George IV: Radical Or Reactionary?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Royal Banners 1199–Present

British Royal Banners 1199 – Present Geoff Parsons & Michael Faul Abstract The presentation begins with the (accepted) date of 1199, the death of King Richard I, the first king known to have used the three gold lions on red. It continues to show how King Edward III added the French Royal Arms, consequent to his claim to the French throne. There is then the change from “France Ancient” to “France Modern” by King Henry IV in 1405, which set the pattern of the arms and the standard for the next 198 years. The story then proceeds to show how, over the ensuing 234 years, there were no fewer than six versions of the standard until the adoption of the present pattern in 1837. The presentation includes pictures of all the designs, noting that, in the early stages, the arms appeared more often as a surcoat than a flag. There is also some anecdotal information regarding the various patterns. Anne (1702–1714) Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 799 British Royal Banners 1199 – Present Figure 1 Introduction The presentation begins with the (accepted) date of 1199, the death of King Richard I, the first king known to have used the three gold lions on red. Although we often refer to these flags as Royal Standards, strictly speaking, they are not standard but heraldic banners which are based on the Coats of Arms of the British Monarchs. Figure 2 William I (1066–1087) The first use of the coats of arms would have been exactly that, worn as surcoats by medieval knights. -

Bargain Booze Limited Wine Rack Limited Conviviality Retail

www.pwc.co.uk In accordance with Paragraph 49 of Schedule B1 of the Insolvency Act 1986 and Rule 3.35 of the Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules 2016 Bargain Booze Limited High Court of Justice Business and Property Courts of England and Wales Date 13 April 2018 Insolvency & Companies List (ChD) CR-2018-002928 Anticipated to be delivered on 16 April 2018 Wine Rack Limited High Court of Justice Business and Property Courts of England and Wales Insolvency & Companies List (ChD) CR-2018-002930 Conviviality Retail Logistics Limited High Court of Justice Business and Property Courts of England and Wales Insolvency & Companies List (ChD) CR-2018-002929 (All in administration) Joint administrators’ proposals for achieving the purpose of administration Contents Abbreviations and definitions 1 Why we’ve prepared this document 3 At a glance 4 Brief history of the Companies and why they’re in administration 5 What we’ve done so far and what’s next if our proposals are approved 10 Estimated financial position 15 Statutory and other information 16 Appendix A: Recent Group history 19 Appendix B: Pre-administration costs 20 Appendix C: Copy of the Joint Administrators’ report to creditors on the pre- packaged sale of assets 22 Appendix D: Estimated financial position including creditors’ details 23 Appendix E: Proof of debt 75 Joint Administrators’ proposals for achieving the purpose of administration Joint Administrators’ proposals for achieving the purpose of administration Abbreviations and definitions The following table shows the abbreviations -

St James Conservation Area Audit

ST JAMES’S 17 CONSERVATION AREA AUDIT AREA CONSERVATION Document Title: St James Conservation Area Audit Status: Adopted Supplementary Planning Guidance Document ID No.: 2471 This report is based on a draft prepared by B D P. Following a consultation programme undertaken by the council it was adopted as Supplementary Planning Guidance by the Cabinet Member for City Development on 27 November 2002. Published December 2002 © Westminster City Council Department of Planning & Transportation, Development Planning Services, City Hall, 64 Victoria Street, London SW1E 6QP www.westminster.gov.uk PREFACE Since the designation of the first conservation areas in 1967 the City Council has undertaken a comprehensive programme of conservation area designation, extensions and policy development. There are now 53 conservation areas in Westminster, covering 76% of the City. These conservation areas are the subject of detailed policies in the Unitary Development Plan and in Supplementary Planning Guidance. In addition to the basic activity of designation and the formulation of general policy, the City Council is required to undertake conservation area appraisals and to devise local policies in order to protect the unique character of each area. Although this process was first undertaken with the various designation reports, more recent national guidance (as found in Planning Policy Guidance Note 15 and the English Heritage Conservation Area Practice and Conservation Area Appraisal documents) requires detailed appraisals of each conservation area in the form of formally approved and published documents. This enhanced process involves the review of original designation procedures and boundaries; analysis of historical development; identification of all listed buildings and those unlisted buildings making a positive contribution to an area; and the identification and description of key townscape features, including street patterns, trees, open spaces and building types. -

Erin and Alban

A READY REFERENCE SKETCH OF ERIN AND ALBAN WITH SOME ANNALS OF A BRANCH OF A WEST HIGHLAND FAMILY SARAH A. McCANDLESS CONTENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART I CHAPTER I PRE-HISTORIC PEOPLE OF BRITAIN 1. The Stone Age--Periods 2. The Bronze Age 3. The Iron Age 4. The Turanians 5. The Aryans and Branches 6. The Celto CHAPTER II FIRST HISTORICAL MENTION OF BRITAIN 1. Greeks 2. Phoenicians 3. Romans CHAPTER III COLONIZATION PE}RIODS OF ERIN, TRADITIONS 1. British 2. Irish: 1. Partholon 2. Nemhidh 3. Firbolg 4. Tuatha de Danan 5. Miledh 6. Creuthnigh 7. Physical CharacteriEtics of the Colonists 8. Period of Ollaimh Fodhla n ·'· Cadroc's Tradition 10. Pictish Tradition CHAPTER IV ERIN FROM THE 5TH TO 15TH CENTURY 1. 5th to 8th, Christianity-Results 2. 9th to 12th, Danish Invasions :0. 12th. Tribes and Families 4. 1169-1175, Anglo-Norman Conquest 5. Condition under Anglo-Norman Rule CHAPTER V LEGENDARY HISTORY OF ALBAN 1. Irish sources 2. Nemedians in Alban 3. Firbolg and Tuatha de Danan 4. Milesians in Alban 5. Creuthnigh in Alban 6. Two Landmarks 7. Three pagan kings of Erin in Alban II CONTENTS CHAPTER VI AUTHENTIC HISTORY BEGINS 1. Battle of Ocha, 478 A. D. 2. Dalaradia, 498 A. D. 3. Connection between Erin and Alban CHAPTER VII ROMAN CAMPAIGNS IN BRITAIN (55 B.C.-410 A.D.) 1. Caesar's Campaigns, 54-55 B.C. 2. Agricola's Campaigns, 78-86 A.D. 3. Hadrian's Campaigns, 120 A.D. 4. Severus' Campaigns, 208 A.D. 5. State of Britain During 150 Years after SeveTus 6. -

Copyrighted Material

33_056819 bindex.qxp 11/3/06 11:01 AM Page 363 Index fighting the Vikings, 52–54 • A • as law-giver, 57–58 Aberfan tragedy, 304–305 literary interests, 56–57 Act of Union (1707), 2, 251 reforms of, 54–55 Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, queen of reign of, 50, 51–52 William IV, 268, 361 Alfred, son of King Aethelred, king of Áed, king of Scotland, 159 England, 73, 74 Áed Findliath, ruler in Ireland, 159 Ambrosius Aurelianus (Roman leader), 40 Aedán mac Gabráin, overking of Dalriada, 153 Andrew, Prince, Duke of York (son of Aelfflaed, queen of Edward, king Elizabeth II) of Wessex, 59 birth of, 301 Aelfgifu of Northampton, queen of Cnut, 68 as naval officer, 33 Aethelbald, king of Mercia, 45 response to death of Princess Diana, 313 Aethelbert, king of Wessex, 49 separation from Sarah, Duchess of York, Aethelflaed, daughter of Alfred, king of 309 Wessex, 46 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 57, 58, 63 Aethelfrith, Saxon king, 43 Anglo-Saxons Aethelred, king of England, 51, 65–66 appointing an heir, 16 Aethelred, king of Mercia, 45, 46, 55 invasion of Britain, 39–41 Aethelred, king of Wessex, 50 kingdoms of, 37, 42 Aethelstan, king of Wessex, 51, 61–62 kings of, 41–42 Aethelwold, son of Aethelred, king of overview, 12 Wessex, 60 Anna, queen of Scotland, 204 Aethelwulf, king of Wessex, 49 Anne, Princess Royal, daughter of Africa, as part of British empire, 14 Elizabeth II, 301, 309 Agincourt, battle of, 136–138 Anne, queen of England Albert, Prince, son of George V, later lack of heir, 17 George VI, 283, 291 marriage to George of Denmark, 360–361 Albert of -

U P P E R R I C H M O N D R O

UPPER RICHMOND ROAD CARLTON HOUSE VISION 02-11 PURE 12-25 REFINED 26-31 ELEGANT 32-39 TIMELESS 40-55 SPACE 56-83 01 CARLTON HOUSE – FOREWORD OUR VISION FOR CARLTON HOUSE WAS FOR A NEW KIND OF LANDMARK IN PUTNEY. IT’S A CONTEMPORARY RESIDENCE THAT EMBRACES THE PLEASURES OF A PEACEFUL NEIGHBOURHOOD AND THE JOYS OF ONE OF THE MOST EXCITING CITIES IN THE WORLD. WELCOME TO PUTNEY. WELCOME TO CARLTON HOUSE. NICK HUTCHINGS MANAGING DIRECTOR, COMMERCIAL 03 CARLTON HOUSE – THE VISION The vision behind Carlton House was to create a new gateway to Putney, a landmark designed to stand apart but in tune with its surroundings. The result is a handsome modern residence in a prime spot on Upper Richmond Road, minutes from East Putney Underground and a short walk from the River Thames. Designed by award-winning architects Assael, the striking façade is a statement of arrival, while the stepped shape echoes the rise and fall of the neighbouring buildings. There’s a concierge with mezzanine residents’ lounge, landscaped roof garden and 73 apartments and penthouses, with elegant interiors that evoke traditional British style. While trends come and go, Carlton House is set to be a timeless addition to the neighbourhood. Carlton House UPPER RICHMOND ROAD Image courtesy of Assael 05 CARLTON HOUSE – LOCATION N . London Stadium London Zoo . VICTORIA PARK . Kings Place REGENT’S PARK . The British Library SHOREDITCH . The British Museum . Royal Opera House CITY OF LONDON . WHITE CITY Marble Arch . St Paul’s Cathedral . Somerset House MAYFAIR . Tower of London . Westfield London . HYDE PARK Southbank Centre . -

Revolutionary Betrayal: the Fall of King George III in the Experience Of

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY REVOLUTIONARY BETRAYAL: THE FALL OF KING GEORGE III IN THE EXPERIENCE OF POLITICIANS, PLANTERS, AND PREACHERS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE HISTORY DEPARTMENT IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF HISTORY BY BENJAMIN J. BARLOWE LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA APRIL 2013 Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: “Great Britain May Thank Herself:” King George III, Congressional Delegates, and American Independence, 1774-1776 .................................... 11 Chapter 2: Master and Slave, King and Subject: Southern Planters and the Fall of King George III ....................................................................................... 41 Chapter 3: “No Trace of Papal Bondage:” American Patriot Ministers and the Fall of King George III ................................................................................ 62 Conclusion ........................................................................................................ 89 Bibliography ...................................................................................................... 94 1 Introduction When describing the imperial crisis of 1763-1776 between the British government and the American colonists, historians often refer to Great Britain as a united entity unto itself, a single character in the imperial conflict. While this offers rhetorical benefits, it oversimplifies the complex constitutional relationship between the American -

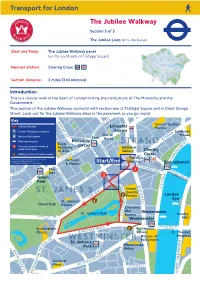

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park. -

How Enlightened Was George III? the King, the British Museum and the Enlightenment Robert Lacey

How enlightened was George III? The King, the British Museum and the Enlightenment Robert Lacey 18 October 2004 Robert Lacey set out to debunk what he sees as the ‘myth’ of George III as the greatest of all royal patrons of the British Museum. As is well known, the king assembled one of the great book collections of the eighteenth century. After his death, his son, George IV, attempted to sell it, but, perhaps swayed by the offer of government funding for the rebuilding of the Queen’s House, he was persuaded to present the books to the Museum. There the collection joined the Old Royal Library, which had been given to the Museum by George II as one of the foundation collections. The ‘King’s Library’ is now the appropriate symbolic centrepiece of the British Library building. Sometimes explicitly and more often implicitly, historians have assumed that George III had always intended that the books should go to the British Museum, but, as Lacey showed, there is no real evidence that this was what he ever envisaged. The collection was instead a working library suitable for an enlightened monarch and assembled mainly with the aim of assisting that particular monarch in the task of governing his kingdom. To clinch his argument, Lacey revealed his latest discoveries from the Royal Archives. Like those of all British monarchs, the will of George III has never been released to historians. That remains the case. However, the Royal Archives have disclosed to Lacey what George III’s will says about his book collection. -

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION the Effects of the Industrial Revolution

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION The effects of the Industrial Revolution. The 18th century was characterized by many events: the rise of the Middle classes, the development of commercial activities, both the growth of industries and banks, and total changes in life-style. The bourgeoisie, although still excluded from political power, played an increasingly influential part in the cultural life of the country, influencing tastes and attitudes in a way which is unique to British culture. In particular the period between 1688 and the middle of the 18th century, pervaded with a relative political stability, was marked by the profound changes that led to the transformation of England from an agricultural country into a great manufacturing and commercial power. It was a gradual and complex process caused by a chain of connected factors and events. The wars of the 18th century were followed by the acquisition of a vast colonial empire, whose growth in wealth and population opened new markets to English goods. The English established their rule in India after the Battle of Plassey in 1757, and in Canada British predominance was assured by the Capture of Quebec in 1759. Within a short time the small-scale hand production of home industry began to prove inadequate to further developments. The continuous increase of the English trade, in concentrating huge profits in the hands of an ambitious upper middle class, mostly composed of affluent merchants, led to a vast accumulation of capitals to be profitably used. The flourishing trade and the economic advancement of the nation invested agriculture; the old system of agriculture of subsistence, based on small-scale farming, was to reveal itself incompatible with the exigencies of an expanding market and the growth of population. -

Wilhelm Ii, Edward Vii, and Anglo-German Relations, 1888-1910

ROYAL PAINS: WILHELM II, EDWARD VII, AND ANGLO-GERMAN RELATIONS, 1888-1910 A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Christopher M. Bartone August, 2012 ROYAL PAINS: WILHELM II, EDWARD VII, AND ANGLO-GERMAN RELATIONS, 1888-1910 Christopher M. Bartone Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Shelley Baranowski Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Stephen Harp Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ Department Chair Date Dr. Martin Wainwright ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………1 II. FAMILY TIES................................................................................................................9 Edward and Queen Victoria……………………………………………………….9 Wilhelm and Queen Victoria…………………………………………………….13 Bertie and Willy………………………………………………………………….17 Relations with Other Heads of State…………………………………………….23 III. PARADIGM SHIFT…………………………………………………………………30 Anglo-German Relations, 1888-1900……………………………………………30 King Edward’s Diplomacy………………………………………………………35 The Russo-Japanese War and Beyond………………………………………….39 IV. CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………………51 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………56 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Scholars view the Anglo-German rivalry of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century, -

'X'marks the Spot: the History and Historiography of Coleshill House

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Department of History ‘X’ Marks the Spot: The History and Historiography of Coleshill House, Berkshire by Karen Fielder Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2012 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Doctor of Philosophy ‘X’ MARKS THE SPOT: THE HISTORY AND HISTORIOGRAPHY OF COLESHILL HOUSE, BERKSHIRE by Karen Fielder Coleshill House was a much admired seventeenth-century country house which the architectural historian John Summerson referred to as ‘a statement of the utmost value to British architecture’. Following a disastrous fire in September 1952 the remains of the house were demolished amidst much controversy shortly before the Coleshill estate including the house were due to pass to the National Trust. The editor of The Connoisseur, L.G.G. Ramsey, published a piece in the magazine in 1953 lamenting the loss of what he described as ‘the most important and significant single house in England’. ‘Now’, he wrote, ‘only X marks the spot where Coleshill once stood’. Visiting the site of the house today on the Trust’s Coleshill estate there remains a palpable sense of the absent building. This thesis engages with the house that continues to exist in the realm of the imagination, and asks how Coleshill is brought to mind not simply through the visual signals that remain on the estate, but also through the mental reckoning resulting from what we know and understand of the house. In particular, this project explores the complexities of how the idea of Coleshill as a canonical work in British architectural histories was created and sustained over time.