07.Tunez.Recorrido Vii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helena Chester the Discursive Construction of Freedom in The

The Discursive Construction of Freedom in the Watchtower Society Helena Chester Diploma of Teaching (Early Childhood): Riverina – Murray Institute of Higher Education Graduate Diploma of Education (Special Education): Victoria College. Master of Education (Honours): University of New England Thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Charles Darwin University, Darwin. October 2018 Certification I certify that the substance of this dissertation has not already been submitted for any degree and is not currently being submitted for any other degree or qualification. I certify that any help received in preparing this thesis, and all sources used, have been acknowledged in this thesis. Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 4 Dedication ............................................................................................................................. 5 Thesis Abstract ..................................................................................................................... 6 Keywords .............................................................................................................................. 7 Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................................ 8 Chapter 1: The Discursive Construction of Freedom in the Watchtower Society ................... 9 The Freedom Claim in the Watchtower Society ............................................................. -

PDF. Ksar Seghir 2500Ans D'échanges Inter-Civilisationnels En

Ksar Seghir 2500 ans d’échanges intercivilisationnels en Méditerranée • Première Edition : Institut des Etudes Hispanos-Lusophones. 2012 • Coordination éditoriale : Fatiha BENLABBAH et Abdelatif EL BOUDJAY • I.S.B.N : 978-9954-22-922-4 • Dépôt Légal: 2012 MO 1598 Tous droits réservés Sommaire SOMMAIRE • Préfaces 5 • Présentation 9 • Abdelaziz EL KHAYARI , Aomar AKERRAZ 11 Nouvelles données archéologiques sur l’occupation de la basse vallée de Ksar de la période tardo-antique au haut Moyen-âge • Tarik MOUJOUD 35 Ksar-Seghir d’après les sources médiévales d’histoire et de géographie • Patrice CRESSIER 61 Al-Qasr al-Saghîr, ville ronde • Jorge CORREIA 91 Ksar Seghir : Apports sur l’état de l’art et révisoin critique • Abdelatif ELBOUDJAY 107 La mise en valeur du site archéologique de Ksar Seghir Bilan et perspectives 155 عبد الهادي التازي • مدينة الق�رص ال�صغري من خﻻل التاريخ الدويل للمغرب Préfaces PREFACES e patrimoine archéologique marocain, outre qu’il contribue à mieux Lconnaître l’histoire de notre pays, il est aussi une source inépuisable et porteuse de richesse et un outil de développement par excellence. A travers le territoire du Maroc s’éparpillent une multitude de sites archéologiques allant du mineur au majeur. Citons entre autres les célèbres grottes préhistoriques de Casablanca, le singulier cromlech de Mzora, les villes antiques de Volubilis, de Lixus, de Banasa, de Tamuda et de Zilil, les sites archéologies médiévaux de Basra, Sijilmassa, Ghassasa, Mazemma, Aghmat, Tamdoult et Ksar Seghir objet de cet important colloque. Le site archéologique de Ksar Seghir est fameux par son évolution historique, par sa situation géographique et par son urbanisme particulier. -

View / Download 7.3 Mb

Between Shanghai and Mecca: Diaspora and Diplomacy of Chinese Muslims in the Twentieth Century by Janice Hyeju Jeong Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Advisor ___________________________ Prasenjit Duara, Advisor ___________________________ Nicole Barnes ___________________________ Adam Mestyan ___________________________ Cemil Aydin Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT Between Shanghai and Mecca: Diaspora and Diplomacy of Chinese Muslims in the Twentieth Century by Janice Hyeju Jeong Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Advisor ___________________________ Prasenjit Duara, Advisor ___________________________ Nicole Barnes ___________________________ Adam Mestyan ___________________________ Cemil Aydin An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by Janice Hyeju Jeong 2019 Abstract While China’s recent Belt and the Road Initiative and its expansion across Eurasia is garnering public and scholarly attention, this dissertation recasts the space of Eurasia as one connected through historic Islamic networks between Mecca and China. Specifically, I show that eruptions of -

Tradition and Sustainability in Vernacular Architecture of Southeast Morocco

sustainability Article Tradition and Sustainability in Vernacular Architecture of Southeast Morocco Teresa Gil-Piqueras * and Pablo Rodríguez-Navarro Centro de Investigación en Arquitectura, Patrimonio y Gestión para el Desarrollo Sostenible–PEGASO, Universitat Politècnica de València, Cno. de Vera, s/n, 46022 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This article is presented after ten years of research on the earthen architecture of southeast- ern Morocco, more specifically that of the natural axis connecting the cities of Midelt and Er-Rachidia, located North and South of the Moroccan northern High Atlas. The typology studied is called ksar (ksour, pl.). Throughout various research projects, we have been able to explore this territory, documenting in field sheets the characteristics of a total of 30 ksour in the Outat valley, 20 in the mountain range and 53 in the Mdagra oasis. The objective of the present work is to analyze, through qualitative and quantitative data, the main characteristics of this vernacular architecture as a perfect example of an environmentally respectful habitat, obtaining concrete data on its traditional character and its sustainability. The methodology followed is based on case studies and, as a result, we have obtained a typological classification of the ksour of this region and their relationship with the territory, as well as the social, functional, defensive, productive, and building characteristics that define them. Knowing and puttin in value this vernacular heritage is the first step towards protecting it and to show our commitment to future generations. Keywords: ksar; vernacular architecture; rammed earth; Morocco; typologies; oasis; High Atlas; sustainable traditional architecture Citation: Gil-Piqueras, T.; Rodríguez-Navarro, P. -

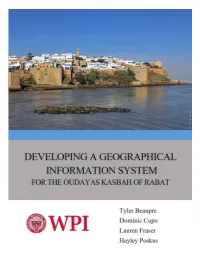

Developing a Geographical Information System for the Oudayas Kasbah of Rabat

Developing a Geographical Information System for the Oudayas Kasbah of Rabat An Interactive Qualifying Project (IQP) Proposal submitted to the faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelors of Science in cooperation with The Prefecture of Rabat Submitted by: Project Advisors: Tyler Beaupre Professor Ingrid Shockey Dominic Cupo Professor Gbetonmasse Somasse Lauren Fraser Hayley Poskus Submitted to: Mr. Hammadi Houra, Sponsor Liaison Submitted on October 12th, 2016 ABSTRACT An accurate map of a city is essential for supplementing tourist traffic and management by the local government. The city of Rabat was lacking such a map for the Kasbah of the Oudayas. With the assistance of the Prefecture of Rabat, we created a Geographical Information System (GIS) for that section of the medina using QGIS software. Within this GIS, we mapped the area, added historical landmarks and tourist attractions, and created a walking tour of the Oudayas Kasbah. This prototype remains expandable, allowing the prefecture to extend the system to all the city of Rabat. i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction In 2012, the city of Rabat, Morocco was awarded the status of a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) world heritage site for integrating both Western Modernism and Arabo-Muslim history, creating a unique juxtaposition of cultures (UNESCO, 2016). The Kasbah of the Oudayas, a twelfth century fortress in the city, exemplifies this connection. A view of the Bab Oudaya is shown below in Figure 1. It is a popular tourist attraction and has assisted Rabat in bringing in an average of 500,000 tourists per year (World Bank, 2016). -

A Note from Sir Richard Branson

A NOTE FROM SIR RICHARD BRANSON “ In 1998, I went to Morocco with the goal of circumnavigating the globe in a hot air balloon. Whilst there, my parents found a beautiful Kasbah and dreamed of turning it into a wonderful Moroccan retreat. Sadly, I didn’t quite manage to realise my goal on that occasion, however I did purchase that magnificent Kasbah and now my parents’ dream has become a reality. I am pleased to welcome you to Kasbah Tamadot, (Tamadot meaning soft breeze in Berber), which is perhaps one of the most beautiful properties in the high Atlas Mountains of Morocco. I hope you enjoy this magical place; I’m sure you too will fall in love with it.” Sir Richard Branson 2- 5 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW 14 Babouches ACTIVITIES AT KASBAH Babysitting TAMADOT Cash and credit cards Stargazing Cigars Trekking in the Atlas Mountains Departure Asni Market Tours WELCOME TO KASBAH TAMADOT Do not disturb Cooking classes Fire evacuation routes Welcome to Kasbah Tamadot (pronounced: tam-a-dot)! Four legged friends We’re delighted you’ve come to stay with us. Games, DVDs and CDs This magical place is perfect for rest and relaxation; you can Kasbah Tamadot Gift Shop 1 5 do as much or as little as you like. Enjoy the fresh mountain air The Berber Boutique KASBAH KIDS as you wander around our beautiful gardens of specimen fruit Laundry and dry cleaning Activities for children trees and rambling rose bushes, or go on a trek through the Lost or found something? Medical assistance and pharmacy High Atlas Mountains...the choice is yours. -

Amerikiečiai Bombarduoja Bizerte

4 Ii: As \-į** 4• • it- yį*4.»**-.--^r>.i'WJ-***** -«•"•»«<*•^-•»«* - $•*•*•«•• »- 4.* ^ »7į,y,w4u*^ **w- %-»- -v-.«V••h-«^-V^.*--I**V«V *#"«•#*» •»*«•t "»*** »»*»"*»»-*r ^--ty * *•»,--•*./*W-%- V * *••«**<«*•>-.,v.Wy. *.#v#-*.#S# •.*• -.'^- »»A * M» -V W •>**>< r ••' ,**>* . • w,, -, ., .- *»> -• V •• •••-•'•'-• X ••••,-«:.. • ,-.•. /»•»• f»• ..- •- - ,•' .4- - ,. •:« ~*¥ x*$?7 >k r">:> « v v ^y®fyrv®tr<ftvS ^ "-\) ^ <' i w ^ ^ i . ,,-H f •» _ "*» . '* ^ - ' •*, , * V 't? ^ ',-« * fj \ : f, ** • t*- •*,.!. -r •> -J , - 7 J v 't* > ^ r <" • -««• . h ' ' t >« 1 f ** >'rf1 , tJ* * * ,.. •v*-* , ' * - ' < "' " " x :v> ^ tA% ^ s$įt ^ V , /', Jt -v-'V -i.i;'.. % '-/ '^; ' «;J( . •rK «-s W- 4 , Wr^t / , ± r » **\ . j./r si ^ į JW"l I I 'I' wi'li.i hI ' - T -n s,... DIRVA (THE FIELD). DIRVA (THE FIELD)* . LITHUANIAN WEEKLY .4 V SAVAITINIS LAIKUASTlg » 'į* Published every Friday in Cleveland bu tte Vi?' "*". Ohio Lithuanian Publishing Co. ' U leidžia Penktadieniais Cleveland# M20 Superior Ave. Cleveland, Ohio Ohio Lietuvių Spaudos Bendro*! -< i.? % Subscription per Year in Advance Metini Prenumerata In the United States $2.00 Suvienytose Valstijose $2X0 In Canada $2.5C| Kanadoje (2.90 j Entered as Second-Class matter Decent ber 6th, 1915, at the Cleveland Postoffic® 0 t R VA ^ under the Act of March 3, 1879. The only Iv aonal Lithuanian Newspaper published in Ohio, reaching a very large majority of the 6820 Superior Ave. Cleveland. Ohio II] jimmmmm i i 80,000 Lithuanians in the State and 20,000 in Cleveland No. 19 KAINA 5c. CLEVELAND. OHIO GEGUŽĖS-MAY -

QHN Spring 2020 Layout 1

WESTWARD HO! QHN FEATURES JOHN ABBOTT COLLEGE & MONTREAL’S WEST ISLAND $10 Quebec VOL 13, NO. 2 SPRING 2020 News “An Integral Part of the Community” John Abbot College celebrates seven decades Aviation, Arboretum, Islands and Canals Heritage Highlights along the West Island Shores Abbott’s Late Dean The Passing of a Memorable Mentor Quebec Editor’s desk 3 eritageNews H Vocation Spot Rod MacLeod EDITOR Who Are These Anglophones Anyway? 4 RODERICK MACLEOD An Address to the 10th Annual Arts, Matthew Farfan PRODUCTION Culture and Heritage Working Group DAN PINESE; MATTHEW FARFAN The West Island 5 PUBLISHER A Brief History Jim Hamilton QUEBEC ANGLOPHONE HERITAGE NETWORK John Abbott College 8 3355 COLLEGE 50 Years of Success Heather Darch SHERBROOKE, QUEBEC J1M 0B8 The Man from Argenteuil 11 PHONE The Life and Times of Sir John Abbott Jim Hamilton 1-877-964-0409 (819) 564-9595 A Symbol of Peace in 13 FAX (819) 564-6872 St. Anne de Bellevue Heather Darch CORRESPONDENCE [email protected] A Backyard Treasure 15 on the West Island Heather Darch WEBSITES QAHN.ORG QUEBECHERITAGEWEB.COM Boisbriand’s Legacy 16 100OBJECTS.QAHN.ORG A Brief History of Senneville Jim Hamilton PRESIDENT Angus Estate Heritage At Risk 17 GRANT MYERS Matthew Farfan EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR MATTHEW FARFAN Taking Flight on the West Island 18 PROJECT DIRECTORS Heather Darch DWANE WILKIN HEATHER DARCH Muskrats and Ruins on Dowker Island 20 CHRISTINA ADAMKO Heather Darch GLENN PATTERSON BOOKKEEPER Over the River and through the Woods 21 MARION GREENLAY to the Morgan Arboretum We Go! Heather Darch Quebec Heritage News is published quarterly by QAHN with the support Tiny Island’s Big History 22 of the Department of Canadian Heritage. -

1 Settlement Patterns in Roman Galicia

Settlement Patterns in Roman Galicia: Late Iron Age – Second Century AD Jonathan Wynne Rees Thesis submitted in requirement of fulfilments for the degree of Ph.D. in Archaeology, at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London University of London 2012 1 I, Jonathan Wynne Rees confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis examines the changes which occurred in the cultural landscapes of northwest Iberia, between the end of the Iron Age and the consolidation of the region by both the native elite and imperial authorities during the early Roman empire. As a means to analyse the impact of Roman power on the native peoples of northwest Iberia five study areas in northern Portugal were chosen, which stretch from the mountainous region of Trás-os-Montes near the modern-day Spanish border, moving west to the Tâmega Valley and the Atlantic coastal area. The divergent physical environments, different social practices and political affinities which these diverse regions offer, coupled with differing levels of contact with the Roman world, form the basis for a comparative examination of the area. In seeking to analyse the transformations which took place between the Late pre-Roman Iron Age and the early Roman period historical, archaeological and anthropological approaches from within Iberian academia and beyond were analysed. From these debates, three key questions were formulated, focusing on -

Reasonable Plans. the Story of the Kasbah Du Toubkal

The Story of the Kasbah du Toubkal MARRAKECH • MOROCCO DEREK WORKMAN The Story of the Kasbah du Toubkal Marrakech • Morocco Derek WorkMan Second edition (2014) The information in this booklet can be used copyright free (without editorial changes) with a credit given to the Kasbah du Toubkal and/or Discover Ltd. For permission to make editorial changes please contact the Kasbah du Toubkal at [email protected], or tel. +44 (0)1883 744 392. Discover Ltd, Timbers, Oxted Road, Godstone, Surrey, RH9 8AD Photography: Alan Keohane, Derek Workman, Bonnie Riehl and others Book design/layout: Alison Rayner We are pleased to be a founding member of the prestigious National Geographic network Dedication Dreams are only the plans of the reasonable – dreamt by Discover realised by Omar and the Worker of Imlil (Inscription on a brass plaque at the entrance to the Kasbah du Toubkal) his booklet is dedicated to the people of Imlil, and to all those who Thelped bring the ‘reasonable plans’ to reality, whether through direct involvement with Discover Ltd. and the Kasbah du Toubkal, or by simply offering what they could along the way. Long may they continue to do so. And of course to all our guests who contribute through the five percent levy that makes our work in the community possible. CONTENTS IntroDuctIon .........................................................................................7 CHAPTER 1 • The House on the Hill .......................................13 CHAPTER 2 • Taking Care of Business .................................29 CHAPTER 3 • one hand clapping .............................................47 CHAPTER 4 • An Association of Ideas ...................................57 CHAPTER 5 • The Work of Education For All ....................77 CHAPTER 6 • By Bike Through the High Atlas Mountains .......................................99 CHAPTER 7 • So Where Do We Go From Here? .......... -

The History and Description of Africa and of the Notable Things Therein Contained, Vol

The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained, Vol. 3 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.CH.DOCUMENT.nuhmafricanus3 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained, Vol. 3 Alternative title The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained Author/Creator Leo Africanus Contributor Pory, John (tr.), Brown, Robert (ed.) Date 1896 Resource type Books Language English, Italian Subject Coverage (spatial) Northern Swahili Coast;Middle Niger, Mali, Timbucktu, Southern Swahili Coast Source Northwestern University Libraries, G161 .H2 Description Written by al-Hassan ibn-Mohammed al-Wezaz al-Fasi, a Muslim, baptised as Giovanni Leone, but better known as Leo Africanus. -

An Architectural Heritage with Strong Islamic Influence

Fernando Branco Correia, Int. J. of Herit. Archit., Vol. 1, No. 4 (2017) 640–653 SOUTHERN PORTUGAL – AN ARCHITECTURAL HERitaGE WITH STRONG ISLAMIC INFLUENCE FERnando BRANCO CORREIA CIDEHUS – Universidade de Évora, Portugal. ABSTRACT The western part of al-Andalus was a peripheral zone of the Islamic World, far from the area of the Gua- dalquivir River and the Mediterranean coast. But in this western area there are important architectural elements from the Islamic era. In addition to the reuse of defensive and civilian structures from Roman times, there were military building programmes on the coastlines, from the 9th century onwards, with the arrival of Norse raiders. Moreover, some chronicles refer, for the 10th and 11th centuries, to the con- struction of ‘qasaba’(s) (military enclosures) in some cities and the total reconstruction of city walls. Recent archaeological activity has made evident traces of small palaces, houses and city walls but there is also an architectural heritage visible relative to other buildings – such as mosques and even small ‘ribat’(s) along the coastline. Some techniques, like that of ‘rammed earth’, are known to have been common in the Almohad period. In general terms, one can identify several remnants of buildings – religious, civil and military – with different construction techniques and traditions, not only the reuse of older constructions but also the erection of new buildings. On the other hand, it is possible to find parallels to these buildings in such varied areas as other parts of the ancient al-Andalus, North Africa, Syria and even Samarra (Iraq). This area of the Iberian Peninsula, described in chronicles as Gharb al-Andalus, is a hybrid region, where different traditions converged, taking advantage of the legacy of previous periods, mixing that legacy with contributions from North Africa, different areas of the Mediterranean and even the Middle East.