Nothing Happened

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{Download PDF} David Bowie: Starman

DAVID BOWIE: STARMAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Paul Trynka | 544 pages | 18 Jul 2011 | Little Brown and Company | 9780316032254 | English | London, United Kingdom David Bowie: Starman PDF Book He told me: Let the children lose it Let the children use it Let all the children boogie. Wednesday 8 July Friday 22 May September Glam rock [1]. Tuesday 26 May Song Styles. Archived from the original on 3 November Energetic Happy Hypnotic. Don't want to see ads? The starmen that he is talking about are called the infinites, and they are black-hole jumpers. Thursday 3 September He was a leading figure in the music industry and is… read more. Tuesday 4 August The band thereafter idolised Bowie and subsequently covered " Ziggy Stardust " in The Best Rock Anthems Wednesday 2 September Thursday 14 May Thursday 16 July Various Artists I Love 2 Party Thursday 27 August Saturday 9 May Monday 4 May Song Themes. Tuesday 5 May Monday 29 June Tuesday 20 October Tuesday 8 September Blues Classical Country. Sexy Trippy All Moods. David Bowie: Starman Writer The Singles Collection. With David Bowie there is always a bridge between the past and the future. Thursday 8 October Teenagers, children see Life on Mars , are endowed with much more immediate perception, without the intellectual superstructures typical of the bourgeois England. David Bowie The Singles Collection. The chorus is loosely based on " Over the Rainbow " from the film The Wizard of Oz , alluding to the "Starman"'s extraterrestrial origins over the rainbow the octave leap on "Star- man " is identical to that of Judy Garland 's "some- where " in "Over the Rainbow". -

Spring Magazine Dean’S Welcome Spring 2015

Spring Magazine Dean’s Welcome Spring 2015 We welcome spring and the beauty of its message, both literal and figurative, that this is a time to start fresh, to bloom, and to smell the roses. The School of Humanities is itself springing forward—six faculty books have published since January with three more coming out in April, innovative new courses are being offered, our students are completing award-winning research and we continue to build relationships with foundations and community leaders who believe in our mission. Inside of this magazine, we pick up from where we left off in our Annual Report. You’ll get an in-depth look at what our faculty, students and alumni are accomplishing. I express my gratitude to professors Jonathan Alexander, Erika Hayasaki, Tiffany Willoughby-Herard, Claire Jean Kim and Kristen Hatch for sharing their latest research with us; to students Jessica Bond and Jazmyne McNeese for letting us see how studying the humanities is shaping their worldviews and life ambitions; and to alumnae Pheobe Bui and Aline Ohanesian for showing us where a humanities education has taken them today. I encourage you to keep in touch with us and the school’s latest developments by joining on us Facebook and Twitter and by staying tuned every second Tuesday of the month for timely faculty-led insight into today’s most topical issues via Humanities Headlines, our exclusive webinar series. If you are local, take a look at the events listed at the end of the magazine--we’d love to see you there. Sincerely, Georges Van Den Abbeele Dean, School of the Humanities SCHOOL UPDATES SPRING | 2015 3 Humanities Studio Embodies UCI’s Global Mission with Language Tools & World-Class space where students and faculty can learn, teach, and conduct research with support from staff who understand their needs,” said Franz. -

I D II Ill TE 001 549 69 R

DEPARTMENT bF HEALTH, EDUCATION,AND WELFARE OE FORM 6000, 2169 OFFICE OF EDUCATION tillt.;Kt.1-1.)1%Iilr..UIVIC. ERIC ACC. NO. ED 032 316 IS DOCUMENTCOPYRIGHTED? YES NO0 fit CH ACC. NO. P.A.PUBL. DATE. I ESTI\N 71031CREPRODUCTION RELEASE? YES 0 NO i LEVELOF AVAILABILITY I D II Ill TE 001 549 69 R -.... AUTHOR Sohn, David A. Stucker, Melinda . TITLE Film Study in the Elementary School: Grades Kindergartenthrough Eight. A Curriculum Report to the American Film Institute. SOURCE CODEINSTITUTIONSOURCE) J1M25110 SP. AG. CODESPONSORING AGENCY BBB01992 . EDRS PRICE CONTRACT NO. GRANT NO. 1.25;14.60 REPORT. NO. BUREAU NO. AVAILABILITY JOURNAL CITATION DESCRIPTIVE NOTE 290p. DESCRIPTORS *Film Study; *Elementary Grades; *Instructional Aids; *ProgramEvaluation; *Films; Experimental Programs; Audiovisual Aids; Audiovisual Communication;Cartoons; Mass Media; Photography; Sound Effects; Sound Films; Teaching Methods;Teacher. Attitudes; Student Reaction; Student Attitudes IDENTIFIERS I . ABSTRACT The first and major portion of this 'report of ,a film study projectin Evanston, Illinois, lists films selected for use in grades 1-8, together with plotsummaries of varying lengths, special uses for the films, suggested study questionsand activities, sample student responses to questions and assignments,running times, appropriate age levels, and sourceslor ordering the filmt. Theresults of an evaluation of the film program as determined by questionnaires distributed to students and teachers are presented in parts two and three. A briefconclusion on the overall response to the program and the addresses of filmdistributors conclude the publication. (LH) . -... U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION d WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

O Desconcerto Anarquista De John Cage

Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Ciências Sociais Gustavo Ferreira Simões o desconcerto anarquista de john cage Doutorado em Ciências Sociais São Paulo 2017 ! Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Ciências Sociais Gustavo Ferreira Simões o desconcerto anarquista de john cage Tese apresentada à Banca Examinadora da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, como exigência parcial para obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências Sociais sob orientação do Prof. Dr. Edson Passetti. São Paulo 2017 ! ______________________ ______________________ ______________________ ______________________ ______________________ ! RESUMO Em 1988, John Cage inventou Anarchy , livro em que, a partir de escritos experimentais, valorizou as vidas de mulheres e homens anarquistas que marcaram seu percurso ético-estético libertário desde meados dos anos 1940 até a década de 1990, quando em seus últimos trabalhos, “number pieces” (1987-1992), apresentou o que denominou “harmonia anárquica”. Foi a partir da coexistência com artistas e militantes na Black Mountain College, no final da década de 1940, assim como em Nova York com o The Living Theatre (TLT) , que o artista já conhecido por seu corajoso “piano preparado” passou a elaborar o anarquismo como prática de vida. “4’33” (1952), ação direta contra a representação musical dos sons e em favor da incorporação dos ruídos excluídos pelas salas de concerto, irrompeu empolgada por essa aproximação libertária. Nas décadas seguintes, vivendo ao lado de artistas e anarquistas, afastado da cidade, em Stonypoint, iniciou a publicação de how to improve the world (you only make matters worse) (1965-1982), diário mantido por mais de quinze anos e no qual apresentou a lida com os escritos de Henry David Thoreau, preocupações antimilitares e ecológicas. -

Music & Entertainment Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction 20th February 2018 at 10.00 For enquiries relating to the sale, Viewing: 19th February 2018 10:00 - 16:00 Please contact: Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One, 81 Greenham Business Park, NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Christopher David Martin David Howe Fax: 0871 714 6905 Proudfoot Music & Music & Email: [email protected] Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment www.specialauctionservices.com Music As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to the auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indica- tions of provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price Historic Vocal & other Records 9. Music Hall records, fifty-two, by 16. Thirty-nine vocal records, 12- Askey (3), Wilkie Bard, Fred Barnes, Billy inch, by de Tura, Devries (3), Doloukhanova, 1. English Vocal records, sixty-three, Bennett (5), Byng (3), Harry Champion (4), Domingo, Dragoni (5), Dufranne, Eames (16 12-inch, by Buckman, Butt (11 - several Casey Kids (2), GH Chirgwin, (2), Clapham and inc IRCC20, IRCC24, AGSB60), Easton, Edvina, operatic), T Davies(6), Dawson (19), Deller, Dwyer, de Casalis, GH Elliot (3), Florrie Ford (6), Elmo, Endreze (6) (39, in T1) £40-60 Dearth (4), Dodds, Ellis, N Evans, Falkner, Fear, Harry Fay, Frankau, Will Fyfe (3), Alf Gordon, Ferrier, Florence, Furmidge, Fuller, Foster (63, Tommy Handley (5), Charles Hawtrey, Harry 17. -

Lessons Learned from Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

LESSONS LEARNED FROM JUSTICE RUTH BADER GINSBURG Amanda L. Tyler* INTRODUCTION Serving as a law clerk for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in the Supreme Court’s October Term 1999 was one of the single greatest privileges and honors of my life. As a trailblazer who opened up opportunities for women, she was a personal hero. How many people get to say that they worked for their hero? Justice Ginsburg was defined by her brilliance, her dedication to public service, her resilience, and her unwavering devotion to taking up the Founders’ calling, set out in the Preamble to our Constitution, to make ours a “more perfect Union.”1 She was a profoundly dedicated public servant in no small measure because she appreciated just how important her role was in ensuring that our Constitution belongs to everyone. Whether as an advocate or a Justice, she tirelessly fought to dismantle discrimination and more generally to open opportunities for every person to live up to their full human potential. Without question, she left this world a better place than she found it, and we are all the beneficiaries. As an advocate, Ruth Bader Ginsburg challenged our society to liber- ate all persons from the gender-based stereotypes that held them back. As a federal judge for forty years—twenty-seven of them on the Supreme Court—she continued and expanded upon that work, even when it meant in dissent calling out her colleagues for improperly walking back earlier gains or halting future progress.2 In total, she wrote over 700 opinions on the D.C. -

**V************************************ Reproductions Supplied by Edits Are the Best That Can Be Made Froa Tae Original Document

D0006661 RESUME ED 166 926 CS 205 566 AUTdOR Spann, Sylvia, El.; Culp, Mary Beth, Ed. TITLE Thematic Units in leaching English and the dumanities. Second Supplement. INsTirurION National Couacil of Teachers of English, Urbana, PUB DATE 30 NOTE 159p. AVAILABLE FRO3 Sational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 53755, $6.50-member, $7.00 non-member). EDRS PRICE SF01/PCO7 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Advertising; Communication Skills; Curriculum Development; *English Instruction; Futures (of Society); History; *Humanities: Justice: Listening Sicills; Logic; Politics; Popular Culture: Resource Units; Schools; Secondary Education; *Teaching Guides; *Thematic Approach; *Units of Study; Writing Instruction; Writing Skills ABSTRACT Tae seven units in this second supplement to "Thematic Units" focus oa communication skills, offering English teachers conteaporary plans for teaching writing, listening, persuasion, and'reasoning. The units were selected for their humanistic approaches to student language learning, combining English instruction with,topics in the humanities. Each unit contains comments from the teacher who developed the unit, an overview of the unit, general obfectives, evaluation methods, daily lesson plans and activities, study guides, resource materials, and other appropriate suggestions and at:dchments. The topics of the units are the school system, logic, nostaigia (studying the popular culture ofa past decade), futurism as a framework for composition instruction, advertising, politics, and law and justice. (RL) ********************************v************************************ Reproductions supplied by EDitS are the best that can be made froa tae original document. *********************************************************************** U S DEPARTMENT OF nEALTN. EDUCATION A TVILITAIIE NTMNAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION TmpSDOC UMENT HAS BEEN REPRO. nur.t.,E.A Fl V AS RECEIVED FROM 111 -Admai-i-ka *HI Pf RsON OR ORCAN QAT tON OSI 'GIN- I. -

The Art of Hans Arp After 1945

Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 Volume 2 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers Volume 2 The Art of Arp after 1945 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Table of Contents 10 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning 12 Foreword Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger 16 The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 An Introduction Maike Steinkamp 25 At the Threshold of a New Sculpture On the Development of Arp’s Sculptural Principles in the Threshold Sculptures Jan Giebel 41 On Forest Wheels and Forest Giants A Series of Sculptures by Hans Arp 1961 – 1964 Simona Martinoli 60 People are like Flies Hans Arp, Camille Bryen, and Abhumanism Isabelle Ewig 80 “Cher Maître” Lygia Clark and Hans Arp’s Concept of Concrete Art Heloisa Espada 88 Organic Form, Hapticity and Space as a Primary Being The Polish Neo-Avant-Garde and Hans Arp Marta Smolińska 108 Arp’s Mysticism Rudolf Suter 125 Arp’s “Moods” from Dada to Experimental Poetry The Late Poetry in Dialogue with the New Avant-Gardes Agathe Mareuge 139 Families of Mind — Families of Forms Hans Arp, Alvar Aalto, and a Case of Artistic Influence Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen 157 Movement — Space Arp & Architecture Dick van Gameren 174 Contributors 178 Photo Credits 9 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning Hans Arp’s late work after 1945 can only be understood in the context of the horrific three decades that preceded it. The First World War, the catastro- phe of the century, and the Second World War that followed shortly thereaf- ter, were finally over. -

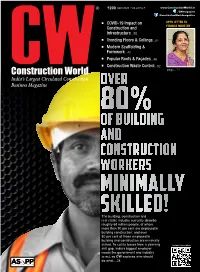

Over of Building and Construction Workers

`200 April 2020 • Vol.22 No.7 www.ConstructionWorld.in /CWmagazine /ConstructionWorldmagazine COVID-19 Impact on OPEN LETTER TO Construction and FINANCE MINISTER Infrastructure...38 Trending Floors & Ceilings...64 Modern Scaffolding & Formwork...40 Popular Roofs & Façades...46 Construction Waste Control...52 page...14 Over 80% of building and construction workers minimally skilled! The building, construction and real estate industry currently absorbs roughly 68 million people, of whom more than 90 per cent are deployed in building construction; and over 80 per cent of those employed in building and construction are minimally skilled. To cut its losses from a yawning Instant Subscription skill gap, India’s biggest employer needs the government and industry to act, as CW explores who should do what....28 SmartCitiesCouncil India LIVABILITY WORKABILITY SUSTAINABILITY JOIN WORLD-CLASS COMPANIES HELP CITIES BECOME MORE SUSTAINABLE WHAT the Council does... Smart Cities Council works with city leaders & officials across the country to make their cities more livable, workable and sustainable We give cities trusted, vendor-neutral guidance and best practices from the country’s leading experts. It provides Awareness, Advocacy, and Action. The Council gets cities ready to adopt smart technologies and connects them with our partners, who are leading stakeholders in the ecosystem Website: India.SmartCitiesCouncil.com FEW OF OUR PARTNERS TO KNOW MORE CONTACT: Tanveer Padode | Manager - Operations | Tel: 022 24175738 | Mob: +91 9324579821 | Emaill: [email protected] RESPOND (5T307) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN (05761) + RESPOND COLOR (5T310) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN LAKE (05327) | INSTALLED BRICK RESPOND (5T307) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN (05761) + RESPOND COLOR (5T310) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN LAKE (05327) | INSTALLED BRICK RESPOND (5T307) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN (05761) + RESPOND COLOR (5T310) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN LAKE (05327) | INSTALLED BRICK Step into a space designed to engage, evolve and revitalize the senses. -

WHAT USE IS MUSIC in an OCEAN of SOUND? Towards an Object-Orientated Arts Practice

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR WHAT USE IS MUSIC IN AN OCEAN OF SOUND? Towards an object-orientated arts practice AUSTIN SHERLAW-JOHNSON OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY Submitted for PhD DECEMBER 2016 Contents Declaration 5 Abstract 7 Preface 9 1 Running South in as Straight a Line as Possible 12 2.1 Running is Better than Walking 18 2.2 What You See Is What You Get 22 3 Filling (and Emptying) Musical Spaces 28 4.1 On the Superficial Reading of Art Objects 36 4.2 Exhibiting Boxes 40 5 Making Sounds Happen is More Important than Careful Listening 48 6.1 Little or No Input 59 6.2 What Use is Art if it is No Different from Life? 63 7 A Short Ride in a Fast Machine 72 Conclusion 79 Chronological List of Selected Works 82 Bibliography 84 Picture Credits 91 Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for any other award and that it is all my own work. Name: Austin Sherlaw-Johnson Signature: Date: 23/01/18 Abstract What Use is Music in an Ocean of Sound? is a reflective statement upon a body of artistic work created over approximately five years. This work, which I will refer to as "object- orientated", was specifically carried out to find out how I might fill artistic spaces with art objects that do not rely upon expanded notions of art or music nor upon explanations as to their meaning undertaken after the fact of the moment of encounter with them. -

Onwisconsin Summer 2014

For University of Wisconsin-Madison Alumni and Friends Drawn In Professor Jordan Ellenberg loves math — and says that you should, too. 24 Summer 2014 The Harmony of Numbers 28 | Doctors for the Forgotten 32 | Bye Bye Birdies 36 | When DNA is TMI 46 YOUR YOUR PRESENT. LEGACY. OUR FUTURE. GIFTS CAN MULTI-TASK. By establishing a charitable gift THEIR annuity at the University of Wisconsin Foundation, you • invest in the future of the UW-Madison • receive income for life FUTURE. • generate tax benefits We can shape how we’re remembered. Remembering the University of Wisconsin-Madison in your will is an investment in the future. For our children. For our university. For the world. To discuss your legacy, contact Scott McKinney in the Offi ce of Gift Planning at the University of Wisconsin Foundation at [email protected] or 608-262-6241. supportuw.org/gift-planning UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN FOUNDATION For more information, contact Scott McKinney in the Office of Gift Planning at [email protected] or 608-262-6241. On Wisconsin Full Pg October 2012.indd 1 10/10/2012 11:00:28 AM NOW OPEN to all University of Wisconsin-Madison alumni Overnight accommodations at the Fluno Center offer a welcome retreat after a long day of meetings, a convenient place to stay after a Badger game, or STAY IN THE simply a luxurious night in the heart of campus. Enjoy spectacular views of Madison while you HEART OF CAMPUS relax in style. The Fluno Center: Steps Away. A Notch Above. Visit fluno.com for more information. -

The Field Guide to Sponsored Films

THE FIELD GUIDE TO SPONSORED FILMS by Rick Prelinger National Film Preservation Foundation San Francisco, California Rick Prelinger is the founder of the Prelinger Archives, a collection of 51,000 advertising, educational, industrial, and amateur films that was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2002. He has partnered with the Internet Archive (www.archive.org) to make 2,000 films from his collection available online and worked with the Voyager Company to produce 14 laser discs and CD-ROMs of films drawn from his collection, including Ephemeral Films, the series Our Secret Century, and Call It Home: The House That Private Enterprise Built. In 2004, Rick and Megan Shaw Prelinger established the Prelinger Library in San Francisco. National Film Preservation Foundation 870 Market Street, Suite 1113 San Francisco, CA 94102 © 2006 by the National Film Preservation Foundation Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prelinger, Rick, 1953– The field guide to sponsored films / Rick Prelinger. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-9747099-3-X (alk. paper) 1. Industrial films—Catalogs. 2. Business—Film catalogs. 3. Motion pictures in adver- tising. 4. Business in motion pictures. I. Title. HF1007.P863 2006 011´.372—dc22 2006029038 CIP This publication was made possible through a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. It may be downloaded as a PDF file from the National Film Preservation Foundation Web site: www.filmpreservation.org. Photo credits Cover and title page (from left): Admiral Cigarette (1897), courtesy of Library of Congress; Now You’re Talking (1927), courtesy of Library of Congress; Highlights and Shadows (1938), courtesy of George Eastman House.