Marxism in Bulgaria Before 1891

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 a New Political Dawn: the Cuban Revolution in the 1960S

Notes 1 A New Political Dawn: The Cuban Revolution in the 1960s 1. For an outline of the events surrounding the Padilla Affair, see chapter two. 2. Kenner and Petras limited themselves to mentioning the enormous importance of a Cuban Revolution with which a great number of the North American New Left identified. They also dedicated their book to the Cuban and Vietnamese people for “giving North Americans the possibility of making a revolution” (1972: 5). 3. For an explanation of the term gauchiste and of its relevance to the New Left, see chapter six. 4. However, this consideration has been rather critical in the case of Minogue (1970). 5. The general consensus seems to be that, as the Revolution entered a period of rapid Sovietization following the failure of the ten million ton sugar harvest of 1970, Western intellectuals, who until then had showed support, sought to distance themselves from the Revolution. The single incident that seemingly sparked this reaction, in particular from some French intellectuals, was the Padilla Affair. 6. Here a clear distinction must be made mainly between the Communist Party of the pre-Revolutionary period, the Partido Socialista Popular (Popular Socialist Party) and the 26 July Movement (MR26). The former had a legacy of Popular Frontism, collaboration with Batista in the post- War period and a general distrust of “middle class adventurers” as it referred to the leadership of MR26 until 1958 (Karol, 1971: 150). The latter, led by Castro, had a radical though incoherently articulated ideo- logical basis. The process of unification of revolutionary organizations carried out between 1961 and 1965 did not completely obliterate the individuality of these competing discourses and it was in their struggle for supremacy that the New Left’s contribution was made. -

A Critical and Comparative Analysis of Organisational Forms of Selected Marxist Parties, in Theory and in Practice, with Special Reference to the Last Half Century

Rahimi, M. (2009) A critical and comparative analysis of organisational forms of selected Marxist parties, in theory and in practice, with special reference to the last half century. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/688/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A critical and comparative analysis of organisational forms of selected Marxist parties, in theory and in practice, with special reference to the last half century Mohammad Rahimi, BA, MSc Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Centre for the Study of Socialist Theory and Movement Faculty of Law, Business and Social Science University of Glasgow September 2008 The diversity of the proletariat during the final two decades of the 20 th century reached a point where traditional socialist and communist parties could not represent all sections of the working class. Moreover, the development of social movements other than the working class after the 1960s further sidelined traditional parties. The anti-capitalist movements in the 1970s and 1980s were looking for new political formations. -

The Ideas of Marxism-Leninism Will Triumph on the Revisionism

THE IDEAS OF MARXISM-LENINISM WILL TRIUMPH ON THE REVISIONISM W9 mo «853 19 6 2 (5x mm THE IDEAS OF MARXISM-LENINISM WILL TRIUMPH ON THE REVISIONISM 1962 >0 I .. THE DECLARATION OF THE CENTRAL COMMITTEE OF THE PARTY OF LABOUR OF ALBANIA At the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union N. Khrushchev publically attacked the Party of Labour of Albania. N. Khrushchev’s anti-marxist slanders and attacks serve only the enemies of com¬ munism and of the People’s Republic of Albania — the various imperialists and Yugoslav revisionists. N. Khrush¬ chev, laying bare the disputes existing long since between the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Party of Labour of Albania openly in the face of the enemies, brutally violated the 1960 Moscow declaration which points out that the disputes arousing between the fraternal parties should be settled patiently, in the spirit of proletarian internationalism and on the basis of the principles of equality and consultations. Publically attacking the Party of Labour of Albania, N. Khrushchev effectively began the open attack on the unity of the international communist and workers’ move¬ ment, on the unity of the socialist camp. N. Khrushchev bears full responsibility for this anti-marxist act and for all the consequences following from it. The Party of Labour of Albania, guided by the in¬ terests of the unity of the world communist movement and the socialist camp, with great patience, ever since our disputes arose with the Soviet leadership, has striven to solve them in the correct marxist-leninist way, in the way outlined by the Moscow Declaration. -

Chapter 2 Political Ideology and the Historical Roots of Terrorism

Chapter 2 Political Ideology and the Historical Roots of Terrorism CHAPTER OVERVIEW Chapter 2 explores the political and social theory that motivates certain groups—from the genesis of revolutionary ideology and terror to contemporary hate crime and radical Islamic movements. We start with the historic left-wing ideologies of socialism from the end of the 19th century and trace ideological ties to more contemporary perspectives of revolution in South America and the Middle. The final part of this chapter focuses on the historical roots of terrorism in the Middle East, from early anti-colonial ideology and the mandate system developed at the end of World War I to the establishment of Israel and the beginning of the Palestinian Resistance movement. CHAPTER OBJECTIVES Describe the concept of political terrorism. Provide an overview of leftist terror cells, including Latin American and European groups. Discuss how colonialism and the mandate system set the stage for future conflict in the Middle East. Describe the secular “first wave” Palestinian terror groups. Provide insight into how the United States and its policies have impacted terrorist ideology in the Middle East. LECTURE OUTLINE Introduction The subject of “politics” often provokes intense emotion, generates passionate discussion, and can frequently create extreme resistance to considering another person’s point of view. Identifying with a particular political theory or ideology can also help reduce uncertainty, make a person feel more secure, and increase feelings of solidarity with others. As such, it’s easy to understand “how” terrorists can add to and indoctrinate their ranks, particularly during times of perceived societal upheaval. -

Overview of Marxism, Black Liberation, and Black Working-Class Organic Intellectuals

THE DEVELOPMENT OF WORKING-CLASS ORGANIC INTELLECTUALS IN THE CANADIAN BLACK LEFT TRADITION: HISTORICAL ROOTS AND CONTEMPORARY EXPRESSIONS, FUTURE DIRECTIONS by Christopher Harris A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto © Copyright by Chris Harris 2011 THE DEVELOPMENT OF WORKING-CLASS ORGANIC INTELLECTUALS IN THE CANADIAN BLACK LEFT TRADITION: HISTORICAL ROOTS AND CONTEMPORARY EXPRESSIONS, FUTURE DIRECTIONS “Doctor” of Education (2011) Christopher Harris Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education University of Toronto Abstract This thesis explores the revolutionary adult education learning dimensions in a Canadian Black anti-racist organization, which continues to be under-represented in the Canadian Adult Education literature on social movement learning. This case study draws on detailed reflection based on my own personal experience as a leader and member of the Black Action Defense Committee (BADC). The analysis demonstrates the limitations to the application of the Gramscian approach to radical adult education in the non-profit sector, I will refer to as the Non-Profit Industrial Complex (NPIC) drawing on recent research by INCITE Women of Colour! (2007). This study fills important gaps in the new fields of studies on the NPIC and its role in the cooptation of dissent, by offering the first Canadian study of a radical Black anti-racist organization currently experiencing this. This study fills an important gap in the social movement and adult education literature related to the legacy of Canadian Black Communism specifically on the Canadian left. -

Critical Companion to Contemporary Marxism

Critical Companion to Contemporary Marxism BIDET2_f1_i-xv.indd i 10/25/2007 8:05:05 PM Historical Materialism Book Series Editorial Board Paul Blackledge, Leeds – Sébastien Budgen, Paris Michael Krätke, Amsterdam – Stathis Kouvelakis, London – Marcel van der Linden, Amsterdam China Miéville, London – Paul Reynolds, Lancashire Peter Thomas, Amsterdam VOLUME 16 BIDET2_f1_i-xv.indd ii 10/25/2007 8:05:05 PM Critical Companion to Contemporary Marxism Edited by Jacques Bidet and Stathis Kouvelakis LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 BIDET2_f1_i-xv.indd iii 10/25/2007 8:05:05 PM This book is an English translation of Jacques Bidet and Eustache Kouvelakis, Dic- tionnaire Marx contemporain. C. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 2001. Ouvrage publié avec le concours du Ministère français chargé de la culture – Centre national du Livre. This book has been published with financial aid of CNL (Centre National du Livre), France. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Translations by Gregory Elliott. ISSN 1570-1522 ISBN 978 90 04 14598 6 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

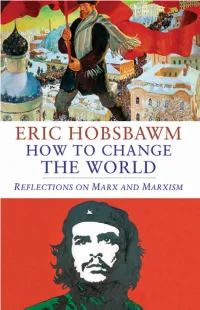

How to Change the World Also by Eric Hobsbawm

How to Change the World Also by Eric Hobsbawm The Age of Revolution 1789–1848 The Age of Capital 1848–1875 The Age of Empire 1875–1914 The Age of Extremes 1914–1991 Labouring Men Industry and Empire Bandits Revolutionaries Worlds of Labour Nations and Nationalism Since 1780 On History Uncommon People The New Century Globalisation, Democracy and Terrorism Interesting Times How to Change the World Reflections on Marx and Marxism Eric Hobsbawm New Haven & London To the memory of George Lichtheim This collection first published 2011 in the United States by Yale University Press and in Great Britain by Little, Brown. Copyright © 2011 by Eric Hobsbawm. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office). Typeset in Baskerville by M Rules. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2011927314 ISBN 978-0-300-17616-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Foreword vii PART I: MARX AND ENGELS 1 Marx Today 3 2 Marx, -

The Neo-Marxist Legacy in American Sociology

SO37CH08-Manza ARI 1 June 2011 11:32 The Neo-Marxist Legacy in American Sociology Jeff Manza and Michael A. McCarthy Department of Sociology, New York University, New York, NY 10012; email: [email protected], [email protected] Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011. 37:155–83 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on capitalism, class, political economy, state, work May 6, 2011 by New York University - Bobst Library on 08/08/12. For personal use only. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011.37:155-183. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org The Annual Review of Sociology is online at Abstract soc.annualreviews.org A significant group of sociologists entering graduate school in the late This article’s doi: 1960s and 1970s embraced Marxism as the foundation for a critical 10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150145 challenge to reigning orthodoxies in the discipline. In this review, we Copyright c 2011 by Annual Reviews. ask what impact this cohort of scholars and their students had on the All rights reserved mainstream of American sociology. More generally, how and in what 0360-0572/11/0811-0155$20.00 ways did the resurgence of neo-Marxist thought within the discipline lead to new theoretical and empirical research and findings? Using two models of Marxism as science as our guide, we examine the impact of sociological Marxism on research on the state, inequality, the labor process, and global political economy. We conclude with some thoughts about the future of sociological Marxism. 155 SO37CH08-Manza ARI 1 June 2011 11:32 INTRODUCTION (Burawoy & Wright 2002), not Marxist theory or politics outside the academy. -

Did Somebody Say Neoliberalism?: on the Uses and Limi- Tations of a Critical Concept in Media and Communication Studies Christian Garland* and Stephen Harper**

tripleC 10(2): 413-424, 2012 ISSN 1726-670X http://www.triple-c.at Did Somebody Say Neoliberalism?: On the Uses and Limi- tations of a Critical Concept in Media and Communication Studies Christian Garland* and Stephen Harper** * University of Warwick, UK and Fellow of Fellow of the Institut für Kritische Theorie, Freie Universität Berlin [email protected] ** University of Portsmouth, School of Creative Arts, Film and Media, Portsmouth, UK, [email protected] Abstract: This paper explores the political-economic basis and ideological effects of talk about neoliberalism with respect to media and communication studies. In response to the supposed ascendancy of the neoliberal order since the 1980s, many media and communication scholars have redirected their critical attentions from capitalism to neoliberalism. This paper tries to clarify the significance of the relatively new emphasis on neoliberalism in the discourse of media and com- munication studies, with particular reference to the 2011 phone hacking scandal at The News of the World. Questioning whether the discursive substitution of ‘neoliberalism’ for ‘capitalism’ offers any advances in critical purchase or explanatory power to critics of capitalist society and its media, the paper proposes that critics substitute a Marxist class analysis in place of the neoliberalism-versus-democracy framework that currently dominates in the field. Keywords: Neoliberalism, Marxism, Critical Theory, Critical Media and Communication Studies, Hackgate The media and communication studies textbooks of the early 1980s constituted an ideological battleground for the struggle between liberal pluralism, on the one hand, and Marxism, on the other (see, for example, Gurevitch et al. 1982). Under the influence of European critical theory and British cultural studies, Marxist communication scholars talked of capitalism and class strug- gle, and accused pluralists of underestimating structures of domination (Hall 1982). -

Christian and a Marxist at the Same Time—Not Without Irresolvable Contradictions

You Can Be A Christian, You Can Be A Marxist, But You Can’t Be Both Christians are being pressured into repeating the beliefs of a neo-Marxist, collective guilt ideology that’s incompatible with the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Joshua Lawson – The Federalist June 11, 2020 https://thefederalist.com/2020/06/11/you-can-be-christian-you-can-be-marxist-but-you-cant-be-both/ It’s unclear how many Christians are going along with the current neo- Marxist collective guilt movement out of fear, a misunderstanding of what they’ve signed onto, or an authentic conversion to the cause. What is clear, however, is that you can’t be a Christian and a Marxist at the same time—not without irresolvable contradictions. Whereas traditional garden-variety Marxism views history as a struggle between the wealthy and the working class “proletariat,” neo-Marxism cranks up the heat and redefines the fight to incorporate biological sex, race, ethnicity, and a whole gambit of various “identity” badges. The grand unifying principle for the Marxists behind the Black Lives Matter movement is that everything—and they mean everything—can be reduced to “oppressors” versus the “oppressed.” If you happen to be a member of one of the “oppressor” groups, then expect to see all sorts of punishments heading your way until the neo-Marxists are satisfied. Except they never are. Too many Christians are falling into a trap of expressing solidarity with an ideology that is completely antithetical to the teachings of Jesus. Right now, they need our prayers. Then, they need to wake up. -

1968: Memories and Legacies of a Global Revolt

Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Supplement 6 | 2009 1968: Memories and Legacies of a Global Revolt 5 Introduction: 1968 from Revolt to Research Philipp Gassert and Martin Klimke THE AMERICAS 27 Argentina: The Signs and Images of “Revolutionary War” Hugo Vezzetti 33 Bolivia: Che Guevara in Global History Carlos Soria-Galvarro 39 Canada: 1968 and the New Left Dimitri Roussopoulos 47 Colombia: The “Cataluña Movement” Santiago Castro-Gómez 51 Mexico: The Power of Memory Sergio Raúl Arroyo 57 Peru: The Beginning of a New World Oscar Ugarteche 63 USA: Unending 1968 Todd Gitlin 67 Venezuela: A Sociological Laboratory Félix Allueva ASIA & AUSTRALIA 73 Australia: A Nation of Lotus-Eaters Hugh Mackay 79 China: The Process of Decolonization in the Case of Hong Kong Oscar Ho Hing-kay 83 India: Outsiders in Two Worlds Kiran Nagarkar 89 Japan: “1968”—History of a Decade Claudia Derichs 95 Pakistan: The Year of Change Ghazi Salahuddin 99 Thailand: The “October Movement” and the Transformation to Democracy Kittisak Prokati AFRICA & THE MIDDLE EAST 105 Egypt: From Romanticism to Realism Ibrahim Farghali 111 Israel: 1968 and the “’67 Generation” Gilad Margalit 119 Lebanon: Of Things that Remain Unsaid Rachid al-Daif 125 Palestinian Territories: Discovering Freedom in a Refugee Camp Hassan Khadr 129 Senegal: May 1968, Africa’s Revolt Andy Stafford 137 South Africa: Where Were We Looking in 1968? John Daniel and Peter Vale 147 Syria: The Children of the Six-Day War Mouaffaq Nyrabia 2 1968: MEMORIES AND LEGACIES EASTERN EUROPE 155 Czechoslovakia: -

Politics of Marx As Non-Sectarian Revolutionary Class Politics: an Interpretation in the Context of the 20Th and 21St Centuries

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 8 2019 Politics of Marx as Non-sectarian Revolutionary Class Politics: An Interpretation in the Context of the 20th and 21st Centuries Raju Das York University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Das, Raju (2019) "Politics of Marx as Non-sectarian Revolutionary Class Politics: An Interpretation in the Context of the 20th and 21st Centuries," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.7.1.008319 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol7/iss1/8 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Politics of Marx as Non-sectarian Revolutionary Class Politics: An Interpretation in the Context of the 20th and 21st Centuries Abstract This article is condensed from three chapters of my Marxist Class Theory for a Skeptical World (Haymarket, 2018) and from a longer article based on these chapters. It is based on a talk on Marx’s politics’ delivered at ‘A Bicentenary Conference: Karl Marx at 200’ at Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario. Canada. I am thankful to the participants at this conference for their comments. Put simply, Marx’s politics is about class struggle for state power to build socialism, a society of popular democracy, by overthrowing capitalism.