Inside the White Cube: the Ideology of the Gallery Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anya Gallaccio

ANYA GALLACCIO Born Paisley, Scotland 1963 Lives London, United Kingdom EDUCATION 1985 Kingston Polytechnic, London, United Kingdom 1988 Goldsmiths' College, University of London, London, United Kingdom SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 NOW, The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, Scotland Stroke, Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA 2018 dreamed about the flowers that hide from the light, Lindisfarne Castle, Northumberland, United Kingdom All the rest is silence, John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, United Kingdom 2017 Beautiful Minds, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2015 Silas Marder Gallery, Bridgehampton, NY Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, San Diego, CA 2014 Aldeburgh Music, Snape Maltings, Saxmundham, Suffolk, United Kingdom Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA 2013 ArtPace, San Antonio, TX 2011 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom Annet Gelink, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2010 Unknown Exhibition, The Eastshire Museums in Scotland, Kilmarnock, United Kingdom Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2009 So Blue Coat, Liverpool, United Kingdom 2008 Camden Art Centre, London, United Kingdom 2007 Three Sheets to the wind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2006 Galeria Leme, São Paulo, Brazil One art, Sculpture Center, New York, NY 2005 The Look of Things, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA Silver Seed, Mount Stuart Trust, Isle of Bute, Scotland 2004 Love is Only a Feeling, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY 2003 Love is only a feeling, Turner Prize Exhibition, -

The Art of Hans Arp After 1945

Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 Volume 2 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers Volume 2 The Art of Arp after 1945 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Table of Contents 10 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning 12 Foreword Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger 16 The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 An Introduction Maike Steinkamp 25 At the Threshold of a New Sculpture On the Development of Arp’s Sculptural Principles in the Threshold Sculptures Jan Giebel 41 On Forest Wheels and Forest Giants A Series of Sculptures by Hans Arp 1961 – 1964 Simona Martinoli 60 People are like Flies Hans Arp, Camille Bryen, and Abhumanism Isabelle Ewig 80 “Cher Maître” Lygia Clark and Hans Arp’s Concept of Concrete Art Heloisa Espada 88 Organic Form, Hapticity and Space as a Primary Being The Polish Neo-Avant-Garde and Hans Arp Marta Smolińska 108 Arp’s Mysticism Rudolf Suter 125 Arp’s “Moods” from Dada to Experimental Poetry The Late Poetry in Dialogue with the New Avant-Gardes Agathe Mareuge 139 Families of Mind — Families of Forms Hans Arp, Alvar Aalto, and a Case of Artistic Influence Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen 157 Movement — Space Arp & Architecture Dick van Gameren 174 Contributors 178 Photo Credits 9 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning Hans Arp’s late work after 1945 can only be understood in the context of the horrific three decades that preceded it. The First World War, the catastro- phe of the century, and the Second World War that followed shortly thereaf- ter, were finally over. -

Bortolami Gallery Through June 15Th, 2019.” Art Observed, May 30Th, 2019, Illus

BORTOLAMI Virginia Overton (b. 1971 in Nashville, Tennessee) Lives and works in Brooklyn, New York Education 2005 University of Memphis, TN, MFA 2002 University of Memphis, TN, BFA Solo Exhibitions 2019 Água Viva, Bortolami, New York, NY Francesca Pia, Zürich, Switzerland (forthcoming) 2018 Built, Don River Valley Park, Toronto, Canada secret space, Biel, Switzerland Built, Socrates Sculpture Park, Queens, NY Virginia Overton, University of Memphis Fogelman Galleries, Memphis, TN 2017 Why?! Why Did You Take My Log?!?!, Museum of Contemporary Art, Tucson, AZ 2016 Winter Garden, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY White Cube Bermondsey, London, England Sculpture Gardens, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT 2015 White Cube, London, England 2014 Flat Rock, Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami, North Miami, FL 2013 Westfälischer Kunstverein, Munster, Germany Kunsthalle Bern, Bern, Switzerland Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, NY 2012 The Kitchen, New York, NY Deluxe, The Power Station, Dallas, TX 2011 Freymond-Guth, Zürich, Switzerland 2010 Untitled (Milano), N.O. Gallery, Milan, Italy Cheekwood Museum of Art, Nashville, TN True Grit, Dispatch, New York, NY 2008 Moving on South, curated by Dana Orland, White Box, New York, NY This Is Not A Ladder, Artlab at AMUM, Memphis, TN 39 WALKER STREET NEW YORK NY 10013 T 212 727 2050 BORTOLAMIGALLERY.COM BORTOLAMI 2007 Skytracker, Powerhouse, Memphis, TN Selected Group Exhibitions 2019 Downtown Painting, curated by Alex Katz, Peter -

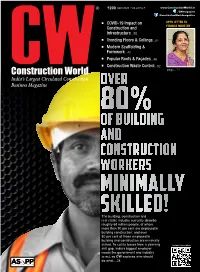

Over of Building and Construction Workers

`200 April 2020 • Vol.22 No.7 www.ConstructionWorld.in /CWmagazine /ConstructionWorldmagazine COVID-19 Impact on OPEN LETTER TO Construction and FINANCE MINISTER Infrastructure...38 Trending Floors & Ceilings...64 Modern Scaffolding & Formwork...40 Popular Roofs & Façades...46 Construction Waste Control...52 page...14 Over 80% of building and construction workers minimally skilled! The building, construction and real estate industry currently absorbs roughly 68 million people, of whom more than 90 per cent are deployed in building construction; and over 80 per cent of those employed in building and construction are minimally skilled. To cut its losses from a yawning Instant Subscription skill gap, India’s biggest employer needs the government and industry to act, as CW explores who should do what....28 SmartCitiesCouncil India LIVABILITY WORKABILITY SUSTAINABILITY JOIN WORLD-CLASS COMPANIES HELP CITIES BECOME MORE SUSTAINABLE WHAT the Council does... Smart Cities Council works with city leaders & officials across the country to make their cities more livable, workable and sustainable We give cities trusted, vendor-neutral guidance and best practices from the country’s leading experts. It provides Awareness, Advocacy, and Action. The Council gets cities ready to adopt smart technologies and connects them with our partners, who are leading stakeholders in the ecosystem Website: India.SmartCitiesCouncil.com FEW OF OUR PARTNERS TO KNOW MORE CONTACT: Tanveer Padode | Manager - Operations | Tel: 022 24175738 | Mob: +91 9324579821 | Emaill: [email protected] RESPOND (5T307) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN (05761) + RESPOND COLOR (5T310) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN LAKE (05327) | INSTALLED BRICK RESPOND (5T307) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN (05761) + RESPOND COLOR (5T310) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN LAKE (05327) | INSTALLED BRICK RESPOND (5T307) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN (05761) + RESPOND COLOR (5T310) IN COLOR MOUNTAIN LAKE (05327) | INSTALLED BRICK Step into a space designed to engage, evolve and revitalize the senses. -

Richard Wentworth Samoa, 1947 Vive Y Trabaja En Londres, UK

CV Richard Wentworth Samoa, 1947 Vive y trabaja en Londres, UK Educación 2009/11 Profesor de escultura, Royal College of Art, Londres, UK 2002/10 Ruskin Master of Drawing, Ruskin School of Art, Oxford, UK 2001 Beca en San Francisco School of Art, San Francisco, CA, USA 1971/87 Tutor, Goldsmith's College, University of London, Londres, UK 1967 Trabajó para Henry Moore, UK 1966/70 Royal College of Art, London, UK Exposiciones individuales (selección) 2020 There’s no knowing, Blind Alley projects, Fort Worth, Texas, US 2019 Lecciones Aprendidas, NoguerasBlanchard, Madrid, ES School Prints 2019, The Hepworth Wakefield, UK 2017 Concertina, Arebyte Gallery, Londres, UK Richard Wentworth at Maison Alaïa, Galerie Azzedine Alaïa, París, FR Richard Wentworth: Paying A Visit, Nogueras Blanchard, Barcelona, ES Now and Then, Peter Freeman Inc., New York, USA 2015 False Ceiling, Museo de arte de Indianápolis, USA Bold Tendencies, Peckham, Londres, UK 2014 Motes to self, Peter Freeman Inc., New York, NY, USA 2013 A room full of lovers, Lisson Gallery, Londres, UK Black Maria (en colaboración con Gruppe), Kings Cross, Londres, UK 2012 Galeria Nicoletta Rusconi (con Alessandra Spranzi), Milán, IT Galerie Nelson Freeman, Art 43 Basel, Basel, CHE 2011 Richard Wentworth, Galerie Nelson Freeman, París, FR Richard Wentworth, Peter Freeman Inc., París, FR Richard Wentworth: Sidelines, Museu da Farmacia, Experimenta Design, Lisboa, PT 2010 Three Guesses, Whitechapel Gallery, Londres, UK Richard Wentworth, Peter Freeman Inc., New York, NY, USA 2009 Scrape/Scratch/Dig, -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Quinn Biography

MARC QUINN BIOGRAPHY Born in London, England, 1964. Education: Cambridge University, Cambridge, England, 1985. Lives in London, England. Selected Solo Shows: 1988 “Bronze Sculpture”, Jay Jopling/Otis Gallery, London, England. 1990 “Bread Sculpture”, Galerie Nikki Diana Marquardt, Paris, France. 1991 “Out of Time”, Grob Gallery, London, England. “Out of Time”, Jay Jopling, London, England. 1993 Galerie Jean Bernier, Athens, Greece. 1995 “Art Now. Emotional Detox: The Seven Deadly Sins”, The Tate Gallery of Modern Art, London, England. “Blind Leading the Blind”, Jay Jopling/White Cube, London, England. 1998 South London Gallery, London, England. “Marc Quinn – Incarnate”, Gagosian Gallery, NYC, NY. 1999 Kunstverein Hannover, Hannover, Germany. 2000 Fondazione Prada, Milan, Italy. Groninger Museum, Groningen, The Netherlands. “Still Life”, White Cube², London, England. 2001 “Italian Landscape”, Habitat, London, England. “Marc Quinn: Garden”, Art of This Century, Paris, France. “A Genomic Portrait: Sir John Sulston by Marc Quinn”, National Portrait Gallery, London, England. 2002 “Italian Landscapes from Garden 2000”, Terrace Gallery, Harewood House, Leeds, England. Tate Liverpool, Liverpool, England. 2003 “The Overwhelming World of Desire (Paphiopedilum Winston Churchill Hybrid)”, Goodwood Sculpture Park, Chichester, West Sussex, England. “The Overwhelming World of Desire (Phragmipedium Sedenii)”, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, Italy. 2004 “The Complete Marbles”, Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. “Flesh”, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland. MARC QUINN BIOGRAPHY (continued) : Selected Solo Shows: 2005 “Flesh”, Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. “Chemical Life Support”, White Cube, London, England. “Alison Lapper Pregnant”, Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square, London, England. 2006 “Marc Quinn: Recent Sculptures”, Groninger Museum, Groningen, The Netherlands. Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Roma, Rome, Italy. 2007 “Sphinx”, Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. -

You Cannot Be Serious: the Conceptual Innovator As Trickster

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art Volume Author/Editor: David W. Galenson Volume Publisher: Cambridge University Press Volume ISBN: 978-0-521-11232-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gale08-1 Publication Date: October 2009 Title: You Cannot be Serious: The Conceptual Innovator as Trickster Author: David W. Galenson URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5791 Chapter 8: You Cannot be Serious: The Conceptual Innovator as Trickster The Accusation The artist does not say today, “Come and see faultless work,” but “Come and see sincere work.” Edouard Manet, 18671 When Edouard Manet exhibited Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe at the Salon des Refusés in 1863, the critic Louis Etienne described the painting as an “unbecoming rebus,” and denounced it as “a young man’s practical joke, a shameful open sore not worth exhibiting this way.”2 Two years later, when Manet’s Olympia was shown at the Salon, the critic Félix Jahyer wrote that the painting was indecent, and declared that “I cannot take this painter’s intentions seriously.” The critic Ernest Fillonneau claimed this reaction was a common one, for “an epidemic of crazy laughter prevails... in front of the canvases by Manet.” Another critic, Jules Clarétie, described Manet’s two paintings at the Salon as “challenges hurled at the public, mockeries or parodies, how can one tell?”3 In his review of the Salon, the critic Théophile Gautier concluded his condemnation of Manet’s paintings by remarking that “Here there is nothing, we are sorry to say, but the desire to attract attention at any price.”4 The most decisive rejection of these charges against Manet was made in a series of articles published in 1866-67 by the young critic and writer Emile Zola. -

NMMS Staff Kick Off New School BRISTOL — a Group Said

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2017 FREE IN PRINT, FREE ON-LINE • WWW.NEWFOUNDLANDING.COM COMPLIMENTARY Public hearing set on Town Hall project BY THOMAS P. CALDWELL hearing. A work session the existing municipal a new town hall on prop- sion. police station,” Solomon Contributing Writer on Sept. 29 will focus on building to serve only erty next door which the “We want to create a said, explaining that the BRISTOL — Samyn- putting cost figures with the Bristol Police De- town had purchased for new center with an invit- driveway would go be- D’Elia Architects of Ash- the conceptual floor partment and building possible future expan- ing front entrance to the SEE TOWN HALL, PAGE A14 land, hired last May to plans, in preparation for create preliminary plans the hearing. for a solution to the space Duncan, who had of- needs of the Bristol Mu- fered the amendment at nicipal Building, will the 2016 Town Meeting offer some drawings for that set the process in public review at the Old motion, and served on Town Hall on Wednes- the space needs commit- day, Aug. 4, at 7 p.m. tee when it came up with Architect Cris Solo- the recommendation mon joined space needs for two buildings, said committee member Su- the committee reviewed san Duncan in giving the options again with the Bristol Board of Se- Samyn-D’Elia to see if lectmen an advance look they could meet all the at the drawings on Sept. needs with renovations 21, noting that the de- to the existing building. sign work is still in prog- Solomon said they are ress and the plans could still recommending two change before the public buildings, converting Newfound parents COURTESY — CHRIS DYER renew push for Rainbow over Newfound Chris Dyer of Bristol spotted a full rainbow over Newfound Lake last week, and captured this beautiful scene with his camera. -

EILEEN QUINLAN Eileen Quinlan Is Interested in the False Transparency of the Photographic Image: It's Not a Window, but a Mirror

MIGUEL ABREU GALLERY EILEEN QUINLAN Eileen Quinlan is interested in the false transparency of the photographic image: it's not a window, but a mirror. Her work presents an opportunity for contemplation alongside an alienation effect that interrupts it—an awareness of the mechanics of presenting and consuming images, or a sudden bracing encounter with the clumsy hand of the artist, attempting to adjust the veil. Color, atmosphere, composition, and description are reduced to their most basic forms, taking turns as the central subject of the photographs. Quinlan’s process of experimentation with a limited set of materials is elaborated through brute repetition, demystifying the circumstances of each image’s creation. It insists, by extension, on the constructed nature of all photographs. The constructions themselves run the photographic gamut from the quasi-pictorial to the semi-abstract, from evidentiary document to expressive collage. The hand of the artist is both absent and frustratingly present. Ghosts of art history materialize, though dismembered, only to recede again. Quinlan’s early series, such as Smoke & Mirrors and Night Flight, restage display materials—mirrors, lights, textiles, and support structures—in disorienting configurations that verge on abstraction. Produced using the most common tricks of the commercial photography trade, the sets are staged around a nonexistent product; they are straightforward tabletop still-lives, manipulated neither in the darkroom nor through digital craft, though they often appear otherwise. More recently, the artist has taken yoga mats, luridly lit and shot in close-up, as the subject of a series that gestures toward contemporary manifestations of self-maintenance through regimes of diet, exercise, and spirituality. -

A Collection of Poems and Songs) Del Vaugh Schmidt Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1989 Waitin' for the blow (a collection of poems and songs) Del Vaugh Schmidt Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Vaugh Schmidt, Del, "Waitin' for the blow (a collection of poems and songs)" (1989). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 204. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/204 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -------- Waitin' for the blow (A collection of poems and songs) by Del Vaughn Schmidt A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: English (Creative Writing) Approved: Signature redacted for privacy //"' Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy For College Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1989 ----------- ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE iv POEMS 1 Feeding the Horses 2 The Barnyard 3 Colorado, Summer 1979 5 Arrival 8 Aliens 10 Communicating 12 Home 13 Jeff 15 Waitin' for the Blow 17 Real Surreal 21 Stove Wall 22 Positive 25 Playin' 26 Maybe it's the Music 27 SONGS 31 Have Another (for Colorado) 32 Wake Up 34 Unemployment Blues 36 Players 37 Train We're On 38 Institution 40 iii Farmer's Lament 42 Space Blues 44 You Would Have Made the Day 45 Four Nights in a Row 47 Helpless Bound 49 Carpenter's Blues 50 Hills 51 iv PREFACE Up to the actual point of writing this preface, I have never given much deep thought as to the difference between writing song lyrics and poetry. -

Nothing Happened

NOTHING HAPPENED A History Susan A. Crane !"#$%&'( )$*+,'-*". /',-- Stanford, California !"#$%&'( )$*+,'-*". /',-- Stanford, California ©2020 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Crane, Susan A., author. Title: Nothing happened : a history / Susan A. Crane. Description: Stanford, California : Stanford University Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020013808 (print) | LCCN 2020013809 (ebook) | ISBN 9781503613478 (cloth) | ISBN 9781503614055 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: History—Philosophy. | Collective memory. Classification: LCC D16.9 .C73 2020 (print) | LCC D16.9 (ebook) | DDC 901—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020013808 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020013809 Cover design: Rob Ehle Cover photos: Historical marker altered from photo (Brian Stansbury) of a plaque commemorating the Trail of Tears, Monteagle, TN, superimposed on photo of a country road (Paul Berzinn). Both via Wikimedia Commons. Text design: Kevin Barrett Kane Typeset at Stanford University Press in 11/15 Mercury Text G1 A mind lively and at ease can do with seeing nothing, and can see nothing that does not answer. J#$, A0-",$, E MMA CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Episodes in a History of Nothing 1 EPISODE 1 Studying How Nothing Happens 21 EPISODE 2 Nothing Is the Way It Was 67 EPISODE 3 Nothing Happened 143 CONCLUSION There Is Nothing Left to Say 217 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks for Nothing 223 Notes! 227 Index 239 NOTHING HAPPENED Introduction EPISODES IN A HISTORY OF NOTHING !"#$# %&'()"**# +'( ,#**-.