Downloaded and Used for As Many Ends As There Are Downloaders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Hans Arp After 1945

Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 Volume 2 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers Volume 2 The Art of Arp after 1945 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Table of Contents 10 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning 12 Foreword Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger 16 The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 An Introduction Maike Steinkamp 25 At the Threshold of a New Sculpture On the Development of Arp’s Sculptural Principles in the Threshold Sculptures Jan Giebel 41 On Forest Wheels and Forest Giants A Series of Sculptures by Hans Arp 1961 – 1964 Simona Martinoli 60 People are like Flies Hans Arp, Camille Bryen, and Abhumanism Isabelle Ewig 80 “Cher Maître” Lygia Clark and Hans Arp’s Concept of Concrete Art Heloisa Espada 88 Organic Form, Hapticity and Space as a Primary Being The Polish Neo-Avant-Garde and Hans Arp Marta Smolińska 108 Arp’s Mysticism Rudolf Suter 125 Arp’s “Moods” from Dada to Experimental Poetry The Late Poetry in Dialogue with the New Avant-Gardes Agathe Mareuge 139 Families of Mind — Families of Forms Hans Arp, Alvar Aalto, and a Case of Artistic Influence Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen 157 Movement — Space Arp & Architecture Dick van Gameren 174 Contributors 178 Photo Credits 9 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning Hans Arp’s late work after 1945 can only be understood in the context of the horrific three decades that preceded it. The First World War, the catastro- phe of the century, and the Second World War that followed shortly thereaf- ter, were finally over. -

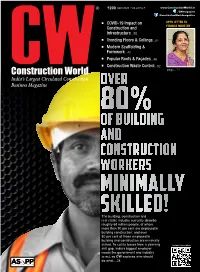

Over of Building and Construction Workers

`200 April 2020 • Vol.22 No.7 www.ConstructionWorld.in /CWmagazine /ConstructionWorldmagazine COVID-19 Impact on OPEN LETTER TO Construction and FINANCE MINISTER Infrastructure...38 Trending Floors & Ceilings...64 Modern Scaffolding & Formwork...40 Popular Roofs & Façades...46 Construction Waste Control...52 page...14 Over 80% of building and construction workers minimally skilled! The building, construction and real estate industry currently absorbs roughly 68 million people, of whom more than 90 per cent are deployed in building construction; and over 80 per cent of those employed in building and construction are minimally skilled. To cut its losses from a yawning Instant Subscription skill gap, India’s biggest employer needs the government and industry to act, as CW explores who should do what....28 SmartCitiesCouncil India LIVABILITY WORKABILITY SUSTAINABILITY JOIN WORLD-CLASS COMPANIES HELP CITIES BECOME MORE SUSTAINABLE WHAT the Council does... Smart Cities Council works with city leaders & officials across the country to make their cities more livable, workable and sustainable We give cities trusted, vendor-neutral guidance and best practices from the country’s leading experts. It provides Awareness, Advocacy, and Action. The Council gets cities ready to adopt smart technologies and connects them with our partners, who are leading stakeholders in the ecosystem Website: India.SmartCitiesCouncil.com FEW OF OUR PARTNERS TO KNOW MORE CONTACT: Tanveer Padode | Manager - Operations | Tel: 022 24175738 | Mob: +91 9324579821 | Emaill: [email protected] RESPOND (5T307) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN (05761) + RESPOND COLOR (5T310) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN LAKE (05327) | INSTALLED BRICK RESPOND (5T307) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN (05761) + RESPOND COLOR (5T310) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN LAKE (05327) | INSTALLED BRICK RESPOND (5T307) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN (05761) + RESPOND COLOR (5T310) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN LAKE (05327) | INSTALLED BRICK Step into a space designed to engage, evolve and revitalize the senses. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

NMMS Staff Kick Off New School BRISTOL — a Group Said

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2017 FREE IN PRINT, FREE ON-LINE • WWW.NEWFOUNDLANDING.COM COMPLIMENTARY Public hearing set on Town Hall project BY THOMAS P. CALDWELL hearing. A work session the existing municipal a new town hall on prop- sion. police station,” Solomon Contributing Writer on Sept. 29 will focus on building to serve only erty next door which the “We want to create a said, explaining that the BRISTOL — Samyn- putting cost figures with the Bristol Police De- town had purchased for new center with an invit- driveway would go be- D’Elia Architects of Ash- the conceptual floor partment and building possible future expan- ing front entrance to the SEE TOWN HALL, PAGE A14 land, hired last May to plans, in preparation for create preliminary plans the hearing. for a solution to the space Duncan, who had of- needs of the Bristol Mu- fered the amendment at nicipal Building, will the 2016 Town Meeting offer some drawings for that set the process in public review at the Old motion, and served on Town Hall on Wednes- the space needs commit- day, Aug. 4, at 7 p.m. tee when it came up with Architect Cris Solo- the recommendation mon joined space needs for two buildings, said committee member Su- the committee reviewed san Duncan in giving the options again with the Bristol Board of Se- Samyn-D’Elia to see if lectmen an advance look they could meet all the at the drawings on Sept. needs with renovations 21, noting that the de- to the existing building. sign work is still in prog- Solomon said they are ress and the plans could still recommending two change before the public buildings, converting Newfound parents COURTESY — CHRIS DYER renew push for Rainbow over Newfound Chris Dyer of Bristol spotted a full rainbow over Newfound Lake last week, and captured this beautiful scene with his camera. -

A Collection of Poems and Songs) Del Vaugh Schmidt Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1989 Waitin' for the blow (a collection of poems and songs) Del Vaugh Schmidt Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Vaugh Schmidt, Del, "Waitin' for the blow (a collection of poems and songs)" (1989). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 204. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/204 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -------- Waitin' for the blow (A collection of poems and songs) by Del Vaughn Schmidt A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: English (Creative Writing) Approved: Signature redacted for privacy //"' Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy For College Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1989 ----------- ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE iv POEMS 1 Feeding the Horses 2 The Barnyard 3 Colorado, Summer 1979 5 Arrival 8 Aliens 10 Communicating 12 Home 13 Jeff 15 Waitin' for the Blow 17 Real Surreal 21 Stove Wall 22 Positive 25 Playin' 26 Maybe it's the Music 27 SONGS 31 Have Another (for Colorado) 32 Wake Up 34 Unemployment Blues 36 Players 37 Train We're On 38 Institution 40 iii Farmer's Lament 42 Space Blues 44 You Would Have Made the Day 45 Four Nights in a Row 47 Helpless Bound 49 Carpenter's Blues 50 Hills 51 iv PREFACE Up to the actual point of writing this preface, I have never given much deep thought as to the difference between writing song lyrics and poetry. -

Nothing Happened

NOTHING HAPPENED A History Susan A. Crane !"#$%&'( )$*+,'-*". /',-- Stanford, California !"#$%&'( )$*+,'-*". /',-- Stanford, California ©2020 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Crane, Susan A., author. Title: Nothing happened : a history / Susan A. Crane. Description: Stanford, California : Stanford University Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020013808 (print) | LCCN 2020013809 (ebook) | ISBN 9781503613478 (cloth) | ISBN 9781503614055 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: History—Philosophy. | Collective memory. Classification: LCC D16.9 .C73 2020 (print) | LCC D16.9 (ebook) | DDC 901—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020013808 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020013809 Cover design: Rob Ehle Cover photos: Historical marker altered from photo (Brian Stansbury) of a plaque commemorating the Trail of Tears, Monteagle, TN, superimposed on photo of a country road (Paul Berzinn). Both via Wikimedia Commons. Text design: Kevin Barrett Kane Typeset at Stanford University Press in 11/15 Mercury Text G1 A mind lively and at ease can do with seeing nothing, and can see nothing that does not answer. J#$, A0-",$, E MMA CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Episodes in a History of Nothing 1 EPISODE 1 Studying How Nothing Happens 21 EPISODE 2 Nothing Is the Way It Was 67 EPISODE 3 Nothing Happened 143 CONCLUSION There Is Nothing Left to Say 217 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks for Nothing 223 Notes! 227 Index 239 NOTHING HAPPENED Introduction EPISODES IN A HISTORY OF NOTHING !"#$# %&'()"**# +'( ,#**-. -

Black Pumas - Colors Episode 191

Song Exploder Black Pumas - Colors Episode 191 Hrishikesh: You’re listening to Song Exploder, where musicians take apart their songs and piece by piece tell the story of how they were made. My name is Hrishikesh Hirway. (“Colors” by BLACK PUMAS) Hrishikesh: Black Pumas formed in Austin, Texas in 2017, when singer Eric Burton met producer Adrian Quesada. Their self-titled debut was released in June 2019, and got them a Grammy nomination for Best New Artist. In this episode, they break down their hit song “Colors,” which Eric started writing ten years ago, when he was first learning how to play guitar. (“Colors” by BLACK PUMAS) Eric: My name is Eric Burton, and I sing and write music for the Black Pumas. (Music fades out) Eric: I wrote “Colors” probably a little bit over 10 years ago. At the time, I was leading praise and worship at this Presbyterian Church, and the hymnal music just wasn't doing it for me at the level that I was kind of yearning for it to happen. I loved experiencing the beautiful hymns and the airy music for what it was, but I wasn't attracted that much to singing those songs over and over again before creating my own. I always wanted to see like what a hymn might sound like from Eric Burton. (Acoustic guitar plucking) Eric: When the song first came to me, I was taking a nap on my uncle's rooftop actually, and I was having such a great day. The weather was great, the sunset looked pretty amazing, as it always does in New Mexico anyway, and I was just singing to, you know, exactly what I saw. -

A Poem Is a Mushroom on Keeping the Strangeness in Your Work

A Poem is a Mushroom On Keeping the Strangeness in Your Work SYLVIA PLATH Tulips The tulips are too excitable, it is winter here. Look how white everything is, how quiet, how snowed-in. I am learning peacefulness, lying by myself quietly As the light lies on these white walls, this bed, these hands. I am nobody; I have nothing to do with explosions. I have given my name and my day-clothes up to the nurses And my history to the anesthetist and my body to surgeons. They have propped my head between the pillow and the sheet-cuff Like an eye between two white lids that will not shut. Stupid pupil, it has to take everything in. The nurses pass and pass, they are no trouble, They pass the way gulls pass inland in their white caps, Doing things with their hands, one just the same as another, So it is impossible to tell how many there are. My body is a pebble to them, they tend it as water Tends to the pebbles it must run over, smoothing them gently. They bring me numbness in their bright needles, they bring me sleep. Now I have lost myself I am sick of baggage—— My patent leather overnight case like a black pillbox, My husband and child smiling out of the family photo; Their smiles catch onto my skin, little smiling hooks. I have let things slip, a thirty-year-old cargo boat stubbornly hanging on to my name and address. They have swabbed me clear of my loving associations. -

R BABY FOUNDATION Presents a Benefit Concert: ROCKIN' to SAVE BABIES' LIVES

R BABY FOUNDATION Presents a Benefit Concert: ROCKIN' TO SAVE BABIES' LIVES Artists Align to Raise Awareness for Critical Improvements in Emergency Pediatric Care Featuring Performances By A GREAT BIG WORLD, MARY LAMBERT, RYAN STAR & DJ CASSIDY July 23 at The Hammerstein Ballroom in New York City Tickets on Sale Now! NEW YORK, June 9, 2014 /PRNewswire-USNewswire/ -- R BABY Foundation (www.rbabyfoundation.org) – the first and only not-for-profit organization focused on saving babies' lives through improving pediatric emergency care – is pleased to announce a benefit concert, Rockin' To Save Babies' Lives at The Hammerstein Ballroom in New York City on July 23, 2014. Featuring performances by multi-platinum New York duo A GREAT BIG WORLD, Grammy nominated singer-songwriter MARY LAMBERT, alternative rock musician RYAN STAR and Columbia recording artist DJ CASSIDY, this special event is poised to be one of the concert highlights of the summer and will directly fund R Baby Foundation's proven emergency healthcare programs for babies and children in the United States and beyond its borders. Tickets may be purchased at www.rbabyfoundation.org and range from $100 - $500; VIP packages are available and include premium floor access with food/beverages. Tickets are tax deductible. "The state of emergency healthcare in the United States is critically lacking for babies," explains Andrew Rabinowitz, co-founder and President of the R Baby Foundation. "Infant mortality and lack of preparedness in non-pediatric emergency departments continue to be worldwide issues. Emergency Room doctors spend only 8% of their training in pediatric emergencies; yet up to one-third of their future patients will be children. -

13-46 Show Date: Weekend of November 16-17, 2013 Disc One/Hour One Opening Billboard: None Seg

Show Code: #13-46 Show Date: Weekend of November 16-17, 2013 Disc One/Hour One Opening Billboard: None Seg. 1 Content: #40 “THE MONSTER” – Eminem f/Rihanna #39 “I NEED YOUR LOVE” – Calvin Harris f/Ellie Goulding #38 “ALONE TOGETHER” – Fall Out Boy Commercials: :30 Zazzle.com :30 Taco Bell :30 Novartis/NO DOZ :30 Match.com Outcue: “...match dot com.” Segment Time: 15:09 Local Break 2:00 Seg. 2 Billboard: Telestrations Content: #37 “WHITE WALLS” – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis f/Schoolboy Q & Hollis #36 “SAME LOVE” – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis f/Mary Lambert #35 “TREASURE” – Bruno Mars #34 “CROOKED SMILE” – J. Cole f/TLC Commercials: :30 Telestrations :30 Sierra Mist :30 Progressive :30 Subway Outcue: “...be bold. Eat fresh.” Segment Time: 18:55 Local Break 2:00 Seg. 3 Billboard: Zazzle Content: #33 “TIMBER” – Pitbull f/Ke$ha #32 “MIRRORS” – Justin Timberlake #31 “SAIL” – AWOLNATION On The Verge: “ALL NIGHT” – Icona Pop Commercials: :30 Proactiv :30 Novartis/NO DOZ Outcue: “...other caffeine sources.” Segment Time: 15:41 Local Break 1:00 Seg. 4 ***This is an optional cut - Stations can opt to drop song for local inventory*** Content: AT40 Extra: “ROLLING IN THE DEEP” – Adele Outcue: “…taste of that.” (sfx) Segment Time: 4:11 Hour 1 Total Time: 58:56 END OF DISC ONE Show Code: #13-46 Show Date: Weekend of November 16-17, 2013 Disc Two/Hour Two Opening Billboard None Seg. 1 Content: #30 “GET LUCKY” – Daft Punk f/Pharrell Williams #29 “LOVE SOMEBODY” – Maroon 5 #28 “ROUGH WATER” – Travie McCoy f/Jason Mraz On The Verge: “HEART ATTACK” – Enrique Iglesias Commercials: :60 Match.com :30 Sierra Mist :30 Zazzle.com Outcue: “...zazzle dot com.” Segment Time: 17:34 Local Break 2:00 Seg. -

Inside Official Singles & Albums • Airplay Charts • Compilations & Indie Charts

ChartPack cover_v1_News and Playlists 20/01/14 11:18 Page 35 CHARTPACK Bruce Springsteen tops The Official UK Artist Albums Chart with High Hopes INSIDE OFFICIAL SINGLES & ALBUMS • AIRPLAY CHARTS • COMPILATIONS & INDIE CHARTS 26-27 Singles-Albums_v1_News and Playlists 20/01/14 11:02 Page 28 CHARTS UK SINGLES WEEK 3 For all charts and credits queries email [email protected]. Any changes to credits, etc, must be notified to us by Monday morning to ensure correction in that week’s printed issue Key H Platinum (600,000) THE OFFICIAL UK SINGLES CHART l Gold (400,000) l Silver (200,000) THIS LAST WKS ON ARTIST / TITLE / LABEL CATALOGUE NUMBER (DISTRIBUTOR) THIS LAST WKS ON ARTIST / TITLE / LABEL CATALOGUE NUMBER (DISTRIBUTOR) WK WK CHRT (PRODUCER) PUBLISHER (WRITER) WK WK CHRT (PRODUCER) PUBLISHER (WRITER) 1 9 PHARRELL WILLIAMS Happy Back Lot USQ4E1300686 (Back Lot) 41 47 BASTILLE Pompeii Virgin GB1201200092 (Arvato) 1 (Pharrell) EMI/Universal (Williams) 39 (Smith/Crew) Universal (Smith) 2 3 PITBULL FT KE$HA Timber J/MR 305/Polo Grounds USRC11301695 (Arvato) 30 10 LILY ALLEN Somewhere Only We Know Parlophone GBAYE1301770 (Arvato) 2 (Dr. Luke/Cirkut/Sermstyle/Seeley) Sony ATV/BMG Chrysalis/Warner Chappell/Prescription/Power Pen/Where Da Kasz At/Abuela y Tia/Kasz Money/Oneirology/Artist 101 (various) 40 (Beard) Universal (Rice-Oxley/Chaplin/Hughes) 3 17 AVICII Hey Brother Positiva/PRMD CH3131340084 (Arvato) 23 5 SAM BAILEY Skyscraper Syco GBHMU1300327 (Arvato) 3 (Bergling) Sony ATV/EMI/Universal (Bergling/Pournouri/Al Fakir/Pontare/Maggio) -

Inside the White Cube: the Ideology of the Gallery Space

Inside the White Cube The Ideology of the Gallery Space Brian O'Doherty Introduction by Thomas McEvilley The Lapis Press Santa Monica San Francisco Copyright © 1976, 1986 by Brian O'Doherty Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the United States Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. The essays in this book originally appeared in Artforum magazine in 1976 in a somewhat different form. First book edition 1986 90 89 88 87 86 5 4 3 2 1 The Lapis Press 1850 Union Street, Suite 466 San Francisco, CA 94123 ISBN 0-932499-14-7 cloth ISBN 0-932499-05-8 paper Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 85-081090 Contents Acknowledgements 6 Introduction by Thomas McEvilley 7 I. Notes on the Gallery Space 13 A Fable of Horizontal and Vertical . Modernism . The Properties of the Ideal Gallery . .The Salon . .The Easel Picture . .The Frame as Editor . Photography . Impressionism . .The Myth of the Picture Plane . Matisse . Hanging . .The Picture Plane as Simile . .The Wall as Battleground and "Art" . .The Installation Shot .... II. The Eye and the Spectator 35 Another Fable . Five Blank Canvasses . Paint, Picture Plane, Objects . Cubism and Collage . Space . .The Spectator . .The Eye . Schwitters's Merzbau . .Schwitters's Performances . .Happenings and Environments . Kienholz, Segal, Kaprow . Hanson, de Andrea . Eye, Spectator, and Minimalism . Paradoxes of Experience . Conceptual and Body Art.... III. Context as Content 65 The Knock at the Door .