Volume 8/ Number 2 May 2021 Article 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Report on the Mapping Study of Peace & Security Engagement In

A Report on the Mapping Study of Peace & Security Engagement in African Tertiary Institutions Written by Funmi E. Vogt This project was funded through the support of the Carnegie Corporation About the African Leadership Centre In July 2008, King’s College London through the Conflict, Security and Development group (CSDG), established the African Leadership Centre (ALC). In June 2010, the ALC was officially launched in Nairobi, Kenya, as a joint initiative of King’s College London and the University of Nairobi. The ALC aims to build the next generation of scholars and analysts on peace, security and development. The idea of an African Leadership Centre was conceived to generate innovative ways to address some of the challenges faced on the African continent, by a new generation of “home‐grown” talent. The ALC provides mentoring to the next generation of African leaders and facilitates their participation in national, regional and international efforts to achieve transformative change in Africa, and is guided by the following principles: a) To foster African‐led ideas and processes of change b) To encourage diversity in terms of gender, region, class and beliefs c) To provide the right environment for independent thinking d) Recognition of youth agency e) Pursuit of excellence f) Integrity The African Leadership Centre mentors young Africans with the potential to lead innovative change in their communities, countries and across the continent. The Centre links academia and the real world of policy and practice, and aims to build a network of people who are committed to the issue of Peace and Security on the continent of Africa. -

Participants 2Day Workshop Ghana

AIR Centre two-day Maker Workshop: Design Innovation for Coastal Resilience Accra, Ghana October 19th-20th, 2018 List of Participants Alberta Danso - Ashesi University Alexander Denkyi - Ashesi University Anita Antwiwaa - Space Systems Technology Lab / All Nations University College Benjamin Bonsu - Space Systems Technology Lab / All Nations University College Bryan Achiampong - Ashesi University Christopher Anamalia - Ashesi University D. K. Osseo-Asare - Penn State Danyuo Yiporo - Ashesi University Ernest Opoku-Kwarteng - Centre for Remote Sensing and Geographic Information Services (CERSGIS) Ernest Teye Matey - Space Systems Technology Lab / All Nations University College Faka Nsadisa - South African Development Community – Climate Services Centre (SADC-CSC) Foster Mensah - Centre for Remote Sensing and Geographic Information Services (CERSGIS) Francis Smita - Namibia Institute of Space Technology (NIST) / Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST) G. Ayorkor Korsah - Head of Department of Computer Science / Ashesi University Gameli Magnus Kwaku Adzaho - Next Einstein Forum AIR Centre two-day Maker Workshop: Design Innovation for Coastal Resilience 1 Accra, Ghana George Senyo Owusu - Centre for Remote Sensing and Geographic Information Services (CERSGIS) Gordon Adomdza - Ashesi University/D:Lab Gregory Jenkins - Penn State Hannah Lormenyo - Ashesi University Ivana Ayorkor Barley - Ashesi University Joseph Neenyi Quansah - Space Systems Technology Lab / All Nations University College Kenobi Morris - Ashesi University Kristen -

Private Universities

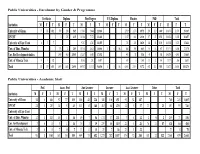

Public Universities - Enrolment by Gender & Programme Certificate Diploma First Degree P.G Diploma Masters PhD Total Institution M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T University of Ghana 97 315 412 309 256 565 13,340 9,604 22,944 2,399 1,576 3,975 290 119 409 16,435 11,870 28,305 KNUST 0 215 215 16,188 7,272 23,460 2,147 683 2,830 117 35 152 18,452 8,205 26,657 University of Cape Coast 4 3 7 9,707 4,748 14,455 735 285 1,020 104 34 138 10,550 5,070 15,620 Univ. of Educ. Winneba 133 72 205 11,194 4,812 16,006 11 5 16 564 301 865 69 18 87 11,971 5,208 17,179 Unv. For Development studies 1,045 460 1,505 13,287 4,305 17,592 443 71 514 49 5 54 14,824 4,841 19,665 Univ. of Mines& Tech. 31 1 32 1,186 251 1,437 147 6 153 13 2 15 1,377 260 1,637 Total 132 319 451 1,487 1,003 2,490 64,902 31,192 96,094 11 5 16 6,453 2,919 9,372 642 213 855 73,627 35,651 109,278 Public Universities - Academic Staff Prof. Assoc. Prof. Snr. Lecturer Lecturer Asst. Lecturer Tutor Total Institution M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T University of Ghana 54 6 60 92 27 119 180 48 228 341 110 451 93 54 147 760 245 1,005 KNUST 24 1 25 38 5 43 133 15 148 402 68 470 32 5 37 22 1 23 651 95 746 University of Cape Coast Univ. -

National Council for Tertiary Education Statistical Report on Tertiary Education for 2016/2017 Academic Year

NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR TERTIARY EDUCATION STATISTICAL REPORT ON TERTIARY EDUCATION FOR 2016/2017 ACADEMIC YEAR Research, Planning and Policy Development (RPPD) Department i Published by National Council for Tertiary Education P O Box MB 28 Accra © National Council for Tertiary Education 2018 Office Location Tertiary Education Complex Off the Trinity College Road Bawaleshie, East Legon Accra Tel: + 233 (0) 0209989429 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ncte.edu.gh ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES v LIST OF FIGURES vi LIST OF ACRONYMS viii INTRODUCTION 1 METHODOLOGY 2 1. SUMMARY OF ALL TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS 3 1.1 ENROLMENT 3 1.2 GROSS ENROLMENT RATIO (GER) 4 1.3 GENDER PARITY INDEX (GPI) 5 1.4 NUMBER OF STUDENTS IN TERTIARY EDUCATION PER 100,000 INHABITANTS 6 1.5 ENROLMENT IN SCIENCE AND ARTS RELATED PROGRAMMES 6 2. PUBLIC FUNDED UNIVERSITIES 7 2.1 ADMISSIONS INTO FULL-TIME (REGULAR) STUDY 7 2.2 FULL-TIME (REGULAR) STUDENTS’ ENROLMENT 8 2.3 FULL-TIME (REGULAR) POSTGRADUATE STUDENT ENROLMENT 9 2.4 FULL-TIME ENROLMENT IN SCIENCE AND ARTS RELATED PROGRAMMES 9 2.5 ENROLMENT OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS 10 2.6 FULL-TIME (REGULAR) ENROLMENT OF FEE-PAYING STUDENTS 11 2.7 FULL-TIME (TEACHING) ACADEMIC STAFF 11 2.8 STUDENT-TEACHER RATIO 12 2.9 GRADUATE OUTPUT 12 2.10 STUDENT ENROLMENTS IN DISTANCE AND SANDWICH PROGRAMMES 13 3. TECHNICAL UNIVERSITIES AND POLYTECHNICS 14 3.1 ADMISSIONS IN TECHNICAL UNIVERSITIES AND POLYTECHNICS 14 3.2 ENROLMENT IN THE TECHNICAL UNIVERSITIES AND POLYTECHNICS 14 3.3 STUDENT ENROLMENT IN SCIENCE AND ARTS RELATED PROGRAMMES 16 3.4 INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS 16 3.5 ACADEMIC STAFF 17 3.6 STUDENT-TEACHER RATIOS 17 3.7 GRADUATE OUTPUT 18 4. -

Volume 8/Number 1/ November 2020/Article 13

ANUJAT/VOLUME 8/NUMBER 1/ NOVEMBER 2020/ARTICLE 13 Volume 8/ Number 1 November 2020 Article 13 An Examination of Senior High Schools Teacher-Student Conflicts in Ghana GODWIN GYIMAH GODWIN GYIMAH holds Master of Arts in History from Eastern Illinois University, USA. He is a Graduate Assistant at Eastern Illinois University, U.S.A. NANA OSEI BONSU NANA OSEI BONSU holds a Bachelor of Education in History and Religion from the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. He is a history tutor at Aburaman Senior High School, Ghana. He is currently pursuing his Master of Education in Information Technology at the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. For this and additional works at: anujat.anuc.edu.gh Copyright © November 2020 All Nations University Journal of Applied Thought (ANUJAT) and Author Recommended Citation: Gyimah, G. & Bonsu, N. O. (2020). An Examination of Senior High Schools Teacher-Students’ Conflicts in Ghana. All Nations University Journal of Applied Though (ANUJAT),8(1): 186-198. All Nations University Press. doi: http://doi.org/10.47987/IRAY1926 Available at: http://anujat.anuc.edu.gh/universityjournal/anujat/Vol8/No1/13.pdf ANUJAT/VOLUME 8/NUMBER 1/ NOVEMBER 2020/ARTICLE 13 Research Online is the Institutional repository for All Nations University College. For further information, contact the ANUC Library: [email protected] Abstract This study sought to examine Senior High Schools Teacher-Student conflicts at Kwahu East Municipality, Ghana. The study adopted a descriptive research design. Data was collected through the use of questionnaires to a sample of 127 students. The findings revealed that some teachers unfair use of punishment, denial of students’ rights and privileges by teachers, lack of interest in teaching on the part of some teachers, and preferential treatment towards some students cause teacher-student conflicts. -

'The Art & Science of Fundraising'

‘The Art & Science of Fundraising’ A Study Visit to New York for Executives from African Universities and Cultural Institutions New York City Funded through the generous support of List of participants in the 2013 to 2019 study visit programs (Titles and affiliations as of year of participation) Prof. Otlogetswe Totolo, Vice-Chancellor, Botswana International University of Science & Technology, Botswana, 2016 Prof. Thabo Fako, Vice-Chancellor, University of Botswana, Botswana, 2013 Mr. Dawid B. Katzke, Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Finance & Administration, University of Botswana, Botswana, 2013 Dr. Baagi T. Mmereki, Director, University of Botswana Foundation, University of Botswana, Botswana, 2013 Ms. Pamela Khumbah, Director, Office of Advancement & Development, Catholic University Institute of Buea, Cameroon, 2016 Prof. Edward Oben Ako, Rector, University of Maroua, Cameroon, 2017 Ms. Djalita Fialho, Board Member, Pedro Pires Leadership Institute, Cape Verde, 2018 Amb. Honorat Emmanuel Koffi-Abeni, International Relations Advisor, MDE Business School (IHE-Afrique), Côte d'Ivoire, 2017 Mr. Didier Raux-Yao, Chief of Finance and Fundraising Officer, MDE Business School (IHE-Afrique), Côte d'Ivoire, 2017 Prof. Saliou Toure, President, International University of Grand-Bassam, Côte d'Ivoire, 2018 Mr. Samuel Koffi, Chief Operating Officer, International University of Grand-Bassam, Côte d'Ivoire, 2018 Ms. Ramatou Coulibaly-Gauze, Dir. of Admin. & Finance, International University of Grand-Bassam, Côte d'Ivoire, 2018 Prof. Léonard Santedi Kinkupu, Rector, Catholic University of Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2017 Dr. Ese Diejomaoh, Projects Coordinator, Centre Congolais de Culture de Formation et de Développement, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2016 Ms. Nicole Muyulu, Nurse Educator & Hygienist, Centre Congolais de Culture de Formation et de Développement, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2016 Mgr. -

Annette Froehlich ·André Siebrits Volume 1: a Primary Needs

Studies in Space Policy Annette Froehlich · André Siebrits Space Supporting Africa Volume 1: A Primary Needs Approach and Africa’s Emerging Space Middle Powers Studies in Space Policy Volume 20 Series Editor European Space Policy Institute, Vienna, Austria Editorial Advisory Board Genevieve Fioraso Gerd Gruppe Pavel Kabat Sergio Marchisio Dominique Tilmans Ene Ergma Ingolf Schädler Gilles Maquet Jaime Silva Edited by: European Space Policy Institute, Vienna, Austria Director: Jean-Jacques Tortora The use of outer space is of growing strategic and technological relevance. The development of robotic exploration to distant planets and bodies across the solar system, as well as pioneering human space exploration in earth orbit and of the moon, paved the way for ambitious long-term space exploration. Today, space exploration goes far beyond a merely technological endeavour, as its further development will have a tremendous social, cultural and economic impact. Space activities are entering an era in which contributions of the humanities—history, philosophy, anthropology—, the arts, and the social sciences—political science, economics, law—will become crucial for the future of space exploration. Space policy thus will gain in visibility and relevance. The series Studies in Space Policy shall become the European reference compilation edited by the leading institute in the field, the European Space Policy Institute. It will contain both monographs and collections dealing with their subjects in a transdisciplinary way. More information about this -

STRENGTHENING UNIVERSITY-INDUSTRY LINKAGES in AFRICA a Study on Institutional Capacities and Gaps

STRENGTHENING UNIVERSITY-INDUSTRY LINKAGES IN AFRICA A Study on Institutional Capacities and Gaps JOHN SSEBUWUFU, TERALYNN LUDWICK AND MARGAUX BÉLAND Funded by the Canadian Government through CIDA Canadian International Agence canadienne de Development Agency développement international STRENGTHENING UNIVERSITY-INDUSTRY LINKAGES IN AFRICA: A Study on Institutional Capacities and Gaps Prof. John Ssebuwufu Director, Research & Programmes Association of African Universities (AAU) Teralynn Ludwick Research Officer AAU Research and Programmes Department / AUCC Partnership Programmes Margaux Béland Director, Partnership Programmes Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada (AUCC) Currently on secondment to the Canadian Bureau for International Education (CBIE) Strengthening University-Industry Linkages in Africa: A Study of Institutional Capacities and Gaps @ 2012 Association of African Universities (AAU) All rights reserved Printed in Ghana Association of African Universities (AAU) 11 Aviation Road Extension P.O. Box 5744 Accra-North Ghana Tel: +233 (0) 302 774495/761588 Fax: +233 (0) 302 774821 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Web site: http://www.aau.org This study was undertaken by the Association of African Universities (AAU) and the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada (AUCC) as part of the project, Strengthening Higher Education Stakeholder Relations in Africa (SHESRA). The project is generously funded by Government of Canada through the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). The views and opinions -

ARDI Participating Academic Institutions

ARDI Participating Academic Institutions Filter Summary Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Charikar Parwan University Cheghcharan Ghor Institute of Higher Education Gardez Paktia University Ghazni Ghazni University Jalalabad Nangarhar University Kabul Social and Health Development Program (SHDP) Emergency NGO - Afghanistan French Medical Institute for children, FMIC American University of Afghanistan Kabul Polytechnic University Kateb University Afghan Evaluation Society Prof. Ghazanfar Institute of Health Sciences Information and Communication Technology Institute (ICTI) Kabul Medical University 19-Dec-2017 3:15 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 1 of 80 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Kabul Ministry of Public Health , Surveillance Department Kandahar Kandahar University Kapisa Alberoni University Lashkar Gah Helmand University Sheberghan Jawzjan university Albania Tirana Agricultural University of Tirana University of Tirana. Faculty of Natural Sciences Tirane, Albania Albanian Centre for Sustainable Development Algeria Alger Institut National Algerien de La Propriete Industrielle (INAPI) ouargla pépinière d'entreprises incubateur ouargla Tebessa Université Larbi Tébessi (University of Tebessa) 19-Dec-2017 3:15 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 2 of 80 Country City Institution Name Angola Luanda Instituto Superior Politécnico de Tecnologia e Ciências, ISPTEC Instituto oftalmológico nacional de Angola Instituto Nacional de Recursos Hídricos (INRH) Angolan Institute of Industrial Property MALANJE INSTITUTO SUPERIOR -

In Focus Activities

Vol. 16 N° 2 September 2010 www.iau-aiu.net IAU, founded in 1950, is the leading on common concerns. global association of higher IAU partners with UNESCO and education institutions and university other international, regional and associations. It has Member national bodies active in higher Institutions and Organisations from education. It is committed to some 130 countries that come building a worldwide higher together for reflection and action education community. ////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ACTIVITIES The IAU met in Vilnius, Lithuania last June IAU 3rd Global Survey Report on the Internationalisation of Higher Education Ongoing Projects Reports Upcoming Events IN FOCUS 10 years of Bologna in EuropE and in thE World CONTENTS WORD FROM THE SECRETARY GENERAL IAU NEwS and ActIvIties ‘InspiratIonal and AspiratIonal’ – these two adjectives are used in 1 1 IAU 2010 Board Meeting and Round Table the article by Obasi and Olutayo in this issue of IAU Horizons to describe the impact 3 IAU 2010 International Conference – Mykolas of the Bologna Process in Africa. Romeris University, Vilnius, Lithuania, 24-26 June 2010 – Conference highlights It seems that after 10 years of this continent-wide reform process, the same two 4 IAU and Internationalization: IAU 3rd Global words could be applied in Europe as well. As we witness the birth of the European Survey Report Published Higher Education Area, anchored firmly in the foundations laid down over the past 5 IAU Upcoming events: GMA IV; Kenya decade by Ministers, university and other higher education institution leaders, Conference; General Conference & students, faculty members and others, it is possible to applaud and rejoice about Sponsored events progress made, but to feel concern as well, especially when this process is imported 6 IAU reports on ongoing Projects and exported elsewhere. -

Hinari Participating Academic Institutions

Hinari Participating Academic Institutions Filter Summary Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Bamyan Bamyan University Chakcharan Ghor province regional hospital Charikar Parwan University Cheghcharan Ghor Institute of Higher Education Faizabad, Afghanistan Faizabad Provincial Hospital Ferozkoh Ghor university Gardez Paktia University Ghazni Ghazni University Ghor province Hazarajat community health project Herat Rizeuldin Research Institute And Medical Hospital HERAT UNIVERSITY 19-Dec-2017 3:13 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 1 of 367 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Herat Herat Institute of Health Sciences Herat Regional Military Hospital Herat Regional Hospital Health Clinic of Herat University Ghalib University Jalalabad Nangarhar University Alfalah University Kabul Kabul asia hospital Ministry of Higher Education Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) Afghanistan Public Health Institute, Ministry of Public Health Ministry of Public Health, Presidency of medical Jurisprudence Afghanistan National AIDS Control Program (A-NACP) Afghan Medical College Kabul JUNIPER MEDICAL AND DENTAL COLLEGE Government Medical College Kabul University. Faculty of Veterinary Science National Medical Library of Afghanistan Institute of Health Sciences Aga Khan University Programs in Afghanistan (AKU-PA) Health Services Support Project HMIS Health Management Information system 19-Dec-2017 3:13 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 2 of 367 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Kabul National Tuberculosis Program, Darulaman Salamati Health Messenger al-yusuf research institute Health Protection and Research Organisation (HPRO) Social and Health Development Program (SHDP) Afghan Society Against Cancer (ASAC) Kabul Dental College, Kabul Rabia Balkhi Hospital Cure International Hospital Mental Health Institute Emergency NGO - Afghanistan Al haj Prof. Mussa Wardak's hospital Afghan-COMET (Centre Of Multi-professional Education And Training) Wazir Akbar Khan Hospital French Medical Institute for children, FMIC Afghanistan Mercy Hospital. -

AFRICA NEWSLETTER the Geospatial Community July, 2013 Vol

SPATIAL DATA INFRASTRUCTURE - AFRICA NEWSLETTER The GeoSpatial Community July, 2013 Vol. 12, No. 7 SDI-Africa Newsletter The Spatial Data Infrastructure - Africa (SDI-Africa) is a free, electronic newsletter for people interested in Geographic Information System (GIS), remote sensing and data management in Africa. Published monthly since May 2002, it raises awareness and provide useful information to strengthen SDI efforts and support synchronization of To subscribe/unsubscribe to SDI-Africa or regional activities. The Newsletter is prepared for the GSDI Association by the change your email address, please do so Regional Centre for Mapping of Resources for Development online at: (RCMRD) in Nairobi, Kenya. http://www.gsdi.org/newslist/gsdisubscribe The Regional Centre for Mapping of Resources for Development (RCMRD) implements projects on behalf of its member States and development partners. The centre builds capacity in surveying and mapping, remote sensing, geographic information systems, and natural resources assessment and management. It has been active in SDI in Africa through contributions to the African Geodetic Reference Frame (AFREF) and SERVIR-Africa, a regional visualization and monitoring system initiative. Other regional groups promoting SDI in Africa are ECA/CODIST-Geo, RCMRD/SERVIR, RECTAS, AARSE, EIS-AFRICA, SDI-EA and MadMappers Announce your news or information Feel free to submit to us any news or information related to GIS, remote sensing, and spatial data infrastructure that you would like to highlight. Please send us websites, workshop/conference summary, events, research article or practical GIS/remote sesning application and implementation materials in your area, profession, organization or country. Kindly send them by the 25th of each month to the Editor, Gordon Ojwang’ - [email protected] or [email protected].