'The Prince Regent's Role in the Creation And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bargain Booze Limited Wine Rack Limited Conviviality Retail

www.pwc.co.uk In accordance with Paragraph 49 of Schedule B1 of the Insolvency Act 1986 and Rule 3.35 of the Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules 2016 Bargain Booze Limited High Court of Justice Business and Property Courts of England and Wales Date 13 April 2018 Insolvency & Companies List (ChD) CR-2018-002928 Anticipated to be delivered on 16 April 2018 Wine Rack Limited High Court of Justice Business and Property Courts of England and Wales Insolvency & Companies List (ChD) CR-2018-002930 Conviviality Retail Logistics Limited High Court of Justice Business and Property Courts of England and Wales Insolvency & Companies List (ChD) CR-2018-002929 (All in administration) Joint administrators’ proposals for achieving the purpose of administration Contents Abbreviations and definitions 1 Why we’ve prepared this document 3 At a glance 4 Brief history of the Companies and why they’re in administration 5 What we’ve done so far and what’s next if our proposals are approved 10 Estimated financial position 15 Statutory and other information 16 Appendix A: Recent Group history 19 Appendix B: Pre-administration costs 20 Appendix C: Copy of the Joint Administrators’ report to creditors on the pre- packaged sale of assets 22 Appendix D: Estimated financial position including creditors’ details 23 Appendix E: Proof of debt 75 Joint Administrators’ proposals for achieving the purpose of administration Joint Administrators’ proposals for achieving the purpose of administration Abbreviations and definitions The following table shows the abbreviations -

His Royal Highness the Prince Regent of Belgium, the President of The

The Brussels Treaty Five European Nations Brussels, Belgium March 17, 1948 His Royal Highness the Prince Regent of Belgium, the President of the French Republic, President of the French Union, Her Royal Highness the Grand Duchess of Luxembourg, Her Majesty the Queen of the Netherlands and His Majesty The King of Great Britain, Ireland and the British Dominions beyond the Seas, Resolved To reaffirm their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the other ideals proclaimed in the Charter of the United Nations; To fortify and preserve the principles of democracy, personal freedom and political liberty, the constitutional traditions and the rule of law, which are their common heritage; To strengthen, with these aims in view, the economic, social and cultural ties by which they are already united; To co-operate loyally and to co-ordinate their efforts to create in Western Europe a firm basis for European economic recovery; To afford assistance to each other, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, in maintaining international peace and security and in resisting any policy of aggression; To take such steps as may be held to be necessary in the event of a renewal by Germany of a policy of aggression; To associate progressively in the pursuance of these aims other States inspired by the same ideals and animated by the like determination; Desiring for these purposes to conclude a treaty for collaboration in economic, social and cultural matters and for collective self-defence; Have appointed as their Plenipotentiaries: who, having exhibited their full powers found in good and due form, have agreed as follows: ARTICLE I Convinced of the close community of their interests and of the necessity of uniting in order to promote the economic recovery of Europe, the High Contracting Parties will so organize and coordinate their economic activities as to produce the best possible results, by the elimination of conflict in their economic policies, the co-ordination of production and the development of commercial exchanges. -

St James Conservation Area Audit

ST JAMES’S 17 CONSERVATION AREA AUDIT AREA CONSERVATION Document Title: St James Conservation Area Audit Status: Adopted Supplementary Planning Guidance Document ID No.: 2471 This report is based on a draft prepared by B D P. Following a consultation programme undertaken by the council it was adopted as Supplementary Planning Guidance by the Cabinet Member for City Development on 27 November 2002. Published December 2002 © Westminster City Council Department of Planning & Transportation, Development Planning Services, City Hall, 64 Victoria Street, London SW1E 6QP www.westminster.gov.uk PREFACE Since the designation of the first conservation areas in 1967 the City Council has undertaken a comprehensive programme of conservation area designation, extensions and policy development. There are now 53 conservation areas in Westminster, covering 76% of the City. These conservation areas are the subject of detailed policies in the Unitary Development Plan and in Supplementary Planning Guidance. In addition to the basic activity of designation and the formulation of general policy, the City Council is required to undertake conservation area appraisals and to devise local policies in order to protect the unique character of each area. Although this process was first undertaken with the various designation reports, more recent national guidance (as found in Planning Policy Guidance Note 15 and the English Heritage Conservation Area Practice and Conservation Area Appraisal documents) requires detailed appraisals of each conservation area in the form of formally approved and published documents. This enhanced process involves the review of original designation procedures and boundaries; analysis of historical development; identification of all listed buildings and those unlisted buildings making a positive contribution to an area; and the identification and description of key townscape features, including street patterns, trees, open spaces and building types. -

The London Diplomatic List

UNCLASSIFIED THE LONDON DIPLOMATIC LIST Alphabetical list of the representatives of Foreign States & Commonwealth Countries in London with the names & designations of the persons returned as composing their Diplomatic Staff. Representatives of Foreign States & Commonwealth Countries & their Diplomatic Staff enjoy privileges & immunities under the Diplomatic Privileges Act, 1964. Except where shown, private addresses are not available. m Married * Married but not accompanied by wife or husband AFGHANISTAN Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan 31 Princes Gate SW7 1QQ 020 7589 8891 Fax 020 7584 4801 [email protected] www.afghanistanembassy.org.uk Monday-Friday 09.00-16.00 Consular Section 020 7589 8892 Fax 020 7581 3452 [email protected] Monday-Friday 09.00-13.30 HIS EXCELLENCY DR MOHAMMAD DAUD YAAR m Ambassador Extraordinary & Plenipotentiary (since 07 August 2012) Mrs Sadia Yaar Mr Ahmad Zia Siamak m Counsellor Mr M Hanif Ahmadzai m Counsellor Mr Najibullah Mohajer m 1st Secretary Mr M. Daud Wedah m 1st Secretary Mrs Nazifa Haqpal m 2nd Secretary Miss Freshta Omer 2nd Secretary Mr Hanif Aman 3rd Secretary Mrs Wahida Raoufi m 3rd Secretary Mr Yasir Qanooni 3rd Secretary Mr Ahmad Jawaid m Commercial Attaché Mr Nezamuddin Marzee m Acting Military Attaché ALBANIA Embassy of the Republic of Albania 33 St George’s Drive SW1V 4DG 020 7828 8897 Fax 020 7828 8869 [email protected] www.albanianembassy.co.uk HIS EXELLENCY MR MAL BERISHA m Ambassador Extraordinary & Plenipotentiary (since 18 March 2013) Mrs Donika Berisha UNCLASSIFIED S:\Protocol\DMIOU\UNIVERSAL\Administration\Lists of Diplomatic Representation\LDL\RESTORED LDL Master List - Please update this one!.doc UNCLASSIFIED Dr Teuta Starova m Minister-Counsellor Ms Entela Gjika Counsellor Mrs Gentjana Nino m 1st Secretary Dr Xhoana Papakostandini m 3rd Secretary Col. -

Contraception and the Renaissance of Traditional Marriage

CHOOSING A LAW TO LIVE BY ONCE THE KING IS GONE INTRODUCTION Law is the expression of the rules by which civilization governs itself, and it must be that in law as elsewhere will be found the fundamental differences of peoples. Here then it may be that we find the underlying cause of the difference between the civil law and the common law.1 By virtue of its origin, the American legal profession has always been influenced by sources of law outside the United States. American law schools teach students the common law, and law students come to understand that the common law is different than the civil law, which is prevalent in Europe.2 Comparative law courses expose law students to the civil law system by comparing American common law with the law of other countries such as France, which has a civil code.3 A closer look at the history of the American and French Revolutions makes one wonder why the legal systems of the two countries are so different. Certainly, the American and French Revolutions were drastically different in some ways. For instance, the French Revolution was notoriously violent during a period known as “the Terror.”4 Accounts of the French revolutionary government executing so many French citizens as well as the creation of the Cult of the Supreme Being5 make the French Revolution a stark contrast to the American Revolution. Despite the differences, the revolutionary French and Americans shared similar goals—liberty and equality for all citizens and an end to tyranny. Both revolutions happened within approximately two decades of each other and were heavily influenced by the Enlightenment. -

Miss Lisa Brown's Guide to Dressing for a Regency Ball – Gentlemen's

MMiissss LLiissaa BBrroowwnn’’ss GGuuiiddee ttoo DDrreessssiinngg ffoorr aa RReeggeennccyy BBaallll –– GGeennttlleemmeenn’’ss EEddiittiioonn (and remove string!) Shave Jane Austen & the Regency face every Wednesday and The term “Regency” refers to years between 1811 Sunday as per regulations. and 1820 when George III of the United Kingdom was deemed unfit to rule and his son, later George Other types of facial hair IV, was installed as his proxy with the title of were not popular and were “Prince Regent”. However, “Regency Era” is often not allowed in the military. applied to the years between 1795 and 1830. This No beards, mustaches, period is often called the “Extended Regency” goatees, soul patches or because the time shared the same distinctive culture, Van Dykes. fashion, architecture, politics and the continuing Napoleonic War. If you have short hair, brush it forward into a Caesar cut style The author most closely associated with the with no discernable part. If your Regency is Jane Austen (1775-1817). Her witty and hair is long, put it into a pony tail engaging novels are a window into the manners, at the neck with a bow. lifestyle and society of the English gentry. She is the ideal connexion to English Country Dancing as Curly hair for both men and each of her six books: Pride and Prejudice , Sense women was favored over straight and Sensibility , Emma , Persuasion , Mansfield Par k hair. Individual curls were made and Northanger Abbey, feature balls and dances. with pomade (hair gel) and curling papers. Hair If you are unable to assemble much of a Regency wardrobe, you can still look the part by growing your sideburns The Minimum and getting a Caesar cut If you wish to dress the part of a country gentleman hairstyle. -

Licensing Sub-Committee Report

Licensing Sub-Committee City of Westminster Report Item No: Date: 9 July 2020 Licensing Ref No: 20/02820/LIPN - New Premises Licence Title of Report: 94 Great Portland Street London W1W 7NU Report of: Director of Public Protection and Licensing Wards involved: West End Policy context: City of Westminster Statement of Licensing Policy Financial summary: None Report Author: Michelle Steward Senior Licensing Officer Contact details Telephone: 0207 641 6500 Email: [email protected] 1. Application 1-A Applicant and premises Application Type: New Premises Licence, Licensing Act 2003 Application received date: 10 March 2020 Applicant: Where The Pancakes Are Ltd Premises: Where The Pancakes Are Premises address: 94 Great Portland Street Ward: West End Ward London W1W 7NU Cumulative None Impact Area: Premises description: This is an application for a new premises licence to operate as a restaurant with an outside seating area and seeks permission for on and off sales for the sale by retail of alcohol. Premises licence history: As this is a new premises licence application, no premises licence history exists for this premises. Applicant submissions: The applicant has provided a brochure and biography of the company and branding which can be seen at Appendix 3 of this Report. 1-B Proposed licensable activities and hours Late Night Refreshment: Indoors, outdoors or both Both Day: Mon Tues Wed Thur Fri Sat Sun Start: 23:00 23:00 23:00 23:00 23:00 23:00 N/A End: 23:30 23:30 23:30 23:30 00:00 00:00 N/A Seasonal variations/ Non- Sunday before a Bank Holiday Monday: 23:00 hours standard timings: to 00:00 hours. -

![Anecdotes of Celebrities of London and Paris [Electronic Resource]: To](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3494/anecdotes-of-celebrities-of-london-and-paris-electronic-resource-to-543494.webp)

Anecdotes of Celebrities of London and Paris [Electronic Resource]: To

TWO SHILLINGS Captain cSro.noto's Celebrities /m <^I \\BB& ba<*YB S^SSS &eon«ianj»niEk. of UorvtujTi'anti Mam «N. SMITH,. ELBER, i G0. ANECDOTES OF CELEBRITIES OF LONDON AND PARIS, TO WHICH ARE ADDED THE LAST RECOLLECTIONS OF CAPTAIN GRONOW, FORMERLY OF THE FIRST FOOT GUARDS. A NEW EDITION. LONDON: SMITH, ELDER & CO., 15, WATERLOO PLACE. 1870. CONTENTS. PAGE Almack'a in 1815, .... 1 The Duke of Wellington and the Cavalry, 2 The Duke at Carlton House, 4 The Duke and the Author, 4 Wellington's First Campaign, . 8 The Guards and the Umbrellas, 1(J Colonel Freemantle and the Duke's Quarters, 11 A Word for Brown Bess, 12 A Strange Rencontre, .... 13 English and French Soldiers on the Boulevards, 15 " Date obolum Belisario," 16 "Hats off," 16 Hatred of the Prussians by the French Peasantry, 18 Severe Discipline in the Russian Army, 19 The Emperor Alexander in Paris, 2(1 A Fire-Eater Cowed, .... 21 An Insult Rightly Redressed, . 22 A Duel between Two Old Friends, 23 A Duel between Two Officers in the Life Guards, 23 Fayot, the Champion of the Legitimists, 24 The Gardes du Corps, .... 24 The late Marshal Castellane, 28 The late General Gabriel, 31 Admiral de la Susse, .... VI Contents. I'AOK Marshal Lobau, . 34 Montrond, 35 Chateaubriand, . 36 Parson Ambrose, 36 Captain Wilding, 37 The Church Militant, . 38 Louis XVIII., . 38 The Bridge of Jena Saved, 39 Louis XVIII. and Sosth&nes de la Rochefoucauld, 40 The Due de Grammont, 40 The Montmorencies, 42 Ouvrard the Financier, 45 Madame de Stael, 48 A Feminine Foible, 52 Mademoiselle le Xormand, 52 An Ominous Fall, 55 Louis Philippe and Marshal Soult, 55 Decamps and the Duke of Orleans, 56 Fashion in Paris, 57 Literary Salons in France, 64 Sir John Elley, . -

Belgium's Constitution of 1831

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:55 constituteproject.org Belgium's Constitution of 1831 Historical This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:55 Table of contents Preamble . 3 TITLE I: Territory and its Divisions . 3 TITLE II: Belgians and their Rights . 3 TITLE III: Powers . 6 CHAPTER FIRST: THE TWO HOUSES . 7 Section I: The House of Representatives . 8 Section II: The Senate . 9 CHAPTER II: THE KING AND HIS MINISTERS . 10 Section I: The King . 10 Section II: The Ministers . 14 CHAPTER III: JUDICIAL POWER . 15 CHAPTER IV: PROVINCIAL AND COMMUNAL INSTITUTIONS . 17 TITLE IV: Finances . 17 TITLE V: The Army . 19 TITLE VI: General Dispositions . 19 TITLE VII: Constitutional Revision . 20 TITLE VIII: General Disposition . 20 Supplementary Dispositions . 21 Belgium 1831 Page 2 constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:55 • Source of constitutional authority • Preamble Preamble In the name of the Belgian people, the National Congress decrees: TITLE I: Territory and its Divisions Article 1 Belgium is divided into provinces. These provinces are: Antwerp, Brabant, East Flanders, West Flanders, Hainaut, Liege, Limbourg, Luxembourg, Namur, except the relations of Luxembourg with the German Confederation. The territory may be divided by law into a greater number of provinces. Art 2 Subdivisions of the provinces can be established only by law. Art 3 • Accession of territory • Secession of territory The boundaries of the State, of the provinces and of the communes can only be changed or rectified by law. -

U P P E R R I C H M O N D R O

UPPER RICHMOND ROAD CARLTON HOUSE VISION 02-11 PURE 12-25 REFINED 26-31 ELEGANT 32-39 TIMELESS 40-55 SPACE 56-83 01 CARLTON HOUSE – FOREWORD OUR VISION FOR CARLTON HOUSE WAS FOR A NEW KIND OF LANDMARK IN PUTNEY. IT’S A CONTEMPORARY RESIDENCE THAT EMBRACES THE PLEASURES OF A PEACEFUL NEIGHBOURHOOD AND THE JOYS OF ONE OF THE MOST EXCITING CITIES IN THE WORLD. WELCOME TO PUTNEY. WELCOME TO CARLTON HOUSE. NICK HUTCHINGS MANAGING DIRECTOR, COMMERCIAL 03 CARLTON HOUSE – THE VISION The vision behind Carlton House was to create a new gateway to Putney, a landmark designed to stand apart but in tune with its surroundings. The result is a handsome modern residence in a prime spot on Upper Richmond Road, minutes from East Putney Underground and a short walk from the River Thames. Designed by award-winning architects Assael, the striking façade is a statement of arrival, while the stepped shape echoes the rise and fall of the neighbouring buildings. There’s a concierge with mezzanine residents’ lounge, landscaped roof garden and 73 apartments and penthouses, with elegant interiors that evoke traditional British style. While trends come and go, Carlton House is set to be a timeless addition to the neighbourhood. Carlton House UPPER RICHMOND ROAD Image courtesy of Assael 05 CARLTON HOUSE – LOCATION N . London Stadium London Zoo . VICTORIA PARK . Kings Place REGENT’S PARK . The British Library SHOREDITCH . The British Museum . Royal Opera House CITY OF LONDON . WHITE CITY Marble Arch . St Paul’s Cathedral . Somerset House MAYFAIR . Tower of London . Westfield London . HYDE PARK Southbank Centre . -

The House of Coburg and Queen Victoria: a Study of Duty and Affection

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 6-1-1971 The House of Coburg and Queen Victoria: A study of duty and affection Terrence Shellard University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Shellard, Terrence, "The House of Coburg and Queen Victoria: A study of duty and affection" (1971). Student Work. 413. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/413 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOUSE OF COBURG AND QUEEN VICTORIA A STORY OF DUTY AND AFFECTION A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska at Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Terrance She Ha r d June Ip71 UMI Number: EP73051 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Diss««4afor. R_bJ .stung UMI EP73051 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. -

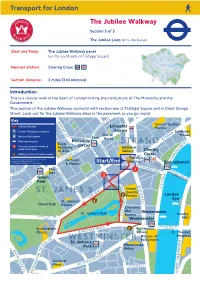

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park.