinking in the Lithuanian Yeshivot: The Heritage and Works of Rabbi Shimon Shkop. שקופחשיבה משפטית בישיבות ליטא: עיונים במשנתו של הרב שמעון .תשע"ו/Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 2016 Norman Solomon1 Half a century ago, in 1966, I completed my own PhD thesis on what I named “The Analytic School in Rabbinic Jurisprudence” (it was not published in full until 1993). There could be no more satisfying “jubilee gift” (though not intended as such) than to receive a review copy of Shai Wozner’s fine Hebrew thesis on the methodology of one of the pioneers of the school, R. Shimon Shkop. Wozner repeatedly remarks on the Analytic Movement as in some sense a reaction to Haskala; like other reactions, it selectively adopts language and concepts from its opponents. I coined the term “Counter Haskala” for this phenomenon, by analogy with “Counter Reformation,” but it has not caught on. Reaction to Haskala extends far beyond the limited sphere of the conceptual analysis of halakha; indeed, the whole trajectory of post- Enlightenment Orthodoxy can only be understood in this context. The challenge was not merely, or even primarily, intellectual. The social and educational measures for “improvement” of the Jews initiated under Czar Nicholas I (1825-55), who amongst other things formally abolished the Kahal in 1843, were supported by Maskilim, but were perceived by much of the traditional religious leadership as a threat to their own authority. If Jews became citizens of the states in which they lived, as they had done in England, France and some German states (and of course America), they would be subject to the jurisdiction of those states, and not to Torah law as administered by the rabbis. -

Mishnah 1: If Two Women Each Made a Qab1 and They Touched One Another, Even If They Are of the Same Kind They Are Exempt

'ΪΓ3Ί pD D*tM TIU; v>3>3 ID rip ΓΙ* IVJJ·) ΨΨ i^V Ο'ψί >ΓΙψ :N fl)VÖ (fol. 59c) .moa ύ>»ι Ν'^ψι n»n ρ« ΠΠΝ nwN>\y "irw ijppi .p-no? inis Mishnah 1: If two women each made a qab1 and they touched one another, even if they are of the same kind they are exempt. But if both belong to the same woman and are of the same kind they are obligated2, different kinds3 are exempt. 5 1 They separately made bread are obligated since 2 > /4. dough and now are baking it together 2 If the doughs touch or are on in the same oven. Separately, the the same baking sheet. doughs are exempt but both together 3 This is defined in Mishnah 4:2. ηψκ Drip ·)3ηί> -ION .'^Ό D>\M >ΓΙψ :N (fol. 59d) rmiN wy rii?po ΠΠΝ Π\ΙΪΝ on ni-papo ο?ηψ JTj?p)o nj>N ηηκ π^ν on .πηΝ ηψΝ? oriiN wy πίτ?^ ο>ψ3 >jw .o>\w >ri\y? Dip» TÖ D3V .ΓΐίΟίρρ ΠΓΐίΜ ΓΙψίν Ν1Π ΐ\ΥΪ) Π13ρ» iniN η'ψίν Nin·) wibb oip)? tö γρπ ddp n>ri>>o .vytob >Γΐψ πη ί»κ JTjapjo ii'p-! 'pi τπ?Ρ2 ηίηίρρ .nisin I^SN ">? ^»ψ ,D>\M 'Γΐψ3 piiN Vwy riiv>i Halakhah 1: "Two women who each made," etc. Rebbi Johanan said, usually for women, one does not mind, two do mind4. They gave to one woman who minds5 the status of two women, to two women who do not mind the status of one woman. -

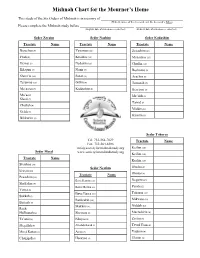

English Mishnah Chart

Mishnah Chart for the Mourner’s Home This study of the Six Orders of Mishnah is in memory of (Hebrew names of the deceased, and the deceased’s father) Please complete the Mishnah study before (English date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) (Hebrew date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) Seder Zeraim Seder Nashim Seder Kodashim Tractate Name Tractate Name Tractate Name Berachos (9) Yevamos (16) Zevachim (14) Peah (8) Kesubos (13) Menachos (13) Demai (7) Nedarim (11) Chullin (12) Kilayim (9) Nazir (9) Bechoros (9) Shevi’is (10) Sotah (9) Arachin (9) Terumos (11) Gittin (9) Temurah (7) Ma’asros (5) Kiddushin (4) Kereisos (6) Ma’aser Me’ilah (6) Sheni (5) Tamid (7) Challah (4) Middos (5) Orlah (3) Kinnim (3) Bikkurim (3) Seder Tohoros Tel: 732-364-7029 Tractate Name Fax: 732-364-8386 [email protected] Keilim (10) Seder Moed www.societyformishnahstudy.org Keilim (10) Tractate Name Keilim (10) Shabbos (24) Seder Nezikin Oholos (9) Eruvin (10) Tractate Name Oholos (9) Pesachim (10) Bava Kamma (10) Negaim (14) Shekalim (8) Bava Metzia (10) Parah (12) Yoma (8) Bava Basra (10) Tohoros (10) Sukkah (5) Sanhedrin (11) Mikvaos (10) Beitzah (5) Makkos (3) Niddah (10) Rosh HaShanah (4) Shevuos (8) Machshirin (6) Ta’anis (4) Eduyos (8) Zavim (5) Megillah (4) Avodah Zarah (5) Tevul Yom (4) Moed Kattan (3) Avos (5) Yadaim (4) Chagigah (3) Horayos (3) Uktzin (3) • Our Sages have said that Asher, son of the Patriarch Jacob sits at the opening to Gehinom (Purgatory), and saves [from entering therein] anyone on whose behalf Mishnah is being studied . -

CONGREGATION BETH AARON SHABBAT ANNOUNCEMENTS Parshat Tazria/ Hachodesh March 28-29, 2014 27Adar II 5774

CONGREGATION BETH AARON SHABBAT ANNOUNCEMENTS Parshat Tazria/ HaChodesh March 28-29, 2014 27Adar II 5774 SHABBAT TIMES This week’s announcements are sponsored by Friday, March 28: NORPAC Mission to Washington on Wednesday, April 30. Plag Mincha/Kabbalat Shabbat: 5:45 p.m. Register at www.norpac.net. Earliest Candles: 5:58 p.m. Latest Candles: 6:58 p.m. Mincha/Kabbalat Shabbat: 7:00 p.m. This week’s announcements are sponsored by Jack Rosenbaum, in honor of Rabbi Yitz Furst Shabbat, March 29: for his many, many years of serving as gabbai at the weekday 6:20/6:30 a.m. minyan. Hashkama Minyan: 7:30 a.m. Tefillah Shiur: 8:20 a.m. Main Minyan: 8:45 a.m. SCHEDULE FOR THE WEEK OF MARCH 30 Youth Minyan: 9:15 a.m. Sun Mon Tues Wed Thu Fri Sof Zman Kriat Shema: 9:55 a.m. 30 31 1 2 3 4 Early Mincha: 1:45 p.m. Daf Yomi: 5:30 p.m. Earliest Tallit 5:43 5:42 5:40 5:38 5:37 5:35 Women’s Learning: 5:30 p.m., at the Shacharit 6:30 MS 5:40 SH 5:35 SH 5:55 SH 5:40 SH 5:55 SH Greenberg home, 291 Schley Place, 7:15 MS 6:20 BM 6:10 BM 6:30 BM 6:20 BM 6:30 BM Pirkei Avot 8:00 MS 7:10 BM 7:05 BM 7:15 BM 7:10 BM 7:15 BM Mincha: 6:40 p.m., followed by Seudah 8:45 MS 8:00 BM 8:00 BM 8:00 BM 8:00 BM 8:00 BM Shlishit. -

Judges) “In All Your Gates” That They Are to Judge the People with Righteous Judgment

בייה PORTION DATE HEB DATE TORAH NEVIIM RENEWED Shoftim 18 Aug. 2018 7 Elul 5778 Deut. 16:18-21:9 Isa. 51:12-52:12 John 14:9-20 This week’s Torah portion starts with the qualification of shoftim (judges) “in all your gates” that they are to judge the people with righteous judgment. The Torah then describes how they are to judge against the accused. The Midrash questions the eligibility of judges. The immediate family of litigants are disqualified to judge as well as they are ineligible to testify as said, “The ahvot (fathers) shall not be put to death for the children, neither shall the children be put to death for the ahvot.” (Deut. 24:16) The Gemara interprets: fathers shall not be executed because of the testimony of sons, and vice versa.1 Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel (10 BCE-70 CE) said: Do not make light of justice, for it is one of the three legs of the world: justice, truth, and on peace. Therefore, we are to be mindful of not perverting justice as “you can cause the world to shake2 for it (justice) is one of the legs of Hashem’s Throne of Glory. “Righteousness and justice are the foundation of Your throne.” (Psa 85:15) The Proverbs 6:6-8 says, “Go to the ant, you lazy one; consider her halachot, and be wise: They have no guide, overseer, or ruler, yet she; Provides her food in the and gathers her food in the harvest.” The sages teach the ants has three stories in its home. -

Etzion Summer 5775/2015 Update Special Edition from Yeshivat Har Etzion

בסד etzion Summer 5775/2015 UPDATE Special Edition from Yeshivat Har Etzion This edition of the Etzion Update A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY is dedicated to the memory HaRav Aharon Lichtenstein was born on Har Etzion. HaRav Lichtenstein accepted of Yeshivat Har Etzion's Rosh 28 Iyar 5693 (May 23, 1933) in France to the position only on condition that HaRav Yeshiva and spiritual leader, Rabbi Dr. Yechiel and Bluma Lichtenstein. Amital would remain Rosh Yeshiva as HaRav Aharon Lichtenstein zt"l, In 1940, his family had been trapped for well. HaRav Lichtenstein made aliya with who left this world on Rosh several months in Vichy France when Hiram his family in 1971, and HaRav Amital and Chodesh Iyar, 5775. Bingham IV, the American vice consul HaRav Lichtenstein served together as co- in Marseilles, broke American policy by Roshei Yeshiva for four decades and taught granting the Lichtenstein family exit visas thousands of students. to the USA. (Mr. Bingham is known to HaRav Lichtenstein also served as Rector of have saved the lives of some 2,500 Jews Herzog College and as Rosh Kollel of Yeshiva and non-Jews in this way, until he was University's Gruss Institute in Jerusalem. transferred out of France in 1941.) Throughout his career, HaRav Lichtenstein As a young man, HaRav Aharon was combined mastery of the vast expanses of recognized as an outstanding student Torah knowledge with breathtaking analytic at Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin, where he depth and sharpness. His diligence in studied under HaRav Yitzchak Hutner zt"l. He Torah study, day and night, was legendary. -

SYNOPSIS the Mishnah and Tosefta Are Two Related Works of Legal

SYNOPSIS The Mishnah and Tosefta are two related works of legal discourse produced by Jewish sages in Late Roman Palestine. In these works, sages also appear as primary shapers of Jewish law. They are portrayed not only as individuals but also as “the SAGES,” a literary construct that is fleshed out in the context of numerous face-to-face legal disputes with individual sages. Although the historical accuracy of this portrait cannot be verified, it reveals the perceptions or wishes of the Mishnah’s and Tosefta’s redactors about the functioning of authority in the circles. An initial analysis of fourteen parallel Mishnah/Tosefta passages reveals that the authority of the Mishnah’s SAGES is unquestioned while the Tosefta’s SAGES are willing at times to engage in rational argumentation. In one passage, the Tosefta’s SAGES are shown to have ruled hastily and incorrectly on certain legal issues. A broader survey reveals that the Mishnah also contains a modest number of disputes in which the apparently sui generis authority of the SAGES is compromised by their participation in rational argumentation or by literary devices that reveal an occasional weakness of judgment. Since the SAGES are occasionally in error, they are not portrayed in entirely ideal terms. The Tosefta’s literary construct of the SAGES differs in one important respect from the Mishnah’s. In twenty-one passages, the Tosefta describes a later sage reviewing early disputes. Ten of these reviews involve the SAGES. In each of these, the later sage subjects the dispute to further analysis that accords the SAGES’ opinion no more a priori weight than the opinion of individual sages. -

The 5 TOWNS JEWISH TIMES May 30, 2008 23 a Mother’S Musings Let’S Call It a Night

Special Supplement: ISRAEL AT 60 See Pages 37-60 $1.00 WWW.5TJT.COM VOL. 8 NO. 36 25 IYAR 5768 rcsnc ,arp MAY 30, 2008 INSIDE FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK NORPAC MAKES AN IMPACT Praying Like Angels BY LARRY GORDON Yochanan Gordon 26 MindBiz Esther Mann, LMSW 28 Is Losing Winning? Loose Lips What happened to acknowl- into disarray. Hannah Reich Berman 30 edging defeat—not necessarily At this point in the failure, but just that you may Democratic party competition Daf Yomi Insights have been bested or that the for the nomination and oppor- Rabbi Avrohom Sebrow 73 next guy won and you didn’t? tunity to run for President of You don’t have to say you the United States, it certainly World Of Real Estate lost, but at least accede to the would have been in the party’s Anessa V. Cohen 86 notion that you may not have interest for someone to with- Nearly 1,000 people from Jewish communities around the U.S. went to won. This idea of declaring draw—that is, Mrs. Clinton— Washington DC last week as part of the annual NORPAC mission to victory—that is, some kind of and, even if hesitantly and Washington. The event engages senators and congressmen on agenda items including Israel and other subjects important to the American Jewish triumph—regardless of the begrudgingly, support her sen- community. Pictured above (L–R): Shevy Cooperberg, Jodi Cooperberg, reality of defeat is relatively Rabbi Yotav Eliach, Senator Joseph Lieberman, Caroline Stern, David Klatt, new, and it throws a great deal Continued on Page 5 and Trudy Stern. -

THE BENJAMIN and ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld December 2017 • Chanukah 5778

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld December 2017 • Chanukah 5778 Dedicated by Dr. David and Barbara Hurwitz in honor of their children and grandchildren Featuring Divrei Torah from Rabbi Dr. Ari Berman Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm Rabbi Dan Cohen Rabbi Yaakov Neuburger Rabbi Joshua Flug Mrs. Chaya Batya Neugroschl Rabbi Ozer Glickman Mrs. Stephanie Strauss Rabbi Aaron Goldscheider Rabbi Benjamin Yudin Rabbi Akiva Koenigsberg A Project of Yeshiva University’s Center for the Jewish Future 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Chanukah 5778 We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Congregation Ohab Zedek Young Israel of West Hartford, CT New York, NY Century City Los Angeles, CA Beth Jacob Congregation Congregation Beverly Hills, CA Shaarei Tefillah Young Israel of Newton Centre, MA New Hyde Park Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek New Hyde Park, NY Philadelphia, PA Green Road Synagogue Beachwood, OH Young Israel of Congregation Scarsdale Ahavas Achim The Jewish Center Scarsdale, NY Highland Park, NJ New York, NY Young Israel of Congregation Benai Asher Jewish Center of Toco Hills The Sephardic Synagogue Brighton Beach Atlanta, GA of Long Beach Brooklyn, NY Long Beach, NY Young Israel of Koenig Family Foundation Congregation Brooklyn, NY West Hartford Beth Sholom West Hartford, CT Young Israel of Providence, RI Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst Cedarhurst, NY West Hempstead West Hempstead, NY Rabbi Dr.