Annual Report for the Ecosystem Management Program Pohakuloa Training Area, Island of Hawaii August 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidance Document Pohakuloa Training Area Plant Guide

GUIDANCE DOCUMENT Recovery of Native Plant Communities and Ecological Processes Following Removal of Non-native, Invasive Ungulates from Pacific Island Forests Pohakuloa Training Area Plant Guide SERDP Project RC-2433 JULY 2018 Creighton Litton Rebecca Cole University of Hawaii at Manoa Distribution Statement A Page Intentionally Left Blank This report was prepared under contract to the Department of Defense Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP). The publication of this report does not indicate endorsement by the Department of Defense, nor should the contents be construed as reflecting the official policy or position of the Department of Defense. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the Department of Defense. Page Intentionally Left Blank 47 Page Intentionally Left Blank 1. Ferns & Fern Allies Order: Polypodiales Family: Aspleniaceae (Spleenworts) Asplenium peruvianum var. insulare – fragile fern (Endangered) Delicate ENDEMIC plants usually growing in cracks or caves; largest pinnae usually <6mm long, tips blunt, uniform in shape, shallowly lobed, 2-5 lobes on acroscopic side. Fewer than 5 sori per pinna. Fronds with distal stipes, proximal rachises ocassionally proliferous . d b a Asplenium trichomanes subsp. densum – ‘oāli’i; maidenhair spleenwort Plants small, commonly growing in full sunlight. Rhizomes short, erect, retaining many dark brown, shiny old stipe bases.. Stipes wiry, dark brown – black, up to 10cm, shiny, glabrous, adaxial surface flat, with 2 greenish ridges on either side. Pinnae 15-45 pairs, almost sessile, alternate, ovate to round, basal pinnae smaller and more widely spaced. -

5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation

Spermolepis hawaiiensis (no common name) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office Honolulu, Hawaii 5-YEAR REVIEW Species reviewed: Spermolepis hawaiiensis (no common name) TABLE OF CONTEN TS 1.0 GENERAL IN FORMATION .......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Reviewers ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Methodology used to complete the review:................................................................. 1 1.3 Background: .................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS....................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Application of the 1996 Distinct Population Segment (DPS) policy ......................... 3 2.2 Recovery Crite ria .......................................................................................................... 4 2.3 Updated Information and Current Species Status .................................................... 5 2.4 Synthesis......................................................................................................................... 8 3.0 RESULTS ........................................................................................................................ 15 3.3 Recommended Classification: ................................................................................... -

Pōhakuloa Training Area (PTA) Real Property Master Plan (RPMP)

Draft Finding of No Significant Impact Pōhakuloa Training Area Real Property Master Plan Adoption for Hawai‘i Island, Hawai‘i AUTHORITY Pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969, as amended (42 United States Code 4321-4347) (NEPA), the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) regulations for implementing NEPA (40 Code of Federal Regulations [CFR] parts 1500-1508), and the Final Rule on Environmental Analysis of Army Actions (32 CFR Part 651), the United States Army Garrison Hawaii (USAG-HI) gives notice that a Programmatic Environmental Assessment (PEA) has been prepared for adoption of the Pōhakuloa Training Area Real Property Master Plan, Hawai‘i Island, Hawai‘i. PROPOSED ACTION The U.S. Army (Army) proposes to adopt the Real Property Master Plan (RPMP) for the Pōhakuloa Training Area (PTA). The adoption of the RPMP is an administrative action that would not involve new development, ground disturbance, alteration of any real estate, facility or infrastructure, or change in training activities at PTA. The adoption of the PTA RPMP involves senior mission commander endorsement, recommendation by the installation Real Property Planning Board, and approval by the designated staff of the Installation Management Command (a field-operating agency of the Office, Assistant Chief of Staff for Installation Management). The Proposed Action is independent of the types of training and tempo of range activities taking place at PTA. It is not expected to result in changes to training tempo and intensity at PTA because these conditions are driven by national security threat assessments and the ebb and flow of international affairs. The PEA evaluates the environmental impacts of the RPMP adoption and includes analyses of the no- action alternative. -

Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service

Friday, April 5, 2002 Part II Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Revised Determinations of Prudency and Proposed Designations of Critical Habitat for Plant Species From the Island of Molokai, Hawaii; Proposed Rule VerDate Mar<13>2002 12:44 Apr 04, 2002 Jkt 197001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\05APP2.SGM pfrm03 PsN: 05APP2 16492 Federal Register / Vol. 67, No. 66 / Friday, April 5, 2002 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR the threats from vandalism or collection materials concerning this proposal by of this species on Molokai. any one of several methods: Fish and Wildlife Service We propose critical habitat You may submit written comments designations for 46 species within 10 and information to the Field Supervisor, 50 CFR Part 17 critical habitat units totaling U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific RIN 1018–AH08 approximately 17,614 hectares (ha) Islands Office, 300 Ala Moana Blvd., (43,532 acres (ac)) on the island of Room 3–122, P.O. Box 50088, Honolulu, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife Molokai. HI 96850–0001. and Plants; Revised Determinations of If this proposal is made final, section Prudency and Proposed Designations 7 of the Act requires Federal agencies to You may hand-deliver written of Critical Habitat for Plant Species ensure that actions they carry out, fund, comments to our Pacific Islands Office From the Island of Molokai, Hawaii or authorize do not destroy or adversely at the address given above. modify critical habitat to the extent that You may view comments and AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, the action appreciably diminishes the materials received, as well as supporting Interior. -

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office

U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE PACIFIC ISLANDS FISH AND WILDLIFE OFFICE ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF CRITICAL HABITAT DESIGNATION FOR 124 OAHU SPECIES Trematolobelia singularis Draft – February 2012 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION AND REPORT ORGANIZATION 5 PART I ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF PROPOSED CRITICAL HABITAT DESIGNATION FOR 123 OAHU SPECIES 6 CHAPTER 1 BACKGROUND 6 CHAPTER 2 FRAMEWORK 6 CHAPTER 3 PREVIOUS ECONOMIC ANALYSES OF CRITICAL 7 HABITAT DESIGNATIONS ON OAHU 3(a): Methodology 7 3(b): Water Resources Considerations 7 CHAPTER 4 OAHU ELEPAIO CRITICAL HABITAT RULE 8 4(a): Proposed Critical Habitat 8 4(b): Draft Economic Analysis 8 4(c): Economic Analysis Addendum 10 4(d): Critical Habitat Designation 11 CHAPTER 5 2003 CRITICAL HABITAT DESIGNATION FOR 99 11 OAHU PLANTS 5(a): Proposed Critical Habitat 11 5(b): Draft Economic Analysis 11 5(c): Economic Analysis Addendum 13 5(d): Critical Habitat Designation 14 CHAPTER 6 12 HAWAIIAN PICTURE-WING FLY SPECIES CRITICAL 15 HABITAT 6(a): Proposed Critical Habitat 15 6(b): Draft Economic Analysis 15 6(c): Final Economic Analysis 16 6(d): Critical Habitat Designation 17 6(e): Economic Analysis Addendum 17 CHAPTER 7 ECONOMIC IMPACT IN OVERLAP AREAS 17 7(a): Percent Overlap 17 7(b): Primary Constituent Elements, Part I 18 CHAPTER 8 PREVIOUSLY PREDICTED ECONOMIC IMPACTS 19 8(a): Section 7 Consultation Costs 19 8(a)(i): Formal Section 7 Consultations on Critical Habitat 19 8(a)(ii): Informal Consultations on Critical Habitat 20 2 8(b): Land Reclassification 20 8(c): Preservation and Watershed Management -

Final Report (Posted 10/19)

FINAL REPORT Remote Sensing Technology for Threatened and Endangered Plant Species Recovery ESTCP Project RC-201203 OCTOBER 2018 Erin Questad California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Susan Cordell USDA Forest Service Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry James Kellner Brown University Distribution Statement A This document has been cleared for public release Page Intentionally Left Blank This report was prepared under contract to the Department of Defense Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP). The publication of this report does not indicate endorsement by the Department of Defense, nor should the contents be construed as reflecting the official policy or position of the Department of Defense. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the Department of Defense. Page Intentionally Left Blank REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. -

The First Collection of Hawaiian Plants by David Nelson in 1779

Pacific Science (1978), vol. 32, no. 3 © 1979 by The University Press of Hawaii. All rights reserved The First Collection of Hawaiian Plants by David Nelson in 1779. Hawaiian Plant Studies 55 1 HAROLD ST. JOHN 2 CAPTAIN JAMES COOK initiated modern sci On this mountain trip Nelson collected entific exploratory expeditions. He made good specimens and then dried them. On possible discoveries in distant lands in as return to England, they were delivered to Sir tronomy, botany, and in many other sciences. Joseph Banks, who deposited them in the On his first world voyage (1768-1771), Sir British Museum of Natural History, where Joseph Banks and Dr. Daniel Solander they were studied by Dr. Daniel Solander. gathered plant specimens, and Sydney Par Solander classified and named some ofthem; kinson made plant portraits so numerous many were new genera and all but II were that most of them are still unpublished. On new species. After Solander's death, his the second voyage, Johann Reinhold Forster successor, Robert Brown, studied the residue and Georg Adam Forster made good col of Nelson's collections. The generic names lections, and published them in two books. given were mostly like Ilicoides for Pelea, On the third voyage, there were two natu Hydrangeoides for Perrottetia, Cestroides for rabsts, William Anderson (surgeon's mate Bohea, Coffeoides for Gouldia, Tachitoides _on the_Resolution) and young_David Nelson, for--Myrsine, -lresinoides- for (;har-pentiera, gardener and botanist (on the second ship, Moroides for Neraudia, etc. That is, their the Discovery). Anderson made little pretense !licoides was like !lex, Hydrangeoides was at collecting plants, became sickly, and died like Hydrangea, etc., since the Greek suffix halfway through the voyage. -

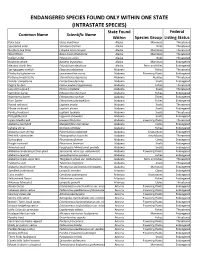

Endangered Species Only Found in One State

ENDANGERED SPECIES FOUND ONLY WITHIN ONE STATE (INTRASTATE SPECIES) State Found Federal Common Name Scientific Name Within Species Group Listing Status Polar bear Ursus maritimus Alaska Mammals Threatened Spectacled eider Somateria fischeri Alaska Birds Threatened Northern Sea Otter Enhydra lutris kenyoni Alaska Mammals Threatened Wood Bison Bison bison athabascae Alaska Mammals Threatened Steller's Eider Polysticta stelleri Alaska Birds Threatened Bowhead whale Balaena mysticetus Alaska Mammals Endangered Aleutian shield fern Polystichum aleuticum Alaska Ferns and Allies Endangered Spring pygmy sunfish Elassoma alabamae Alabama Fishes Threatened Fleshy‐fruit gladecress Leavenworthia crassa Alabama Flowering Plants Endangered Flattened musk turtle Sternotherus depressus Alabama Reptiles Threatened Slender campeloma Campeloma decampi Alabama Snails Endangered Pygmy Sculpin Cottus paulus (=pygmaeus) Alabama Fishes Threatened Lacy elimia (snail) Elimia crenatella Alabama Snails Threatened Vermilion darter Etheostoma chermocki Alabama Fishes Endangered Watercress darter Etheostoma nuchale Alabama Fishes Endangered Rush Darter Etheostoma phytophilum Alabama Fishes Endangered Round rocksnail Leptoxis ampla Alabama Snails Threatened Plicate rocksnail Leptoxis plicata Alabama Snails Endangered Painted rocksnail Leptoxis taeniata Alabama Snails Threatened Flat pebblesnail Lepyrium showalteri Alabama Snails Endangered Lyrate bladderpod Lesquerella lyrata Alabama Flowering Plants Threatened Alabama pearlshell Margaritifera marrianae Alabama Clams -

Analysis of Fire History and Management Concerns at Pohakuloa Training Area

Analysis of Fire History and Management Concerns at Pohakuloa Training Area Andrew M. Beavers Robert E. Burgan Center for Environmental Management of Military Lands Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 80523-1490 CEMML TPS 02-02 April 2002 Analysis of Fire History and Management Concerns At Pohakuloa Training Area December 19, 2000 Submitted by Andrew M. Beavers Fire Ecologist/Behaviorist Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO Reviewed by Robert E. Burgan USDA Forest Service (Retired) Intermountain Fire Science Lab, Missoula, MT TPS 02-02 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................................. 1 General Description .................................................................................................................................................... 2 Fire Effects on Hawaiian Ecosystems........................................................................................................................ 5 Fire History of Pohakuloa Training Area............................................................................................................... 10 1.1 Summary .......................................................................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Fire History Methods ...................................................................................................................................... -

Endangered Status for 23 Species on Oahu and Designation of Critical Habitat for 124 Species; Final Rule

Vol. 77 Tuesday, No. 181 September 18, 2012 Part II Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Endangered Status for 23 Species on Oahu and Designation of Critical Habitat for 124 Species; Final Rule VerDate Mar<15>2010 18:28 Sep 17, 2012 Jkt 226001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\18SER2.SGM 18SER2 tkelley on DSK3SPTVN1PROD with RULES2 57648 Federal Register / Vol. 77, No. 181 / Tuesday, September 18, 2012 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR preamble or at http://www.regulations. by nonnative pigs, goats, rats, and gov. invertebrates; and predation on the Fish and Wildlife Service FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: three damselflies by nonnative fish, Loyal Mehrhoff, Field Supervisor, bullfrogs, and ants. 50 CFR Part 17 • Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office Some of the plant species face the (see ADDRESSES above). If you use a additional threat of trampling. [Docket No. FWS–R1–ES–2010–0043: • The inadequacy of existing 4500030114] telecommunications device for the deaf (TDD), you may call the Federal regulatory mechanisms (specifically, RIN 1018–AV49 Information Relay Service (FIRS) at inadequate protection of habitat and 800–877–8339. inadequate protection from the introduction of nonnative species) poses Endangered and Threatened Wildlife SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: and Plants; Endangered Status for 23 a current and ongoing threat to all 23 Species on Oahu and Designation of Executive Summary species. • Critical Habitat for 124 Species Why we need to publish a rule. This There are current and ongoing is a final rule to list 23 species as threats to nine plant species and the AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, endangered under the Act, including 20 three damselflies due to factors Interior. -

Priority Species of Pōhakuloa Training Area

CHAPTER 1: SPECIES SPECIFIC GOALS 1.1 INTRODUCTION SPECIES SPECIFIC GOALS The rare plant monitoring programs and the rare animal survey and monitoring programs are designed to provide information that will lead towards an increased understanding of the species at PTA. The information gained from these programs is incorporated into the management actions identified for Intensive Management Units (IMU) with the goal of improved management of the species and habitat. 1.2 INTRODUCTION – RARE PLANT MONITORING Due to PTA’s land use history and isolation, access to the area has been limited. As a result PTA harbors unique ecosystems and vegetation. For example, PTA is one of the largest intact sub-alpine dryland forests remaining in the state. Not only is the ecosystem itself rare but so are many of its components. For example, at PTA there are eleven endangered species, one threatened species, and eleven species of concern, including one undescribed species. Six of these plant species are found only at PTA and two species are found at PTA and one or two other locations in the state. A Priority Species (PS) list was developed to prioritize monitoring and management actions. Schiedea hawaiiensis and Tetramolopium sp. 1 are the only PS-1 plants, which are not federally listed. These species of concern are included because S. hawaiiensis has less than 20 naturally occurring individuals and T. sp. 1 has less than 100 known individuals. Therefore, they receive the highest priority for management actions. The Priority Species list has been defined and species assigned as follows. Priority Species of Pōhakuloa Training Area Priority Species-1 (PS-1) – Plant species with fewer than 500 individuals and/or 5 or fewer populations remaining statewide. -

Initial Draft HCP Honuaula

DRAFT Habitat Conservation Plan for HONUA‘ULA (WAILEA 670) KI HEI, MAUI PREPARED FOR: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources APPLICANT: Honua‘ula Partners, LLC 381 Huku Li‘i Place, Suite 202 Kīhei, Maui 96753 PREPARED BY: SWCA Environmental Consultants Honolulu Office Bishop Square: ASB Tower 1001 Bishop Street, Suite 2800 Honolulu, HI. 96813 December 2012 DRAFT HCP for Honuaʻula / Wailea 670, Kīhei, Maui This page intentionally left blank © 2012 SWCA Environmental Consultants DRAFT HCP for Honuaʻula / Wailea 670, Kīhei, Maui TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION AND PROJECT OVERVIEW............................................................................. 1 1.1 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Applicant ..................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Regulatory Context ....................................................................................................... 5 1.3.1 Federal Endangered Species Act (16 U.S.C. 1531-1544)............................................... 5 1.3.2 Federal National Environmental Policy Act (42 U.S.C. 4371 et seq.) ............................... 7 1.3.3 Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act (16 U.S.C. 703-712) ................................................ 7 1.3.4 Federal National Historic Preservation Act (16 U.S.C. 470-470b, 470c-470n) .................. 7 1.3.5 Hawai‘i Revised Statutes, Chapter