British Royal Banners 1199–Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eflags03.Pdf

ISSUE 3 March 2007 Greetings all Flag Institute members and welcome to our third edition of eFlags. As you can see we have developed our logo a bit now….at least it’s memorable! This edition seems to have developed something of an African theme growing out of the chairman’s visit to the cinema to see the ‘Last King of Scotland’ (an amazing and flesh cringing film…well worth a visit by the way). Events have also moved fast in the Institute’s development, and we hope the final section will keep you all in touch. Please do think about coming to one of our meetings, they are great fun, ( its one of the few occasions when you can talk about flags and not face the ridicule of your family or friends!) and we have a line up of some fascinating presentations. As always any comments or suggestions would be gratefully received at [email protected] . THE EMPEROR, THE MIGHTY WARRIOR & THE LORD OF THE ALL THE BEASTS page 2 NEW FLAG DISCOVERED page 9 FLAGS IN THE NEWS page 10 SITES OF VEXILLOGICAL INTEREST page 11 PUTTING A FACE ON FLAGS page 12 FLAG INSTITUTE EVENTS page 13 NEW COUNCIL MEMBERS page 14 HOW TO GET IN TOUCH WITH THE INSTITUTE page 15 1 The Emperor, the Mighty Warrior and the Lord of All the Beasts. The 1970s in Africa saw the rise of a number of ‘colourful’ figures in the national histories of various countries. Of course the term ‘colourful’ here is used to mean that very African blend of an eccentric figure of fun, with brutal psychopath. -

Guidance on the Use of Royal Arms, Names and Images

GUIDANCE ON THE USE OF ROYAL ARMS, NAMES AND IMAGES 1 The following booklet summarises the legal position governing the use, for commercial purposes, of the Royal Arms, Royal Devices, Emblems and Titles and of photographs, portraits, engravings, effigies and busts of The Queen and Members of the Royal Family. Guidance on advertising in which reference is made to a Member of the Royal Family, and on the use of images of Members of the Royal Family on articles for sale, is also provided. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office will be pleased to provide guidance when it is unclear as to whether the use of “Arms” etc., may give the impression that there is a Royal connection. 2 TRADE MARKS Section 4 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 states: “A trade mark which consists of or contains – (a) the Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it, (b) a representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags, (c) a representation of Her Majesty or any Member of the Royal Family, or any colourable imitation thereof, or (d) words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation, shall not be registered unless it appears to the registrar that consent has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or, as the case may be, the relevant Member of the Royal Family.” The Lord Chamberlain's Office is empowered to grant the consent referred to in Section 4(1) on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen. -

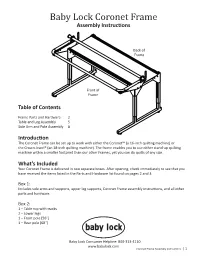

Coronet (BLCT16) Frame Assembly Instructions REVISED

8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 REVISIONS ECO REV. DESCRIPTION DATE APPROVED A INITIAL RELEASE D D Baby Lock Coronet Frame Assembly Instructions Back of Frame C C Front of Frame Table of Contents Frame Parts and Hardware 2 BILL OF MATERIALS ENG-10007 Table and Leg Assembly 5 ITEM PART NUMBER DESCRIPTION QTY. Side Arm and Pole Assembly 8 1 QF05300-300 TABLE ASSY, TACONY FRAME 1 2 QF05300-402 CORNER HEIGHT BAR, A 2 B Introduction 3 QF05300-403 CORNER HEIGHT BAR, B 2 B The Coronet Frame can be set up to work with either the Coronet™ (a 16-inch quilting machine) or 4 QF05300-401 END LEG STAND 2 the Crown Jewel® (an 18-inch quilting machine). The frame enables you to use either stand-up quilting 5 QF09318-303 SCREW-M6x12 SWH 6 machine within a smaller footprint than our other Frames, yet you can do quilts of any size. 6 QF09318-07 Screw-M8x16 SBHCS 16 7 QF09318-108 LEVELING GLIDE 4 What’s Included 8 ENG-10005 ASSY-SIDE ARM RIGHT LF 1 Your Coronet Frame is delivered in two separate boxes. After opening, check immediately to see that you 9 ENG-10006 ASSY-SIDE ARM LEFT LF 1 have received the items listed in the Parts and Hardware list found on pages 2 and 3. 10 QF10005 POLE FRONT LF 1 11 QF10009 POLE REAR LF 1 Box 1: 12 QF10011 END CAP-REAR POLE LF 2 Includes side arms and supports, upper leg supports, Coronet Frame assembly instructions, and all other UNLESS OTHERWISE SPECIFIED: NAME DATE parts and hardware. -

Vexillum, June 2018, No. 2

Research and news of the North American Vexillological Association June 2018 No. Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie Juin 2018 2 INSIDE Page Editor’s Note 2 President’s Column 3 NAVA Membership Anniversaries 3 The Flag of Unity in Diversity 4 Incorporating NAVA News and Flag Research Quarterly Book Review: "A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols" 7 New Flags: 4 Reno, Nevada 8 The International Vegan Flag 9 Regional Group Report: The Flag of Unity Chesapeake Bay Flag Association 10 Vexi-News Celebrates First Anniversary 10 in Diversity Judge Carlos Moore, Mississippi Flag Activist 11 Stamp Celebrates 200th Anniversary of the Flag Act of 1818 12 Captain William Driver Award Guidelines 12 The Water The Water Protectors: Native American Nationalism, Environmentalism, and the Flags of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protectors Protests of 2016–2017 13 NAVA Grants 21 Evolutionary Vexillography in the Twenty-First Century 21 13 Help Support NAVA's Upcoming Vatican Flags Book 23 NAVA Annual Meeting Notice 24 Top: The Flag of Unity in Diversity Right: Demonstrators at the NoDAPL protests in January 2017. Source: https:// www.indianz.com/News/2017/01/27/delay-in- nodapl-response-points-to-more.asp 2 | June 2018 • Vexillum No. 2 June / Juin 2018 Number 2 / Numéro 2 Editor's Note | Note de la rédaction Dear Reader: We hope you enjoyed the premiere issue of Vexillum. In addition to offering my thanks Research and news of the North American to the contributors and our fine layout designer Jonathan Lehmann, I owe a special note Vexillological Association / Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine of gratitude to NAVA members Peter Ansoff, Stan Contrades, Xing Fei, Ted Kaye, Pete de vexillologie. -

STELLAR FLAGS by Scott Mainwaring Stellar Flags 1 Tion of That Word

Portland Flag Association Publication 1 Portland Flag Association ―Free, and Worth Every Penny!‖ Issue 11 October 2006 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: STELLAR FLAGS By Scott Mainwaring Stellar Flags 1 tion of that word. Never mind that real stars are twinkling point sources Pirate Flags 2 Flag design has long looked to the natural world and its phenomena as a of light (except for certain stars ob- Some Flag Related Websites 3 source of inspiration and symbolism. served through powerful telescopes October 2006 Flutterings 3 Much of this vocabulary is earth- which can resolve an actual disc of Next Meeting Announcement 4 bound, making use of plants, ani- light) that bear, at most, a very rough Flags in the News 4 mals, and landscape features. But resemblance to the decagonal shapes Correction 4 perhaps as much of it is celestial, one learns to draw as a child. Just The Flag Quiz 7 making use of astronomical objects say that it‘s our cultural convention to depict stars in this way, and that like the Sun, the Moon, and the stars – this last being the focus of this arti- depiction of a natural object is what cle. Let's call a flag with such a rela- indeed is going on in almost all cases. tionship a stellar flag. At first glance, This may be the case, but if so, this is ―stellar flag‖ is a huge category – a very weak sense of ―stellar.‖ It stars on flags are in no short supply. seems more apt to say that, even if As a rough (under-) estimate, originally inspired by the natural as- Wikipedia (as of 10/4/06) lists 403 tronomical object, most stars on current and historical flags with one most flags (like most stars in most or more stars. -

Erin and Alban

A READY REFERENCE SKETCH OF ERIN AND ALBAN WITH SOME ANNALS OF A BRANCH OF A WEST HIGHLAND FAMILY SARAH A. McCANDLESS CONTENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART I CHAPTER I PRE-HISTORIC PEOPLE OF BRITAIN 1. The Stone Age--Periods 2. The Bronze Age 3. The Iron Age 4. The Turanians 5. The Aryans and Branches 6. The Celto CHAPTER II FIRST HISTORICAL MENTION OF BRITAIN 1. Greeks 2. Phoenicians 3. Romans CHAPTER III COLONIZATION PE}RIODS OF ERIN, TRADITIONS 1. British 2. Irish: 1. Partholon 2. Nemhidh 3. Firbolg 4. Tuatha de Danan 5. Miledh 6. Creuthnigh 7. Physical CharacteriEtics of the Colonists 8. Period of Ollaimh Fodhla n ·'· Cadroc's Tradition 10. Pictish Tradition CHAPTER IV ERIN FROM THE 5TH TO 15TH CENTURY 1. 5th to 8th, Christianity-Results 2. 9th to 12th, Danish Invasions :0. 12th. Tribes and Families 4. 1169-1175, Anglo-Norman Conquest 5. Condition under Anglo-Norman Rule CHAPTER V LEGENDARY HISTORY OF ALBAN 1. Irish sources 2. Nemedians in Alban 3. Firbolg and Tuatha de Danan 4. Milesians in Alban 5. Creuthnigh in Alban 6. Two Landmarks 7. Three pagan kings of Erin in Alban II CONTENTS CHAPTER VI AUTHENTIC HISTORY BEGINS 1. Battle of Ocha, 478 A. D. 2. Dalaradia, 498 A. D. 3. Connection between Erin and Alban CHAPTER VII ROMAN CAMPAIGNS IN BRITAIN (55 B.C.-410 A.D.) 1. Caesar's Campaigns, 54-55 B.C. 2. Agricola's Campaigns, 78-86 A.D. 3. Hadrian's Campaigns, 120 A.D. 4. Severus' Campaigns, 208 A.D. 5. State of Britain During 150 Years after SeveTus 6. -

Make Your Own Lion and Unicorn Puppets

Scotland’s historic properties feature lots of lions and unicorns – they’re in Scotland’s royal coat of arms. Lions were thought to represent bravery and strength – the king of the animal world. The unicorn has been a Scottish royal symbol for around 600 years and – believe it or not – is Scotland’s national animal. Unicorns symbolised innocence and power. People considered them wild and untamed, so they’re often shown chained around their neck. When James VI of Scotland unified Scotland and England in 1603, he changed his coat of arms to include one unicorn and one lion either side of a shield. TOP TIPS FOR MAKING YOUR PUPPETS This activity ideally needs a printer and some brass paper fasteners. If you don’t have a printer, why not use the templates as inspiration for drawing your own versions! And if you don’t have paper fasteners (split pins), you could experiment with tying a big knot in some string or wool, threading the string through a small hole in your papers (a hole punch would create too big a hole) and tying another big knot on the other side. If you’ve got beads or buttons you could also use these to secure the wire/string/wool either side of the paper body parts you’re attaching together. The lion that greets The unicorn from visitors arriving at the King’s Fountain Edinburgh Castle. at Linlithgow Palace. Resource created for Historic Environment Scotland by artist Hannah Ayre. 1. Print out the template onto 2. Cut out the shapes card or print onto paper, then glue onto card such as a cereal box, then colour in the shapes. -

Browsing Through Bias: the Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings for African American Studies and LGBTQIA Studies

Browsing through Bias: The Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings for African American Studies and LGBTQIA Studies Sara A. Howard and Steven A. Knowlton Abstract The knowledge organization system prepared by the Library of Con- gress (LC) and widely used in academic libraries has some disadvan- tages for researchers in the fields of African American studies and LGBTQIA studies. The interdisciplinary nature of those fields means that browsing in stacks or shelflists organized by LC Classification requires looking in numerous locations. As well, persistent bias in the language used for subject headings, as well as the hierarchy of clas- sification for books in these fields, continues to “other” the peoples and topics that populate these titles. This paper offers tools to help researchers have a holistic view of applicable titles across library shelves and hopes to become part of a larger conversation regarding social responsibility and diversity in the library community.1 Introduction The neat division of knowledge into tidy silos of scholarly disciplines, each with its own section of a knowledge organization system (KOS), has long characterized the efforts of libraries to arrange their collections of books. The KOS most commonly used in American academic libraries is the Li- brary of Congress Classification (LCC). LCC, developed between 1899 and 1903 by James C. M. Hanson and Charles Martel, is based on the work of Charles Ammi Cutter. Cutter devised his “Expansive Classification” to em- body the universe of human knowledge within twenty-seven classes, while Hanson and Martel eventually settled on twenty (Chan 1999, 6–12). Those classes tend to mirror the names of academic departments then prevail- ing in colleges and universities (e.g., Philosophy, History, Medicine, and Agriculture). -

Heraldic Terms

HERALDIC TERMS The following terms, and their definitions, are used in heraldry. Some terms and practices were used in period real-world heraldry only. Some terms and practices are used in modern real-world heraldry only. Other terms and practices are used in SCA heraldry only. Most are used in both real-world and SCA heraldry. All are presented here as an aid to heraldic research and education. A LA CUISSE, A LA QUISE - at the thigh ABAISED, ABAISSÉ, ABASED - a charge or element depicted lower than its normal position ABATEMENTS - marks of disgrace placed on the shield of an offender of the law. There are extreme few records of such being employed, and then only noted in rolls. (As who would display their device if it had an abatement on it?) ABISME - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ABOUTÉ - end to end ABOVE - an ambiguous term which should be avoided in blazon. Generally, two charges one of which is above the other on the field can be blazoned better as "in pale an X and a Y" or "an A and in chief a B". See atop, ensigned. ABYSS - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ACCOLLÉ - (1) two shields side-by-side, sometimes united by their bottom tips overlapping or being connected to each other by their sides; (2) an animal with a crown, collar or other item around its neck; (3) keys, weapons or other implements placed saltirewise behind the shield in a heraldic display. -

The Colours of the Fleet

THE COLOURS OF THE FLEET TCOF BRITISH & BRITISH DERIVED ENSIGNS ~ THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE WORLDWIDE LIST OF ALL FLAGS AND ENSIGNS, PAST AND PRESENT, WHICH BEAR THE UNION FLAG IN THE CANTON “Build up the highway clear it of stones lift up an ensign over the peoples” Isaiah 62 vv 10 Created and compiled by Malcolm Farrow OBE President of the Flag Institute Edited and updated by David Prothero 15 January 2015 © 1 CONTENTS Chapter 1 Page 3 Introduction Page 5 Definition of an Ensign Page 6 The Development of Modern Ensigns Page 10 Union Flags, Flagstaffs and Crowns Page 13 A Brief Summary Page 13 Reference Sources Page 14 Chronology Page 17 Numerical Summary of Ensigns Chapter 2 British Ensigns and Related Flags in Current Use Page 18 White Ensigns Page 25 Blue Ensigns Page 37 Red Ensigns Page 42 Sky Blue Ensigns Page 43 Ensigns of Other Colours Page 45 Old Flags in Current Use Chapter 3 Special Ensigns of Yacht Clubs and Sailing Associations Page 48 Introduction Page 50 Current Page 62 Obsolete Chapter 4 Obsolete Ensigns and Related Flags Page 68 British Isles Page 81 Commonwealth and Empire Page 112 Unidentified Flags Page 112 Hypothetical Flags Chapter 5 Exclusions. Page 114 Flags similar to Ensigns and Unofficial Ensigns Chapter 6 Proclamations Page 121 A Proclamation Amending Proclamation dated 1st January 1801 declaring what Ensign or Colours shall be borne at sea by Merchant Ships. Page 122 Proclamation dated January 1, 1801 declaring what ensign or colours shall be borne at sea by merchant ships. 2 CHAPTER 1 Introduction The Colours of The Fleet 2013 attempts to fill a gap in the constitutional and historic records of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth by seeking to list all British and British derived ensigns which have ever existed. -

Town Unveils New Flag & Coat of Arms

TOWN UNVEILS NEW FLAG & COAT OF ARMS For Immediate Release December 10, 2013 Niagara-on-the-Lake - Lord Mayor, accompanied by the Right Reverend D. Ralph Spence, Albion Herald Extraordinary, officially unveiled a new town flag and coat of arms today before an audience at the Courthouse. Following the official proclamation ceremony, a procession, led by the Fort George Fife & Drum Corps and completed by an honour guard from the 809 Newark Squadron Air Cadets, witnessed the raising of the flag. The procession then continued on to St. Mark’s Church for a special service commemorating the Burning of Niagara. “We thought this was a fitting date to introduce a symbol of hope and promise given the devastation that occurred exactly 200 years to the day, the burning of our town,” stated Lord Mayor Eke. “From ashes comes rebirth and hope.” The new flag, coat of arms and badge have been granted by the Chief Herald of Canada, Dr. Claire Boudreau, Director of the Canadian Heraldic Authority within the office of the Governor General. Bishop Spence, who served as Bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Niagara from 1998 - 2008, represented the Chief Herald and read the official proclamation. He is one of only four Canadians who hold the title of herald extraordinary. A description of the new coat of arms, flag and badge, known as armorial bearings in heraldry, is attached. For more information, please contact: Dave Eke, Lord Mayor 905-468-3266 Symbolism of the Armorial Bearings of The Corporation of the Town of Niagara-on-the-Lake Arms: The colours refer to the Royal Union Flag. -

Copyrighted Material

33_056819 bindex.qxp 11/3/06 11:01 AM Page 363 Index fighting the Vikings, 52–54 • A • as law-giver, 57–58 Aberfan tragedy, 304–305 literary interests, 56–57 Act of Union (1707), 2, 251 reforms of, 54–55 Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, queen of reign of, 50, 51–52 William IV, 268, 361 Alfred, son of King Aethelred, king of Áed, king of Scotland, 159 England, 73, 74 Áed Findliath, ruler in Ireland, 159 Ambrosius Aurelianus (Roman leader), 40 Aedán mac Gabráin, overking of Dalriada, 153 Andrew, Prince, Duke of York (son of Aelfflaed, queen of Edward, king Elizabeth II) of Wessex, 59 birth of, 301 Aelfgifu of Northampton, queen of Cnut, 68 as naval officer, 33 Aethelbald, king of Mercia, 45 response to death of Princess Diana, 313 Aethelbert, king of Wessex, 49 separation from Sarah, Duchess of York, Aethelflaed, daughter of Alfred, king of 309 Wessex, 46 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 57, 58, 63 Aethelfrith, Saxon king, 43 Anglo-Saxons Aethelred, king of England, 51, 65–66 appointing an heir, 16 Aethelred, king of Mercia, 45, 46, 55 invasion of Britain, 39–41 Aethelred, king of Wessex, 50 kingdoms of, 37, 42 Aethelstan, king of Wessex, 51, 61–62 kings of, 41–42 Aethelwold, son of Aethelred, king of overview, 12 Wessex, 60 Anna, queen of Scotland, 204 Aethelwulf, king of Wessex, 49 Anne, Princess Royal, daughter of Africa, as part of British empire, 14 Elizabeth II, 301, 309 Agincourt, battle of, 136–138 Anne, queen of England Albert, Prince, son of George V, later lack of heir, 17 George VI, 283, 291 marriage to George of Denmark, 360–361 Albert of