View / Open Final Thesis-Dicken J.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helena Chester the Discursive Construction of Freedom in The

The Discursive Construction of Freedom in the Watchtower Society Helena Chester Diploma of Teaching (Early Childhood): Riverina – Murray Institute of Higher Education Graduate Diploma of Education (Special Education): Victoria College. Master of Education (Honours): University of New England Thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Charles Darwin University, Darwin. October 2018 Certification I certify that the substance of this dissertation has not already been submitted for any degree and is not currently being submitted for any other degree or qualification. I certify that any help received in preparing this thesis, and all sources used, have been acknowledged in this thesis. Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 4 Dedication ............................................................................................................................. 5 Thesis Abstract ..................................................................................................................... 6 Keywords .............................................................................................................................. 7 Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................................ 8 Chapter 1: The Discursive Construction of Freedom in the Watchtower Society ................... 9 The Freedom Claim in the Watchtower Society ............................................................. -

QHN Spring 2020 Layout 1

WESTWARD HO! QHN FEATURES JOHN ABBOTT COLLEGE & MONTREAL’S WEST ISLAND $10 Quebec VOL 13, NO. 2 SPRING 2020 News “An Integral Part of the Community” John Abbot College celebrates seven decades Aviation, Arboretum, Islands and Canals Heritage Highlights along the West Island Shores Abbott’s Late Dean The Passing of a Memorable Mentor Quebec Editor’s desk 3 eritageNews H Vocation Spot Rod MacLeod EDITOR Who Are These Anglophones Anyway? 4 RODERICK MACLEOD An Address to the 10th Annual Arts, Matthew Farfan PRODUCTION Culture and Heritage Working Group DAN PINESE; MATTHEW FARFAN The West Island 5 PUBLISHER A Brief History Jim Hamilton QUEBEC ANGLOPHONE HERITAGE NETWORK John Abbott College 8 3355 COLLEGE 50 Years of Success Heather Darch SHERBROOKE, QUEBEC J1M 0B8 The Man from Argenteuil 11 PHONE The Life and Times of Sir John Abbott Jim Hamilton 1-877-964-0409 (819) 564-9595 A Symbol of Peace in 13 FAX (819) 564-6872 St. Anne de Bellevue Heather Darch CORRESPONDENCE [email protected] A Backyard Treasure 15 on the West Island Heather Darch WEBSITES QAHN.ORG QUEBECHERITAGEWEB.COM Boisbriand’s Legacy 16 100OBJECTS.QAHN.ORG A Brief History of Senneville Jim Hamilton PRESIDENT Angus Estate Heritage At Risk 17 GRANT MYERS Matthew Farfan EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR MATTHEW FARFAN Taking Flight on the West Island 18 PROJECT DIRECTORS Heather Darch DWANE WILKIN HEATHER DARCH Muskrats and Ruins on Dowker Island 20 CHRISTINA ADAMKO Heather Darch GLENN PATTERSON BOOKKEEPER Over the River and through the Woods 21 MARION GREENLAY to the Morgan Arboretum We Go! Heather Darch Quebec Heritage News is published quarterly by QAHN with the support Tiny Island’s Big History 22 of the Department of Canadian Heritage. -

Casemate Wall with Abutting Structures at Khirbet Qeiyafa: the Archaeology of Architecture and Its Implications for Khirbet Qeiyafa’S Identity

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! The Architectural Phenomenon of ‘Casemate Wall with Abutting Structures at Khirbet Qeiyafa: The archaeology of Architecture and its Implications for Khirbet Qeiyafa’s Identity Rachel Hyung Guong Ko School of Religious Studies McGill University, Montreal February 2018 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts (M.A. thesis). ©2018 by Rachel Hyung Guong Ko ABSTRACT This work catalogues and re-examines the main architectural features that were uncovered at the Iron Age city of Khirbet Qeiyafa. The site was excavated for a total of seven seasons under the direction of Dr. Yosef Garfinkel of the Hebrew University and Saar Ganor on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authorities; Michael G. Hasel of the Southern Adventist University joined Garfinkel and Ganor for the 2009-2011 excavation seasons. The excavators have proposed that the site be identified as the biblical site of Sha’arayim, meaning “two gates”, mentioned three times in the Hebrew Bible (Joshua 15:36, 1 Samuel 17:52, 1 Chronicles 4: 31). Their identification of Khirbet Qeiyafa as belonging to the kingdom of Judah has stirred much controversy amongst scholars who support current theories of state formation in the Levant during the Iron Age. These scholars, so called ‘minimalists’, maintain that there is no archaeological evidence to support an United Monarchy, and insist that the northern Kingdom of Israel only emerged in the early 9th century BC, and the kingdom of Judah only in the late 8th century BCE, some 300 years later than the events as purported to have happened in the biblical narrative (Lemche 1988; Finkelstein 1996; Thompson 1999)”.1 The architectural remains of the Iron Age city at Khirbet Qeiyafa have been particularly important in the discussion regarding the socio-political identity and the territorial affiliation of the site. -

Tanakh and Archaeology B. from Achav Onwards the Latest

Fundamental Issues in the Study of Tanakh By Rav Amnon Bazak Shiur #6b: Tanakh and Archaeology B. From Achav onwards The latest period in which controversy arises regarding the relationship between the Biblical text and the archaeological record is from the reign of King Achav, in the first half of the 9th century B.C.E., onwards.[1] Archaeological discoveries dating from this time – which many researchers believe to be the period during which the Books of the Torah and of the Prophets were written – do generally accord with the textual account, and therefore scholars acknowledge the basic reliability of the Tanakh’s historical descriptions from this period onwards. These discoveries are very exciting in their own right, lending a powerful sense of connection to the world of the Tanakh through a direct, unmediated encounter with the remains of the concrete reality described in the text. Indeed, the discovery of the first relevant findings, in the 19th century, refuted some prevalent critical approaches which had maintained that all the biblical narratives were later creations, severed from any historical context. We shall discuss some of the most famous findings relating to narratives about the Israelite kingdom from the period of Achav onwards. 1. In Sefer Melakhim we read: "And Mesha, king of Moav, was a sheepmaster, and he delivered to the king of Israel a hundred thousand lambs, and a hundred thousand rams, with the wool. But it was, when Achav died, that the king of Moav rebelled against the king of Israel…" (Melakhim II 3:4-5) In 1868, a stele (inscribed stone) dating to the 9th century B.C.E. -

Record of Protected Structures

RECORD OF PROTECTED STRUCTURES Glenties Electoral Area Ref. Name Description Address Number Electoral Area Rating Importance Value 40904202 Dunlewey House Detached early 19th century three-bay two-storey house with projecting open Dunlewey House, Glenties E.A. Regional AGSM porch, recessed two-storey wing to east, three-bay single-storey battlemented Dunlewey, Gweedore billiard room to west, two-storey wing to south, with two-and single-storey canted bay windows to west. 40902615 St John's Church Detached four-bay single-storey Church of Ireland Church, built 1752, with bell St. John's, Clondehorky Glenties E.A. National AIPSM cote to west gable Venetian east window, internal gallery, porch with staircase Parish, Ballymore to west and projecting gabled vestry to north-west corner. Lower, Creeslough 40903210 Carrickfin Church Detached three-bay single-storey Church of Ireland Chapel of Ease with gabled Carrickfin Church, Glenties E.A. Regional AHSM entrance porch, with bellcote to centre of south-west side and projecting sacristy Carrickfin, Kincasslagh, to north, built early 19th century. Letterkenny 40902601 St Michaels Church Detached Ronchamp-esque Catholic Church built 1970, with Baptistry, Blessed Creeslough Glenties E.A. National AP Sacrament Chapel, entrance porch, sacristy, confessionals and Marian chapel to perimeter. 40901501 Hornhead Bridge Twelve arch rubble stone road bridge over tidal stream built c.1800 with rubble Dunfanaghy Glenties E.A. Regional ATS stone segment arches; vaults, cutwaters, parapets, abutments and causeway to south. 40905802 Doocharry Bridge Road bridge over Gweebara river in two segmental-arched spans with custone Doocharry Bridge, Glenties E.A. Regional ATS voussoirs, dressed squared rubble stone haunched ashlar abutments and rubble Doochary stone parapets. -

Traces of the Past Along the German Green Belt

The Green Belt in its entire length is not a well developed and signposted hike and bicycle path. It is not always easy to tell where the former border strip was, as most of the border fortifications have been dismantled. Moreover, in some places the Green Belt is not recognisable because parts of it are now used as intensive grassland, arable land Traces of the Past or woodland. along the German Green Belt “Those who cannot remember their past are condemned to repeat it.” (George Santayana) The Green Belt in its entire length is not a well developed and signposted hike and bicycle path. It is not always easy to tell where the former border strip was, as most of the border fortifications have been dismantled. Moreover, in some places the Green Belt is not recognisable because parts of it are now used as intensive grassland, arable land or woodland. East German border guard on patrol Opening of the border at Mödlareuth “Western tourists” at the Iron Curtain 2 INHALT FOREWORD Dear visitors of the Green Belt and the borderland museums, For more than 25 years, the Green Belt, the stretch of unspoilt nature that has arisen as a result of the inhumane inner-German border, has been a constant reminder of our once divided nation. Nature has been left to its own devices here, not because we want to forget, but because we want to remember. Scores of people visit the Green Belt in an attempt to come to terms with history: the history of their country, their mothers and fathers, relatives, friends or even their own personal fate. -

Val-Des-Arbres Citizens Demand Removal of Bike Path... PAGE 5

Introducing, Mediterranean taste at your home our new Pilaros Pita! Also available in pie format TAKE OUT & DELIVERY Wednesday-Thursday Friday-Saturday 3pm - 8pm 3pm- 9pm 1670 Saint-Martin West 4806 Park Ave. It’s not a trend, it’s a tradition! 579-640-9099 514 271-9099 www.pilaros.com [email protected] • www.philinos.ca 1.888.PILAROS • 450.681.6900 Laval’s English Paper, Since 1993 Vol. 28 - No. 12 June 10, 2020 450-978-9999 www.lavalnews.ca [email protected] 120,000 readers Val-des-Arbres citizens Let’s continue to protect ourselves and consult demand removal health professionals! of bike path... PAGE 5 Information and advice inside. 20-210-192FA_Formats-promo_EN_.indd 2 20-06-03 09:59 MATURE L I F E Costas Rodaros shows a petition with more than 65 signatures he RAYMONDE FOLCO: helped to gather on de Blois Blvd. TEACHER, in Val-des-Arbres, calling for the PARLIAMENTARIAN, elimination of a bike path in front INSPIRATIONAL of their homes. Photo: Martin C. Barry WOMAN OF POWER AND INFLUENCE June 10, 2020 • nd BREAKING NEWS: Starting June 22 , small indoor gatherings and dining in restaurants The Laval News • will be allowed, with certain restrictions everywhere. Details at lavalnews.ca Pages 11-22 11 Happy Father’s Day to all the fathers of Chomedey ! & a Happy St-Jean-Baptiste Day to all ! Guy Ouellette 450 686-0166 | [email protected] MNA for Chomedey 4599, boul. Samson, Bureau 201, Laval (QC) H7W 2H2 Even during a pandemic, you can consult a professional. -

Bickleigh Castle an English Historical Landmark

Bickleigh Castle An English Historical Landmark Gardens, Guided Tour & Tea Room OPEN APRIL TO OCTOBER Walk in the footsteps of the English Monarchy! Bickleigh Castle, Tiverton, Devon, EX16 8RP www.bickleighcastle.com Bickleigh Castle An English Historical Landmark Bickleigh Castle originates in Saxon times when there was the fortified village of Bickleigh on the site, with a stone wall and watchtower. The Castle itself was built in the early Norman period, remodelled and enlarged as a fortified Manor House in the 1400s, damaged badly in the English Civil War, and restored in the 18th, 19th & 20th Centuries. A FASCINATING HISTORY The Castle has a fascinating history, with many interesting, famous and even infamous characters in its past and has particularly close links to the medieval monarchy, the Tudors and the Stuarts. Come and hear about the various Royal visitors, the families de Redvers, Courtenay and Carew, and see the armour and artefacts and some fine 17th Century portraits, several of kings and other royalty. AFTERNOON TEA & GARDENS Follow your tour of the Castle with a delicious Afternoon Tea in our Orangery. You are also most welcome to take a walk round our gardens. “1080s Bickleigh Castle was listed in the Domesday Book (1086) and the lands of some 3000 acres subsequently granted to Sir Richard de Redvers by King William I. A substantial Norman fortress was built, which included an inner and outer keep, moat and castellations.” OPENING TIMES Thursdays Only 4th April - 31st Ocotber Gardens Open 12.00pm - 5.30pm Castle Guided Tour 1.00pm and 3.00pm Tea Room Open 12.00pm - 5.00pm Serving cream teas, cakes and light refreshements PRICES Gardens & Grounds Only Adults ................................................................................... -

From to Here Here

From here To here BIBLICAL SURVEY: Old Testament The Divided Monarchy: Judah (Part 3) Biblical-Literacy.com © Copyright 2011 by Mark Lanier. Permission hereby granted to reprint this document in its entirety without change, with reference given, and not for financial profit. 1040 Saul 1040 1010 Saul David 1040 1010 970 Saul David Solomon 1040 1010 970 930 Jeroboam (22 yrs) Saul David Solomon Rehoboam (17 yrs) 930 Jeroboam (22 yrs) Rehoboam (17 yrs) Jeroboam (22 yrs) 930 Rehoboam (17 yrs) Jeroboam (22 yrs) 930 Rehoboam (17 yrs) Invasion of Pharaoh Shoshenq I Nadab (2 yrs) Jeroboam (22 yrs) 930 Rehoboam (17 yrs) Invasion of Pharaoh Shoshenq I Nadab (2 yrs) Jeroboam Baasha (24 yrs) (22 yrs) 930 Rehoboam (17 yrs) Invasion of Pharaoh Shoshenq I Nadab (2 yrs) Jeroboam Baasha (24 yrs) (22 yrs) Elah/Zimri/Omri (2 yrs/7 days/12 yrs) 930 Rehoboam (17 yrs) Invasion of Pharaoh Shoshenq I Nadab (2 yrs) Jeroboam Baasha (24 yrs) (22 yrs) Elah/Zimri/Omri (2 yrs/7 days/12 yrs) 930 880 Rehoboam (17 yrs) Invasion of Pharaoh Shoshenq I Nadab (2 yrs) Ahab/Jezebel Jeroboam Baasha (24 yrs) (22 yrs) Elah/Zimri/Omri (2 yrs/7 days/12 yrs) 930 880 Rehoboam (17 yrs) Invasion of Pharaoh Shoshenq I Nadab (2 yrs) Ahab/Jezebel Jeroboam Baasha (24 yrs) (22 yrs) Elah/Zimri/Omri (2 yrs/7 days/12 yrs) 930 880 Rehoboam (17 yrs) Abijam (2 yrs) Invasion of Pharaoh Shoshenq I Nadab (2 yrs) Ahab/Jezebel Jeroboam Baasha (24 yrs) (22 yrs) Elah/Zimri/Omri (2 yrs/7 days/12 yrs) 930 880 Rehoboam (17 yrs) Abijam (2 yrs) Asa (41 yrs) Invasion of Pharaoh Shoshenq I Nadab (2 yrs) Ahab/Jezebel -

Hadrian's Wall 1999-2009

HADRIAN’S WALL 1999-2009 HADRIAN’S WALL HADRIAN’S WALL 1999-2009 A summary of recent excavation and research prepared for the Thirteenth Pilgrimage of Hadrian’s Wall, 2009 HADRIAN’S WALL 1999-2009 The Pilgrimage of Hadrian’s Wall (a tradition going back to 1849) takes place every ten years, giving all who are interested in the remains of Rome’s most elaborate frontier a chance to revisit the remains and hear about the latest archaeological developments. This specially prepared book, with contributions from all the major excavators on the Wall, describes research and discovery that has taken place since the last pilgrimage in 1999. This has been an extraordinary decade for Wall-research, featuring the discovery of the probable ancient name for the barrier, and the recognition Compiled by N. Hodgson of a previously unknown element of its anatomy (obstacles in front of the Wall), which is the rst such addition to our image of the Wall in modern times. This book explains where the new information is to be found, and will appeal to all who visit or study Hadrian’s remarkable frontier. CUMBERLAND & WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE Compiled by N. Hodgson Front cover: the Staffordshire Moorlands Pan, inscribed with the names of Wall- forts and the probable ancient name of the Wall (courtesy of Portable Antiquities Scheme) Back cover: emplacements for obstacles between the Wall and its ditch, under excavation at Byker, Newcastle upon Tyne 551114_TWM_COVER.indd1114_TWM_COVER.indd 1 117/07/20097/07/2009 009:319:31 CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE HADRIAN’S WALL 1999-2009 A Summary of Excavation and Research prepared for The Thirteenth Pilgrimage of Hadrian’s Wall, 8-14 August 2009 compiled by N. -

07.Tunez.Recorrido Vii

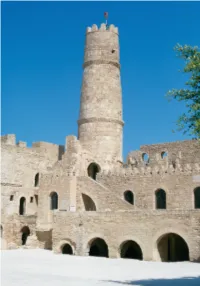

ITINERARY VII The Ribat Towns Mourad Rammah VII.1 MONASTIR VII.1.a The Ribat VII.1.b Sidi al-Ghedamsi Ribat (option) VII.2 LEMTA VII.2.a The Ribat (option) VII.3 SOUSSE VII.3.a The Ribat VII.3.b The Great Mosque VII.3.c Al-Zaqqaq Madrasa VII.3.d Qubba bin al-Qhawi VII.3.e Sidi ‘Ali ‘Ammar Mosque VII.3.f Buftata Mosque VII.3.g The Kasbah and the Ramparts The Ribat, Monastir. 185 ITINERARY VII The Ribat Towns Monastir The assaults of the Byzantine fleet along the itary and religious purpose were reflected coast following the Muslim Conquest in their robust and austere architecture, forced the Ifriqiyans to build a continuous characterised by the use of stone and vaults line of defence consisting of fortresses made of rubble and the banishment of called ribats. They rose along the coastline wood coverings and light structures. This from Tangier to Alexandria and communi- type of architecture spread across the cated via the use of fires lit up at the top of whole of the Tunisian Sahel, and Sousse and the towers. The ribats served as a refuge for Monastir became the two ribat-towns par the inhabitants of the surrounding coun- excellence. tryside and were lived in by warrior Whilst all making reference to the same monks. The prolonged stays and visits of school of architecture, they nevertheless the most illustrious Ifriqiyan scholars, each underwent a slightly different evolu- jurisconsults and ascetics reinforced the tion. Sousse became in the 3rd/9th century spiritual prestige of these buildings, trans- the headquarters of the Aghlabid fleet and forming them into veritable monastery- the most important naval military base, fortresses and centres of learning that which was involved in the Conquest of Sici- transmitted Arab-Muslim culture along the ly in 211/827, as well as being the crucible north coast of North Africa. -

Developing Archaeological Audiences Along the Roman Route Aquileia

Developing archaeological audiences along the Roman route Aquileia-Emona-Sirmium-Viminacium Ljubljana, July 2016 WP3, Task 3.1 – Historiographic research update on the Roman route Index 3 Bernarda Županek, Musem and Galleries of Ljubljana Roman road Aquileia-Emona- Siscia-Sirmium-Viminacium: the Slovenian section 21 Dora Kušan Špalj and Nikoleta Perok, Archaeological Museum in Zagreb Roman road Aquileia-Emona-Siscia-Viminacium: Section of the road in the territory of present-day Croatia 37 Biljana Lučić, Institute for protection of cultural monuments Sremska Mitrovica Contribution to the research of the main Roman road through Srem 45 Ilija Danković and Nemanja Mrđić, Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade From Singidunum to Viminacium through Moesia Superior 2 Bernarda Županek, Musem and Galleries of Ljubljana Roman road Aquileia-Emona- Siscia-Sirmium-Viminacium: the Slovenian section The construction of the road that connected the Italic region with central Slovenia, and then made its way towards the east, was of key strategic importance for the Roman conquest of regions between the Sava and the Danube at the end of the first century BC. After the administrative establishment of the province of Pannonia this road became the main communication route, in the west-east direction, between Italy and the eastern provinces, especially with Pannonia and Moesia. The start of the road, which we follow in the context of the ARCHEST project, was in Aquileia, then across Emona to Neviodunim, passing Aquae Iassae towards Siscia and onwards into Sirmium, Singidunum and Viminacium. Myth-shrouded beginnings: the Amber Road and the Argonauts The territory of modern Slovenia was already covered with various routes during prehistoric times.